Introducing Health Psychology

Health psychology is the application of psychological theory and research to health, illness, and healthcare.

Key Points

- Health psychology is concerned with the psychology of a range of health-related behaviors, including healthy eating, the doctor-patient relationship, a patient’s understanding of health information, and beliefs about illness.

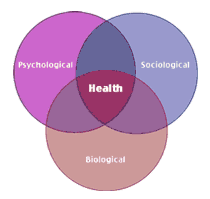

- The biopsychosocial model views health and illness as the product of biological characteristics (genes), behavioral factors (lifestyle, stress, health beliefs), and social conditions (cultural influences, family relationships, social support).

- Clinical health psychology (CIHP) refers to the application of scientific knowledge, derived from the field of health psychology, to clinical questions that may arise across the spectrum of healthcare.

- Public health psychology (PHP) is population oriented, investigating potential causal links between psychosocial factors and health at the population level.

- Community health psychology (CoHP) investigates community factors that contribute to the health and well-being of individuals in their communities.

- Critical health psychology (CrHP) is concerned with the distribution of power and the impact of power differentials on health experience and behavior, healthcare systems, and health policy.

Health psychology, often referred to as behavioral medicine or medical psychology, is the application of psychological theory to health-related practices. The field of health psychology includes two sub-fields. Behavioral health focuses on prevention of health problems and illnesses, while behavioral medicine focuses on treatment. Health psychology is concerned with the psychology of a range of health-related behaviors, including nutrition, exercise, healthcare utilization, and medical decision-making.

Goals of Health Psychology

There are eight major goals of health psychology:

- understanding behavioral and contextual factors for health and illness

- preventing illness

- investigating the effects of disease

- providing critical analyses of health policies

- conducting research on prevention of and intervention in health problems

- improving doctor-patient communication

- improving adherence to medical advice

- finding treatments to manage pain.

Focuses of Health Psychology

Health psychology addresses individual and population-level issues across four domains: clinical, public, community, and critical (social justice).

Clinical Health Psychology

Clinical health psychology refers to the application of scientific knowledge to clinical questions that arise across the spectrum of healthcare. Because it focuses on the prevention and treatment of health problems, clinical health psychology is a specialty practice area for clinical psychologists. Clinical practice includes education on mechanisms of behavior change and psychotherapy.

Public Health Psychology

Public health psychology investigates potential causal links between psychosocial factors and health at the population level. Public health psychologists present research results on epidemiological findings related to health behaviors to educators, policy makers, and health care providers in order to promote public health initiatives for at-risk groups.

Community Health Psychology

Community health psychology investigates community factors that contribute to the health and well-being. Community health psychology also develops community-level interventions that are designed to combat disease and promote physical and mental health. Examples of community health initiatives might be efforts to eliminate soft drinks from schools, diabetes awareness events, etc.

Critical Health Psychology

Critical health psychology is concerned with the distribution of power and the impact of power differentials on health behaviors, healthcare systems, and health policy. Critical health psychology prioritizes social justice and the universal right to good health for people of all races, genders, ages, and socioeconomic positions. A major concern is health inequality, and the critical health psychologist acts as an agent of change working to create equal access to healthcare.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Illness

The Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model views health and illness behaviors as products of biological characteristics (such as genes), behavioral factors (such as lifestyle, stress, and health beliefs), and social conditions (such as cultural influences, family relationships, and social support). Health psychologists work with healthcare professionals and patients to help people deal with the psychological and emotional aspects of health and illness. This can include developing treatment protocols to increase adherence to medical treatments, weight loss programs, smoking cessation, etc. Their research often focuses on prevention and intervention programs designed to promote healthier lifestyles (e.g., exercise and nutrition programs).

Key Points

- According to the biopsychosocial model, it is the deep interrelation of all three factors (biological, psychological, social) that leads to a given outcome—each component on its own is insufficient to lead definitively to health or illness.

- The psychological component of the biopsychosocial model seeks to find a psychological foundation for a particular symptom or array of symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, irritability, overwhelming sadness, etc.).

- Social and cultural factors are conceptualized as a particular set of stressful events (being laid off, for example) that may differently impact the health of people from different social environments and histories.

- Issues to consider with the biopsychosocial model include the degree of influence that each factor has, the degree of interaction between factors, and variation across individuals and life spans.

The biopsychosocial model of health and illness is a framework developed by George L. Engel that states that interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors determine the cause, manifestation, and outcome of wellness and disease. Historically, popular theories like the nature versus nurture debate posited that any one of these factors was sufficient to change the course of development. The biopsychosocial model argues that any one factor is not sufficient; it is the interplay between people’s genetic makeup (biology), mental health and behavior (psychology), and social and cultural context that determine the course of their health-related outcomes.

Biological Influences on Health

Biological influences on health include an individual’s genetic makeup and history of physical trauma or infection. Many disorders have an inherited genetic vulnerability. The greatest single risk factor for developing schizophrenia, for example is having a first-degree relative with the disease (risk is 6.5%); more than 40% of monozygotic twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected. If one parent is affected the risk is about 13%; if both are affected the risk is nearly 50%.

It is clear that genetics have an important role in the development of schizophrenia, but equally clear is that there must be other factors at play. Certain non-biological (i.e., environmental) factors influence the expression of the disorder in those with a pre-existing genetic risk.

Psychological Influences on Health

The psychological component of the biopsychosocial model seeks to find a psychological foundation for a particular symptom or array of symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, irritability, overwhelming sadness, etc.). Individuals with a genetic vulnerability may be more likely to display negative thinking that puts them at risk for depression; alternatively, psychological factors may exacerbate a biological predisposition by putting a genetically vulnerable person at risk for other risk behaviors. For example, depression on its own may not cause liver problems, but a person with depression may be more likely to abuse alcohol, and, therefore, develop liver damage. Increased risk-taking leads to an increased likelihood of disease.

Social Influences on Health

Social factors include socioeconomic status, culture, technology, and religion. For instance, losing one’s job or ending a romantic relationship may place one at risk of stress and illness. Such life events may predispose an individual to developing depression, which may, in turn, contribute to physical health problems. The impact of social factors is widely recognized in mental disorders like anorexia nervosa (a disorder characterized by excessive and purposeful weight loss despite evidence of low body weight). The fashion industry and the media promote an unhealthy standard of beauty that emphasizes thinness over health. This exerts social pressure to attain this “ideal” body image despite the obvious health risks.

Cultural Factors

Also included in the social domain are cultural factors. For instance, differences in the circumstances, expectations, and belief systems of different cultural groups contribute to different prevalence rates and symptom expression of disorders. For example, anorexia is less common in non-western cultures because they put less emphasis on thinness in women.

Culture can vary across a small geographic range, such as from lower-income to higher-income areas, and rates of disease and illness differ across these communities accordingly. Culture can even change biology, as research on epigenetics is beginning to show. Specifically, research on epigenetics suggests that the environment can actually alter an individual’s genetic makeup. For instance, research shows that individuals exposed to over-crowding and poverty are more at risk for developing depression with actual genetic mutations forming over only a single generation.

