Contents

Meiosis: The Foundation of Genetic Variation

Homologous Chromosomes and Recombination:

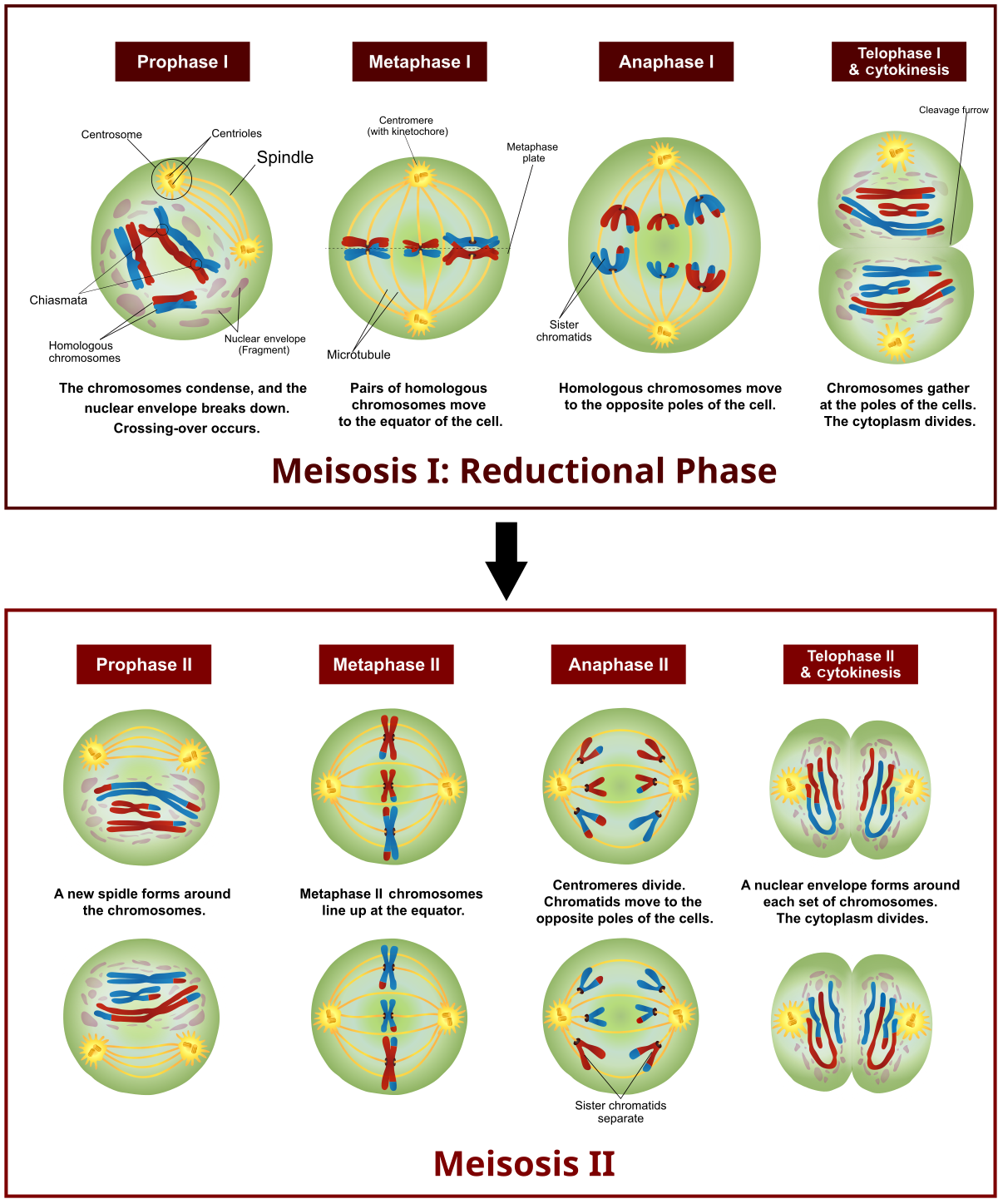

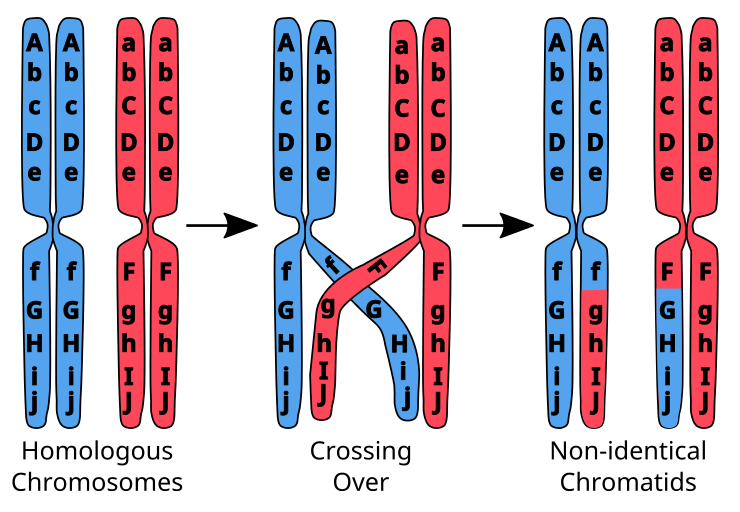

During the formation of egg and Sperm cells, the chromosomes are reduced in number in the process of meiosis. During this process, the chromosomes inherited from each parent line up in homologous pairs and sometimes touch each other in a process called synapsis. A crossing over event may occru in which portions of chromsomes are exchanged in order to enhance genetic diversity of the subsequent generation. At this point, the chromosomes consist of non-identical sister chromatids which will later separate in the second part of meiosis.

Genetic admixture refers to the mixture of identifiable markers hearkening to the parentage of organisms. These markers are not unique to individuals. Rather, they describe common features identifiable across various populations. They can not do this individually, but do so as combinations of these markers.

An example of understanding these concepts is to look at intentionally inbred (pure-breed) organisms that can be isolated as distinct breeds. Through studying genetic markers along the chromosomes, the ancestry of breeds can be identified. Java was a rescue dog from the south. He was roughly two years old and was clearly a mutt. In order to identify his ancestry, DNA was submitted to two genetic testing services. One provided a rough ancestry of percentages while, Embark offered thorough identification of genes and genetic markers that were associated with the ancestry and disease likelihood.

The breed analysis revealed that this mutt probably had a grandparent that was a rottweiler, another grandparent that was a doberman, another probable grandparent of Chinese ancestry (Shar-pei and Chow Chow), with the last grandparent being a mutt.

