“Tell me,” Beloved said. “Tell me how Sethe made you in the boat.”

“She never told me all of it,” said Denver.

“Tell me.”

Denver climbed up on the bed and folded her arms under her apron. She had

not been in the tree room once since Beloved sat on their stump after the

carnival, and had not remembered that she hadn’t gone there until this very

desperate moment. Nothing was out there that this sister-girl did not provide

in abundance: a racing heart, dreaminess, society, danger, beauty. She

swallowed twice to prepare for the telling, to construct out of the strings she

had heard all her life a net to hold Beloved.

“She had good hands, she said. The whitegirl, she said, had thin little

arms but good hands. She saw that right away, she said. Hair enough for five

heads and good hands, she said. I guess the hands made her think she could do

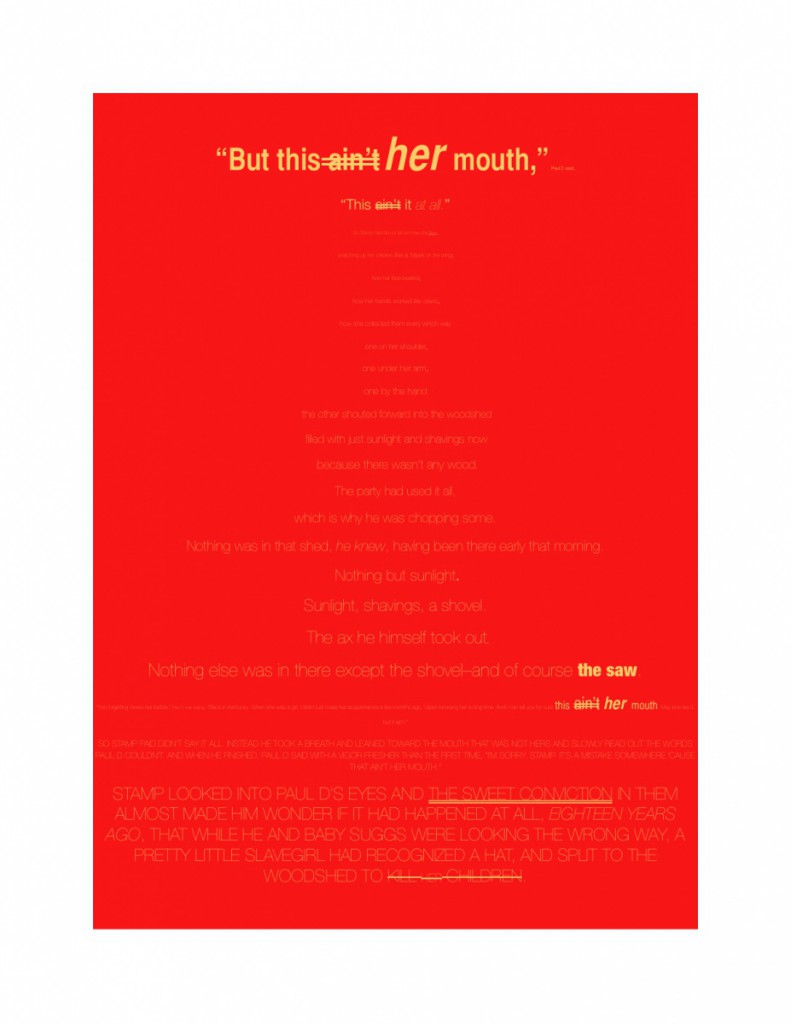

it: get us both across the river. But the mouth was what kept her from being

scared. She said there ain’t nothing to go by with whitepeople. You don’t know

how they’ll jump. Say one thing, do another. But if you looked at the mouth

sometimes you could tell by that. She said this girl talked a storm, but there

wasn’t no meanness around her mouth. She took Ma’am to that lean-to and rubbed

her feet for her, so that was one thing.

And Ma’am believed she wasn’t going to turn her over. You could get money

if you turned a runaway over, and she wasn’t sure this girl Amy didn’t need

money more than anything, especially since all she talked about was getting

hold of some velvet.”

