Effective reading requires more engagement than just reading the words on the page. In order to learn and retain what you read, it is a good idea to do things like circling key words, writing notes, and reflecting. Actively reading academic texts can be challenging for students who are used to reading for entertainment alone, but practicing the following steps will get you up to speed:

- Preview: You can gain insight from an academic text before you even begin the reading assignment. For example, if you are assigned a nonfiction book, read the title, the back of the book, and table of contents. Scanning this information can give you an initial idea of what you will be reading and some useful context for thinking about it. You can also start to make connections between the new reading and knowledge you already have, which is another strategy for retaining information.

- Read: While you read an academic text, you should have a pen or pencil in hand. Circle or highlight key concepts. Write questions or comments in the margins or in a notebook. This will help you remember what you are reading and also build a personal connection with the subject matter.

- Summarize: After you read an academic text, it is worth taking the time to write a short summary— even if your instructor does not require it. The exercise of jotting down a few sentences or a short paragraph capturing the main ideas of the reading is enormously beneficial: it not only helps you understand and absorb what you read but gives you ready study and review materials for exams and other writing assignments.

- Review: It always helps to revisit what you have read for a quick refresher. It may not be practical to thoroughly reread assignments from start to finish, but before class discussions or tests, it’s a good idea to skim through them to identify the main points, reread any notes at the ends of chapters, and review any summaries you’ve written.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Contents

Pre-reading

General Pre-reading Strategies:

- Check your environment and remove distractions.

- Activate your schema

- Survey the text (preview). Look at the headings and subheadings, any special features, and the length.

- Preview the text using the appropriate method.

- Learn new vocabulary.

Preview Method 1 (Use This When You Have A Title)

- Read the title. Use it to activate your schema.

- Ask, “What do I already know about this topic?” Jot down a quick list of what you know.

Sample Practice: The title of the book you will read is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

Ask yourself, “What do I already know about the life of Frederick Douglass?” Then make a list of your schema (prior knowledge) of Frederick Douglass.

Preview Method 2 (Use this for an article or chapter)

- Read the first and last paragraph.

- Read the first sentence of each paragraph.

- Write down or talk with a partner about what you expect you will learn about in the reading.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC licensed content, original

Modified from Making Connections: Mindful Reading and Writing. Authored by: Julie Damerell. Provided by: Monroe Community College. Located at: http://www.monroecc.edu/. License: CC BY: Attribution

Before reading

Use this preview method for a reading that does not have labeled sections or subtitles

Follow all of the steps for Before Reading and During Reading with a selected passage. Before you begin, number each of the paragraphs in the essay.

- Read the first and last paragraphs.

- Then read only the first sentence of every paragraph between the first and last.

- After you have read that much, write down the topic of the essay. Use the box below for this.

ANSWER FOR #3

| Topic of the essay: |

- The first paragraph of an essay is called the introductory paragraph and has a structure that is unlike the structure of body paragraphs. Instead of a topic sentence, it has a thesis. Underline the thesis of the reading. According to the thesis, predict three kinds of information the author will include in the text.

ANSWER FOR #4

| 1.

2. 3. |

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Public domain content – Modified from Making Connections. Authored by: Julie Damerell. Provided by: Monroe Community College. Located at: http://www.monroecc.edu/. License: CC BY: Attribution License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Pre-reading Activities

Pre-reading introduces the background and provides the context of reading. It also develops students’ prior knowledge for reading, especially for challenging texts. Pre-reading activities can occur in many forms and serve different purposes. Students can complete these guided activities in class or at home.