Migration and Gene Flow

Migration of Archaic Humans

Migration is the movement of individuals from one population to another.

Archaic humans like Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern humans reveal geographic isolation as well as interbreeding as described in the genetic register. Through whole genome sequencing of preserved specimens within the permafrost, direct hybrids have been identified. Contemporary genetic testing services provide insight into the percentage Neanderthal or Denisovan genes within ones genome. Geographical exclusions exist . For example, anyone of strictly sub-Saharan African background will have 0% contribution from Neanderthal or Denisovan.

Human migrations and development trace their way back to an African origin referred to as “Out of Africa”. As science continues to gather evidence, it becomes clear that this movement was not entirely unidirectional. Evidence shows that humans crossing into Asia and Europe did migrate back to northern Africa and back out.

Founder Effects and Genetic Bottlenecks

Since migrating groups represent a subset of the total population, an isolation and enrichment of certain alleles may occur. This founder effect may result in the loss of some genetic variation over a few generations.

Over time, the local landscape and other natural phenomena may shape the types of traits that are generally more favorable to the environment. Other natural events that drastically alter the size of the migrant population in those many generations may also result in genetic bottlenecks. These types of events reshape the frequency of genetic traits variants from the general population of the entire species. Over the course of many generations new variations may arise from these new settled sub-populations through natural mutations that occur in the genetic machinery.

