November is Native American History Month, and a good time for New Yorkers to acknowledge and honor the indigenous peoples who lived here before us. The Lenape thrived for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. They called their homeland Lenapehoking, and their territory included portions of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

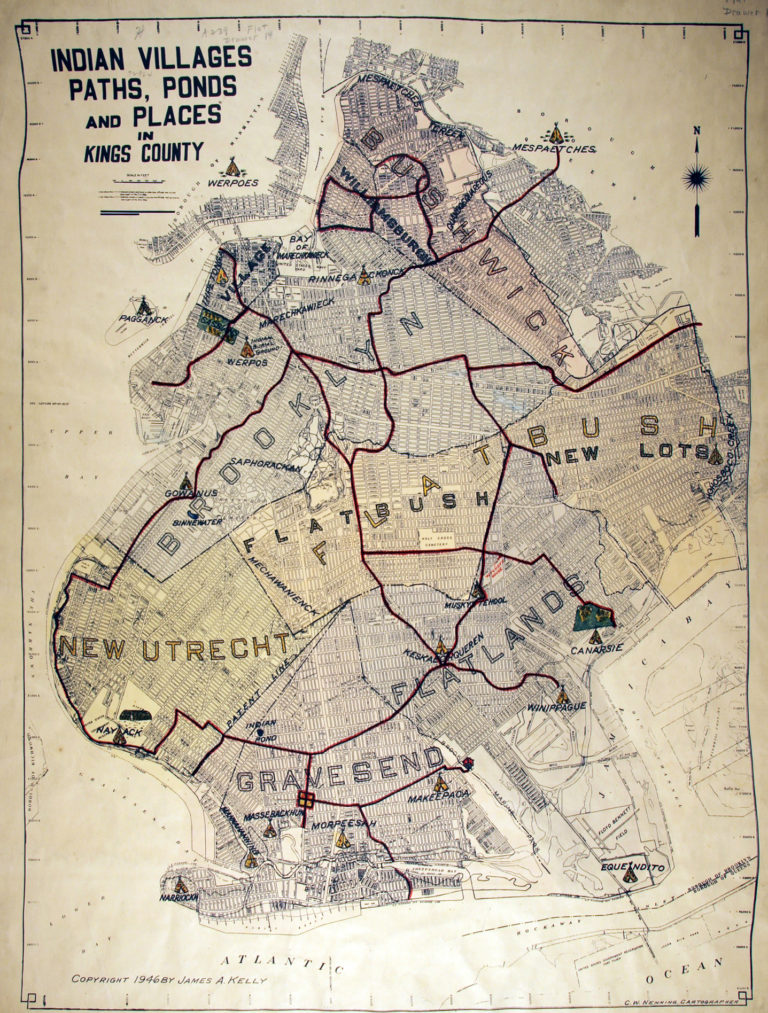

In Brooklyn, the Lenape had settlements in what are now the neighborhoods of Bushwick, Canarsie, Flatlands, Fort Hamilton, Gowanus, and Sheepshead Bay.

The concept of shared land use was fundamental to Lenape society. Lenape peoples lived in fixed settlements, and their lives revolved around communal hunting and planting. Planting was managed by women, who cultivated corn, squash, beans, and tobacco. The men cleared the field and broke the soil. During the rest of the year, they would fish and hunt.

The arrival of Europeans was devastating to the Lenape. By the 17th century, Europeans were setting up colonies to extract resources from Lenapehoking. They pushed the Lenape out of the East Coast and pressed them to move west. In 1626, the Lenape “sold” the island of Manahatta to the Dutch. The Dutch were of course deceptive in their dealings, as the concept of private land-ownership was not recognized by the Lenape.

The loss of land led to a scarcity of essential resources, as the Lenape peoples could not farm and were forced to over-hunt. Their population fell sharply, due to infectious diseases brought by Europeans, such as measles and smallpox. Between 1600 and 1700, the Lenape were decimated by diseases and war. By 1750, they had lost an estimated 90% of their people.

The Treaty of Easton, signed in 1758 between the Lenape and the English, forced the Lenape to move westward into Pennsylvania and Ohio. Other deceptive land treaties and forced migrations followed, and the Lenape were pushed further and further west. In the 1860s, the federal government sent Lenape remaining in the eastern United States to the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) under the Indian removal policy. Today, Lenape communities are found in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Wisconsin, Ontario, and New Jersey.

Land acknowledgements, or statements serving as offerings of honor and respect, are one way to pay respect to the Lenape and other tribes who were killed and displaced by European settlers. Land acknowledgements are not a substitute for substantial reparative justice but they can raise awareness about histories that are often suppressed or forgotten.

The acknowledgement process involves asking: “Who lived here before us?” “What happened to them?” “Who should be accountable for their displacement?” “What can be done to repair the harm done to them?”

The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture (not a real government agency but a “people-powered department”) offers a resource called Honor Native Land: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement.

Here are their answers to the question: “Why practice Land Acknowledgement?”:

- Offer recognition and respect

- Share the true story of the people who were already here

- Create a broader public awareness of history

- Begin to repair relationships with Native communities

- Support larger truth-telling and reconciliation efforts

- Remind people that colonization is an ongoing process

- Opening up space with reverence and respect

- Inspire ongoing action and relationships

And here is their step-by-step guide to acknowledgment:

- Identify: “The first step is identifying the traditional inhabitants of the lands you’re on. . . it is important to proceed with care, doing good research before making statements of acknowledgement.”

- Articulate: “Once you’ve identified the group(s) who should be recognized, formulate the statement.. . . Beginning with just a simple sentence would be a meaningful intervention in most spaces.”

- Deliver. “Offer your acknowledgement as the first element of a welcome to the next public gathering or event that you host . . . Consider your own place in the story of colonization and of undoing its legacy.”

How can we do reparative work with Native communities who still live in New York? What role can an educational space like City Tech, on occupied Lenape land, play in reparative justice?