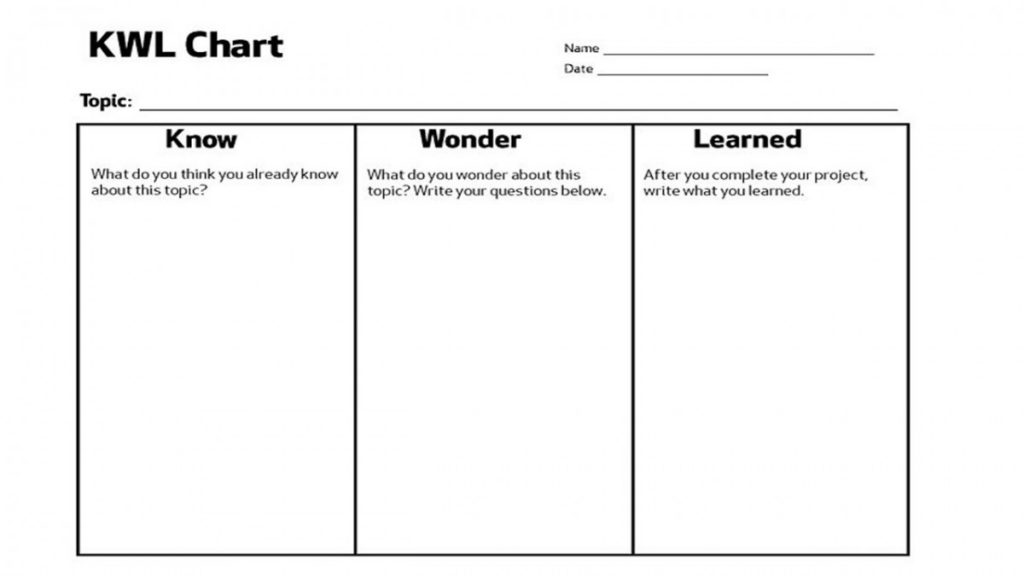

Pre-reading guides: these can include pre-reading questions that build students’ background knowledge about a topic. Anticipation guides ask students to match their perceptions to the actual knowledge presented in the texts. KWL charts connect students’ prior knowledge to what they are about to learn from reading.

Mind maps: they help students to associate their ideas and experiences to key concepts in the texts. They can be used in groups and class discussion as pre-reading activities.

Vocabulary previews: Introducing key or unfamiliar vocabulary words help prepare students for complex texts. A vocabulary guide/list can be used to ask students to apply Using Context Clues or Structural Analysis while reading or look up word meanings in advance.

Pre-reading Guides

These reading guides are designed to develop or activate a schema of background knowledge to facilitate critical reading and thinking through writing, visual mapping, and discussion. Some of the items/questions allow students to preview the reading, while others develop students’ vocabulary and awareness of certain concepts found in the texts.

| Pre-reading questions:

Before you read “Are College Lectures Fair?” by Annie Murphy Paul, briefly respond to the following questions: 1. Just by looking at the title, what do you think the author is going to discuss? 2. Can you think of instances when you felt that some lectures in high school or college took a specific cultural form that favored certain groups of people while discriminating against others? 3. Between lectures and active learning activities such as in-class learning exercises and projects, which do you prefer? Why? 4. Briefly describe the best classroom experience you have had in high school or college. |

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

“Pre-reading Activities” by Juanita But. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

“KWL Chart” from Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License

“Pre-reading Activities” by Juanita But. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Active Reading

One of the greatest challenges students face is adjusting to college reading expectations. Unlike high school, students in college are expected to read more “academic” type of materials in less time and usually recall the information as soon as the next class.

The problem is many students will spend hours reading and have no idea what they just read. Their eyes are moving across the page, but their mind is somewhere else. The end result is wasted time, energy, and frustration. . . and having to read the text again.

Although students are taught how to read at an early age, many are not taught how to actively engage with written text.

Active Reading is applying reading strategies before, during, and after reading a text with the overall objective of increasing comprehension (understanding what was read) and recall (remembering what was read) to save time and effort.

THE SECRET IS IN THE PEN

One of the ways proficient readers read is with a pen in hand. They know their purpose is to keep their attention on the material by:

- predicting what the material will be about

- questioning the material to further understanding

- determining what’s important

- identifying key vocabulary

- summarizing the material in their own words, and

- monitoring their comprehension (understanding) during and after engaging with the material

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC licensed content, shared previously. Active Reading. Authored by: Elisabeth Ellington and Ronda Dorsey Neugebauer . Provided by: Chadron State College. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution. ll rights reserved content. Learning how to Annotate. Authored by: Gale Shirey. Provided by: Southwestern Michigan College. Located at: http://youtu.be/zy45es1HyO0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Annotation

Annotation is often used to help students to identify important ideas, information, and vocabulary in the texts. Annotation can improve focus, retention, and summary of information and promote deep reading and understanding that enables higher order tasks such as analysis and evaluation of ideas in the texts; therefore, it should be taught explicitly in class. Though students can develop their own annotation style and uses symbols and marks based on their preferences, it is more effective for instructors to present models/guides for annotation and ask students to compare their own. In the process of annotating the texts, students can also engage in questioning and interacting with the text, making connection with other ideas, and setting up the stage for further research on specific topics.

