As anyone who has heard me speak about predatory publishing knows, there are non-predatory journals that fall into a grey area of quality. They abuse “overproduction” of articles by excessive promotion of special issues or pressure on editors to attract and accept more articles. In particular, newer open access publishers including Hindawi, MDPI, and Frontiers were called out for these practices. Hindawi, which Wiley purchased, ultimately was dissolved as a brand and four of its journals ceased publication. More pertinent to City Tech faculty, an article in the Wall Street Journal on March 13 discusses how several of the big five scholarly publishers, specifically Elsevier, Wiley, and Springer Nature, are in an “arms race” to publish more and more papers. Editors are very unhappy, of course.

Sage Research Methods

We’re very excited to announce a great new resource for faculty performing original research: Sage Research Methods.

Sage Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. It provides more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher.

International Journal of Transformative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (IJTTL)

Faculty whose scholarship focuses on teaching and learning may be interested to learn that the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Stony Brook University recently launched a new journal, International Journal of Transformative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

Faculty whose scholarship focuses on teaching and learning may be interested to learn that the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Stony Brook University recently launched a new journal, International Journal of Transformative Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.

This new journal is open access and does not require any author fees for publication.

What’s up with policies related to open access and open science?

It’s Open Access Week 2024, Oct. 21-27. This year’s theme, Community over Commercialization, continues a thread from last year’s theme, “It Matters How We Open Knowledge: Building Structural Equity.”

It’s Open Access Week 2024, Oct. 21-27. This year’s theme, Community over Commercialization, continues a thread from last year’s theme, “It Matters How We Open Knowledge: Building Structural Equity.”

I recently read this blog post by Professor Lorena A. Barba (George Washington University) that nicely sums up United States policy on open access and open science. Any faculty member receiving federal funding should take the time to read this post about big changes in the making and librarians should also be familiar with how funder requirements impact researcher practices .

Publishing Success Tidbits: The Article Submission Cover Letter Email

Authors may need to send a cover letter when submitting an article to a journal. There is an art to preparing an article submission cover letter. Reimagining the Covering Letter: Why, When, and How to Communicate with Journal Editors before Manuscript Submission by Steven Gump in the Journal of Scholarly Publishing is a helpful guide. Log in with your CUNY email/password to access the article.

Why Is My Book So Expensive? The Cost of a Scholarly Monograph

Why Is My Book So Expensive? The Cost of a Scholarly Monograph

Catherine Cocks

a repost from A Five Year First Friday Feature from Feeding the Elephant: A Forum for Scholarly Communications.

Post by Catherine Cocks, director, Syracuse University Press.

Authors often ask publishers, “Why is my book so expensive?” The short answer: it really isn’t that expensive. The long answer: your scholarly book might cost more than commercially published nonacademic books because academic presses are spreading the cost of producing a title across a smaller number of print units. Each unit therefore has to be priced higher to enable the press to recoup the cost of production.

The longer answer: In the past, say the halcyon 1980s, academic presses could count on selling about 1,500 copies of the average scholarly monograph. Most of the buyers were college and university libraries. An initial, small cloth edition priced relatively high and aimed primarily at those libraries would ideally earn enough revenue to offset a significant proportion of the production costs. If it did and the cloth copies sold out, then the press would print a paperback edition that could be priced in the $20 to $30 range. Or, the publisher might issue the cloth and paper editions simultaneously, trying to cover its costs by catering to both library and individual buyers.

Then the digital revolution happened. Libraries needed to invest heavily in hardware and software to make the new electronic resources available to their campuses. At the same time, library budgets were flat or falling (largely because of the widespread reduction in public funding for higher education, which is the essential context for this whole post). The money for these new and rapidly changing resources had to come from somewhere, and it generally came from the budget for monographs in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. STEM journal subscriptions in particular became increasingly expensive and took up a growing proportion of library budgets. In short, libraries bought more databases and journals and fewer books.