Application of the Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model states that the workings of the body, mind, and environment all affect each other. According to this model, none of these factors in isolation is sufficient to lead definitively to health or illness—it is the deep interrelation of all three components that leads to a given outcome.

Health promotion must address all three factors, as a growing body of empirical literature suggests that it is the combination of health status, perceptions of health, and sociocultural barriers to accessing health care that influence the likelihood of a patient engaging in health-promoting behaviors, like taking medication, proper diet or nutrition, and engaging in physical activity.

Attitude and Health

Key Points

- Part of health psychology is understanding how psychological factors (such as attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, moods, and emotions) and overall quality of life impact a person’s health.

- Psychological factors may impact our health directly, or they may influence our behaviors, which in turn affect our health in either positive or negative ways.

- Both attitudes and moods (positive or negative) have important implications for health. The kind of attitude we hold about something influences our behavior and our experience of stress; interpreting an event in a negative way is a risk factor for a host of health problems.

- Research indicates that optimism correlates with a lower likelihood of developing certain diseases. Learned helplessness and pessimism, on the other hand, are associated with depression, stress, weakened immune systems, and increased rates of minor and major ailments.

- Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an assessment of how an individual’s well-being may affect, or be affected by, a disease, disability, or disorder. Although causality cannot always be determined, poor quality of life is often correlated with poor health.

- Health is negatively impacted by many aspects of quality of life, such as poverty, poor nutrition, lack of access to education, lack of leisure time, increased stress, and social isolation.

Part of health psychology is understanding how psychological factors (such as attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, moods, and emotions) and overall quality of life impact a person’s health. “Quality of life” refers to the general well-being of individuals and societies, including not only wealth and employment (which are often referred to as “standard of living”), but also the built environment, physical and mental health, education, recreation and leisure time, and social belonging. These factors may impact our health directly, or they may influence our behaviors, which in turn affect our health in either positive or negative ways.

Psychology: Attitudes, Moods, and Our Health

One psychological factor that influences physical health is one’s attitudes. An attitude can be thought of as a positive or negative evaluation of people, objects, event, or ideas.

Attitudes are changeable, they can be formed from a person’s past and present, and they can influence a person’s behavior and well-being. Some attitudes are explicit (i.e., deliberately formed) while others are implicit (i.e., unconscious or outside of awareness). Implicit and explicit attitudes both affect people’s behavior, though in different ways. The kind of attitude we hold about a particular person, event, or idea influences how we behave in relation to it, and, thus, our experience of stress in relation to it. Stress is highly correlated with both physical and mental health, so if we hold a certain attitude toward something that increases our stress level, our health may suffer as a result.

Moods also have important implications for mental and physical health. Negative moods can influence people’s behavior by determining how they interpret and translate the world around them. Interpreting an event in a negative way is a risk factor for a host of mental health problems including depression, anxiety, aggression, poor self-esteem, and physiological stress, all of which negatively impact one’s health and well-being. Positive moods, on the other hand, are thought to increase the likelihood of physical health and well-being by lowering these risk factors.

Attitude and outlook

Research suggests that optimism and positive outlooks are associated with increased health and well-being, while pessimism and learned helplessness decrease health.

Learned Optimism vs. Learned Helplessness

Optimism

Optimism is a world view that interprets situations and events as being optimal, or favorable. Learned optimism refers to the development of one’s potential for this optimized outlook; it is the belief that one can influence the future in tangible and meaningful ways. Research shows that optimism correlates with physical health, including a lower likelihood of cardiovascular disease, stroke, depression, and cancer. It also correlates with emotional health, as optimists are more hopeful, have an increased sense of peace and well-being, and embrace change. Furthermore, optimists have been shown to live healthier lifestyles (i.e., smoking less, being more physically active, consuming healthier foods, and consuming more moderate amounts of alcohol) and utilize more positive coping mechanisms, both of which may lower the risk of disease.

Explanatory Style

Life or world outlooks have three general dimensions: internal vs. external, stable vs. unstable, and global vs. specific. In general, people with an optimistic outlook believe that negative experiences can be attributed to factors outside of the self (external), are not likely to occur consistently (unstable), and are limited to domains or circumstances (specific). They believe the exact opposite in regards to positive experiences, such that these are a result of the self (internal), expected to be repeated (stable), and broadly applicable to life (global). Optimists view the world as constantly working in their favor—even when physical or personal circumstances would seem otherwise. In this way, they are better equipped mentally to handle setbacks in everyday life, as these are believed to be momentary. They are also more likely to embrace and build upon positive circumstances and situations, as these are expected to continue.

Pessimism

In contrast, learned helplessness is the belief that one has no control over the events in one’s life. Learned helplessness is associated with depression and anxiety, both of which threaten a person’s physical and mental well-being; it can also contribute to poor health when people neglect diet, exercise, and medical treatment, falsely believing they have no power to change. The more people perceive events as uncontrollable, the more stress they experience, and the less hope they feel about making changes in their lives. Related to this, research has shown that people with a pessimistic explanatory style are more likely to suffer from depression and stress, have weakened immune systems, be more vulnerable to minor ailments (like a cold or fever) and major illnesses (such as heart attacks or cancer), and have a less effective recovery from health problems.

Quality of Life

Quality of life is recognized as an increasingly important healthcare topic. In general, quality of life is a person’s assessment of their well-being, or lack thereof. This includes all emotional, social, and physical aspects of the individual’s life. In healthcare, health-related quality of life is an assessment of how the individual’s well-being may affect, or be affected by, a disease, disability, or disorder.

Internal Influences

An individual’s perceived quality of life is often influenced by their personal expectations, which can vary over time based on environmental influences. Perceived quality of life is highly subjective, and patients’ and physicians’ rating of the same objective situation have been found to differ significantly. Patient questionnaires assessing quality of life are often multidimensional and cover physical, social, emotional, cognitive, work- or role-related, and possibly spiritual aspects, and even the financial impact of medical conditions. Although causality cannot always be determined, poor quality of life is often correlated with poor health, and high quality of life is often correlated with better health.

External Influences

Living conditions, nutrition, access to education, leisure time, and social isolation are all aspects of quality of life that have been shown to impact a person’s health. Poverty is one aspect that is particularly significant—in fact, one third of deaths (around 18 million people a year) are due to poverty-related causes; in total 270 million people, most of them women and children, have died as a result of poverty since 1990. Those living in poverty lack access to basic resources such as healthcare, food, and housing, and suffer disproportionately from malnutrition, disease, lower life expectancy, and disability. Poverty has also been shown to directly impede cognitive function due to the severe burden on one’s mental resources brought about by financial worries.

Bandura’s and Rotter’s Social-Cognitive Theories

Key Points

- Social-cognitive theories of personality emphasize the role of cognitive processes, such as thinking and judging, in the development of personality.

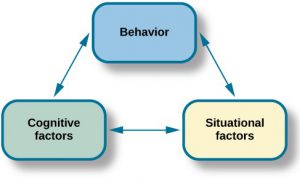

- Albert Bandura is a behavioral psychologist who came up with the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behavior, and context all interact with and influence each other.

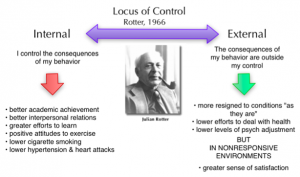

- Rotter expanded upon on Bandura’s ideas and developed the term locus of control to describe our beliefs about the power we have over our lives.

- A person with an internal locus of control believes that their rewards in life are guided by their own decisions and efforts. If they do not succeed, they believe it is due to their own lack of effort.

- A person with an external locus of control believes that rewards or outcomes are determined by luck, chance, or other people with more power than them. If they do not succeed, they believe it is due to forces outside of their control.

Social-cognitive theories of personality emphasize the role of cognitive processes, such as thinking and judging, in the development of personality. Social cognition is basically social thought, or how the mind processes social information; social-cognitive theory describes how individuals think and react in social situations. How the mind works in a social setting is extremely complicated—emotions, social desirability factors, and unconscious thoughts can all interact and affect social cognition in many ways. Two major figures in social cognitive-theory are behaviorist Albert Bandura and clinical psychologist Julian Rotter.

Albert Bandura (1925-present)

Albert Bandura is a behavioral psychologist credited with creating social learning theory. He agreed with B.F. Skinner’s theory that personality develops through learning; however, he disagreed with Skinner’s strict behaviorist approach to personality development. In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behavior, Bandura (1990) proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behavior, and context all interact, each factor simultaneously influencing and being influenced by the others. Cognitive processes refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations, and personality characteristics. Behavior refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behavior occurs refers to the environment or situation, which includes rewarding/punishing stimuli.

This theory was significant because it moved away from the idea that environment alone affects an individual’s behavior. Instead, Bandura hypothesized that the relationship between behavior and environment was bi-directional, meaning that both factors can influence each other. In this theory, humans are actively involved in molding the environment that influences their own development and growth.

Reciprocal determinism

Bandura proposed the idea of reciprocal determinism, in which our behavior, cognitive processes, and situational context all influence each other.

Julian Rotter (1916-present)

Julian Rotter is a clinical psychologist who was influenced by Bandura’s social learning theory after rejecting a strict behaviorist approach. Rotter expanded upon Bandura’s ideas of reciprocal determinism, and he developed the term locus of control to describe how individuals view their relationship to the environment. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives, and is a cognitive factor that affects personality development. Locus of control can be classified along a spectrum from internal to external; where an individual falls along the spectrum determines the extent to which they believe they can affect the events around them.

Locus of control

Rotter’s theory of locus of control places an individual on a spectrum between internal and external.

Internal Locus of Control

A person with an internal locus of control believes that their rewards in life are guided by their own decisions and efforts. If they do not succeed, they believe it is due to their own lack of effort. An internal locus of control has been shown to develop along with self-regulatory abilities. People with an internal locus of control tend to internalize both failures and successes.

Many factors have been associated with an internal locus of control. Males tend to be more internal than females when it comes to personal successes—a factor likely due to cultural norms that emphasize aggressive behavior in males and submissive behavior in females. As societal structures change, this difference may become minimized. As people get older, they tend to become more internal as well. This may be due to the fact that as children, individuals do not have much control over their lives. Additionally, people higher up in organizational structures tend to be more internal. Rotter theorized that this trait was most closely associated with motivation to succeed.

External Locus of Control

A person with an external locus of control sees their life as being controlled by luck, chance, or other people—especially others with more power than them. If they do not succeed, they believe it is due to forces outside their control. People with an external locus of control tend to externalize both successes and failures. Individuals who grow up in circumstances where they do not see hard work pay off, as well as individuals who are socially disempowered (such as people in a low socioeconomic bracket), may develop an external locus of control. An external locus of control may relate to learned helplessness, a behavior in which an organism forced to endure painful or unpleasant stimuli becomes unable or unwilling to avoid subsequent encounters with those stimuli, even if they are able to escape.

Evidence has supported the theory that locus of control is learned and can be modified. However, in a non-responsive environment, where an individual actually does not have much control, an external locus of control is associated with a greater sense of satisfaction.

Examples of locus of control can be seen in students. A student with an internal locus of control may receive a poor grade on an exam and conclude that they did not study enough. They realize their efforts caused the grade and that they will have to try harder next time. A student with an external locus of control who does poorly on an exam might conclude that the test was poorly written and the teacher was incompetent, thereby blaming external factors out of their control.

The Experience of Illness

Key Points

- Some scholars have maintained a distinction between illness and disease by describing illness as a patient’s subjective perception of an objectively defined disease.

- Epidemiology is the scientific study of factors affecting the health and illness of individuals and population.

- Behavioral medicine is an interdisciplinary field of medicine concerned with the development and integration of psychosocial, behavioral, and biomedical knowledge relevant to health and illness.

- The rise of scientific medicine in the past two centuries has altered or replaced many historic health practices.

- Mental illness is a broad generic label for a category of illnesses that may include affective or emotional instability, behavioral dysregulation, and/or cognitive dysfunction or impairment.

Introduction to Illness

Illness, sometimes considered another word for disease, is a state of poor health. Some scholars have maintained a distinction by describing illness as a patient’s subjective perception of an objectively defined disease. Conditions of the body or mind that cause pain, dysfunction, or distress can be deemed an illness. Sometimes the term is used broadly to include injuries, disabilities, syndromes, infections, symptoms, deviant behaviors, and atypical variations of structure and function. In other contexts these may be considered distinguishable categories.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the scientific study of factors affecting the health and illness of individuals and populations; it serves as the foundation and logic for interventions made in the interest of public health and preventive medicine. Behavioral medicine is an interdisciplinary field of medicine concerned with the development and integration of psychosocial, behavioral, and biomedical knowledge relevant to health and illness. According to evolutionary medicine, much illness is not directly caused by an infection or body dysfunction, but is instead a response created by the body. Fever, for example, is not caused directly by bacteria or viruses but by the body raising its normal temperature, which some people believe inhibits the growth of the infectious organism. Evolutionary medicine calls this set of responses “sickness behavior. ”

All human societies have beliefs that provide explanations for, and responses to, childbirth, death, and disease. Throughout the world, illness has often been attributed to witchcraft, demons, or the will of the gods—ideas that retain some power within certain cultures and communities. However, the rise of scientific medicine in the past two centuries has altered or replaced many historic health practices.

Mental illness is a broad category of illnesses that may include affective or emotional instability, behavioral dysregulation, and/or cognitive dysfunction or impairment. Specific illnesses known as mental illnesses include major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, to name a few.

Statistics show that more and more people are being diagnosed with mental disorders. The National Institute for Mental Health reports that over 40 million adults are diagnosed with an anxiety disorder in a given year, accounting for 18 percent of the population. Other disorders that are prevalent are ADHD (4 percent), mood disorders (9.5 percent) and and autism (1 percent, but quickly rising)

Preventing Illness

Key Points

- Preventive care may include examinations and screening tests tailored to an individual’s age, health, and family history.

- Preventive medicine or preventive care refers to measures taken to prevent diseases rather than curing them or treating their symptoms.

- Professionals involved in the public health aspect of this practice may be involved in entomology, pest control, and public health inspections.

- Intrauterine devices (IUD) are highly effective and highly cost effective contraceptives, however where universal health care is not available the initial cost may be a barrier.

Preventive medicine, or preventive care, refers to measures taken to prevent diseases, rather than curing them or treating their symptoms. The term contrasts in method with curative and palliative medicine, and in scope with public health methods, which work at the level of population health rather than individual health. Simple examples of preventive medicine include hand washing, breastfeeding, and immunizations. Preventive care may include examinations and screening tests tailored to an individual’s age, health, and family history. For example, a person with a family history of certain cancers or other diseases would begin screening at an earlier age and/or more frequently than those with no such family history.

Professionals involved in the public health aspect of this practice may be involved in entomology, pest control, and public health inspections. Public health inspections can include recreational waters, swimming pools, beaches, food preparation and serving, and industrial hygiene inspections and surveys.

Since preventive medicine deals with healthy individuals or populations, the costs and potential harms from interventions need even more careful examination than in treatment. For an intervention to be applied widely it generally needs to be affordable and highly cost effective. For instance, intrauterine devices (IUD) are highly effective and highly cost effective contraceptives, however where universal health care is not available the initial cost may be a barrier. Preventive solutions may be less profitable and therefore less attractive to makers and marketers of pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Birth control pills, which are taken every day and may take in a thousand dollars over ten years, may generate more profits than an IUD, which despite a huge initial markup only generates a few hundred dollars over the same period.

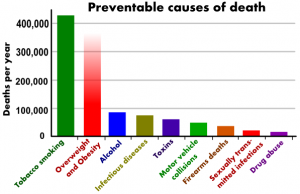

Leading Preventable Causes of Death in the United States.

This data is outdated and was in fact significantly revised in subsequent reports of the leading causes of deaths, especially for obesity-related diseases.

Health Behaviors

Nutrition and Health

Key Points

- Food is fuel for the body. Cells use nutrients from food to sustain cellular functioning.

- Nutritional requirements include macronutrients (such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats), and micronutrients (such as vitamins, minerals, and amino and fatty acids) in order to maintain proper function.

- Malnutrition is caused by both excess food consumption and insufficient food consumption. Both can result in disease and disorders within the body and mind.

Human Nutrition and Health

From Hippocrates’ classic line “let food be your medicine, and medicine be your food,” to the popular modern warning that “you are what you eat,” humans have always understood the connection between nutrition and health. The key to understanding why food has such an impact on overall health lies in the physiological needs of human cells. Cells rely on nutrients in food to function properly. Problems like disease and disability occur when the body receives inadequate nutrition.

Needs of the Body

In order to function properly, the human body must meet specific caloric and nutritional needs.

Caloric needs

Caloric needs refer to the energy required to carry out various chemical reactions within each cell of the body. The body gets energy from macronutrients—the fats, carbohydrates, and proteins in the food we eat. These molecules are broken down into essential amino acids and fatty acids and used as fuel for cellular functions. The number of calories a person requires per day varies based on an individual’s age, sex, height, and physical activity. If excess caloric energy is consumed, beyond what is needed to maintain body functioning, it is stored in adipose (fat) tissue.

Nutritional needs

Along with its need for energy from macronutrients, the body requires a variety of micronutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, to support tissue growth, enzyme structure, and cellular functions. These can be found in a variety of fruits, vegetables, fibers, and water.

The Basics of Nutrition: Macronutrients, Amino and Fatty Acids, and Micronutrients

Macronutrients

Macronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Carbohydrates produce necessary metabolic energy for the body. Fiber is an important carbohydrate that is often implicated in disease prevention, as increases in fiber have been found to correlate with decreases in colon cancer, heart disease, and adult-onset diabetes.

Amino and Fatty acids

Amino acids are organic compounds primarily composed of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon. Proteins are made up of chains of amino acids connected by peptide bonds; they form hormones, enzymes, and antibodies within the human body. There are twenty standard amino acids, nine of which are essential and must be obtained from food.

Fats, or lipids, are combinations of fatty acids. Although it is often vilified, fat serves a vital function in the body, serving as stored energy, protecting organs, and helping to regulate body temperature. Fats are classified as saturated (generally bad) and unsaturated (generally good), depending on the structure of fatty acids involved. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids are particularly important in maintaining health, while trans fatty acids have been found to harm body function.

Micronutrients

Micronutrients include dietary vitamins and minerals which are necessary to sustain health. Supplements can be used to make up for not getting enough micronutrients from diet alone. Vitamin deficiencies may result in physical dysfunction, including impaired immune function, premature aging, and even poor psychological health. The benefits of trace minerals range from bone and tooth formation to acid-base balance.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition refers to insufficient, excessive, or imbalanced consumption of nutrients. In developed countries, this often occurs in the form of overconsumption of sugary, nutrient-deficient food, which is linked to obesity and numerous related health conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. In the developing world, where access to food is often compromised, malnutrition often manifests as hunger, starvation, and malnourishment. Chronic malnourishment prevents healthy growth and impairs vital body functions; this leads to physical health problems and, eventually, death. Consequently, one of the best things a person can do to promote overall health and wellness is to maintain adequate nutrition.

Psychological impact of nutrition deficiency

There is a reciprocal relationship between the physical and psychological effects of poor nutrition. While malnutrition refers to physical impairments resulting from a poor diet, the underlying nutritional deficiencies can have significant impact on mental well-being (including perception and judgment), and often exacerbate existing psychological disorders. Existing or incipient psychological conditions (e.g. eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia) can cause nutritional deficiency and result in poor physical health.

Exercise and Health

Key Points

- Physical exercise is any activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and mental function.

- Exercise can come in many forms but usually falls into one of three types: flexibility (affects joint mobility), aerobic (affects cardiovascular function), and anaerobic (affects muscle strength).

- The benefits 0f exercise for the body include weight maintenance, injury and disease prevention, and improved functioning.

- The benefits from exercise for the mind include higher levels of endorphins, which elevate the body to a state of euphoria, and mastery, which promotes self-esteem and improved mood.

Managing Health Through Exercise

Exercise is any activity that requires physical effort and is carried out with the goal of sustaining or improving physical fitness. Exercise has many benefits for the body and mind: protecting against injury, improving cardiovascular function, honing athletic skills, managing weight, boosting the immune system, counteracting depression, and elevating mood.

Types of Exercise

Physical exercise can be classified into three primary types based on the overall effect the exercise has on the body: flexibility, aerobic, and anaerobic. Flexibility exercise challenges the body’s range of motion through stretching, bending, and balance movements. Aerobic exercise increases cardiovascular capacity through activities like running, biking, or swimming. Anaerobic exercise improves muscle strength through weight training. Exercises can also be classified as dynamic when they involve active or flowing movement (like running or yoga), or static when they involve isolated poses or movements (such as weight-lifting or holding stretches). Certain exercises may have aerobic, anaerobic, and flexibility benefits. Calesthenics, for example, which includes rhythmic gross motor movements and strengthening exercise that use only body weight as resistance (e.g., jumping jacks, push ups, sit ups, etc.) increase aerobic and muscular conditioning, agility, and coordination.