Sample Annotation Practice

| College Reading Challenges and Practice Annotating One of the greatest challenges students face is adjusting to college reading expectations. Students in college are expected to read more academic type of materials in less time and usually recall the information as soon as the next class. The problem is many students spend hours reading and have no idea what they just read. Their eyes are moving across the page, but their minds are somewhere else. The end result is wasted time, energy, and frustration, and having to read the text again. Although students are taught how to read at an early age, many are not taught how to actively engage with written text or other media. Annotation is a tool to help you learn how to actively engage with a text or other media. Practice now: 1. Underline the part of the sentence above that gives you a definition of annotation. You should not underline the entire sentence. In the margin next to that line, write “D” or “Def” so remind you that what you marked is a definition. 2. Return to the first paragraph. In the first sentence, circle only the five words in the first sentence that name the challenge that many students face. In the second sentence, you get three characteristics of reading in college. Put a number over each one. In the margin, next to the paragraph, write “challenges.” 3. The second paragraph states a cause and an effect. What causes students to have to feel frustration about reading? IN YOUR OWN WORDS: 4 a) Write one sentence in which you state the challenge that many students face. 4b) Write another sentence in which you state the three characteristics of college reading. 4c) Write a third sentence in which you state a problem many students have related to college reading. 4d) In a fourth sentence write how annotation can help students deal with that problem. The Secret is in the Pen One of the ways proficient readers read is with a pen in hand. They know their purpose is to keep their attention on the material by: Predicting what the material will be about Questioning the material to further understanding. Determining what’s importantIdentifying key vocabulary Summarizing the material in their own words, and Monitoring their comprehension (understanding) during and after engaging with the material The same applies for actively viewing a film, video, image or other media. 5. What do good readers do with their pen while they are reading? In the second sentence, circle a good reader’s purpose for reading with a pen in hand. In the white space next to that sentence, the margin, write “purpose.” |

CC licensed content, original. Making Connections: Mindful Reading and Writing. Authored by: Julie Damerell. Provided by: Monroe Community College. Located at: http://www.monroecc.edu/. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, shared previously. Annotating. Authored by: Paul Powell. Provided by: Central Community College. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution

Annotating. Authored by: Elisabeth Ellington and Ronda Dorsey Neugebauer. Provided by: Chadron State College. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution

Active reading requires you to interact with what you read, and annotation is a tool to help you read actively. As the term “annotate,” suggests, you “take notes” in the text, so you should have a pen in your hand as you read. When you annotate, you can ask questions, make comments, and explain the meanings of words and concepts in the text. This process will help you retain information, concentrate better, have a deeper understanding of what the author says and the strategies the author uses to convey the information. It will also help you monitor and improve your comprehension, as well as find answers for the parts that you find confusing or difficult to understand.

The following is a list of some techniques for annotating a text:

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

“Annotation Guide” by Juanita But. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-Non Commercial

<

More about Annotation

While annotation appears to be a general activity to engage student reading, it takes on different forms and purposes. There are many creative ways to use annotations, which are especially useful in an integrated reading and writing classroom:

Students can also foster their skills in annotating texts by looking at best practices and useful guidelines and tips for effective annotation. A peer review guide can also help students improve their annotation techniques.

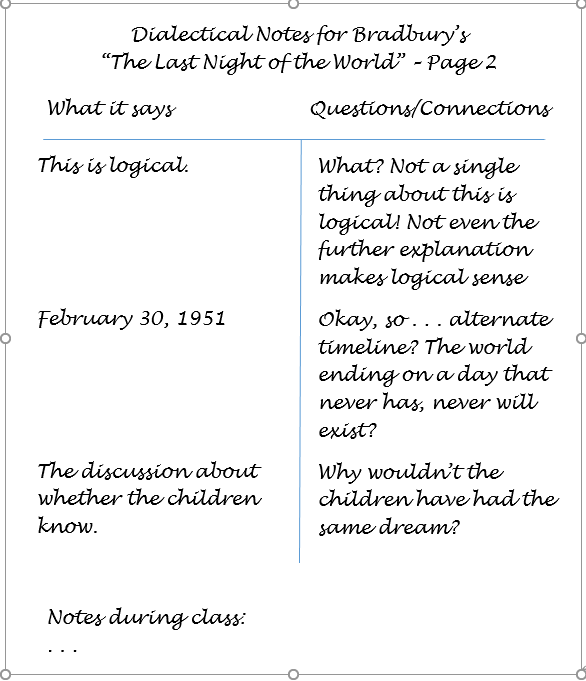

Dialectic Note-taking

A dialectical approach to taking notes sounds much more complicated than it is. A dialectic is just a dialogue, a discussion between two (or more) voices trying to figure something out. Whenever we read new material, particularly material that is challenging in some way, it can be helpful to take dialectic notes to create clear spaces for organizing these different sets of thoughts.