“What’s velvet?”

“It’s a cloth, kind of deep and soft.”

“Go ahead.”

“Anyway, she rubbed Ma’am’s feet back to life, and she cried, she said,

from how it hurt. But it made her think she could make it on over to where

Grandma Baby Suggs was and…”

“Who is that?”

“I just said it. My grandmother.”

“Is that Sethe’s mother?”

“No. My father’s mother.”

“Go ahead.”

“That’s where the others was. My brothers and.., the baby girl.

She sent them on before to wait for her at Grandma Baby’s. So she had to

put up with everything to get there. And this here girl Amy helped.”

Denver stopped and sighed. This was the part of the story she loved. She

was coming to it now, and she loved it because it was all about herself; but

she hated it too because it made her feel like a bill was owing somewhere andhe, Denver, had to pay it. But who she owed or what to pay it with eluded her.

Now, watching Beloved’s alert and hungry face, how she took in every word,

asking questions about the color of things and their size, her downright

craving to know, Denver began to see what she was saying and not just to hear

it: there is this nineteen-year-old slave girl–a year older than her self–

walking through the dark woods to get to her children who are far away. She is

tired, scared maybe, and maybe even lost. Most of all she is by herself and

inside her is another baby she has to think about too. Behind her dogs,

perhaps; guns probably; and certainly mossy teeth. She is not so afraid at

night because she is the color of it, but in the day every sound is a shot or a

tracker’s quiet step.

Denver was seeing it now and feeling it–through Beloved. Feeling how it

must have felt to her mother. Seeing how it must have looked.

And the more fine points she made, the more detail she provided, the more

Beloved liked it. So she anticipated the questions by giving blood to the

scraps her mother and grandmother had told herwand a heartbeat. The monologue

became, iri fact, a duet as they lay down together, Denver nursing Beloved’s

interest like a lover whose pleasure was to overfeed the loved. The dark quilt

with two orange patches was there with them because Beloved wanted it near her

when she slept. It was smelling like grass and feeling like hands– the

unrested hands of busy women: dry, warm, prickly. Denver spoke, Beloved

listened, and the two did the best they could to create what really happened,

how it really was, something only Sethe knew because she alone had the mind for

it and the time afterward to shape it: the quality of Amy’s voice, her breath

like burning wood. The quick-change weather up in those hills—cool at night,

hot in the day, sudden fog. How recklessly she behaved with this whitegirlNa

recklessness born of desperation and encouraged by Amy’s fugitive eyes and her

tenderhearted mouth.

“You ain’t got no business walking round these hills, miss.”

“Looka here who’s talking. I got more business here ‘n you got.

They catch you they cut your head off. Ain’t nobody after me but I know

somebody after you.” Amy pressed her fingers into the soles of the slavewoman’s

feet. “Whose baby that?”

Sethe did not answer.

“You don’t even know. Come here, Jesus,” Amy sighed and shook her head.

“Hurt?”

“A touch.”

“Good for you. More it hurt more better it is. Can’t nothing heal without

pain, you know. What you wiggling for?”

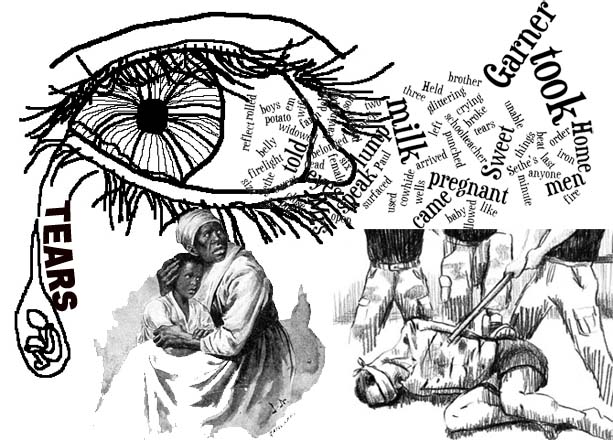

Sethe raised up on her elbows. Lying on her back so long had raised a

ruckus between her shoulder blades. The fire in her feet and the fire on her

back made her sweat.