This change in library priorities meant that the market for scholarly monographs shrank, and it continues to shrink. Academic presses responded by printing fewer copies of each title, to avoid piling up unsold copies for which they might have to pay warehousing and eventually pulping fees. Meanwhile, although the digital revolution transformed publishers’ production processes, it didn’t significantly reduce costs. Nor did the advent of the e-book in the early 2000s. Printing accounts for only about a third of total book production costs on average, while electronic scholarly monographs are generally sold via databases provided by aggregators. Presses earn pennies on the dollar on such sales, compared with sales of individual print copies. Libraries’ turn to patron-driven acquisitions (essentially, waiting until someone clicks on a title to purchase it) further reduces publishers’ revenue and makes it less predictable.

Although short-run digital printing and print-on-demand have made it more affordable to print fewer copies without sacrificing too much in quality, these new options reduce up-front costs without necessarily making the overall publishing program sustainable.

So prices are going up (and have been going up for decades) because publishers now can expect to sell fewer⏤sometimes many fewer⏤than 500 copies in all formats of the average scholarly monograph. They have to spread similar costs over a third of the units. Although short-run digital printing and print-on-demand have made it more affordable to print fewer copies without sacrificing too much in quality, these new options reduce up-front costs without necessarily making the overall publishing program sustainable. Prices have to rise if presses are to have any hope of recouping their costs. Though university presses are nonprofits, just recovering production costs doesn’t cover all of their expenses, nor does it give them the leeway to innovate⏤for example, by taking advantage of new digital technologies or building new platforms for multimedia scholarship.

What are those production costs? Direct costs are those paid specifically to create a title. Typically they include copy editing, design of the cover and the interior of the book, typesetting, e-book conversion if needed, printing, binding, and shipping. (Proofreading and indexing are by necessity now mostly left to authors.) The longer the book, the more illustrations that have to be cleaned up and placed in the typeset pages, the more complex the apparatus, the more it will cost to edit, design, typeset, print, and ship. Color inks cost more, and color pages usually have to be run on higher quality, more expensive paper on separate machines, then reintegrated with pages run in grayscale. A book produced entirely in color is even more expensive. All of these elements contribute to the cost, and therefore the price, of the book.

Indirect costs are a proportion of the press’s overhead assigned to a book project. Overhead includes salaries and benefits for the acquisitions editor who worked with the author from proposal through peer review and editorial board approval, the project editor who shepherded the book through production, and the marketer who got the word out in various ways from entering metadata to sending email blasts and arranging book signings. Like many American workers, people in publishing have seen their salaries remain the same or barely creep up even as the cost of living has increased substantially, particularly in big cities and many college towns. Overhead also includes the press’s rent, royalty administration, title management database fees, and much more of the unglamorous and essential back-end processes. (For more on this topic, see “The Costs of Publishing Monographs: Toward a Transparent Methodology.”)

Presses use a variety of pricing strategies to try to ensure that each title breaks even or at least that the overall publishing program is sustainable. Some continue to use the time-tested strategies mentioned above⏤cloth, then paper or simultaneous cloth and paper editions at different prices. Others have dispensed with the cloth edition (whose price may discourage sales) and go straight to paper, but at a higher price to offset the absence of cloth sales. Those very high prices you see from some publishers⏤say $80 to $120 for a slim monograph⏤reflect both very short print runs (perhaps 100 to 250 units) and the fact that libraries, which are less price-sensitive than individuals, are the only customers likely to buy significant numbers. (Yes, publishers have tried lowering prices in the hope of attracting more buyers. It doesn’t usually pencil out.) Presses often use a variety of approaches to account for different purchasing patterns by individuals and libraries across disciplines. Another strategy is to keep book prices artificially low, losing money on them while balancing the press’s books with a profitable journal program or distribution services.

The other thing to understand about pricing is that publishers rarely earn the full list price of a book because they don’t sell most of their titles directly to consumers. Far more often, they are selling to wholesalers and retailers who then sell to libraries and individuals. Wholesalers and retailers buy at a discount (typically 20% to 50% or more) off list price so that they can recoup their own costs and hopefully earn a profit selling the books to the end user. When publishers set list prices, they are taking into account the fact that the actual sale price will most often be significantly lower. On top of that, publishing is highly unusual in that wholesalers and retailers can return unsold stock any time⏤sometimes years after the initial sale.

This is a simplified sketch of what goes into determining a scholarly monograph’s cost and therefore its price. I hope it underscores the point that right now, scholarly book publishing faces many challenges in fulfilling its mission to circulate the fruits of academic research. Many people are trying to rethink its business model to be more sustainable for the long run. In the Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem and Knowledge Unlatched initiatives, universities or university libraries collectively invest in presses up front, and presses then make the books available to readers for free. The US National Endowment for the Humanities has also offered publication grants aimed at fostering open access scholarly publishing through the Open Book and the Fellowship Open Book programs. Taking a different approach, the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot consolidates production work and produces an e-first edition with a print-on-demand option to member presses. Individual presses have also adapted the author-pays model from journals to book publishing, and some universities are providing such funding to their tenure-track faculty. The Elephant’s interview with the University of Michigan Press’s Charles Watkinson on open access explores some of the possibilities and hurdles involved in transforming the business model. Have something to add? We’d love to hear from you.

Catherine Cocks is the director of Syracuse University Press. She has worked in scholarly publishing since 2002 beginning as a managing editor at SAR Press, an acquisitions editor at the University of Iowa Press and the University of Washington Press, then editor-in-chief and interim director at Michigan State University Press. As a member of AUPresses committees, she is a proud contributor to the Best Practices in Peer Review and the Ask UP website. As a member of the Publishing and the Public Humanities Working Group, she helped to write “Public Humanities and Publication” and co-authored the Open Educational Resource “Publishing Values-Based Scholarly Communications” with Bonnie Russell and Kath Burton. In her former side-gig as a historian, she wrote two scholarly books, Doing the Town: The Rise of Urban Tourism in the United States, 1850-1915 (University of California Press, 2001), and Tropical Whites: The Rise of the Tourist South in the Americas (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

Publishing success tidbits: Desk rejections

When editors reject articles (deciding not to send the article to peer reviewers), this is called a desk rejection. Often, articles are rejected because they are out of scope. That means article content doesn’t align with the journal’s purview (scope). “Your Manuscript Was Not Sent Out for Review” explains desk rejections from the perspective of an editor. If free access via the link above doesn’t work, please access the article via CINAHL, logging in from off-campus.

Demystifying that Paragraph about Copyright in Your Book Contract

Read your contract! Not so easily done, especially for authors of books. Book contracts are long, dense, and confusing. The essay below is a guest post by Stephanie Vyce, director of intellectual property, Harvard University Press, for H-Net’s excellent Feeding the Elephant: A Forum for Scholarly Communications.

The legal agreement you have with your publisher does many things. Two of the most important are articulating how the publisher may publish and use your work and how copyright registration and enforcement will be handled.

When you enter into an agreement with a publisher, you are deliberately ceding at least some of your publishing rights to the publisher in exchange for their services and any compensation they may offer. Your publisher may propose handling any and all publishing rights, in which case you may opt to take advantage of their expertise in selling and licensing your work in all formats by assigning all rights to them. Or, you may wish, at the start, to control certain rights yourself. The terms of your publishing agreement should define the rights your publisher will handle. This part of the contract will have an impact on how copyright can be registered and enforced.

Copyright is, simply, the right to make and make use of copies. (See the US Copyright Office’s Circular 1 Copyright Basics for more information.) Except in some special cases, when you create an original work, you are, automatically, the copyright holder and have the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform it, with some limited exceptions (such as fair use and parody, both of which can be exploited by others without your permission).

Though copyright registration is not required to possess copyright, it is an important step in protecting your work as registration is a prerequisite for filing suit and registration creates a verifiable record of a given work so that the copyright owner can more easily demonstrate their ownership in the event of a legal claim.

The terms of your agreement will spell out who is responsible for enforcing copyright. If registered in your name, you may be assuming responsibility for enforcing the copyright in your work. If registered in the name of your publisher, or, in the case of some university presses, in the name of their institution, they will typically assume that responsibility. Having the copyright in the name of your publisher may provide you with a valuable benefit, as they often have the tools and expertise to respond to copyright infringement that you as an individual might not possess or have easy access to.