Creating Dialectic Notes

Start by drawing a vertical line down the middle of a fresh sheet of paper to make two long columns.

The Left Column

This column will be a straightforward representation of the main ideas in the text you are reading (or viewing). In it, you will note things like

- What are the author’s main points in this section?

- What kind of support is the author using in this section?

- Other points of significant interest?

- Note the source and page number, if any, so that you can find and document this source later

You candirectly quote these points, but do write them down as you encounter them, not after the fact. If you quote directly, use quotation marks; if you paraphrase, do not use quotation marks. Be consistent so that you don’t make more work for yourself when you start writing your draft. For more guidance with writing summaries, paraphrasing, and quoting, see the “Drafting” section of this text.

The Right Column

The right column will be the questions and connections you make as you encounter this author’s ideas. This might include

- Questions you want to ask in class

- Bigger-picture questions you might explore further in writing

- Connections to other texts you’ve read or viewed for this class

- Connections to your own personal experiences

- Connections to the world around you (issues in your community, stories on the news, or texts you’ve read or viewed outside of this class)

Bottom of the Page

It is often a good idea to leave space at the bottom of the page (or on the back) for additional notes about this piece you may want to write down based on what your instructor has to say about it or for comments and questions your peers make about it during class discussion.

Sample Dialectical Notes

Once you’ve finished the text and have taken your dialectic notes while reading it, you might have something that looks a bit like this (for the sake of the example, I read a story I’d never read before from an author I’m familiar with, so you could see genuine reactions to a first read):

Once you have this set of dialectic notes, there are a number of ways you can use them. Here are a few:

- They can help you contribute to class discussion about this piece and the topics it addresses.

- Significant questions you encountered while reading are already written down and collected in one place so you don’t have to sift back through the reading to re-discover those questions.

- These notes provide a place where many of your observations and thoughts about the piece are already organized, which can help you see patterns and connections within those observations. Finding these connections can be a strong starting point for written assignments.

- If you are asked to respond to this piece in writing, these notes can serve as a reference point as you develop a draft. They can give you new ideas if you get stuck and help keep the original connections you saw when reading fresh in your mind as you respond more formally to that reading.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Fix Up Strategies: What to do when you can’t understand the text

- Put a check next to the strategies you have already tried.

- Write a quick note in the margin about how those strategies did or didn’t work for you.

- Put a question mark next to 1-3 strategies that you have never tried.

- Put a star next to a strategy that you would like to try and/or that you would like explained.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Fix Up Strategies. Authored by: Enokson. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/edQPat. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Active Reading Practice

1. List what you already know about active reading.

2. Then read the paragraph below.

Successful students, and successful readers, approach reading with a strategy to help them get the most out of the reading. These students actively look for the main idea, the themes, for words they don’t understand, and the purpose (why the piece was written) of what they are reading. The opposite of active reading is passive reading. Passive readers only read because they are told to, skip over things they don’t understand, and have difficulty explaining what they have read. In this course, we are going to be practicing active reading. You will find that active reading is more enjoyable, lets you understand more of what you’ve read, and will lead to better test scores.

3. Return to the paragraph. Annotate four things the successful student looks for when she or he is reading.

4. Return to the paragraph. Use a different method to mark what a passive reader does.

5. Create a Venn diagram to show the differences between active and passive reading.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

- Making Connections: Mindful Reading and Writing. Authored by: Julie Damerell. Provided by: Monroe Community College. Located at: http://www.monroecc.edu/. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- ENG 9Y. Authored by: Jacqui Cain. Provided by: WA SBCTC. Located at: https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B0b0olJJwIXAMU9yeVF3ZVJ3QWc&usp=sharing&tid=0B9nrmpuRmC4ENDZiVDE3OVZrWGs#list. Project: Open Course Library. License: CC BY: Attribution

Post-reading

After reading the assigned texts, it is important for students to demonstrate understanding and see the relevance of their reading in terms of analyzing, evaluating, and applying the ideas in their writing. The best way to assess students’ understanding of the texts is to use post-reading activities. Post-reading can take various forms; they can be used as formal or informal assessments. Some examples of post-reading strategies are reading questions, critical responses, concept mapping, and student-generated questions and answers.