Effects of Exercise on the Body

All of these types of physical exercise contribute to physical fitness. Body weight and composition is maintained by a combination of the food we consume and the energy we expend throughout the day. Physical activity increases the amount of energy the body needs to function. The more exercise a person does, the more energy the body uses. As a result, fewer calories are stored in the form of fat, and this translates into either weight maintenance or weight loss. Along with healthy body weight, exercise has other physical health benefits. It increases cardiovascular functioning, which reduces the risk for certain diseases like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. Exercise can also positively affect bone density, muscle strength, and joint mobility. Strong bodies have reduced surgical risks, better immune function, and lower susceptibility to illness and infection.

Exercise also serves as stress relief, which has both physiological and psychological benefits. Research shows that exercise reduces cortisol levels, a hormone that is released when the body is stressed and has been shown to have negative health consequences (including heart disease and depression) when chronically elevated. The brain also benefits from physical exercise through increases in blood flow and oxygen that promote cell generation and proliferation. In general, a steady practice of exercise keeps the body strong and functioning properly.

Effects of Exercise on the Mind

Research shows that physical exercise also plays an important role in promoting mental health. Exercise increases levels of endorphins in the body. These naturally occurring opioids are the body’s own pain killers. They work in conjunction with neurotransmitters to induce relief, happiness, or even euphoria when the body is in pain or overexerted. Marathon runners will often experience what is called a “runner’s high;” this can allow them to continue running despite the physical exhaustion they might feel. Research shows that exercise elevates levels of serotonin and endorphins and that these elevations remain for several days after exercise, contributing to a lasting improvement in mood. Exercise has been proven to have positive effects on people suffering from depression, and promotes positive levels of self-esteem. This phenomenon is due not only to the chemicals involved, but also results from the positive body-image and feeling of competence that come with accomplishing a fitness goal.

Substance Abuse and Health

Learning Objective

- Describe the psychological and physical effects of substance abuse

Key Points

- Substance abuse is the habitual use of drugs in dangerous amounts or situations. Both legal and illegal drugs can be used in a harmful manner.

- Extended drug use can lead to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal.

- Extended abuse of substances can cause detrimental physical and mental effects including heart, liver, and cognitive problems as well as depression, anxiety, and psychosis.

- Substance abuse is associated with higher rates of suicide.

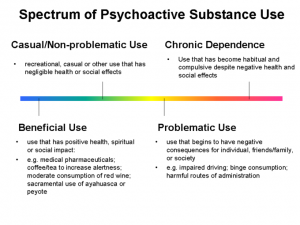

Substance abuse is the habitual and recreational use of an addictive agent (drug) that is consumed in dangerous amounts or dangerous situations. The psychoactive effects of drug abuse occur when the drugs impact the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain that control normal mental and physical functioning. For instance, chronic drug abuse can negatively impact memory functioning, impulse control, and reaction time; it can also increase the risk for heart disease, cancer, liver failure, etc. Individuals who use substances to the point of dependence are at even greater risk for physical health problems, or even overdose, due to development of tolerance, or needing to use more and more of the substance to obtain the desired effect. Withdrawal symptoms are equally dangerous: these are the uncomfortable and sometimes fatal physical symptoms that occur when the drug is absent from the body.

Psychological Effects of Substance Abuse

Substance abuse can have a notable adverse effect on mood, increase the risk of mental illness, and exacerbate preexisting symptoms. Some people turn to substances to self-medicate for disorders like depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder, only to find that substance use, while diminishing psychological distress in the short-term, only exacerbates the symptoms in the long run. Even worse is that the negative psychological side effects of substance use put abusers at a increased risk of suicide. Some substances can induce mood, anxiety, or psychotic symptoms, and these symptoms may persist even after the effects of the drug have subsided. In some cases hallucinogens like mescaline and peyote have triggered psychotic behaviors that last for years after use.

Physical Effects of Substance Abuse

In addition to adversely altering the mental health of users, substance abuse can have a significant and long-lasting impact on the body. Short term effects can manifest in the form of drowsiness and changes in breathing (slow breathing or hyperventilation), abdominal cramping, diarrhea, irregular heart rate, and even strokes. In the long term, users may suffer from dental and gum deterioration, sleep disorders, a variety of respiratory problems, and damage to the brain, kidneys, and liver. Users may also lose their appetite and their ability to regulate body temperature.

Substance abuse can also lead to secondary physical effects. A user’s mental state may cause them to take unnecessary risks or engage in self harm or aggressive behavior toward others. Another array of secondary (physical) effects manifests if the user stops taking regular doses of the substance. This is often called “withdrawal” and can result in uncontrollable shaking and convulsions, extreme physical pain, and even dehydration, since users in this state may be unable to consume food and water. Yet another set of secondary effects stems from the unhealthy conditions in which substances are often consumed: for instance, sharing or using unsterilized needles can cause users to contract AIDS, hepatitis, or other diseases.

Stages of Changing Health Behaviors

Key Points

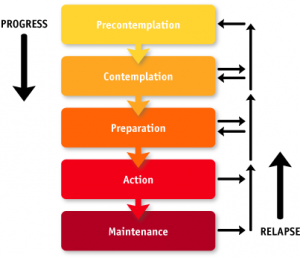

- Created by Prochaska and DiClemente in the 1970s, the transtheoretical model (also called the stages-of-change model) proposes that change is not a discrete decision, but is instead a five-step process that consists of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

- At the precontemplation stage, an individual may or may not be aware of a problematic behavior, and generally has no desire to change their behavior.

- At the contemplation stage, participants are intending to start the healthy behavior but are still ambivalent.

- People at the preparation stage are ready to start taking action, and take small steps that they believe can help them make the healthy behavior a part of their lives.

- In the action stage, people have changed their behavior and need to work hard to keep moving ahead. An individual finally enters the maintenance stage once they exhibit the new behavior consistently for over six months.

- Despite the stress caused by their problem behavior, many people simply are not ready to initiate change; the stages-of-change model helps assess where on the spectrum they fall and to guide treatment efforts accordingly.

The Process of Change

Because health psychology is interested in the psychology behind health-related behaviors, it also concerns itself with how people can learn to change their behaviors. The transtheoretical model of behavior change assesses an individual’s readiness to act on a new healthier behavior, and provides strategies to guide the individual through each stage of the behavior-change process.

Created by Prochaska and DiClemente in the 1970s, the model proposes that change is a process rather than a discrete decision. People must build up the motivation to change and this motivation is dependent on a number of personal and environmental factors. According to the transtheoretical model, behavioral change is a five-step process, consisting of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

Precontemplation

At the precontemplation stage, an individual may or may not be aware of a problematic behavior, and generally has no desire to change their behavior. People in this stage learn more about healthy behavior: they are encouraged to think about the benefits of changing their behavior and to feel emotions about the effects of their negative behavior on others. Precontemplators typically underestimate the pros of changing and overestimate the cons. One of the most effective steps that others can help with at this stage is to encourage them to become more mindful of their decision making and more conscious of the multiple benefits of changing an unhealthy behavior.

Contemplation

At this stage, participants are intending to start the healthy behavior, often within the next six months. While they are usually more aware of the pros of changing, their cons are about equal to their pros. This ambivalence about changing can cause them to keep putting off taking action. People in this stage learn about the kind of people they could be if they changed their behavior and learn more from people who behave in healthy ways. Others can help people at this stage by encouraging them to work on reducing the cons of changing their behavior.

Preparation

People at this stage are ready to start taking action, generally within the next 30 days. They take small steps that they believe can help them make the healthy behavior a part of their lives, such as telling their friends and family. People in this stage should be encouraged to seek support, tell people about their plan to change, and think about how they would feel if they behaved in a healthier way. Their main concern is this: When they act, will they fail? They learn that the better prepared they are, the more likely they are to keep progressing.

Action

In the action stage, people have changed their behavior and need to work hard to keep moving ahead. These participants need to learn how to strengthen their commitments to change and to fight urges to slip back. Useful techniques at this stage can include substituting activities related to the unhealthy behavior with positive ones, rewarding themselves for taking steps toward changing, and avoiding people and situations that tempt them to behave in unhealthy ways.

Maintenance

An individual finally enters the maintenance stage once they exhibit the new behavior consistently for over six months. It is important for people in this stage to be aware of situations that may tempt them to slip back into doing the unhealthy behavior—particularly stressful situations. It is recommended that people in this stage seek support from and talk with people they trust, spend time with people who behave in healthy ways, and remember to engage in healthy activities to cope with stress instead of relying on unhealthy behavior.

Some theorists suggest a sixth phase called termination, in which individuals have no temptation to return to old unhealthy behaviors as a way of coping. Importantly, the progression through these stages is not strictly linear. People may move back and forth between the stages as their motivation changes. Often people relapse in their behavior multiple times before finally achieving maintenance. In this way, relapse is conceptualized as a return from the action or maintenance stage to an earlier stage.

Applying the Stages of Change

The stages-of-change model has been widely utilized in the treatment of health-related behaviors such as substance use, obesity, diabetes, and other problem behaviors. Change is a difficult process that requires close analysis of the benefits and costs of the behavior. For instance, a smoker must come to the conclusion that the health risks associated with their smoking are more important to them than the benefits, which may include taste, stress relief, social aspects, or other factors. Coming to this decision is no easy task; despite the stress caused by their problem behavior, many people simply are not ready to initiate change. This model helps assess where on the spectrum a person falls and helps guide treatment efforts accordingly.

Identity Roles and Health

Gender and Health

Key Points

- The World Health Organization defines gender as the result of socially constructed ideas about the behavior, actions, and roles a particular sex performs.

- Gender, and particularly the role of women, is widely recognized as vitally important to international development issues.

- Women’s dual responsibilities as caregivers and income earners leaves them suffering from time poverty, and thus unable to access health and education services.

- The Gender-related Development Index (GDI), developed by the United Nations, aims to show the inequalities between men and women in the following areas: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

- The Gender-related Development Index (GDI), developed by the United Nations, aims to show the inequalities between men and women in the following areas: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

The Role of Gender in Health

Gender is a range of characteristics used to distinguish between male and female humans, particularly in the cases of men and women and the masculine and feminine attributes assigned to them. Depending on the context, the discriminating characteristics vary, from sex to social role to gender identity. The World Health Organization defines gender as the result of socially constructed ideas about the behavior, actions, and roles a particular sex performs. Assigning gender involves taking into account the physiological and biological attributes assigned by nature followed by socially constructed conduct. The social label of being classified into one or the other sex is obligatory to the medical stamp on the birth certificate.

There are a number of ways in which health disparities play out based on different systems of stratification. Researchers also find health disparities based on gender stratification. One study found that women are less likely than men to be recommended for knee replacement surgery, even when they have the same symptoms. While it was unclear what role the sex of the recommending physicians played, the authors of this study encouraged women to challenge their doctors in order to get care equivalent to men.

Gender, and particularly the role of women, is widely recognized as vitally important to international development issues. This often means a focus on gender-equality, ensuring participation, but includes an understanding of the different roles and expectations of the genders within the community. As recognized by the United Nations, women’s dual responsibilities as caregivers and income earners leaves them suffering from time poverty, and thus unable to access health and education services. The Gender-related Development Index (GDI), developed by the United Nations, aims to show the inequalities between men and women in the following areas: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

Race and Health

Key Points

- Race and health research, often done in the United States, has found both current and historical racial differences in the frequency, treatments, and availability of treatments for several diseases.

- In multiracial societies such as the United States, racial groups differ greatly in regard to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, healthcare, and education.

- There is a controversy regarding race as a method for classifying humans. The continued use of racial categories has been criticized.

- Apart from the general controversy regarding race, some argue that the continued use of racial categories in health care, and as risk factors, could result in increased stereotyping and discrimination in society and health services.

The Role of Race in Health

Health disparities refer to gaps in the quality of health and healthcare across racial and ethnic groups. Race and health research, often done in the United States, has found both current and historical racial differences in the frequency, treatments, and availability of treatments for several diseases. This can add up to significant group differences in variables such as life expectancy. Many explanations for such differences have been argued, including socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, social environment, and access to preventive health-care services, among other environmental differences.

In multiracial societies such as the United States, racial groups differ greatly in regard to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, healthcare, diet, and education. There is also the presence of racism which some see as a very important explaining factor. Some argue that for many diseases racial differences would disappear if all environmental factors could be controlled for. Race-based medicine is the term for medicines that are targeted at specific ethnic clusters, which are shown to have a propensity for a certain disorder. Critics are concerned that the trend of research on race specific pharmaceutical treatments will result in inequitable access to pharmaceutical innovation, and smaller minority groups may be ignored.

Health disparities based on race also exist. Similar to the difference in life expectancy found between the rich and the poor, affluent white women live 14 years longer in the U.S. (81.1 years) than poor black men (66.9 years). There is also evidence that blacks receive less aggressive medical care than whites, similar to what happens with women compared to men. Black men describe their visits to doctors as stressful, and report that physicians do not provide them with adequate information to implement the recommendations they are given.

Another contributor to the overall worse health of blacks is the incident of HIV/AIDS; the rate of new AIDS cases is ten times higher among blacks than whites, and blacks are 20 times as likely to have HIV/AIDS as are whites. Health disparities are well documented in minority populations such as African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos. When compared to European Americans, these minority groups have higher incidence of chronic diseases, higher mortality, and poorer health outcomes. Minorities also have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and infant mortality than whites. American ethnic groups can exhibit substantial average differences in disease incidence, disease severity, disease progression, and response to treatment.

Infant mortality is another place where racial disparities are quite evident. In fact, infant mortality rates are 14 of every 1000 births for black, non-Hispanics compared to 6 of every 1000 births for whites. Another disparity is access to health care and insurance. In California, more than half (59 percent) of Hispanics go without health care. Also, almost 25 percent of Latinos do not have health insurance, as opposed to 10 percent of Whites.

