Discussing our case study project at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT

The Virtuvian triad still stands as a central conception of architecture, reinterpreted by the needs of modern society, linking shelter, purpose, and cultural meaning. Our communities need shelter from the changing forces of nature. We need spaces that serve their purpose but also our sense of purpose. We need meaningful places that enrich our lives and our spirit as the setting for the trials, celebrations and mundane activities of our lives.

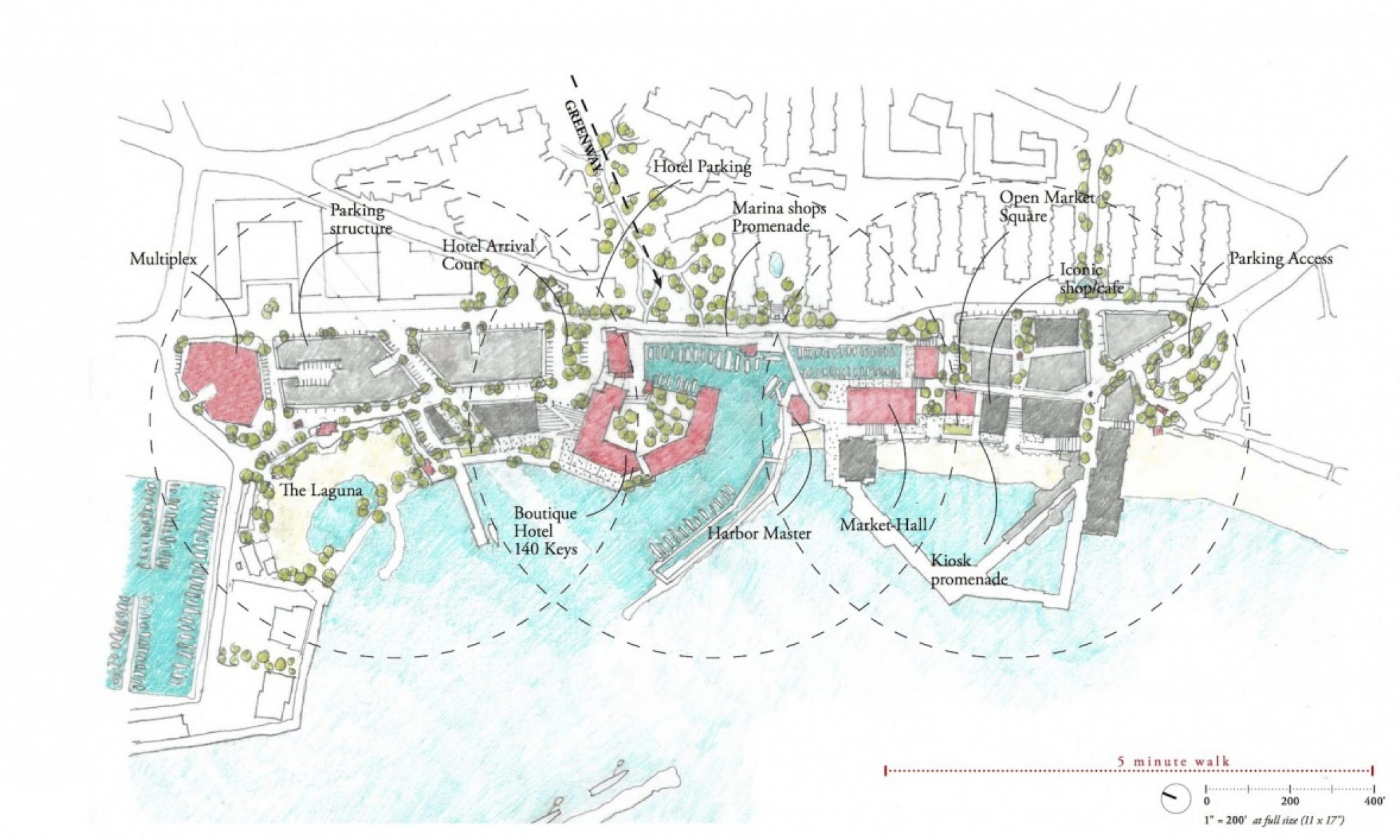

Architecture and urban design therefore serve the critical role of place-making, serving the heart, the mind, and the soul’s desire for beauty, for stimulation and understanding, for the transcendent. As such, teaching architecture and urban design translates as place-based learning. Students need to foreground place in their approach to the creative process.

Following from this premise, my teaching philosophy starts in the field, students with sketchbooks and cameras on hand, with observation and inquiry our tools for building knowledge. In the field the sensuous, poetic manifestation of space and form opens the door to the intellectual analysis of proportion, tectonic assembly, material manipulation. This analysis searches for system, parts, compositional rules, precedent, eccentric moments, response to environmental forces… This process is an active learning process, engaging and immersing the student, building a reservoir of knowledge, experience, and memory to draw upon in the creative process. Through observation and inquiry, the art and science of architecture can be appreciated by the student, supporting their balanced synthesis in new creative works.

Observation and inquiry as foundational modes of learning stand in contrast to a formal, formulaic basis of learning. In our moment in culture and history, architecture’s potential to be undermined by a consumerist fascination with superficial form threatens to rob us of meaningful places that nurture us. This is not to say there is no place for the study of formal language in architecture, but that it alone is unlikely to build the sensitivity and judgment for the making of meaningful places.

Observation and inquiry also offer an opportunity to make space for minority community’s whose voice is often absent from discussions of architecture. We can bring critical pedagogy into our classrooms, where students can be empowered to re-examine the conventional history and accepted stories of place through their lived experience, perspective, and interpretation, voicing new stories of place. Observation and inquiry empower diverse students to discover, interpret and build our collective depth of knowledge.

Observation and inquiry also help educators move past the passive teaching modes that we reflexively return to in our classrooms. With information ubiquitous, passive knowledge transfer has little value in comparison to the modes of teaching that have potential for deeper and higher levels of learning. I seek to make my classroom an active learning environment at all times, moving from discussion to demonstration to seminar to group activity, from one modality to another as appropriate to the learning goals.

The best outcome in education is the conversion of students to deep learners, with the ethos for life-long learning the gold standard. Our role as educators is to nurture this ethos with our passion, our intellectual perspective, and our faith that we can help build safe, purposeful, and meaningful places for community and common purpose.

As faculty our faith in architecture’s role in society goes further to ponder its contribution to building a just society. This is informed by our civic engagement, our intercultural knowledge, our dedication to teamwork, our ethical reasoning, our contribution in the search for environmental and social justice. Therefore we must infuse our teaching with these larger educational objectives.

All of these views of architectural education must be rooted in humility. Humility is a key driver of life-long learning. We must model humility and the desire to continue to grow and learn. Research is our mode of continuing our growth but also invigorating our teaching. Research connects us to history and to our current moment filled with immense challenges. Our students must be connected to these challenges, immersed in real world problems, and see the potential for their own research trajectory emerging through their education.

Presentations on Place-based Learning: