Introduction to Stress

Key Points

- To a scientist, a stressor is any action or situation that places special physical or psychological demands on a person, and can be anything that can unbalance an individual’s equilibrium.

- Stress may stem from a major life change, or it may be a built-in part of one’s daily life—a constant and unconscious background experience, like the noise of a city, or the daily chore of driving a car.

- Stressors can be either negative or positive. Distress, or negative stress, is thought to be extreme, overwhelming, and out of a person’s control, while eustress, or positive stress, can be motivating and helpful.

- When we experience stress, our body responds with an unconscious preparation for the flight or fight response.

- Prolonged psychological stress may negatively impact health, and has been cited as a factor in cognitive impairment with aging, depressive illness, and expression of disease.

Stress can be defined in many different ways, depending on the person experiencing it and the perspective used to understand it. One basic definition of stress is “a psychological feeling of strain and pressure.” Behavioral medicine and health psychology are two approaches to analyzing and discussing stress.

To scientists, a stressor is any action or situation that places special physical or psychological demands upon a person, and can be anything that can unbalance the individual’s equilibrium. Stress may stem from a major life change, or it may be a built-in part of one’s daily life; it can be a constant and unconscious background experience, like the noise of a city, or the daily chore of driving a car. When people are faced with demands to which they feel unable to adequately respond, they are motivated to do something to change the situation. The nature of this response depends on a combination of different factors, including the extent of the demand, the personal characteristics and coping resources of the person, the constraints on the person trying to cope, and the support received from others.

Distress vs. Eustress

Stress can be either positive (eustress) or negative (distress). Importantly, the body itself cannot physically discern between distress or eustress; the distinction is dependent on the experience of the individual experiencing the stress. Distress, or negative stress, has negative implications, and is usually perceived to be potentially overwhelming and out of a person’s control. Catastrophes, illnesses, and accidents tend to be the focus of negative stress. Eustress, or positive stress, on the other hand, is the positive emotional or cognitive response to stress that is healthy; it gives a feeling of fulfillment or happiness. Eustress has a positive correlation with life satisfaction and hope because it fosters challenge and motivation toward a goal. Any event can cause either distress or eustress, depending on how the individual interprets the information. For example, traumatic social events may cause great distress, but also eustress in the form of resilience, coping, and fostering a sense of community.

Stress and Health

Prolonged psychological stress may negatively impact health, and has been cited as a factor in cognitive impairment with aging, depressive illness, and expression of disease. There is evidence that certain negative mental states (such as depression and anxiety) can directly affect physical immunity through the production of stress hormones, such as catecholamines and glucocorticoids. Stress management is the application of methods to either reduce stress or increase tolerance to stress. Relaxation techniques are physical methods used to relieve stress. Psychological methods include cognitive therapy, meditation, and positive thinking, which work by reducing the response to stress. Improving relevant skills, such as problem-solving and time-management skills, reduces uncertainty and builds confidence, which also reduces the reaction to negative stress-causing situations in which those skills are applicable.

How the Body Responds to Stress

Key Points

- The interactions of endocrine hormones that have evolved to stabilize the body’s internal environment can be disrupted by stress.

- The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus.

- The hormones epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) are released by the adrenal medulla.

- Epinephrine and norepinephrine increase blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver and skeletal muscles to break down glycogen and by stimulating glucose release by liver cells. Epinephrine and norepinephrine are collectively called catecholamines.

- Stressors are stimuli that disrupt homeostasis.

- Although our bodies can respond to and deal with stress in the short term, long-term exposure to stress hormones can have detrimental effects.

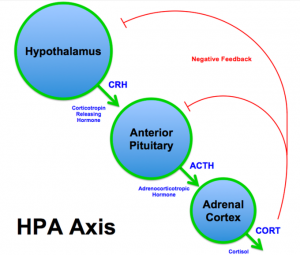

The body responds to stress in certain physiological ways. When a threat or danger is perceived, the body responds by releasing hormones that will prepare it for the fight-or-flight response. The main physiological structure involved in this response is known as the HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary gland–adrenal gland) axis. Such interactions of the endocrine hormones have evolved to ensure that the body’s internal environment remains stable; however, stress can disrupt this stability. Stimuli that disrupt homeostasis in this way are known as stressors.

The Fight-or-Flight Response

When our bodies are faced with a stressor—any trigger that leads to a stress response—certain physical processes take place. The body reacts in a primitive sense to what it perceives as impending danger in what is colloquially termed the fight-or-flight response (sometimes “fight-flight-or-freeze”). Blood from your skin, organs, and extremities is directed to the brain and larger muscles in preparation to fight the impending danger or flee from it. In addition, your senses (especially vision and hearing) are heightened, glucose and fatty acids are released into the blood stream for energy, and your immune and digestive systems all but shut down to provide you with the necessary energy to fight the stressor. The HPA axis coordinates all these physiological changes. Health psychology focuses on this physical reaction and what it means for a person’s health and well-being.

Observable Symptoms of Stress

Stress produces numerous symptoms that vary according to person, situation, and severity. Problems resulting from stress include decline in physical health or mental health, a sense of being overwhelmed, feelings of anxiety, overall irritability, insecurity, nervousness, social withdrawal, loss of appetite, depression, panic attacks, exhaustion, high or low blood pressure, skin eruptions or rashes, insomnia, lack of sexual desire (sexual dysfunction), migraine, gastrointestinal difficulties (constipation or diarrhea), heart problems, and menstrual symptoms.

Stress and the body

This diagram shows the effects of stress on various parts and systems of the body.

The HPA Axis

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) is a complex set of direct influences and feedback interactions among three endocrine glands: the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The HPA axis is a major part of the neuroendocrine system that, among other things, controls reactions to stress.

The HPA system reacts within a person’s brain, and it releases the hormone cortisol from the adrenal gland when a person is exposed to a stressor. Cortisol is most likely to be activated when a person is placed in a situation to be socially judged or evaluated, and therefore under extreme levels of stress. Higher and more prolonged levels of cortisol in the bloodstream are found in those suffering from chronic stress.

The stress response

The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus produces Corticotropin Releasing Hormone (CRH), which activates Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) production in the Anterior Pituitary, which activates Cortisol production in the Adrenal Cortex. The Cortisol influences negative feedback to the Hypothalamus and the Anterior Pituitary.

Although our bodies can respond to and deal with stress in the short term, long-term exposure to stress hormones can have detrimental effects. For example, it can lead to a decrease in memory function and physical performance. This is because glycogen reserves, which provide energy in the short-term response to stress, are exhausted after several hours and cannot meet long-term energy needs. If glycogen reserves were the only energy source available, neural functioning could not be maintained once the reserves became depleted due to the nervous system’s high requirement for glucose.

Stress Hormones and Sympathetic Nervous System

The following are simplified steps that a person’s nervous system goes through when it deals with a stressful situation:

- Blood from the skin, internal organs, and extremities, is directed to the brain and large muscles in preparation for “fight” or “flight.”

- Your senses are heightened, especially vision and hearing.

- Glucose and fatty acids are forced into the bloodstream for energy.

- The immune and digestive systems are virtually shut down to provide all the necessary energy to respond to the perceived threat.

The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus. Stressful stimuli cause the hypothalamus to signal the adrenal medulla (which mediates short-term stress responses) via nerve impulses, and the adrenal cortex (which mediates long-term stress responses) via the hormone adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which is produced by the anterior pituitary. When presented with a stressful situation, the body responds by calling for the release of hormones that provide a burst of energy. The hormones epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) are released by the adrenal medulla.

Epinephrine and norepinephrine increase blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver and skeletal muscles to break down glycogen, and by stimulating glucose release by liver cells. Additionally, these hormones increase oxygen availability to cells by increasing the heart rate and dilating the bronchioles. The hormones also prioritize body function by increasing blood supply to essential organs such as the heart, brain, and skeletal muscles, while restricting blood flow to organs not in immediate need, such as the skin, digestive system, and kidneys. Epinephrine and norepinephrine are collectively called catecholamines.

Experimental Research on the Effects of Stress

Research has found that maintaining good health has a positive influence on reducing and coping with stress. Behaviors such as exercise, meditation, deep breathing, good eating habits, and getting enough sleep can help individuals better handle stress and avoid negative effects such as increased likelihood of sickness and poor digestion. Unfortunately, stress can have a negative impact on the motivation to maintain these healthy behaviors.