Check your contract for two important concepts: assignment and license. Should you choose to assign all rights to your publisher, copyright cannot be registered in your name because you are, in that case and by definition, ceding all of your rights. If you grant a license to all or certain rights to your work, you are allowing your publisher to make use of those rights but still own the rights yourself. In this case, copyright can be registered in your name, because the rights belong to you. If having copyright registered in your name at publication is important to you, you will need to be clear about your intention to assign or grant a license, and in the case of granting a license, negotiate with your publisher which right or rights you will retain and handle yourself or through another party, like an agent. Note that registering copyright in your own name does not automatically mean you can exercise all rights. You’re still licensing some or all of them to your publisher to exercise on your behalf.

If copyright is registered in the name of your publisher and your agreement is ever canceled, you can request a transfer of copyright to you as part of the reversion of rights, the terms of which should be included in your agreement. Your contract might include a clause setting out how rights reversion will work in the event that the contract is terminated.

The assignment or licensing of rights and the registration of copyright are two complementary but distinct negotiating points in any publishing agreement. Having clear language about which party—you or your publisher—will handle certain categories of publishing rights and in whose name copyright will be registered, and by extension which party is responsible for enforcing that copyright, will set both you and your publisher up for success. Be sure to consult with the Office of the General Counsel of your institution, your agent, our your own lawyer for advice on making the best decision for you.

Stephanie Vyce started her career in books at the Harvard Bookstore in Harvard Square where she was a bookseller for two years. She then joined the sales department at Harvard University Press and represented Harvard, Yale, and MIT Presses to accounts from Vermont to Virginia. Next stop, Subsidiary Rights Manager, responsible for licensing translation, reprint, dramatic, and audio book rights to HUP titles. Since 2012, she has been the Director of Intellectual Property at HUP.

https://networks.h-net.org/group/discussions/20023278/demystifying-paragraph-about-copyright-your-book-contract.

published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License

Diamonds for authors #1: Subscribe to Open

This post, the first in a series, introduces City Tech faculty to free-to-author, immediate open access publishing options.

This post, the first in a series, introduces City Tech faculty to free-to-author, immediate open access publishing options.

