*boon – The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a boon as a benefit or favor that is given in answer to a request

**lea – According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a lea refers to grassland or pasture.

[1] A pagan is described by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as an irreligious or hedonistic person. The speaker of the poem makes a connection between paganism and Greek mythology because Greek mythology is regarded as irreligious or pagan by the Christian religion. The poem’s writer, William Wordsworth, was raised as a Christian in England.

[1] Proteus rising from the sea

The reference of Proteus in the poem stems from ancient Greek mythology. Proteus according to Greek mythology is a shape-shifting, all-knowing sea-god who was also known as “The Old Man of the Sea.” This sea-god was the son and servant of Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea. One of Proteus’s responsibilities is the herding of Poseidon’s seals and it was not uncommon to see him rise from the sea around noon to slumber among the seals. Legend has it that it is at that time that the sea-god could be captured. In exchange for his release, he would grant his captor the answer to any one question that he/she would ask.

[1] Triton is a sea-god from Greek mythology. He is the son of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Amphitrite, the goddess of the sea. According to Greek mythology, Triton was described as “The Messenger of the Sea” – a merman who lives with his parents in a golden palace beneath the sea. Triton is known for carrying a large twisted conch seashell. By blowing this shell/horn, Triton was able to control the waves of the sea by either calming them or agitating them.

Explication of William Wordsworth’s “The World is Too Much with Us”

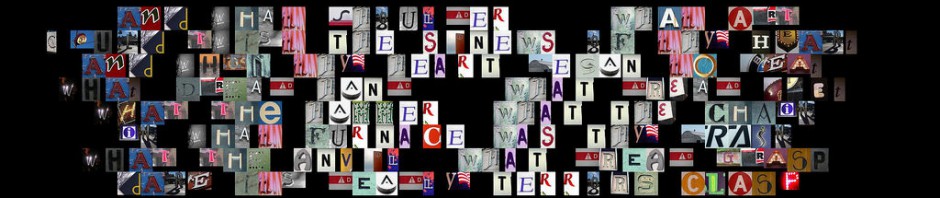

William Wordsworth uses his romantic sonnet, “The World Is Too Much With Us” to strongly voice his objection to mankind’s focus on the acquisition of material commodities and the disconnection that has developed between mankind and nature. The tone of the poem is generally an angry one; however, the poem’s tone becomes less aggressive as the poem comes to a close. In addition to tone, the poet uses the figures of speech, personification and simile, to emphasize the comparisons between the gift of mankind’s own heart and the gifts given by elements in nature. Wordsworth expresses that, as people, we have been wasting our powers by focusing on getting and spending. He even states that he would prefer to be a pagan who appreciates objects of nature rather than to be a man whose materialistic obsession leaves him disconnected from nature.

In the first two lines of the poem, the speaker states that “The world is too much with us; late and soon, /Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers”. These introductory lines begin to show the poet’s disapproval of the way in which people are living. “The world is too much with us; late and soon.” This phrase conveys that the poet feels that nature or “the world” was always overwhelming for mankind that man never paid attention to it. Instead, mankind’s attention was placed on the pursuit of material things (“getting and spending”). This is something that Wordsworth views as a waste of mankind’s existence as he states that “…we lay waste our powers.” The poet’s choice of words in these lines is much more effective as they are than if this piece were arranged as prose. For example, to say that “we lay waste our powers” is more effective than if the poet had said, “We are not using our existence effectively.”

In lines 3 and 4 of the poem, the speaker states that “Little we see in Nature that is ours; /We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!” In the third line of the poem, the poet shows the grave disconnection mankind and nature. This line also connects to mankind’s consumerism and to the fact that despite mankind’s obsession in owning material things, he does not own many things in nature. This may be a reason for mankind’s disconnection from nature since there are few things therein that man can own, buy or sell. In line 4, the speaker states that “We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!” A boon refers to a blessing or gift that is given as an answer to a request. Sordid is synonymous with ignoble, wretched and vile. This means that despite man has given his heart away, this gift is not a noble one. This may mean that mankind’s obsession with acquiring material things through consumerism has caused a disconnection with between mankind and nature and has, in turn, caused his heart – one’s noblest gift – to be vile.