“My back hurt me,” she said.

“Your back? Gal, you a mess. Turn over here and let me see.”

In an effort so great it made her sick to her stomach, Sethe turned onto

her right side. Amy unfastened the back of her dress and said, “Come here,

Jesus,” when she saw. Sethe guessed it must be bad because after that call to

Jesus Amy didn’t speak for a while. In the silence of an Amy struck dumb for a

change, Sethe felt the fingers of those good hands lightly touch her back. She

could hear her breathing but still the whitegirl said nothing. Sethe could not

move. She couldn’t lie on her stomach or her back, and to keep on her side

meant pressure on her screaming feet. Amy spoke at last in her dreamwalker’s

voice.

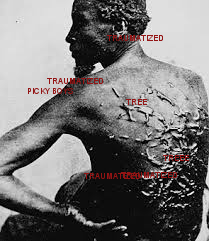

“It’s a tree, Lu. A chokecherry tree. See, here’s the trunk–it’s red and

split wide open, full of sap, and this here’s the parting for the branches. You

got a mighty lot of branches. Leaves, too, look like, and dern if these ain’t

blossoms. Tiny little cherry blossoms, just as white. Your back got a wholeree on it. In bloom. What God have in mind, I wonder. I had me some whippings,

but I don’t remember nothing like this. Mr. Buddy had a right evil hand too.

Whip you for looking at him straight. Sure would. I looked right at him one

time and he hauled off and threw the poker at me. Guess he knew what I was athinking.'”

Sethe groaned and Amy cut her reverie short–long enough to shift Sethe’s

feet so the weight, resting on leaf-covered stones, was above the ankles.

“That better? Lord what a way to die. You gonna die in here, you know.

Ain’t no way out of it. Thank your Maker I come along so’s you wouldn’t have to

die outside in them weeds. Snake come along he bite you. Bear eat you up. Maybe

you should of stayed where you was, Lu. I can see by your back why you didn’t

ha ha.

Whoever planted that tree beat Mr. Buddy by a mile. Glad I ain’t you.

Well, spiderwebs is ’bout all I can do for you. What’s in here ain’t enough.

I’ll look outside. Could use moss, but sometimes bugs and things is in it.

Maybe I ought to break them blossoms open. Get that pus to running, you think?

Wonder what God had in mind. You must of did something. Don’t run off nowhere

now.”

Sethe could hear her humming away in the bushes as she hunted spiderwebs.

A humming she concentrated on because as soon as Amy ducked out the baby began

to stretch. Good question, she was thinking.

What did He have in mind? Amy had left the back of Sethe’s dress open and

now a tail of wind hit it, taking the pain down a step. A relief that let her

feel the lesser pain of her sore tongue. Amy returned with two palmfuls of web,

which she cleaned of prey and then draped on Sethe’s back, saying it was like

stringing a tree for Christmas.

“We got a old nigger girl come by our place. She don’t know nothing. Sews

stuff for Mrs. Buddy–real fine lace but can’t barely stick two words together.

She don’t know nothing, just like you. You don’t know a thing. End up dead,

that’s what. Not me. I’m a get to Boston and get myself some velvet. Carmine.

You don’t even know about that, do you? Now you never will. Bet you never even

sleep with the sun in your face. I did it a couple of times. Most times I’m

feeding stock before light and don’t get to sleep till way after dark comes.

But I was in the back of the wagon once and fell asleep.

Sleeping with the sun in your face is the best old feeling. Two times I

did it. Once when I was little. Didn’t nobody bother me then. Next time, in

back of the wagon, it happened again and doggone if the chickens didn’t get

loose. Mr. Buddy whipped my tail. Kentucky ain’t no good place to be in.