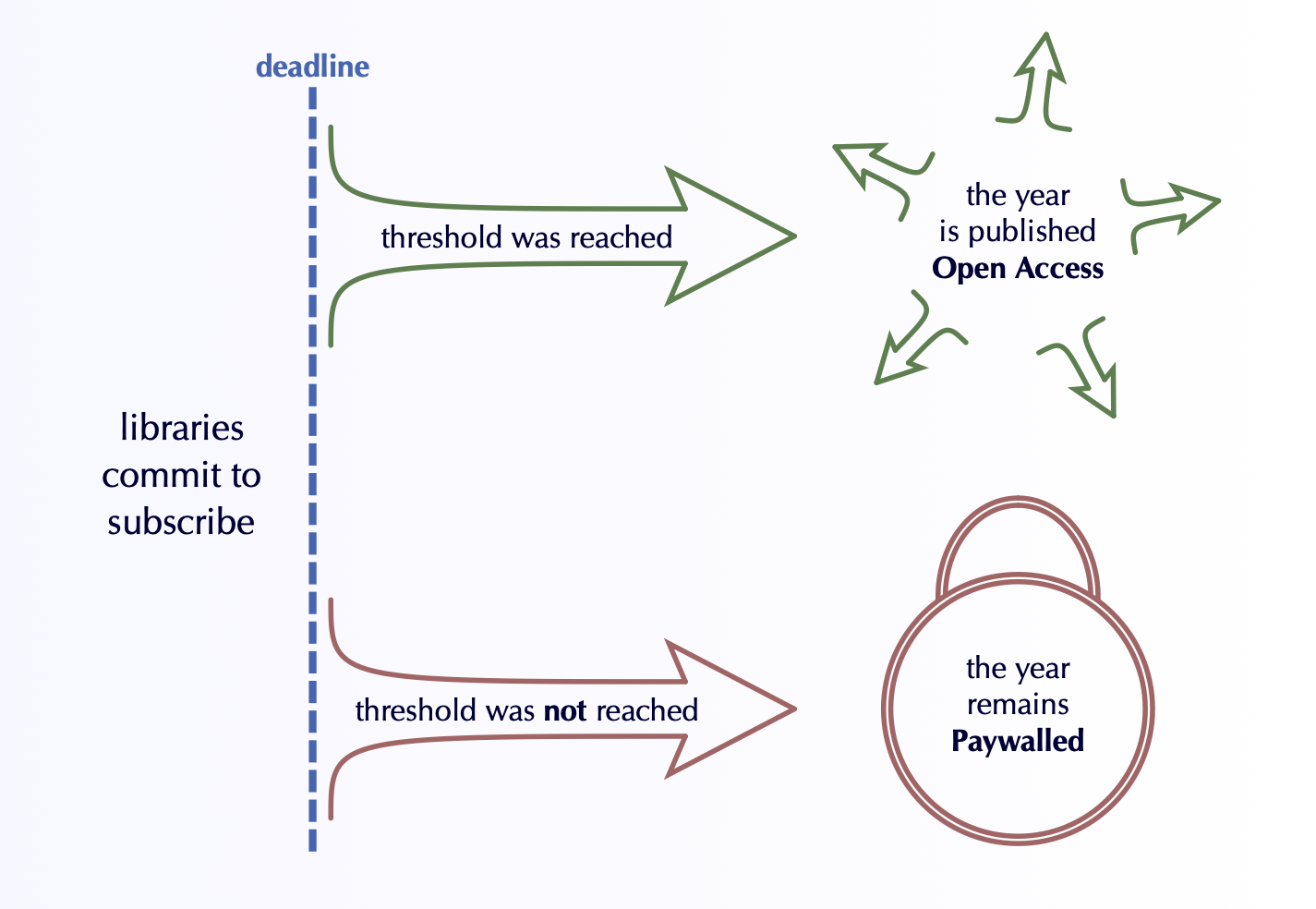

Not all open access is funded the same way and the scholarly publishing community has proven highly creative in designing new models and related initiatives that grow diamond open access, open access without fees to authors. One of the larger programs is Subscribe to Open (S2O). Libraries pay part of their journal subscription funds to support ‘flipping’ a subscription journal to diamond open access. S2O, with funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, was created by non-profit science publisher Annual Reviews. As of the end of 2023, 151 journals are using the S2O model.

Not all open access is funded the same way and the scholarly publishing community has proven highly creative in designing new models and related initiatives that grow diamond open access, open access without fees to authors. One of the larger programs is Subscribe to Open (S2O). Libraries pay part of their journal subscription funds to support ‘flipping’ a subscription journal to diamond open access. S2O, with funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, was created by non-profit science publisher Annual Reviews. As of the end of 2023, 151 journals are using the S2O model.

S20 doesn’t convert all journals from a specific publisher to diamond open access but rather clusters of titles deemed important enough to merit the funding to convert. Publisher and library participants in S2O represent a wide variety of disciplines and geographical locations. You can peruse the list of the specific journals that have been flipped under S20. Interested in finding other diamond open access journals? It’s easy to use the Directory of Open Access journal search tool and filter by ‘without fees.’

Mathematical Sciences Publishers recently announced that, via S2O, five of their most popular journals are now diamond open access: Geometry & Topology, Algebraic & Geometric Topology, Algebra & Number Theory, Analysis and PDE, Pacific Journal of Mathematics.

Diamond by Nadia Zilfah from Noun Project (CC BY 3.0)

Working with Your Editor: Previously Published Material in Your Manuscript

Book authors sometimes incorporate text from their dissertations or previous publications in their book manuscripts. How to handle reuse, with or without modification, is confusing and touches on copyright and authors rights: authors should always review their contract and may need to request permission to reuse their writing. The essay below is a Guest post by Walter Biggins, editor-in-chief, University of Pennsylvania Press, for H-Net’s excellent Feeding the Elephant: A Forum for Scholarly Communications.

In short: Your manuscript probably has a lot of bunches, folds, and lumps. That’s not bad, so long as the presentation is as smooth as possible, in ways that are clean and clear to you and to your press alike.

