Presentation, Text Only.

Category: Uncategorized (Page 4 of 19)

Resources :

https://www-sciencedirect-com.citytech.ezproxy.cuny.edu/science/article/pii/S0363811119302590 (Poltical underground movement)

https://medium.com/@sthmrrll/why-i-prefer-the-other-nike-ad-no-one-is-talking-about-4a4e09ba683e

https://notesmatic.com/2019/10/nike-dream-crazier-advertisement-analysis/ (logos, pathos ethos)

http://joshferrer.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PR-Case-Study.pdf

http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9004856&fileOId=9004858 ( ungerdround plus poltical views on dream crazy campaign)

https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/3484zj482 ( sassuare signs and symbols + barthas rhetoric)

https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1742&context=etd

http://www.worthnotweight.com/marketing-success-nikes-shaquem-griffin/

Barnhart, Brent. “How to Make Sure You’re Marketing to Gen Z the Right Way.” Sprout Social, 11 Nov. 2019, sproutsocial.com/insights/marketing-to-gen-z/.

Codella, Daniel. “The Winning Coca-Cola Formula for a Successful Campaign.” Wrike, Wrike, 6 Apr. 2018, www.wrike.com/blog/winning-coca-cola-formula-successful-campaign/.

Crawford, Elizabeth Crisp, and Jeremy Jackson. “Philanthropy in the Millennial Age: Trends toward Polycentric Personalized Philanthropy.” Independent Review, vol. 23, no. 4, 2019, p. 551+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A581175535/AONE?u=cuny_nytc&sid=AONE&xid=0dea4ab3. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

Heller, Steven. “The Underground Mainstream.” Graphic Design Theory: Readings from the Field, by Helen Armstrong, Princeton Architectural Press, 2012, pp. 98–101.

Henderson, Geraldine Rosa, and Jerome D. Williams. “From Exclusion to Inclusion: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Marketplace Diversity and Inclusion.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, vol. 32, 2013, pp. 1–5. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43305308. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

“How a Campaign Got Its Start Down Under – News & Articles.” The Coca-Cola Company: Refresh the World. Make a Difference, The Coca-Cola Company, 25 Sept. 2014, www.coca-colacompany.com/news/how-a-campaign-got-its-start-down-under.

Kozinets, Robert V., et al. “Networked Narratives: Understanding Word-of-Mouth Marketing in Online Communities.” Journal of Marketing, vol. 74, no. 2, 2010, pp. 71–89. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20619091. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

Kumar, V. “Evolution of Marketing as a Discipline: What Has Happened and What to Look Out For.” Journal of Marketing, vol. 79, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–9. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43784378. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Liu, Yizao, and Rigoberto A. Lopez. “The Impact of Social Media Conversations on Consumer Brand Choices.” Marketing Letters, vol. 27, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26177931. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

O’Connor, Padraig. “What To Know When Marketing To Millennials.” Social Media Week, 28 July 2015, socialmediaweek.org/blog/2015/07/marketing-to-millennials/.

Sonesson, Göran. “Rhetoric of the Image.” Encyclopedia of Semiotics. : Oxford University Press, , 2007. Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 28 Nov. 2020 <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195120905.001.0001/acref-9780195120905-e-248>.

Tarver, Evan. “Why the ‘Share a Coke’ Campaign Is So Successful.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 28 Aug. 2020, www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/100715/what-makes-share-coke-campaign-so-successful.asp.

Whitler, Kimberly A. “Why Word Of Mouth Marketing Is The Most Important Social Media.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 9 Sept. 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/kimberlywhitler/2014/07/17/why-word-of-mouth-marketing-is-the-most-important-social-media/?sh=4b98dc9e54a8.

Staber, Margit. “Swiss Design Today.” Design Quarterly, no. 60, 1964, pp. 1–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4047306. Accessed 30 Nov. 2020.

Gaddy, James. “Altitude: Contemporary Swiss Graphic Design.” Print, vol. 61, no. 3, May 2007, p. 166. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=25070744&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Mauderli, Laurence. “Positioning Swiss Design: The ‘Schweizerischer Werkbund’ and ‘L’Oeuvre’ at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century.” The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 – the Present, no. 25, 2001, pp. 25–37. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41809311. Accessed 30 Nov. 2020.

What is referred to as mainstream today was born from what was once considered underground. I believe this is a revolving cycle not just now in contemporary times but even in the past. Heller says that the mainstream takes the underground and call it cool. Which is to me a form of exploitation and in some case could be looked at as cultural appropriation. The merger between the two is a fine line, because sometimes it seems like the transition from underground to mainstreams feels seamless. The battle between the two can be very frustrating for creators themselves especially when business gets involved. As Heller said mass marketers steal ideals from visionaries and thens slightly change the idea or in some cases don’t change it at all, which is a very nasty practice but still occurs to this day.

