Open access is not a business model; rather, it is a philosophy and ethos as well as a practice. It expanded and came into full maturity in the mid-aughts after its initial development during the 1990s, followed by several years of innovation in the early-aughts. During this era (the early 2000s), the movement grew significant enough that a turning point had been reached; stakeholders in scholarly communications came together to issue a series of three declarations supporting open access. These three declarations are, in shorthand, called the 3Bs: Budapest (BOAI) (2002), Bethesda (2003), and Berlin (2003).

Open access is not a business model; rather, it is a philosophy and ethos as well as a practice. It expanded and came into full maturity in the mid-aughts after its initial development during the 1990s, followed by several years of innovation in the early-aughts. During this era (the early 2000s), the movement grew significant enough that a turning point had been reached; stakeholders in scholarly communications came together to issue a series of three declarations supporting open access. These three declarations are, in shorthand, called the 3Bs: Budapest (BOAI) (2002), Bethesda (2003), and Berlin (2003).

The concept of knowledge as a public good is referenced in the BOAI:

“An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarly journals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge.”

Open access is at its essence a philosophical notion with the guiding principle that scholarly content should be available to all readers without restriction because knowledge itself is a public good and cannot be bought and sold. The idea of knowledge as a public good derives from the work of Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom’s conception of knowledge-as-commons.

Peter Suber provided an excellent overview of this important economic concept in an essay, originally published in the SPARC Open Access Newsletter (Nov. 2, 2009), reprinted in Knowledge Unbound: Selected Writings on Open Access, 2002–2011. In brief, a public good is “non-rivalrous and non-excludable,” meaning that it is non-competitive and available to anyone and unaffected by consumption. New knowledge only adds to existing knowledge, and anyone can gain knowledge by learning in varied ways. It is important to differentiate knowledge as a public good versus knowledge captured in texts which are not a public good. Suber argued that when knowledge in text form is digital, it is no longer rivalrous or excludable. Unfortunately, the scholarly publishing system has not evolved to embrace this ethos.

