Contents [hide]

Non-Mendelian Genetics

Co-Dominance and multiple alleles

Co-dominance is said to occur when there is an expression of two dominant alleles. The prototypical case for this is the human ABO blood grouping.

Three alleles exist in the ABO system: A, B and O. This results in four blood types: A, B, O and the blended AB.

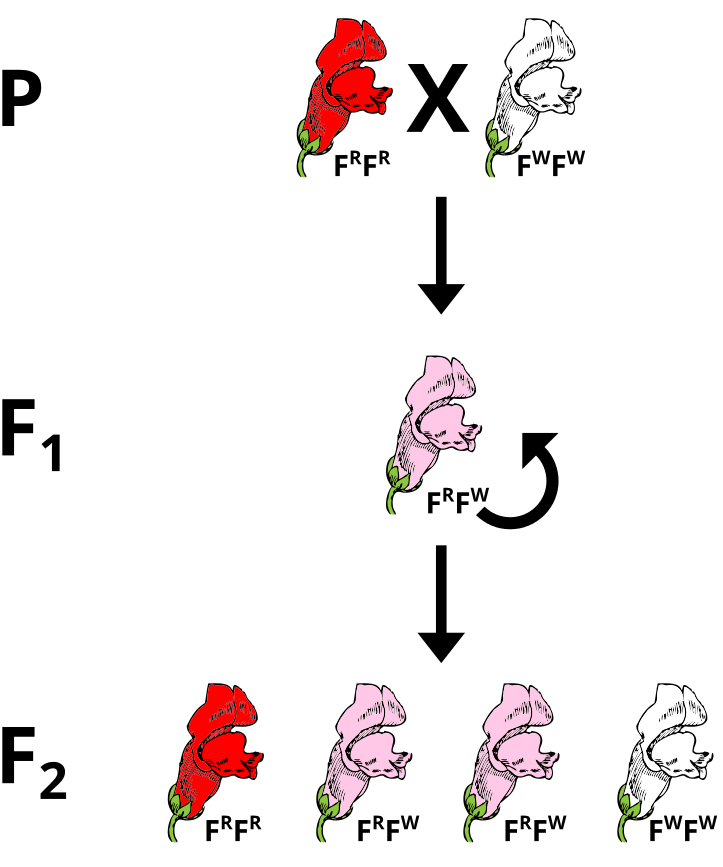

Incomplete Dominance

During Mendel’s time, people believed in a concept of blending inheritance whereby offspring demonstrated intermediate phenotypes between those of the parental generation. This was refuted by Mendel’s pea experiments that illustrated a Law of Dominance. Despite this, non-Mendelian inheritance can be observed in sex-linkage and co-dominance where the expected ratios of phenotypes are not observed clearly. Incomplete dominance superficially resembles the idea of blending inheritance, but can still be explained using Mendel’s laws with modification. In this case, alleles do not exert full dominance and the offspring resemble a mixture of the two phenotypes.

Problem: Incomplete Dominance

If pink flowers arose from blending inheritance, then subsequent crosses of pink flowers with either parental strain would continue to dilute the phenotype. Using a Punnet Square, perform a test cross between a heterozygous plant and a parental to predict the phenotypes of the offspring.

Epistasis and Modifier Genes

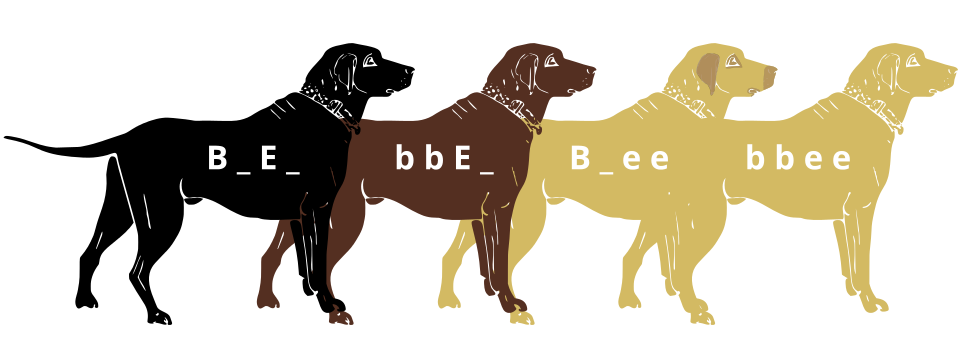

Genes do not exist in isolation and the gene products often interact in some way. Epistasis refers to the event where a gene at one locus is dependent on the expression of a gene at another genomic locus. Stated another way, one genetic locus acts as a modifier to another. This can be visualized easily in the case of labrador retriever coloration where three primary coat coloration schemes exist: black lab, chocolate lab and yellow lab.

Two genes are involved in the coloration of labradors. The first is a gene for a protein called TYRP1, which is localized to the melanosomes (pigment storing organelles). Three mutant alleles of this gene have been identified that reduce the function of the protein and yield lighter coloration. These three alleles can be noted as “b” while the functioning allele is called “B“. A heterozygous (Bb) or a homozygous dominant individual will be black coated while a homozygous recessive (bb) individual will be brown.

The second gene is tied to the gene for Melanocortin 1 Receptor (MC1R) and influences if the eumelanin pigment is expressed in the fur. This gene has the alleles denoted “E” or “e“. A yellow labrador will have a genotype of either Bbee or bbee.

Genetics of Migration

Genetic admixture refers to the mixture of identifiable markers hearkening to the parentage of organisms. These markers are not unique to individuals. Rather, they describe common features identifiable across various populations. They can not do this individually, but do so as combinations of these markers.

An example of understanding these concepts is to look at intentionally inbred (pure-breed) organisms that can be isolated as distinct breeds. Through studying genetic markers along the chromosomes, the ancestry of breeds can be identified. Java was a rescue dog from the south. He was roughly two years old and was clearly a mutt. In order to identify his ancestry, DNA was submitted to two genetic testing services. One provided a rough ancestry of percentages while, Embark offered thorough identification of genes and genetic markers that were associated with the ancestry and disease likelihood.

The breed analysis revealed that this mutt probably had a grandparent that was a rottweiler, another grandparent that was a doberman, another probable grandparent of Chinese ancestry (Shar-pei and Chow Chow), with the last grandparent being a mutt.

The Columbian Exchange and Admixture

- Norris, E.T., Wang, L., Conley, A.B. et al. Genetic ancestry, admixture and health determinants in Latin America. BMC Genomics 19 (Suppl 8), 861 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5195-7

- Rishishwar, L., Conley, A., Wigington, C. et al. Ancestry, admixture and fitness in Colombian genomes. Sci Rep 5, 12376 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12376

- Ruiz-Linares A, Adhikari K, Acuña-Alonzo V, Quinto-Sanchez M, Jaramillo C, et al. (2014) Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals. PLOS Genetics 10(9): e1004572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572

- Susan Fairley, Ernesto Lowy-Gallego, Emily Perry, Paul Flicek, The International Genome Sample Resource (IGSR) collection of open human genomic variation resources, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 48, Issue D1, 08 January 2020, Pages D941–D947, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz836

- Get Data from https://www.internationalgenome.org/home

Tags: integration of knowledge, cultural awareness