Our student’s lives are filled with stressors. Students have the pressures of part- or full-time jobs, child and family care-taking responsibilities, financial difficulties, interpersonal relationship problems, and also mental and physical health issues. In fact, the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders is quite high, with 32% of adolescents meeting criteria for an anxiety disorder, and 14% meeting criteria for a mood disorder like depression (Merikangas et al., 2010; Watkins, Hunt, & Eisenberg, 2012).

Unfortunately, chronic anxiety and depression can reduce our ability to focus and learn new information. For professors, this should be of significant concern. Luckily, we are in a position to help our stressed students improve their learning while reducing the negative effects of stress on their lives. And by helping our students, we too can learn to better manage the effects of stress in our own lives.

Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) pedagogy offers several strategies that can help students better manage stress and reduce the negative physiological effects of stress on our brains and bodies.

Psychological distress & Learning

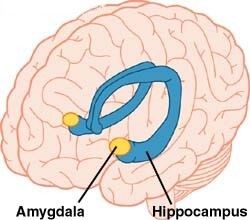

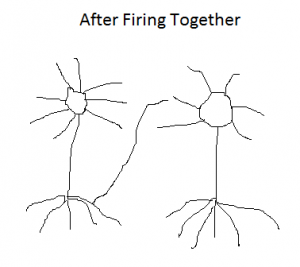

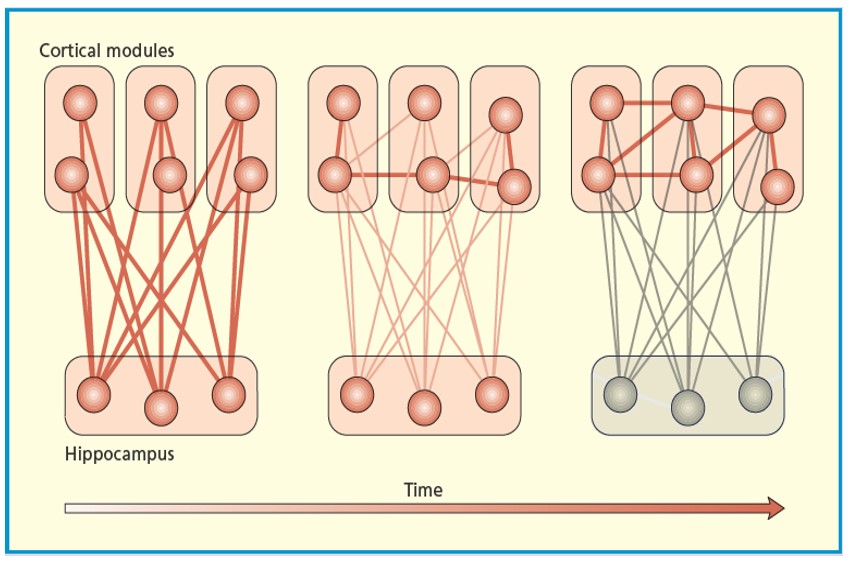

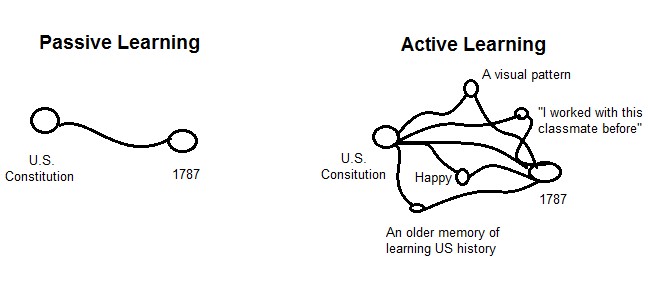

When a person is chronically stressed or depressed, their physiological stress systems that regulate physical well-being become altered (Grenham, Clarke, Cryan, & Dinan, 2011; Eskandari & Sternberg, 2002). In the brain, these changes are associated with damage to the hippocampus, a brain area that is very important for learning. We reviewed the importance of the hippocampus in learning in an earlier blog post, but in short, the presence of anxiety and depression can impact the size of our hippocampi (Bremner et al., 2000; Campbell, Marriott, Nahmias, & MacQueen, 2004) and thus reduces our ability to form new memories. Additionally, chronic psychological distress is also associated with altered attention and reduced cognitive performance (Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007).

What can professors do?

- We can teach our students profession-specific ways of dealing with psychological distress

We teach our students how to utilize information specific to their field, but isn’t it equally important that we help students manage the stress of these professions? There are a variety of ways that professionals practice self-care to remain effective, and we should be helping students develop these skills. You could even model this, by describing what self-care routines you follow yourself. Reviewing this can benefit the student as well as the teacher, as it may also make the professor more aware of the importance of self-care. Some ways that professionals manage stress include:

- Physical exercise. Physical movement is one of the most effective ways to reduce psychological distress. Research has even shown that regular exercise can be as effective as antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication. With many Americans and students sitting for much of the day, it is important to review how physical movement can be incorporated into one’s professional life. One effective way to encourage physical activity is to incorporate physical activities into the classroom.