In lines 5 through 9, the poet gives examples of things in nature that give up their true essences in ways that are nobler and more acceptable than mankind’s sordid heart. “The Sea bares her bosom to the moon; /The winds that will be howling at all hours, /And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers; /For this, for everything, we are out of tune” The poem’s ninth relates to lines 5 through 8 which show an interconnection among natural objects in the world. Despite mankind lives in the world, he is still “out of tune” with this interconnection. All in nature give up their noblest of boons within this interconnection; however, mankind’s heart which he gives away is “a sordid boon!” In this these lines, Wordsworth uses personification as the tool to emphasize the interconnection that the elements in nature share and also to emphasize mankind’s disconnection from his natural environment. By personalizing the Sea and the wind, the poet gives these natural elements humanlike characteristics and shows that even they can share connections with each other; while mankind, being truly human, is unable to participate in these connections due to his focus on consumerism. In lines 6 and 7, the poet uses the figure of speech, simile, to compare the wind to sleeping flowers. This comparison gives the reader an idea of just how much the wind gives. The howling wind gives up its might and howl – its essence – and becomes as mild as sleeping flowers. This is a truly worthy boon as opposed to the wretched heart of man.

Lines 10 and 11 state, “It moves us not – Great God! I’d rather be /A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;” In line 10, the poet seems to be angrily surprised at mankind’s indifference. This line may be showing the poet’s disgust at the fact that mankind is not even concerned about his disconnection for nature as he goes about life only focusing on “getting and spending.” This line may also be conveying the poet’s disgust toward the fact that mankind remains unmoved by nature and the beautiful connections that are shared therein. A glimpse of the speaker’s religious beliefs is given in lines 10 and 11 of the poem. The speaker may be Christian due to references made to “Great God!” The capitalization in the ‘g’ in God is generally used for the god of the Christian faith. A pagan, according to the Christian faith is one who is irreligious or one who does not believe in God. The poem’s speaker is so opposed to mankind’s indifference, disconnection from nature and obsession with consumerism that he states that he would prefer to be a “Pagan” that is raised on outdated beliefs than to be a materialistic person who is disconnected from nature.

In lines 12 through 14, the poem’s tone shifts to a less angry, less aggressive tone. In these lines, the poet expresses scenes that he may prefer to experience had he been raised as a pagan as opposed to being brought up as a Christian raised on consumerism and disconnected from nature. He describes standing on a grassy pasture and observing things that would make him feel less unhappy and hopeless. The poet mentions that, a pagan, he may “have glimpses if Proteus rising from the sea; /Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.” Both observances of sea-gods would not have been possible as a Christian because Christians do not believe in Greek mythology – or any other god than their own. This shows how much the poet is opposed to mankind’s disconnection from nature and focus on consumerism. So opposed is he that he is willing to give up his own religious beliefs to attain a connection to nature and lose focus on “getting and spending.” The fact that the speaker would prefer to stand in a pasture and observe the two mythical sea-gods may also be a sign that he has given up on mankind and prefers to connect himself with a fictitious, mythical world rather than to be connected to the real world in which mankind is disconnected from nature. The shift in the poem’s tone is crucial in conveying the idea that the speaker has given up on mankind. It is as if he has given up on trying to convey the message of mankind’s disconnection from nature. To him, all is lost.

Bibliography

“Boon.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Web. 30 April 2012. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/boon>.

“Lea.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Web. 30 April 2012. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lea>.

“Proteus”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 30 Apr. 2012 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/480043/Proteus>.

“PROTEUS : Sea-God, the Herdsman of Seals.” THEOI GREEK MYTHOLOGY, Exploring Mythology & the Greek Gods in Classical Literature & Art. Web. 30 Apr. 2012. <http://www.theoi.com/Pontios/Proteus.html>.

“Proteus (Greek mythology).” The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia®. 2005. Columbia University Press 30 Apr. 2012 <http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Proteus+(Greek+mythology)>.

“Triton”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 30 Apr. 2012 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/606023/Triton>.

“Triton.” Encyclopedia Mythica. 2012. Encyclopedia Mythica Online.30 Apr. 2012 <http://www.pantheon.org/articles/t/triton.html>.

“TRITON : Sea-God, Merman.” THEOI GREEK MYTHOLOGY, Exploring Mythology & the Greek Gods in Classical Literature & Art. Web. 30 Apr. 2012. <http://www.theoi.com/Pontios/Triton.html>.

Wordsworth, William. “The World Is Too Much With US.” Poetry: An Introduction. Ed. Michael Myer. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2010. 247. Print.

“XXII. D. The Water Deities. Vols. I & II: Stories of Gods and Heroes. Bulfinch, Thomas. 1913. Age of Fable.” XXII. D. The Water Deities. Vols. I & II: Stories of Gods and Heroes. Bulfinch, Thomas. 1913. Age of Fable. Web. 08 May 2012. <http://www.bartleby.com/181/224.html>.