While psychological stress alone has not been proven to cause cancer, prolonged psychological stress may affect a person’s overall health and ability to cope with cancer. Evidence from experimental studies suggests that psychological stress levels can affect a tumor’s ability to grow and spread. Studies in mice and human cancer cells grown in a laboratory have found that the stress hormone norepinephrine may promote angiogenesis and metastasis. “Angiogenesis” refers to the development and formation of new blood vessels. “Metastasis” refers to the transference of a bodily function or disease to another part of the body, specifically the development of a secondary area of disease remote from the original site.

Stress and Cardiovascular Disease

Key Points

- Medical researchers are not sure exactly how stress increases the risk of heart disease. Stress itself might be a risk factor, or it could be that high levels of stress make other risk factors worse.

- Stress not only increases a person’s tendency to participate in unhealthy activities, it also triggers physiological responses which expose a person to heart disease.

- Research has also revealed that Type A personalities who multi-task, push themselves with deadlines, and become easily frustrated are much more prone to develop heart disease.

- Many people are beginning to focus on changing unhealthy habits in order to achieve better lives by modifying diets and exercising more, but mental health is still largely neglected.

Cardiovascular disease has a number of behavioral risk factors, some of which are related to chronic stress. Studies on people who died of a sudden heart attack in the 1970s indicated that these people had experienced more stressful life events in the six months preceding the attack than did those who survived. Medical researchers are not sure exactly how stress increases the risk of heart disease. Stress itself, and the physiological responses the body has to it, might be a risk factor. However, it could be that high levels of stress make other risk factors (such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure) worse. Many researchers argue that the relationship between stress and cardiovascular disease is a combination of these factors.

Stress and Cardiovascular Disease

There has been a lot of research in this field over the last two decades, and the results obtained show clearly that excessive stress can lead to the following:

- increase in heart rate;

- increase in blood pressure;

- increased concentration of fat in blood;

- increased blood sugar;

- increased cholesterol in blood;

- increased blood clotting;

- increased deposition of fat and cholesterol in the arteries;

- spasm of coronary and other arteries.

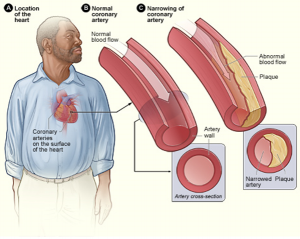

This shows us that stress in itself is an influential risk factor—that even in the absence of other risk factors, it can become responsible for coronary heart disease. If stress itself is a risk factor for heart disease, it could be because chronic stress exposes your body to unhealthy, persistently elevated levels of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Stress not only increases a person’s chances of participating in unhealthy activities (unhealthy eating habits, not exercising due to work load, drinking alcohol, and smoking), it also triggers the physiological responses that predispose a person to heart disease. Chronic stress increases both blood pressure and the risk of atherosclerosis, both of which increase the risk of heart disease. Stress may lead to obesity and diabetes, which are both linked to cardiovascular disease.

Atherosclerosis

Stress can lead to blockages of the arteries, known as atherosclerosis.

Stress and Personality Types

In the 1950, researchers identified two disparate personality types that may impact someone’s chances of developing coronary heart disease. They named these personality types Type A, which tends to increase risk of heart disease, and Type B, which tends to decrease risk of heart disease.

Type A individuals tend to be ambitious, achievement oriented, rigidly organized, highly status-conscious, impatient, highly time-focused, and often take on more than they can handle. People with Type A personalities are often high-achieving workaholics who multi-task, push themselves with deadlines, and become frustrated by delays and ambivalence. Because their lives are often highly stressful, people with Type A personalities tend to be at a higher risk for heart disease.

Stress Management and Cardiovascular Health

Many people are beginning to focus on changing unhealthy habits in order to achieve better lives. Diets are being modified, and time is being made for exercise, but countless individuals are neglecting one key aspect of their life: their mental health. Eating a diet low in salt and fat can help lower blood pressure and heart rate, two contributing factors to heart disease. Daily exercise can also keep your heart rate, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels low, lowering your risk for heart disease. However, managing one’s stress levels and finding healthy outlets for stress is a crucial component for preventing cardiovascular disease. Things like yoga, meditation, reducing one’s workload, and taking personal time to relax can reduce stress levels, aid in stress management, and reduce the risk of heart disease.

Source: Boundless. “How the Body Responds to Stress.” Boundless Psychology Boundless, 22 Aug. 2016. Retrieved 2 Mar. 2017 from https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/stress-and-health-psychology-17/stress-and-the-body-87/how-the-body-responds-to-stress-328-12863/

Reading for Race Part 2: The Story We Tell