Boston’s the place to be in. That’s where my mother was before she was give to

Mr. Buddy. Joe Nathan said Mr.

Buddy is my daddy but I don’t believe that, you?”

Sethe told her she didn’t believe Mr. Buddy was her daddy.

“You know your daddy, do you?”

“No,” said Sethe.

“Neither me. All I know is it ain’t him.” She stood up then, having

finished her repair work, and weaving about the lean-to, her slow-moving eyes

pale in the sun that lit her hair, she sang: “‘When the busy day is done And my

weary little one Rocketh gently to and fro; When the night winds softly blow,

And the crickets in the glen Chirp and chirp and chirp again; Where “pon the

haunted green Fairies dance around their queen, Then from yonder misty skies

Cometh Lady Button Eyes.”

Suddenly she stopped weaving and rocking and sat down, her skinny arms

wrapped around her knees, her good good hands cupping her elbows. Her slowmoving eyes stopped and peered into the dirt at her feet. “That’s my mama’s

song. She taught me it.”

“Through the muck and mist and glaam To our quiet cozy home, Where to

singing sweet and low Rocks a cradle to and fro.here the clock’s dull monotone

Telleth of the day that’s done,

Where the moonbeams hover o’er

Playthings sleeping on the floor,

Where my weary wee one lies

Cometh Lady Button Eyes.

Layeth she her hands upon

My dear weary little one,

And those white hands overspread

Like a veil the curly head,

Seem to fondle and caress

Every little silken tress.

Then she smooths the eyelids down

Over those two eyes of brown

In such soothing tender wise

Cometh Lady Button Eyes.”

Amy sat quietly after her song, then repeated the last line before she

stood, left the lean-to and walked off a little ways to lean against a young

ash. When she came back the sun was in the valley below and they were way above

it in blue Kentucky light.

“‘You ain’t dead yet, Lu? Lu?”

“Not yet.”

“Make you a bet. You make it through the night, you make it all the way.”

Amy rearranged the leaves for comfort and knelt down to massage the swollen

feet again. “Give these one more real good rub,” she said, and when Sethe

sucked air through her teeth, she said, “Shut up. You got to keep your mouth

shut.”

Careful of her tongue, Sethe bit down on her lips and let the good hands

go to work to the tune of “So bees, sing soft and bees, sing low.” Afterward,

Amy moved to the other side of the lean-to where, seated, she lowered her head

toward her shoulder and braided her hair, saying, “Don’t up and die on me in

the night, you hear? I don’t want to see your ugly black face hankering over

me. If you do die, just go on off somewhere where I can’t see you, hear?”

“I hear,” said Sethe. I’ll do what I can, miss.”

Sethe never expected to see another thing in this world, so when she felt

toes prodding her hip it took a while to come out of a sleep she thought was

death. She sat up, stiff and shivery, while Amy looked in on her juicy back.

“Looks like the devil,” said Amy. “But you made it through.

Come down here, Jesus, Lu made it through. That’s because of me.

I’m good at sick things. Can you walk, you think?”

“I have to let my water some kind of way.”

“Let’s see you walk on em.”

It was not good, but it was possible, so Sethe limped, holding on first

to Amy, then to a sapling.

“Was me did it. I’m good at sick things ain’t I?”

“Yeah,” said Sethe, “you good.”

“We got to get off this here hill. Come on. I’ll take you down to the

river. That ought to suit you. Me, I’m going to the Pike. Take me straight to

Boston. What’s that all over your dress?”

“Milk.”

“You one mess.”

Sethe looked down at her stomach and touched it. The baby was dead. She

had not died in the night, but the baby had. If that was the case, then thereas no stopping now. She would get that milk to her baby girl if she had to

swim.

“Ain’t you hungry?” Amy asked her.

“I ain’t nothing but in a hurry, miss.”

“Whoa. Slow down. Want some shoes?”

“Say what?”

“I figured how,” said Amy and so she had. She tore two pieces from

Sethe’s shawl, filled them with leaves and tied them over her feet, chattering

all the while.