Bibliography

Heller, Steven. “Street theater.” Print, vol. 50, no. 3, May-June 1996, p. 29+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A18614265/AONE?u=cuny_nytc&sid=AONE&xid=2bf5f143.

“Constructivism Movement Overview.” The Art Story, m.theartstory.org/movement/constructivism/.

Jodi. “What Is Constructivism.” Austin Artists Market, 12 Nov. 2018, www.austinartistsmarket.com/what-is-constructivism/.

“Paula Scher.” Pentagram, Pentagram, www.pentagram.com/about/paula-scher.

“The Public Theater – Story.” Pentagram, Pentagram, www.pentagram.com/work/the-public-theater/story.

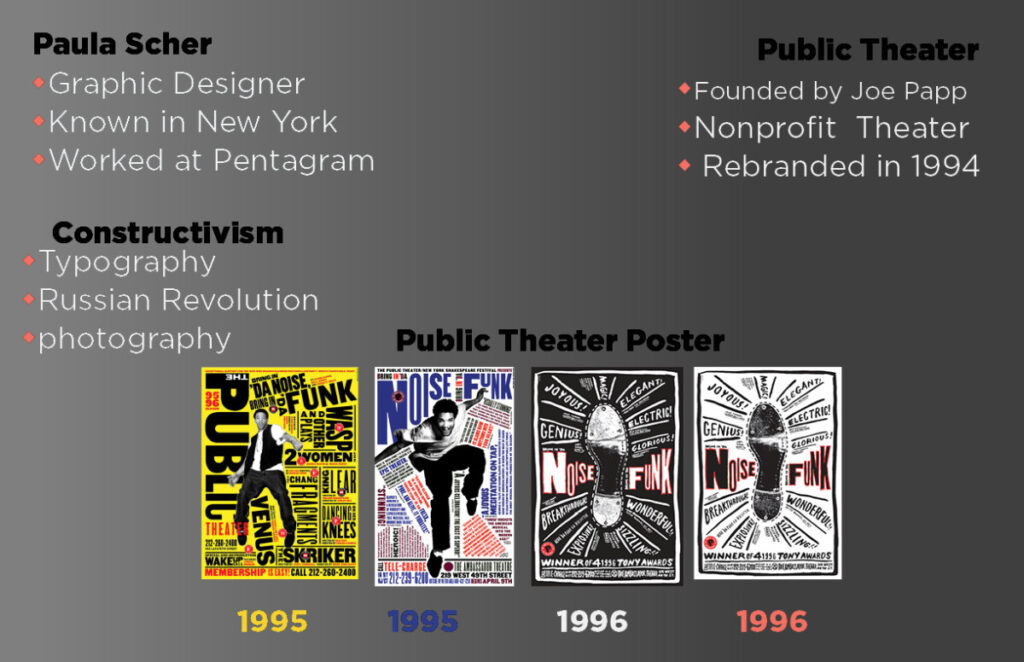

The old and new art styles have always evolved and collided with each other. It has always influenced our designs in the present times. Steven Heller reveals to us in “The Underground Mainstream” that the term Underground is the name given to the different Avant-Garde movements and styles. This is the core foundation in design; while mainstream is the embracing of all things cool, stylish, edgy, hip, and new. In the article “The Underground Mainstream” the two correlate and work hand in hand with each other. Thus, playing a role in contemporary art and designs of today. The old have set the path and style we want to achieve, with the incorporation of something new and in time with today.

It makes it easier for our viewers to understand and relate to. Heller tells us that advertising campaigns borrow characteristics from Avant-garde European Modern art. This combination as Steven classifies it is known as “cultural jamming”. At this time he wrote “ Underground denizens attack the mainstream for one of two reasons: to alter or to join, although sometimes both.” Many choose to embrace it and join this on their own accord. Some classified it as a rebellious design in their eyes. Moreover, those who choose mainstream must be able to make an impact larger than their circumscribed circles.

Today, we can see many companies, advertising campaigns, and products take characteristics from the past styles and integrating them with new styles. Creating a combination that makes design transgress and go beyond its normal expectations. The BMW company is heavily influenced by Marinetti futurism movement. This movement has molded itself into our daily lives. Making accessible and as an extension of ourselves. Many artist seek to incorporate the acts of futuristic traits in their designs. I want to focus on the evolution of car designs throughout time. Looking at the styles back then and comparing it to now. BMW 2020 logo represents “Introduction to brand communication only” and the company slogan “Sheer Driving Pleasure”. Ties in this dichotomy as they seek to express these in their car design. The BMW i8 (I12) is an embodiment of the momentum of speed, mobility, and sound. Which is the backbone and base of futurism. The i8 (I12) set the framework of the endless possibilities a car can undergo. The butterfly doors can foreshadow or possibility that a flying car is in the making for the future.