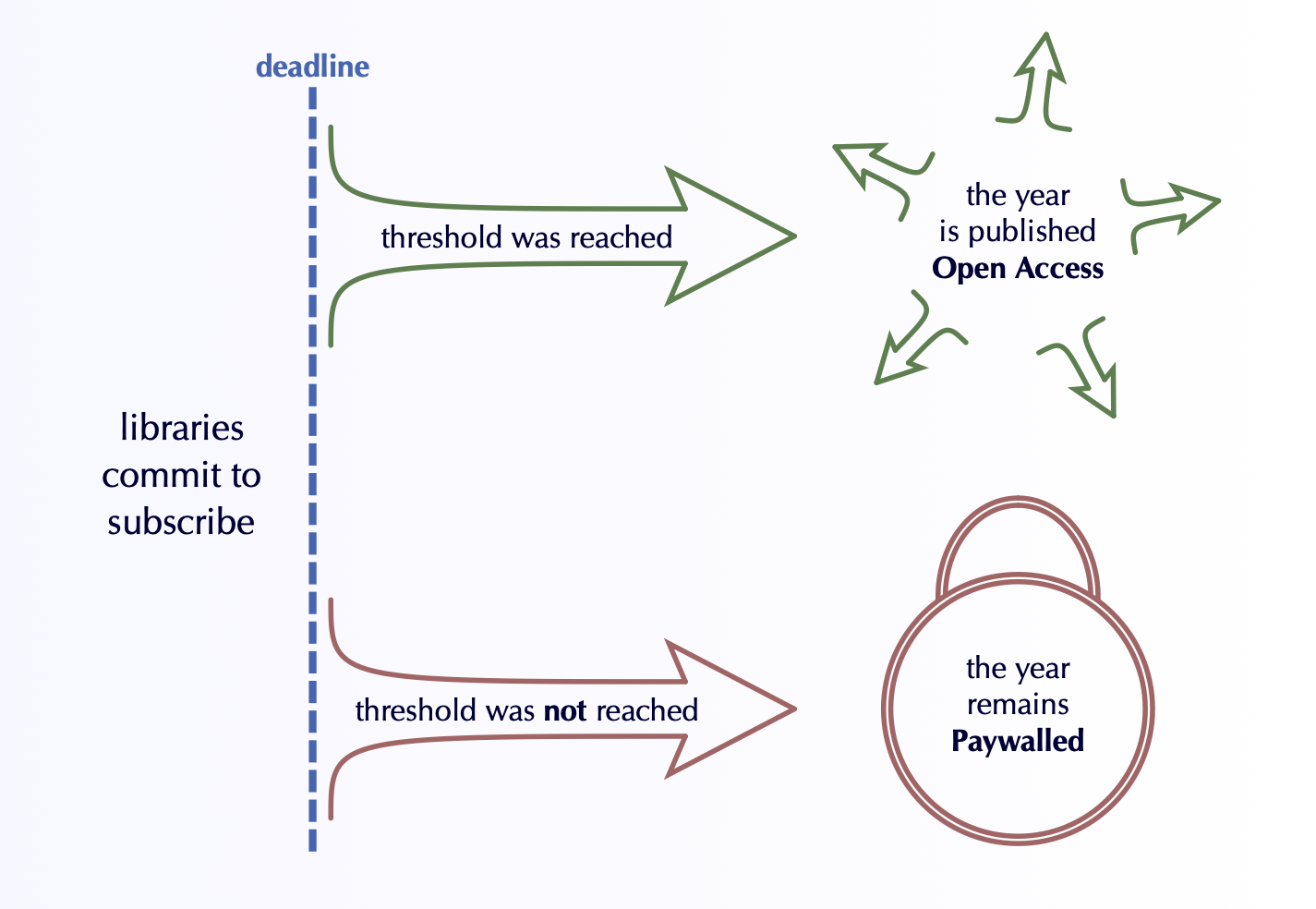

Open access journals, according to the BOAI, “will not charge subscription or access fees, and will turn to other methods for covering their expenses.” This proviso related to “other methods” is important to subsequent discussion of the various models for open access publishing and how article processing charges (author fees) fit in. Open access publishing has increasingly taken the form of a business and this year’s theme for Open Access Week is Community over Commercialization.

When open access is positioned as a business model that will solve the problem of overpriced journals, this interpretation of open access has proven troubled. Open access has not resulted in moderating journal pricing, whether for subscriptions or, in our current environment, author fees for immediate open access. The 20th anniversary of the BOIA declares that diamond open access, open access without fees to authors, should be supported instead of commercialized open access. Lastly, let’s not forget that platforms like CUNY Academic Works also allow us to share our work freely.

this blog post is adapted from my forthcoming book (Winter/Spring 2024) from the Association of College and Research Libraries.

We’re running our annual Academic Works Demystified workshop next week, Nov. 1, 4-5 PM. The workshop addresses what is Academic Works and how it benefits you as a scholar. You will learn more about how and why publishers allow you to contribute to Academic Works and the many benefits to sharing your scholarship openly to you, your students, and the public. The workshop will be on Zoom.

Faculty whose scholarship focuses on teaching and learning may be interested to learn that the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Stony Brook University recently launched a new journal, International Journal of Transformative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

Faculty whose scholarship focuses on teaching and learning may be interested to learn that the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Stony Brook University recently launched a new journal, International Journal of Transformative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

This post, the first in a series, introduces City Tech faculty to free-to-author, immediate open access publishing options.

This post, the first in a series, introduces City Tech faculty to free-to-author, immediate open access publishing options.

Open Access Week is this month and we’re celebrating by posting a series of blogs about WHY OPEN ACCESS MATTERS [yes, I’m being shouty here]. Last May, the Higher Education Leadership Initiative (HELIOS) invited Erin McKiernan, formerly head of the ScholCommLab, and currently community manager at Open Funders Research Group’s community manager and professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City.

Open Access Week is this month and we’re celebrating by posting a series of blogs about WHY OPEN ACCESS MATTERS [yes, I’m being shouty here]. Last May, the Higher Education Leadership Initiative (HELIOS) invited Erin McKiernan, formerly head of the ScholCommLab, and currently community manager at Open Funders Research Group’s community manager and professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City.

Scholarship for the Public Good: Paths to Open Access Online

Scholarship for the Public Good: Paths to Open Access Online