“How old are you, Lu? I been bleeding for four years but I ain’t having

nobody’s baby. Won’t catch me sweating milk cause…”

“I know,” said Sethe. “You going to Boston.”

At noon they saw it; then they were near enough to hear it. By late

afternoon they could drink from it if they wanted to. Four stars were visible

by the time they found, not a riverboat to stow Sethe away on, or a ferryman

willing to take on a fugitive passenger–nothing like that–but a whole boat to

steal. It had one oar, lots of holes and two bird nests.

“There you go, Lu. Jesus looking at you.”

Sethe was looking at one mile of dark water, which would have to be split

with one oar in a useless boat against a current dedicated to the Mississippi

hundreds of miles away. It looked like home to her, and the baby (not dead in

the least) must have thought so too.

As soon as Sethe got close to the river her own water broke loose to join

it. The break, followed by the redundant announcement of labor, arched her

back.

“What you doing that for?” asked Amy. “Ain’t you got a brain in your

head? Stop that right now. I said stop it, Lu. You the dumbest thing on this

here earth. Lu! Lu!”

Sethe couldn’t think of anywhere to go but in. She waited for the sweet

beat that followed the blast of pain. On her knees again, she crawled into the

boat. It waddled under her and she had just enough time to brace her leaf-bag

feet on the bench when another rip took her breath away. Panting under four

summer stars, she threw her legs over the sides, because here come the head, as

Amy informed her as though she did not know it–as though the rip was a breakup

of walnut logs in the brace, or of lightning’s jagged tear through a leather

sky.

It was stuck. Face up and drowning in its mother’s blood. Amy stopped

begging Jesus and began to curse His daddy.

“Push!” screamed Amy.

“Pull,” whispered Sethe.

And the strong hands went to work a fourth time, none too soon, for river

water, seeping through any hole it chose, was spreading over Sethe’s hips. She

reached one arm back and grabbed the rope while Amy fairly clawed at the head.

When a foot rose from the river bed and kicked the bottom of the boat and

Sethe’s behind, she knew it was done and permitted herself a short faint.

Coming to, she heard no cries, just Amy’s encouraging coos. Nothing happened

for so long they both believed they had lost it. Sethe arched suddenly and the

afterbirth shot out. Then the baby whimpered and Sethe looked.

Twenty inches of cord hung from its belly and it trembled in the cooling

evening air. Amy wrapped her skirt around it and the wet sticky women clambered

ashore to see what, indeed, God had in mind.

Spores of bluefern growing in the hollows along the riverbank float

toward the water in silver-blue lines hard to see unless you are in or near

them, lying right at the river’s edge when the sunshots are low and drained.

Often they are mistook for insects–but they are seeds in which the whole

generation sleeps confident of a future.

And for a moment it is easy to believe each one has one–will become allf what is contained in the spore: will live out its days as planned.

This moment of certainty lasts no longer than that; longer, perhaps, than

the spore itself.

On a riverbank in the cool of a summer evening two women struggled under

a shower of silvery blue. They never expected to see each other again in this

world and at the moment couldn’t care less.

But there on a summer night surrounded by bluefern they did something

together appropriately and well. A pateroller passing would have sniggered to

see two throw-away people, two lawless outlaws– a slave and a barefoot

whitewoman with unpinned hair–wrapping a ten-minute-old baby in the rags they

wore. But no pateroller came and no preacher. The water sucked and swallowed

itself beneath them. There was nothing to disturb them at their work. So they

did it appropriately and well.

Twilight came on and Amy said she had to go; that she wouldn’t be caught

dead in daylight on a busy river with a runaway. After rinsing her hands and

face in the river, she stood and looked down at the baby wrapped and tied to

Sethe’s chest.

“She’s never gonna know who I am. You gonna tell her? Who brought her

into this here world?” She lifted her chin, looked off into the place where the

sun used to be. “You better tell her. You hear? Say Miss Amy Denver. Of

Boston.”