There is a controversy regarding race as a method for classifying humans. The continued use of racial categories has been criticized. Apart from the general controversy regarding race, some argue that the continued use of racial categories in health care, and as risk factors, could result in increased stereotyping and discrimination in society and health services. There is general agreement that a goal of health-related genetics should be to move past the weak surrogate relationships of racial health disparity and get to the root causes of health and disease. This includes research which strives to analyze human genetic variation in smaller groups across the world.

Social Class and Health

Key Points

- While gender and race play significant factors in explaining healthcare inequality in the United States, socioeconomic status is the greatest determining factor in an individual’s level of access to healthcare.

- Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions, and their distribution among the population, that influence individual and group differences in health status.

- They are risk factors found in one’s living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power), rather than individual factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence the risk for a disease, injury, or vulnerability to disease or injury.

- Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions, and their distribution among the population, that influence individual and group differences in health status.

- Health inequality is the term used in a number of countries to refer to those instances whereby the health of two demographic groups (not necessarily ethnic or racial groups) differs despite comparative access to health care services.

The Role of Social Class in Health

A person’s social class has a significant impact on their physical health, their ability to receive adequate medical care and nutrition, and their life expectancy. While gender and race play significant factors in explaining healthcare inequality in the United States, socioeconomic status is the greatest determining factor in an individual’s level of access to healthcare.

Individuals of lower socioeconomic status in the United States experience a wide array of health problems as a result of their economic status. They are unable to use health care as often, and when they do it is of lower quality, even though they generally tend to experience a much higher rate of health issues. Furthermore, individuals of lower socioeconomic status have less education and often perform jobs without significant health and benefits plans, whereas individuals of higher standing are more likely to have jobs that provide medical insurance. Consequently, they have higher rates of infant mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and disabling physical injuries.

Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions, and their distribution among the population, that influence individual and group differences in health status. They are risk factors found in one’s living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power), rather than individual factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence the risk for a disease, injury, or vulnerability to disease or injury. According to some viewpoints, these distributions of social determinants are shaped by public policies that reflect the influence of prevailing political ideologies of those governing a jurisdiction.

Health inequality is the term used in a number of countries to refer to those instances whereby the health of two demographic groups (not necessarily ethnic or racial groups) differs despite comparative access to health care services. Such examples include higher rates of morbidity and mortality for those in lower occupational classes than those in higher occupational classes, and the increased likelihood of those from ethnic minorities being diagnosed with a mental health disorder.

Education and Health

Key Points

- Health literacy is of continued and increasing concern for health professionals, as it is a primary factor behind health disparities.

- While problems with health literacy are not limited to minority groups, the problem can be more pronounced in these groups than in whites due to socioeconomic and educational factors.

- Reading level, numeracy level, language barriers, cultural appropriateness, format and style, sentence structure, use of illustrations, scope of intervention, and numerous other factors will affect how easily health information is understood and followed.

- The mismatch between a clinician’s level of communication and a patient’s ability to understand can lead to medication errors and adverse medical outcomes.

- Health care professionals (doctors, nurses, public health workers) can also have poor health literacy skills, such as a reduced ability to clearly explain health issues to patients and the public.

- The eHealth literacy model is also referred to as the Lily model. This model includes basic literacy, computer literacy, information literacy, media literacy, science literacy, and health literacy.

Health literacy is an individual’s ability to read, understand, and use healthcare information to make decisions and follow instructions for treatment. Health literacy is of continued and increasing concern for health professionals, as it is a primary factor behind health disparities. While problems with health literacy are not limited to minority groups, the problem can be more pronounced in these groups than in whites due to socioeconomic and educational factors.

There are many factors that determine the health literacy level of health education materials or other health interventions. Reading level, numeracy level, language barriers, cultural appropriateness, format and style, sentence structure, use of illustrations, scope of intervention, and numerous other factors will affect how easily health information is understood and followed. The mismatch between a clinician’s level of communication and a patient’s ability to understand can lead to medication errors and adverse medical outcomes. The lack of health literacy affects all segments of the population, although it is disproportionate in certain demographic groups, such as the elderly, ethnic minorities, recent immigrants and persons with low general literacy. Health literacy skills are not only a problem in the public. Health care professionals (doctors, nurses, public health workers) can also have poor health literacy skills, such as a reduced ability to clearly explain health issues to patients and the public.

Due to the increasing influence of the internet for information-seeking and health information distribution purposes, eHealth literacy has become an important topic of research in recent years. The eHealth literacy model is also referred to as the Lily model, which incorporates the following literacies, each of which are instrumental to the overall understanding and measurement of eHealth literacy: basic literacy, computer literacy, information literacy, media literacy, science literacy, health literacy.

Women in Medicine

Key Points

- Women’s informal practice of medicine in the role of caregivers and in the allied health professions has been widespread.

- The practice of medicine remains disproportionately male overall. In industrialized nations, the recent parity in gender of medical students has not yet trickled into parity in practice.

- Most countries now guarantee equal access by women to medical education. However, not all ensure equal employment opportunities, and gender parity has yet to be achieved within the medical specialties around the world.

The Role of Women in Medicine

Historically and in many parts of the world, women’s participation in medicine (as physicians, for instance) has been significantly restricted, although women’s informal practice of medicine in the role of caregivers and in the allied health professions has been widespread. Most countries of the world now guarantee equal access by women to medical education, although not all ensure equal employment opportunities. Gender parity has yet to be achieved within the medical specialties around the world.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century in industrialized nations, women have made significant gains, but have yet to achieve parity throughout the medical profession. Women’s participation in medical professions was limited by law and practice during the decades while medicine was professionalizing. However, women kept practicing medicine in the allied health fields (nursing, midwifery), making significant gains in medical education and medical work during the 19th and 20th centuries. Women continue to dominate nursing in the 20th century. In 2000, 94.6% of registered nurses in the United States were women.

The practice of medicine remains disproportionately male overall. In some industrialized nations, women have achieved parity in medical school. Since 2003, women have formed the majority of the U.S. medical student body. However, they have yet to achieve parity in practice. In many developing nations, neither medical school nor practice approach gender parity. Moreover, there are skews within the medical profession. For example, some medical specialties like surgery are significantly male-dominated, while other specialties are or becoming significantly female-dominated.

Monique Frize, née Aubry (born 1942) is a Canadian academic and biomedical engineer known for her expertise in medical instrumentation and decision-support systems

At the beginning of the 21st century, women in industrialized nations have made significant gains, but have yet to achieve parity throughout the medical profession. In some industrialized countries, women have achieved parity in medical school. Women have formed the majority of the United States medical student body since 2003. In 2007-2008, women accounted for 49% of medical school applicants and 48.3% of those accepted. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) 48.3% (16,838) of medical degrees awarded in the US in 2009-10 were earned by women, an increase from 26.8% in 1982-3.

Perspectives and Orientations for Understanding

The Conflict Perspective

Key Points

- Conflict theories are perspectives in social science that emphasize the social, political, or material inequality of a social group.

