Last week we wrapped up the semester with a workshop on using non-traditional activities in the classroom to incorporate more active learning into our courses – and to have more fun! If you missed the workshop, read on to find out what we talked about, and check out the PowerPoint Slides and Handout.

WAC Fellow Emily Crandall and I started off with an active learning game that encourages student interaction: “The Snowball” (or, as WAC Coordinator Rebecca Devers likes to call it, “The Hungry Hungry Hippo” activity). Each person gets a piece of paper with a question at the top – here, “What is one concern you have about incorporating non-traditional (i.e. not lecture/discussion) activities into your classroom?” After writing down a response, each person crumples up the paper and throws it to the front of the room, which just about guarantees some looks of amazement and some hilarity when people’s aim goes astray. After collecting and redistributing the papers, each person opens up the one they’ve been given and some are read aloud. Then each person writes a response to the concern expressed on their paper. The papers are crumpled, thrown, and redistributed again, and the answers are discussed. This activity is a great way to loosen students up and get them interacting, in addition to providing a way for them to raise questions anonymously, without feeling self-conscious.

I then talked about active learning, which is an idea underpinning not just the workshop, but the WAC philosophy as a whole. Active learning, which can be defined as “any instructional method that engages students in the learning process” (Prince 2004), is typically juxtaposed with more traditional passive absorption of information in a lecture format. Of course, we all lecture sometimes, but incorporating active learning has a lot of benefits for your students and for you as a professor. Research shows that students learn better when they engage in a variety of activities (listening, talking, writing, etc); what’s more, having fun actually increases attentiveness, which in turn makes higher-level learning and deeper connections more likely. As a professor, coming up with innovative and engaging student activities can improve your teaching portfolio or even result in a publication in a pedagogy journal.

Moving on to no-tech activities, we focused on small group activities. Most of us have used small groups at some point in our classrooms, but it’s easy for them to feel like a waste of time. We gave some examples of fun and productive small group activities (see the handout for details), and then Emily described ways to make them more effective. For example, it’s a good idea to require groups to generate a written product that they will have to present, so that group conversations stay on track. Ask students to persuade the class when they present those written products, rather than simply summarize. And research shows that groups of 5-6 produce the most conducive environment for interactive learning.

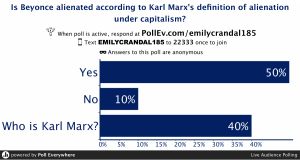

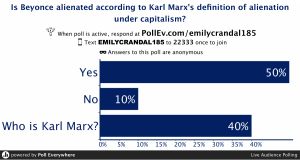

Using multimedia inside or outside the classroom also offer exciting ways to enliven lessons and promote more engaged learning. This can be as simple as showing a video clip and asking students to write for a few minutes in response before discussing those responses in class – a great way to incorporate low-stakes writing into the classroom. Or you can get a little fancier with only minimal extra effort, trying out some instant feedback techniques. Instant feedback can be used to gauge student comprehension, gather questions, provoke discussion, or even take attendance. We demonstrated an instant poll in the workshop using polleverywhere.com, a great resource that lets you set up a multiple-choice or free-response poll, have your students respond via cell phone or laptop, and display the results instantly as they come in. Our poll – based on a question WAC Fellow Wilson uses in her Intro to Sociology classes – started off with a strong lead for Beyonce’s alienation, but a late surge of “Who is Karl Marx?” responses made for a close finish.

Clickers, which some departments have (and if not, you can use technology fee money to help buy them), can be used for similar purposes, or you can even set up a hashtag for your class and have students tweet questions or responses for instant in-class feedback.

Finally, there are some great ways to use technology outside the classroom. OpenLab is a City Tech resource for setting up a course website, where you can post a dynamic course syllabus, run a class blog, or even create a multimedia class project, like this English/Communications class did. They even offer workshops to get you started; you can find schedules on their website.

Emily showed the workshop her own class blog (which is private, so no link here – but you can see another WAC Fellow’s class blog here as an example) and talked about the ways to use a blog and the benefits of doing so. It’s a great place to practice low-stakes writing; you can ask students to post once a week before class to ensure that they come to class prepared, but also to promote student interaction online. Requiring students to comment on each other’s posts – or offering extra credit for doing so – can generate discussions that you can continue in class. This is particularly useful for students who might feel intimidated or shy in class; it gives them a different way to participate, and it also can give them the confidence to then do so in the classroom after trying it out online. By asking students to post several hours before class, you can read their responses beforehand, which lets you identify and better address the concepts or issues students were most interested in or confused by.

The tasks you assign for blog posts could be the same each week, or you could change it up and use it as a scaffolding tool, according to course objectives. You could ask them to summarize and analyze of the week’s readings, identify a thesis or evidence, argue for or against the author’s position, connect the readings to personal experience, explain key concepts in plain English, or generate discussion questions. Be sure to give specific tasks for posting comments on other’s blog posts, too!

To wrap it up, Emily talked about a couple of ways to tie all of these ideas together. Of course, you certainly don’t have to incorporate everything into the same class, but if you’re wondering how you’re going to have time to use any of them, thinking about a flipped classroom model could be useful. In the flipped classroom, activities we typically do in class – primarily lecture – are done outside (via existing video content you find, such as TED talks or documentaries, or lectures you record of yourself), and activities typically done outside of class – the application of the lecture material – are done in class. So you essentially make room for in-class activities by shifting lectures out.

That’s it for this semester, but we’ll be back in the spring with several workshops for students, a faculty workshop on applying WAC principles with ESL students in the classroom, and a symposium in May to present all writing certification participants’ work from the year. Keep an eye out for the final schedule!