Bibliography

Heller, Steven. “Underground Mainstream.” Design Observer, 10 Apr. 2008, designobserver.com/feature/underground-mainstream/6737.

Bragato, S. (2019). Futurism. Italian Studies, 74(1), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2019.1537111

Baranello, A. (2010). The Deus (ex) Macchina: the Legacy of the Futurist Obsession with Speed.

Dijk, Y. (2010). The emergence of hybrid-electric cars: Innovation path creation through co-evolution of supply and demand. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 77(8), 1371–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.05.001

Lee, S. (2017). Research of Future Furniture Design: Exploring Trends and Aesthetics in Futurism (2017). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

My take on “the concept of mainstream vs. underground relevant in contemporary design” is yes, he does believe that mainstream vs. underground is relevant in contemporary times. The way he describes mainstream stealing from underground culture is like a necessary evil, for example near the end of the Heller reading he states that underground designers who eventually join the mainstream at their own accords, do so because it is where they believe they can make the most impact on the medium and possibly even culture. He also believes the relationship between the two is almost parasitic in nature as mainstream steals from alternative culture, and sometimes lines begin to blur between the two.

An example of how parasitic mainstream can be comes from a YouTube channel called wisecrack where they discuss Banksy. They state how he is a street artist, an anticapitalist, and antiestablishment. Yet his art can be worth 100,000 or even millions of dollars and are often removed, as well as being sheltered from the elements. Another example of how mainstream leeches of something underground or not mainstream comes from the article Into the mainstream: Shifting authenticities in art where art of African, Aboriginal, Native American, others of non-European origins were once seen as primitive, but are now being shown in art shows and galleries.

While I haven’t made my final decision on what my final project will be, I am leaning towards a series of pride subway posters and I think it fits between an odd middle ground of mainstream and underground. I say that because when the fight for LGBT rights began, it wasn’t widely accepted but as time went people began to accept LGBT people or at least be more open minded on LGBT people. But when it comes to companies, these corporations are hesitant to show full on support. They might sprinkle some stuff here and there up until pride month comes around and they go full on support mode then go back to normal. They do it because it’s “cool” or “fashionable” like when companies go full on gay during pride month.

Heller, Steven. “Underground Mainstream.” Design Observer, 10 Apr. 2008, designobserver.com/feature/underground-mainstream/6737.

Price, Sally. “Into the Mainstream: Shifting Authenticities in Art.” American Ethnologist , vol. 34, no. 4, Nov. 2007, pp. 603–620.

Scherker, Amanda, director. Is BANKSY Deep or Dumb? – Wisecrack Edition, Youtube, 16 Mar. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLGW4e1rqig.

To my understanding of Helen Armstrong’s “Introduction: Revisiting the Avant-Garde” she talks about how designers should have a sense of anonymity. Have the work be known but not the designer. This is something she states in the reading, “Design is a social activity. Rarely working alone or in private, designers respond to clients, audiences, publishers, institutions, and collaborators. While our work is exposed and highly visible, as individuals we often remain anonymous, our contribution to the texture of daily life existing below the threshold of public recognition.” Then she also states how in the early 20th century graphic design was built on anonymity and goes on to say that in the 50s and 60s “Swiss-style design solidified the anonymous working space of the designer inside a frame of objectivity.”

In the Bruno Munari reading, it seems like he is trying to say that art is mass & public affair and it should not be only accessible to the wealthy. He also mentions how artists should be humbled by getting down from their pedestal and design a butcher’s sign (if they know how to do it), and to cast off “the last rags of romanticism and become active as man among men.” He also mentions that an industrial designer is an engineer of sorts, but a designer in terms of graphics/art is a planner with an aesthetic sense, gives equal weight to each part. Which helps a designer play their role sufficiently as a communicator, someone who relays a message and informs the public.

One problem designers face is social responsibility, something that Armstrong talks about in her reading. She mentions how designers are being critical by using their designs. Instead of being complicit with corporations. Which dates back to when Rodchenko and Lissitzky where active. They were trying to bring about change, something revolutionary but when international style came into the scene, designers became part of corporate America. Then it began to change again as designers began to rebel, they began to critique society, they began to work with activists, they began to bring social changes. Basically, I think she is saying is that while yes we do need to make a living, there comes a point where are social and moral integrity does not get undermined by the corporations and clients we work for.

Recent Comments