- Of the classical founders of social science, conflict theory is most commonly associated with Karl Marx, who posited that capitalism would inevitably produce internal tensions leading to its own destruction.

- Marx advocated for the rejection of false consciousness (explanations of social problems as the shortcomings of individuals rather than the flaws of society) and the claiming of class consciousness (workers’ recognition of themselves as a class unified in opposition to the capitalist system).

- The Polish-Austrian sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz and the American sociologist Lester F. Ward approached conflict from a comprehensive anthropological and evolutionary point-of-view.

- C. Wright Mills has been called the founder of modern conflict theory. In Mills’s view, social structures are created through conflict between people with differing interests and resources.

- Conflict theory is most often associated with Marxism, but may also be associated with other perspectives such as critical theory, feminist theory, postmodern theory, queer theory, and race-conflict theory.

Conflict theories are perspectives in social science that emphasize the social, political, or material inequality of a social group, that critique the broad socio-political system, or that otherwise detract from structural functionalism and ideological conservatism. Sociologists in the tradition of conflict theory argue that the economic and political structures of a society create social divisions, classes, hierarchies, antagonisms and conflicts that produce and reproduce inequalities. Certain conflict theories set out to highlight the ideological aspects inherent in traditional thought. While many of these perspectives hold parallels, conflict theory does not refer to a unified school of thought, and should not be confused with, for instance, peace and conflict studies.

Of the classical founders of social science, conflict theory is most commonly associated with Karl Marx (1818–1883) . Based on a dialectical materialist account of history, Marxism posited that capitalism, like previous socioeconomic systems, would inevitably produce internal tensions leading to its own destruction. Marx ushered in radical change, advocating proletarian revolution and freedom from the ruling classes. At the same time, Karl Marx was aware that most of the people living in capitalist societies did not see how the system shaped the entire operation of society. Just like how we see private property, or the right to pass that property onto our children as natural, many of members in capitalistic societies see the rich as having earned their wealth through hard work and education, while seeing the poor as lacking in skill and initiative. Marx rejected this type of thinking and termed it false consciousness, which involves explanations of social problems as the shortcomings of individuals rather than the flaws of society. Marx wanted to replace this kind of thinking with something Engels termed class consciousness, which is when workers recognize themselves as a class unified in opposition to capitalists and ultimately to the capitalist system itself. In general, Marx wanted the working class to rise up against the capitalists and overthrow the capitalist system.

Healthcare reform supporter

Karl Marx wanted to replace false consciousness with class consciousness, in which the working class would rise up against the capitalist system.

Two early conflict theorists were the Polish-Austrian sociologist and political theorist Ludwig Gumplowicz (1838–1909) and the American sociologist and paleontologist Lester F. Ward (1841–1913). Although Ward and Gumplowicz developed their theories independently, they had much in common and approached conflict from a comprehensive anthropological and evolutionary point-of-view as opposed to Marx’s rather exclusive focus on economic factors.

- Wright Mills has been called the founder of modern conflict theory. In Mills’s view, social structures are created through conflict between people with differing interests and resources. Individuals and resources, in turn, are influenced by these structures and by the “unequal distribution of power and resources in the society. ” Mills argued that the interests of the power elite of American society (for example, the military-industrial complex) were opposed to those of the people. He theorized that the policies of the power elite would result in the “increased escalation of conflict, production of weapons of mass destruction, and possibly the annihilation of the human race. “

Conflict theory is most commonly associated with Marxism, but as a reaction to functionalism and the positivist method, it may also be associated with a number of other perspectives, including critical theory, feminist theory, postmodern theory, post-structural theory, postcolonial theory, queer theory, world systems theory, and race-conflict theory.

The Labeling Approach

Key Points

- Developed by sociologists during the 1960s, labeling theory holds that deviance is not inherent to an act. The theory focuses on the tendency of majorities to negatively label minorities or those seen as deviant from standard cultural norms.

- The social construction of deviant behavior plays an important role in the labeling process that occurs in society.

- Labeling theory was first applied to the term “mentally ill” in 1966 when Thomas J. Scheff published Being Mentally Ill. Scheff challenged common perceptions of mental illness by claiming that mental illness is manifested solely as a result of societal influence.

- Hard labeling refers to those who argue that mental illness does not exist. They note the slight deviance from the norms of society that cause people to believe in mental illness.

- Soft labeling refers to people who believe that mental illnesses do, in fact, exist. Unlike the supporters of hard labeling, soft labeling supporters believe that mental illnesses are not entirely socially constructed.

Labeling Theory on Health and Illness

Labeling theory is closely related to social-construction and symbolic-interaction analysis. Developed by sociologists during the 1960s, labeling theory holds that deviance is not inherent to an act. The theory focuses on the tendency of majorities to negatively label minorities or those seen as deviant from standard cultural norms. The theory is concerned with how the self-identity and behavior of individuals may be determined or influenced by the terms used to describe or classify them. It is associated with the concepts of self-fulfilling prophecy and stereotyping .

The social construction of deviant behavior plays an important role in the labeling process that occurs in society. This process involves not only the labeling of criminally deviant behavior—behavior that does not fit socially constructed norms—but also labeling that reflects stereotyped or stigmatized behavior of the “mentally ill.” Hard labeling refers to those who argue that mental illness does not exist; it is merely deviance from the norms of society that cause people to believe in mental illness. Mental illnesses are socially constructed illnesses and psychotic disorders do not exist. Soft labeling refers to people who believe that mental illnesses do, in fact, exist, and are not entirely socially constructed.

Labeling theory was first applied to the term “mentally ill” in 1966 when Thomas J. Scheff published Being Mentally Ill. Scheff challenged common perceptions of mental illness by claiming that mental illness is manifested solely as a result of societal influence. He argued that society views certain actions as deviant. In order to come to terms with and understand these actions, society often places the label of mental illness on those who exhibit them. Certain expectations are placed on these individuals and, over time, they unconsciously change their behavior to fulfill them. Criteria for different mental illnesses, he believed, are not consistently fulfilled by those who are diagnosed with them because all of these people suffer from the same disorder. Criteria are simply fulfilled because the “mentally ill” believe they are supposed to act a certain way—over time, they come to do so.

Another issue involving labeling was the rise of HIV/AIDS cases among gay men in the 1980s. HIV/AIDS was labeled a disease of the homosexual and further pushed people into believing homosexuality was deviant. Even today, some people believe contracting HIV/AIDS is punishment for deviant and inappropriate sexual behaviors.

Labels, while they can be stigmatizing, can also lead those who bear them down the road to proper treatment and recovery. The label of “mentally ill” may help a person seek help, such as psychotherapy or medication. If one believes that being “mentally ill” is more than just believing one should fulfill a set of diagnostic criteria, then one would probably also agree that there are some who are labeled “mentally ill” who need help. It has been claimed that this could not happen if society did not have a way to categorize them, although there are actually plenty of approaches to these phenomena that don’t use categorical classifications and diagnostic terms (for example, spectrum or continuum models). Here, people vary along different dimensions, and everyone falls at different points on each dimension.

Social Epidemiology and Health

Key Points

- Epidemiology is the study (or the science of the study) of the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations.