A few days ago this 2014 article from the Washington Post came across my social media feed, and even though it’s about high school students, much of what the author writes is highly relevant to our students at City Tech as well. To summarize, this educational consultant spent a day shadowing two high school students and found that her experience going through the school day in their shoes had a significant impact on how she viewed her own pedagogy. In a kind of “if I knew then what I know now” moment, she mused on the things she would do differently in her teaching had she known what it was like to be a student.

Her two big takeaways that I find most relevant to college teaching are that 1) students spend much of their day sitting, and 2) students spend much of their class time passively listening to their teachers.

Of course, the first issue is not quite as big of an issue for college students. Unlike high schoolers, our students are not arriving by 8am every day, five days a week, and sitting in class after class into the mid-afternoon. Our students take maybe 3-5 classes depending on their schedules, and these are distributed across the week and throughout the day with longer breaks in between.

Still, our students likely spend much of their day sitting. Whether they’re in class, in the library, or sitting at a table in the atrium with friends or doing work, our students might not be moving around as much as we think. One way we can combat this is to build group work activities into our classes that require students to move around. The simple act of having our students move their desks a little to work in groups can help to break up the otherwise static mode of learning that our students experience just sitting in one place for 75 minutes.

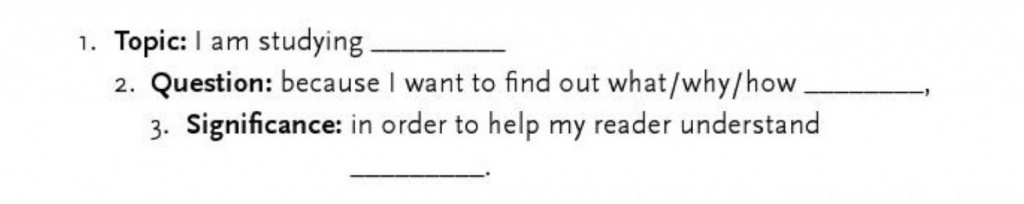

You can use group work to assist in writing activities such as brainstorming, thesis formation, or a close reading of an article. For example, when teaching students about choosing a topic for their papers, I like to give them a form borrowed from The Craft of Research (3rd ed., 2009) by Booth, Colomb, and Williams, which is available as an e-book to all CUNY users. The template is described on pages 46-48 of this edition, and presented with blanks on page 51:

I’ll begin by giving students a paper topic and have them fill this out, and then have them start to brainstorm their own topics in groups. To make sure that students are moving around, I will have everyone change seats halfway through, to re-arrange the groups. This can be done with many kinds of quick low-stakes writing exercises intended to get students brainstorming or generating some rough, general ideas or questions. Best of all, students leave the class with a number of viable topics that they can then start to craft into thesis statements.

The second issue the author of this Post article brought up is that students sit passively, and again, writing pedagogy can help us here. Try to incorporate at least one short writing assignment into every class. Many professors will start a class with a quick “free write” or other informal writing activity, but a great way to break up the passive learning is to have an informal writing activity in the middle of class. For example, if you are learning a new skill or topic, lecture about the example from the textbook, and then give students an example they haven’t seen before and a few direct and simple questions to answer in writing. A few minutes in the middle of class like this doesn’t take away from your time devoted to content either, rather, it enhances the understanding and knowledge retention of your students.