Haplotypes

When utilizing a genetic testing service, it is likely that the initial information released is data corresponding to maternally inherited DNA through the mitochondrial genome before a thorough report is generated. Mitochondrial genomes are unique in that they are solely inherited from the mother’s line and they do not undergo recombination like the chromosomes. Because they lack a recombination mechanism, the rate of mutation in non-selected regions of the genome may also occur more rapidly. This yields our ability to distinguish maternal haplotypes that are geographically defined by prior founders and bottleneck events.

Using the mitochondrial genomic information, migration and spread of human lineages can be deciphered readily. The haplotype called L diverged into numerous lines. With this idealized Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA), the concept of a “Mitochondrial Eve” appears as the baseline group of maternal women who gave rise to modern humans.

The Effects of Imperial Expansion on Genetics and Admixture

Like the mitochondrial genome, the Y-chromosome is incapable of recombination. Since there are very few functional genes on the Y-chromosome, much of it is relaxed from selective pressures to maintain sequences free from mutations over the generations. This makes it ideal for haplotyping of males.

The great Mongol expansion through Asia started with the unification by Genghis Khan. With this expansion brought the interbreeding of Mongolians with indigenous populations and resulting in genetic admixture.

Through the interbreeding of Mongolians, it was estimated that a high percentage of males from central Asia had the Y-chromosome of Genghis Khan and his descendants from the Y Haplogroup C-M217.

Prior genetic evidence shows that many men within this region did have common Y-chromosomes, adding credence to the claims of the Khan ancestry. Despite this claim, it has been recently argued that the Y-chromosome haplogroup is descended of common Mongolians and not through direct descendants of Genghis Khan (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-017-0012-3) as evidenced in the Y-chromosomes found in native populations of North America. While the direct linkage does not hold true, the spread of Y chromosome C2*-Star Cluster demonstrates the longstanding effects of imperial expansion, interbreeding and subsequent forced migrations.

The Columbian Exchange and Admixture

- Norris, E.T., Wang, L., Conley, A.B. et al. Genetic ancestry, admixture and health determinants in Latin America. BMC Genomics 19 (Suppl 8), 861 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5195-7

- Rishishwar, L., Conley, A., Wigington, C. et al. Ancestry, admixture and fitness in Colombian genomes. Sci Rep 5, 12376 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12376

- Ruiz-Linares A, Adhikari K, Acuña-Alonzo V, Quinto-Sanchez M, Jaramillo C, et al. (2014) Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals. PLOS Genetics 10(9): e1004572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572

- Susan Fairley, Ernesto Lowy-Gallego, Emily Perry, Paul Flicek, The International Genome Sample Resource (IGSR) collection of open human genomic variation resources, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 48, Issue D1, 08 January 2020, Pages D941–D947, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz836

- Get Data from https://www.internationalgenome.org/home

Sally Hemings case study

Sally Hemings was slave owned by Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson had two legitimate daughters prior to his wife’s death. After his wife’s death it had been heavily implied that Sally Hemings gave rise to a number of illegitimate children. In 1998, a genetic study of males descended from Sally Hemings demonstrated that they possessed the Jeffersonian Y-chromosome. More information about Sally Hemings can be found on Monticello.org.

- Foster, E., Jobling, M., Taylor, P. et al. Jefferson fathered slave’s last child. Nature 396, 27–28 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1038/23835

Genetic Services and Ancestry DNA in the Context of Imperialism and Colonialism

- Rethinking Ancestry and Identity:

- Prompt: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/white-supremacists-respond-genetics-say-theyre-not-white

- Examine how genetic ancestry testing can challenge traditional notions of identity and belonging.

- Discuss the importance of considering cultural, social, and historical factors in understanding ancestry, especially in the context of colonialism and imperialism.

- Historical Context of Genetic Research:

- Discuss how genetic research has been influenced by historical events like colonialism and imperialism.

- Highlight the role of genetic studies in reinforcing racial stereotypes and justifying discriminatory practices.

- Ethical Considerations:

- Address ethical concerns related to the use of genetic data, particularly in marginalized communities that have experienced historical exploitation.

- Discuss the importance of informed consent and data privacy in genetic research.

- Decolonizing Genetics:

- Explore efforts to decolonize genetics by centering the voices and experiences of marginalized communities.

- Discuss the importance of collaborative research and equitable representation in genetic studies.