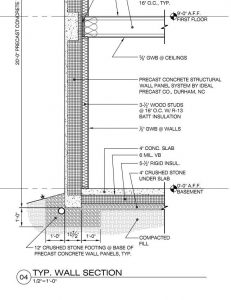

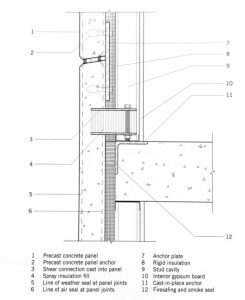

Precast Concrete Wall System

From interior to exterior a precast concrete wall begins with a group of layers consisting of a ½” of gypsum wall board, a 2×4 stud wall and 2” of rigid insulation for thermal protection. This connects to a precast concrete panel through an anchor plate, bolted into the precast panel. At this point of connection two precast panels meet with backer rod and inner sealant and outer sealant for waterproofing. A concrete slab connects to precast panel by a two layers of shear connection cast into the precast panel filled with spray insulation fill. This anchored into the slab and shelf angle on the corner of the slab. Between the shelf angle and precast panel is a space for the fire safing and smoke seal to protect against fires.

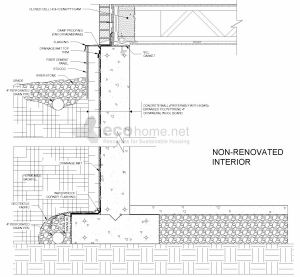

Composite Metal Panel Connections

A composite metal panel can be a “rain screen pressure equalized dry-joint system” meaning it serves to keep water out from penetrating into the building. It allows minimal water penetration where water that enters into the wall system is drained through weep holes. This wall system begins with typical wall of CMU or concrete with sheathing, a weather resistant barrier and insulation with a water barrier in front of it. The metal panel system is attached to the CMU or concrete wall by a attachment grit like an EC-203 with a fastener attached through the CMU or concrete. This piece spans along the CMU or concrete wall to attach the panels on it. The EC-203 is locked in with a EC-202, held together with a smaller fastener on both sides. The EC-202 wraps around the metal panels where two panels ends meet, each with a weep hole and weep baffle to drain out any water penetrated through the wall system. Another wall to keep water out is the use of backing rod and sealant in the wall system of about ½”. The metal panel is around 1-15/16” thick from water barrier to the exterior of the metal panel.

Stainless Steel Rainscreen Panel

Stainless Steel Rainscreen Panel

Rainscreens offer many benefits for exterior wall performance and maintenance. This reliable building envelope resists the elements, and protects against air and water infiltration-provided their connectors are specified correctly.

Will we need exterior insulation?

Yes. Exterior insulation has almost become the design standard in colder climate zones from North Carolina up the East Coast over to the Pacific Northwest. One of the most significant considerations we have seen for specifying the connection of rainscreen panels to the building is the emphasis on the effectiveness of the exterior insulation, as this design approach is so popular due to building codes according to Brian Nelson, general manager at Knight Wall Systems, Deer Park, Wash.

It’s important that the rainscreen connector be easily adjustable so workers in the field can easily fine-tune the installation to achieve precision. “The beauty of a rainscreen is that the waterproofing is taken care of behind the scenes-the rhythm of the rainscreen panels is independent of the waterproofing joints,” says San Francisco-based architect Charles F. Bloszies, FAIA.

“I am more concerned with the structural components beneath the panel,” he says. “The quality of the connections you don’t see are often more important than the finished surface you do see.” says Christopher Costanza, RA, AIA, LEED AP, architect at 9X30 Design Architecture LLP, Rochester, N.Y.

Metal’s Weatherability

Open-joint rainscreen systems are designed to let limited moisture in, so architects must pay close attention to metal’s weatherability when specifying their connectors. A combination of dissimilar metal materials can cause cathodic corrosion. In some cases materials such as aluminum; will corrode if it is near dissimilar metals such as copper which leads to corrosion.

“Aluminum weathers well, as long as it’s not placed up against another dissimilar metal,” says John Barbara, AIA, LEED AP, senior associate at LEO A DALY, Washington, D.C. “If steel and aluminum are used together, a coating is needed to separate the two. Steel-only connectors need to be either coated or galvanized.

Reducing Thermal Bridging

“In a perfect world, we would use a fiberglass clip, which is a localized thermal break you attach to a hat channel,”says, Alex Terzich, AIA, of Minneapolis-based Hammel, Green and Abrahamson “But these are expensive and it’s often not in the cards for us to do that. So we look at different scenarios. Do we use intermittent Z-girts? These localized points of penetration through the insulation work well thermally, but they require a lot more layout and time. Do we use two lines of Z-girts? [They are] horizontals, with verticals on top of that, and where they cross is the one thermal bridge, which helps reduce thermal transmission. It’s a good option but also more material, more time, more cost. What we usually specify is a conventional, continuous linear Z-girt that’s bridging through the insulation, then we take that thermal bridge into account when we specify the insulation type and thickness to make sure we still meet the code-required system Uvalue requirement for the wall.”

Obviously, there are many details to rainscreen connector specification and many others not discussed in this article. Barbara believes it’s these details that often make or break a project, and bring it to the next level. “It really comes down to getting those details finessed,” he says. “The quality of the design documents is critical, but even more important is the builder’s ability to execute them, so good detailing that is buildable and resolved in the studio is essential.”