For post-reading activities to be relevant and effective, they have to allow students to apply critical reading skills that are required for comprehension and higher order thinking. Students can also reflect on the readings and examine the techniques and strategies the authors used to produce the texts.

Reading quizzes

Short questions on assigned readings can be designed to assess students’ competence in vocabulary, literal and inferential comprehension, analytical and critical reading. Quizzes can cover the CUNY Reading Outcomes:

CUNY Reading Outcomes

| Vocabulary development Determine the meaning of words and phrases as used in the text Comprehension Strategies Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences. Determine topics, central arguments, themes, main ideas and major and minor supporting points in academic texts. Paraphrase central points and or arguments, and key concepts Analytical Strategies Identify patterns of organization (including comparison/contrast, cause/effect, term definition. listing/classification, sequence/ chronology) to analyze relationships of ideas within texts. Distinguish between different types of written texts (e.g. informational, narrative, argumentative); recognize primary and secondary source distinctions. Understand disciplinary exam rhetoric. Interpret multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., quantitative data, maps, charts, multimedia) embedded in reading material. Critical Reading Identify author’s tone, style purpose, and point of view in texts from various content areas. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Analyze how multiple texts address similar themes or topics to evaluate or compare the authors’ points of view and approaches. |

Sample Reading Quiz

| Answer the following questions about Courtney Rubin’s “Technology and the College Generation.” Make sure that you read the text carefully while answering the questions. What is the main idea of this article? Based on the article, how do students and faculty perceive using emails in college? In the last paragraph, what exactly is the “surprising obstacle?” How does it relate to what the author has previously discussed in the article? In the article, what does Mr. Jones mean by saying “E-mail is a sinkhole where knowledge goes to die”? Do you agree with his statement? Why? |

LICENSE ATTRIBUTION

PART III: VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT

Both leaders and advertisers inspire people to take action by choosing their words carefully and using them precisely. A good vocabulary is essential for success in any role that involves communication, and just about every role in life requires good communication skills. We include this section on vocabulary in this chapter on reading because of the connections between vocabulary building and reading. Building your vocabulary will make your reading easier, and reading is the best way to build your vocabulary.

Learning new words can be fun and does not need to involve tedious rote memorization of word lists. The first step, as in any other aspect of the learning cycle, is to prepare yourself to learn. Consciously decide that you want to improve your vocabulary; decide you want to be a student of words. Work to become more aware of the words around you: the words you hear, the words you read, the words you say, and those you write.

Building a stronger vocabulary should start with a strong foundation of healthy word use. Just as you can bring your overuse of certain words to your conscious awareness in the previous activity, think about the kinds of words you should be using more frequently. Some of the words you might consciously practice are actually very simple ones you already know but significantly under-use or use imprecisely. For example, many students say he or she “goes” instead of he or she “says.” If you take it a step further, you can consider more accurate choices still. Perhaps, he “claims” or she “argues.” Maybe he “insists” or “assumes.” Or it could be that she “believes” or she “suggests.” This may seem like a small matter, but it’s important from both a reader’s and a writer’s perspective to distinguish among the different meanings. And you can develop greater awareness by bringing some of these words into your speech.

These habits are easier to put into action if you have more and better material to draw upon: a stronger vocabulary. The following tips will help you gain and correctly use more words.

• Be on the lookout for new words. Most will come to you as you read, but they may also appear in an instructor’s lecture, a class discussion, or a casual conversation with a friend. They may pop up in random places like billboards, menus, or even online ads!

• Write down the new words you encounter, along with the sentences in which they were used. Do this in your notes with new words from a class or reading assignment. If a new word does not come from a class, you can write it on just about anything, but make sure you write it. Many word lovers carry a small notepad or a stack of index cards specifically for this purpose.

• Infer the meaning of the word. The context in which the word is used may give you a good clue about its meaning. Do you recognize a common word root in the word? What do you think it means?

• Look up the word in a dictionary. Do this as soon as possible (but only after inferring the meaning). When you are reading, you should have a dictionary at hand for this purpose. In other situations, do this within a couple hours, definitely during the same day. How does the dictionary definition compare with what you inferred? 18 | Page

• Write the word in a sentence, ideally one that is relevant to you. If the word has more than one definition, write a sentence for each.

• Say the word out loud and then say the definition and the sentence you wrote.

• Use the word. Find occasion to use the word in speech or writing over the next two days. • Schedule a weekly review with yourself to go over your new words and their meanings. Or have a friend quiz you on the list of new words you have created.

College Success by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.