- Meditation and/or mindfulness. This is an effective method to relax and focus, and is popular among psychologists, medical professionals, business people and athletes. Such techniques can be incorporated into classroom learning, even just by asking students to self-reflect and be aware of their current state. Low-stakes writing assignments may be especially helpful here.

- Gratitude. Practicing daily acts of gratitude can reduce stress and elevate mood. This could be tied to any field, but may be particularly useful to those in professions where they may encounter a significant amount of stress and sadness as part of their jobs.

- We Can Incorporate WAC Classroom Activities That Promote Stress Reduction

While reducing psychological distress is not necessarily an explicit goal of WAC pedagogy, many WAC strategies do fulfill this function. Below we discuss specific WAC strategies that may be particularly beneficial for anxious and depressed students:

- In-class writing exercises. Expressive writing is a powerful tool for reducing stress and depressive symptoms (Baikie & Wilhelm, 2005; Gortner, Rude, & Pennebaker, 2006). By making these low-stakes writing exercises specific to self-care topics, it could benefit the students further. Here are some examples:

- When introducing a large, scaffolded project to students, a professor could begin by having students’ free-write and reflect on their procrastination habits, what thoughts and feelings come up? How may they be able to manage these habits better for the upcoming project.

- When reviewing a midterm exam, you could ask students to free-write about their awareness of their stress. Ask them to reflect on the thoughts and feelings that come up as they review the exam material. Do they notice any physical reactions to stress? By having students identify their emotions, and bringing awareness to the impact of these emotions on their physical bodies, students can become more mindful of their emotional responses and be in the present moment.

- Self-criticism is highly prevalent amongst anxious and depressed students, and is often associated with perfectionism and procrastination. A free-write assignment could be included asking students to reflect on how they feel about themselves as students (do they feel like they’re good enough?), and asking them to imagine how their most compassionate selves would respond to their initial self-view. Such an exercise may be particularly helpful before exam grades are handed back.

- Scaffolded class assignments. One WAC strategy that helps fight procrastination is a scaffolded assignment design, a central practice of WAC pedagogy. Scaffolding means breaking down larger assignments into smaller tasks with due dates throughout the semester. Not only will you receive better developed class papers and projects, you will also assist your students in experiencing less anxiety and depression by reducing procrastination.

- Incorporating physical movement into class activities. Create activities that involve some level of movement. A great way to reduce the physiological effects of stress is through moving the body. A few activities could include:

- The Snowball activity: As a brainstorming session, have students answer a question on a piece of paper that they then crumple up and throw toward the front of the classroom. Students then have to get up and pick up a “snowball” in order to respond to the first students’ response.

- Creative Assignments: Send students to do assignments on campus or in the city that involve exploration. For example, for a history class, you could ask students to visit historical locations throughout the city. Students could be asked to film themselves at the site, explaining the location’s importance and relevance to other historical topics.

- Creating fun social in-class activities. One of the biggest antidotes against stress, anxiety and depression is social involvement. Laughter, feelings of happiness, and social connectedness reduce stress and cortisol levels. WAC pedagogy promotes group and peer activities, as this increases active learning. These social activities also have the added benefit of reducing stress and depression.

References

Anderson, G., & Horvath, J. (2004). The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public health reports, 119(3), 263.

Baikie, K. A., & Wilhelm, K. (2005). Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 11(5), 338-346.

Bremner, J. D., Narayan, M., Anderson, E. R., Staib, L. H., Miller, H. L., & Charney, D. S. (2000). Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression.American Journal of Psychiatry.

Campbell, S., Marriott, M., Nahmias, C., & MacQueen, G. M. (2004). Lower hippocampal volume in patients suffering from depression: a meta-analysis.American Journal of Psychiatry.

Eskandari, F., & Sternberg, E. M. (2002). Neural‐immune interactions in health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 966(1), 20-27.

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336

Gortner, E. M., Rude, S. S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behavior therapy, 37(3), 292-303.

Grenham, S., Clarke, G., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2011). Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Front Physiol, 2(94.10), 3389.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., … & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989.

Perrin, J. M., Bloom, S. R., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2007). The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. Jama, 297(24), 2755-2759.

Watkins, D. C., Hunt, J. B., & Eisenberg, D. (2012). Increased demand for mental health services on college campuses: Perspectives from administrators. Qualitative Social Work, 11(3), 319-337