One of the most common lumps, and sometimes the most time-consuming and process-disorienting to sort out, involves previously published material. Authors often think about material that comes from outside their own work as the problematic wrinkles—i.e., permissions. Do you have permission to reproduce that Warhol painting in your book? Or that map of Mordor? Or those Notorious B.I.G. lyrics? Or that seven-page extract from The Magic Mountain? Can you use this Bob Dylan verse as an epigraph to chapter 3, because you like it and, golly, that seems like fair use to you?

All that is worth considering, and needs to be resolved before you submit a final manuscript. (Spoiler alert: get rid of the Dylan.) But, in concentrating so acutely on the problems that might be caused by others’ work, you often forget to think of your own. In this manuscript, you should ask yourself, what of my own work has appeared elsewhere, and what should I do about that material?

Usually, your own previously published material could fall into five rough categories: scholarly articles published in peer-reviewed journals; essays published in an edited collection; pieces produced for mainstream media, such as magazines, newspapers, and other periodicals; material produced for non-print formats, such as podcasts and audiobooks; and conference papers.

In all of those cases except for the last one, you probably signed an agreement with the publisher of said periodical, book, or platform that granted the press the right to use your work. So, if a version of that material is going to be used in your book, you need to request permission for this—even if the original piece has been altered significantly for publication in book form.

For scholarly monographs and edited collections, there is typically no fee for this use, though the original periodical may request that your book attributes the source of the material properly. Ask if there is a specific credit line to be used, and a specific placement—on the copyright page, for example—where the credit should appear. Many contributor agreements for journals and inclusion in edited collections will include a clause granting permission of this sort; it’s worth requesting said clause if you don’t see it in the original agreement. Furthermore, many journals will spell out the specific granted rights for contributors on their websites, so check there as well.

It’s a good idea to check with a journal before you sign a contract with it about its terms for re-use of your material, and make sure that this is possible. It’s always worth finding out whether the contract stipulates if your work can be reproduced by the journal—in, let’s say, a best-of anthology of the journal—or if the journal can sell the right to have your material reproduced elsewhere, in other languages, and in other formats.

This can become a critical issue if your manuscript’s research was funded and/or sponsored in part by a university, academic affiliation, or institutional grant. An example: Let’s say your manuscript is a revised, greatly overhauled version of your dissertation. The university deposits the defended dissertation into its institutional repository. In doing so, it is possible that the work has been embargoed, which is to say access to it has been restricted in some way, usually for a limited period of time. The University of Oklahoma’s Libraries has a pretty good rundown on the reasons behind embargoes, and why you might choose this process for early versions of your work.

The main issue is that you need to be aware of what this means, and that embargoing parts of the work may mean that it’s problematic for it to appear in your book. You should make your book editor aware of any previously published material within your manuscript, and of the potential restrictions that this may cause, well before you submit everything.

…there’s a tricky balance between creating eager anticipation for the book and over-exposing it…

This is a practical consideration with legal ramifications. Your editor also needs to know how much, and where, your book’s material has appeared for marketing reasons. Your press certainly wants knowledge of your work, and acclaim for it, to be visible prior to the book’s publication. So, access to material related to the book is often a good thing. But there’s a tricky balance between creating eager anticipation for the book and over-exposing it so that its potential buyers think they already know the book—and thus don’t need to buy it. A good editor will be candid with you about how much of the work can be previously published before the exposure adversely affects its reception. My rule of thumb is no more than 25% of it should be accessible freely elsewhere; other editors will have different opinions. The point is: You should check, and plan accordingly.

That, in fact, is the key. At every step of the process, think carefully about what you’re published from the book, in what venues, and if you’ve got permission to do so. Ironing out this wrinkle will save you a lot of time and potential publication delay, and allow your experience to go as smoothly as it can.

Walter Biggins is Editor in Chief at University of Pennsylvania Press where he acquires cultural studies, intellectual and political history of the Americas, as well as Atlantic World and postcolonial studies. Biggins is also a freelance writer and is a coauthor of Bob Mould’s Workbook (Bloomsbury, 2017).

Biggins, Walter. “Working with Your Editor: Previously Published Material in Your Manuscript.” Feeding the Elephant: A Forum for Scholarly Communications., 2 Feb. 2024, https://networks.h-net.org/group/discussions/20022637/working-your-editor-previously-published-material-your-manuscript published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License ![]()