I am collaborating with my faculty colleagues to found a center at the college that will conduct multidisciplinary research and execute projects in neighborhoods of New York City and beyond in an effort to improve the livability of our urban environments.

To date we developed a mission statement and a prospectus and are proceeding with a review process with the college president’s office with a target launch of the center for spring 2020.

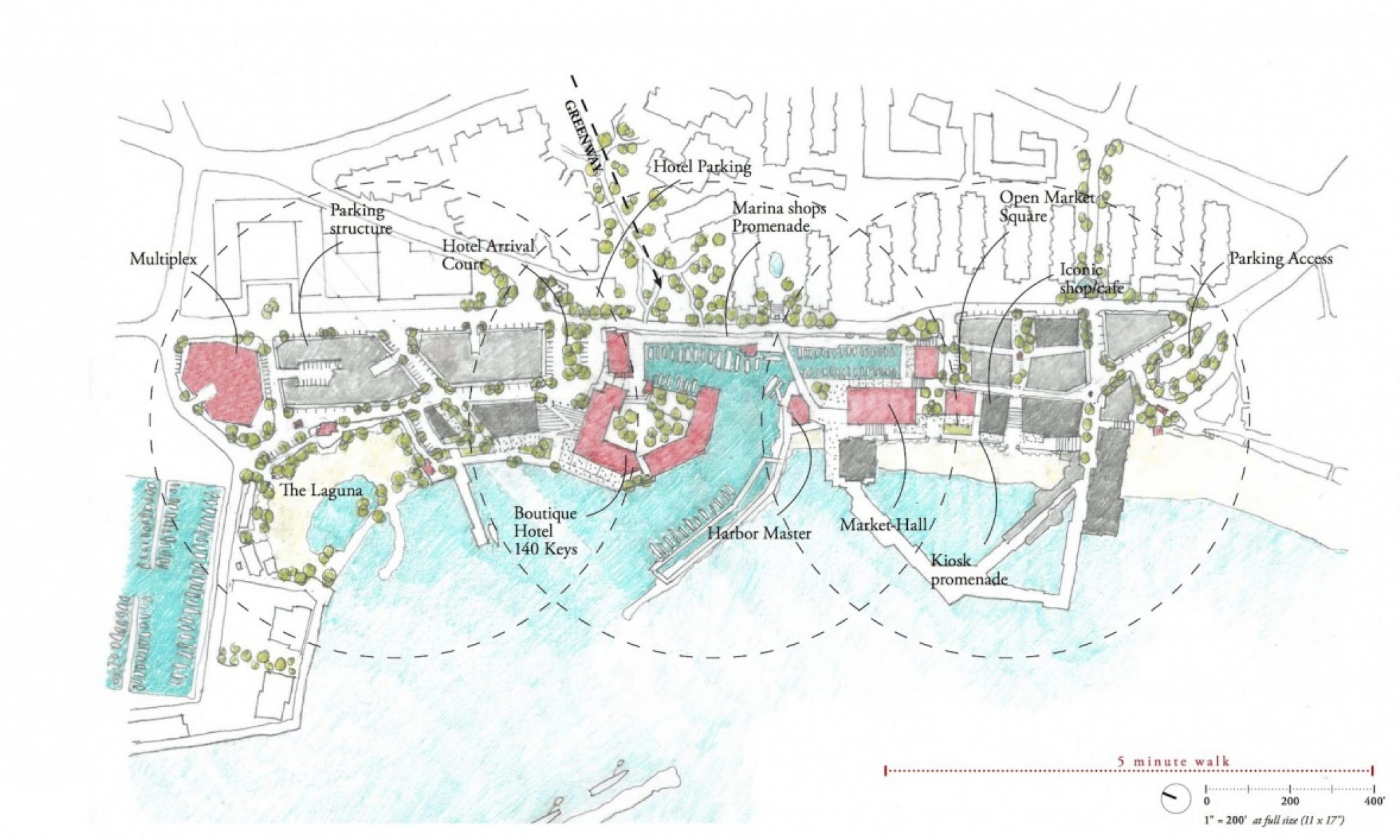

This center builds off the a number of projects and initiatives we led over the last 5 years centered on Downtown Brooklyn, including the two symposia Rethinking Jay Street and Ten Years Later: The 2004 Rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn,This center is also linked to our efforts teach in the Urban Design Studio, where our students analyzed downtown Brooklyn and define a number of strategic projects that would help knit the fabric and street network back together.

Studies of Downtown Brooklyn:

Evidence: RE: Center for Neighborhood Design Studies – Jason Montgomery

Jay Street and Downtown Brooklyn:

The world is urbanizing rapidly. Rural populations are losing the ability to sustain themselves economically, and seek opportunity in the mass of people, buildings, pavement of the city. The next chapter of the world will be an urban one. All of this in the context of a planet pushed to the extreme boundaries of sustainability.

Those of us that choose a career that focuses on researching and developing a strategy for the continued design of our cities have an urgent task: to accommodate the growing population, to foster/encourage economic, social, racial diversity, to facilitate freedom of movement and access and opportunity.

This project is not new. City making is an ancient art, with a massive pedigree and history. From our vantage point in the early decades of the 21st century, we can survey successes and failure of urban design and development, and come to some firm conclusions, to articulate principles of urban design that are fundamental and beyond question.

The principles most critical to our discussion today are:

- The importance of public space to the social and democratic health, civility of the community

- The centrality of the street as the simultaneous organizing element of the city and the most critical public space for the daily life of its citizens, providing freedom of movement, access, and connection.

- Density must be managed and molded artfully to clearly delineate and make distinct public and private space in the city.

These principles need to be applied to Jay Street and Downtown Brooklyn as the foundation for its transformation to a more significant urban quarter of a city likely to blow past a population of 10 million in the coming decades.

This part of Brooklyn started it urbanization in the 1830’s. (confirm) Up to this point the pattern of development started in an organic manner, probably following pathways and trails established by native inhabitants, where the major pathway connecting clusters of homes and burgeoning villages in the heart of what is today Downtown Brooklyn followed a logical path through the topography and lead to the important destination of the ferry crossing to Manhattan island at Fulton Landing. The pathway today, Old Fulton Street and Cadman Plaza East, marks the edge of Brooklyn Heights as a wide street with portions with heavy traffic.

The concentration of density started logically along this main street at the ferry landing. This pattern of urbanization matched the earlier beginnings of New Amsterdam and New York across the East River. But both urban patterns would be fundamentally altered by the Commissioners of 1811, when the pure grid iron organization of a street system at right angles was sanctified and imposed on the land. This organization at the time only applied to the urban organization of the unbuilt areas of Manhattan north of Houston, but clearly this grid became the instrument of urbanization of rural land. Fortunately in Brooklyn, this gridded structure was adjusted locally to some degree to existing conditions, either property ownership, geography, topography, or existing pathways, and any combination of these.

Thus we can see the grid as the fundamental structure of the streets and blocks of Downtown Brooklyn in the 19th century. At this point, consistent with the attitude expressed by the 1811 commissioners in New York, we do not see evidence of a strategy for broader public spaces in the growing urban center of Brookyln other than the streets themselves. Parks and other open spaces were defined over time, but not as part of a systematic, comprehensive plan. Some open spaces did emerge at the points where the shifted grids met, which is a common starting point for urban spaces in cities around the globe that have similar shifted grids. In this way the rise of Brooklyn urbanistically through the early 20th century was consistent with most US cities. While some American cities started with a clear strategy for defining public space, including New Haven, Philadelphia, Savannah, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn like New York saw a haphazard development of public space.

The grids at this point in time allowed this shoulder of Brooklyn to densify. The rural landscape was erased and ploughed under. Beyond the remains of the historic street of Old Fulton, not much hierarchy is apparent in this stage of urban development, likely resulting in a flow of people and transit throughout the tight network of streets. This network was established in the mid-19th century, and remained in place largely intact until the mid 20th century.

A well formed network of streets provides a strong connectivity between neighborhoods, allowing the critical freedom of movement to facilitate economic and social activity. Where this network is interrupted, this freedom of movement is significantly hindered. The cause of the interruption is sometimes geographic (a significant change of topography or a river or stream), but is often infrastructure, which in the 19th century might be a rail line or an industrial use that consumes a vast amount of land, and in the 20th century the same as well as highways and broad boulevards or urban blight.

From the early days of its urban development, this shoulder of Brooklyn was partially cut off from the northwest neighborhoods by a large infrastructural element, the Navy Yard. This left Vinegar Hill as an edge neighborhood of Downtown Brooklyn and its waterfront. The Navy Yards separation of Downtown Brooklyn from South Williamsburg places more emphasis on the roads south of the Navy Yard that connect western Brooklyn neighborhoods to the heart of Downtown. The other significant infrastructural element in this part of Brooklyn was the bridge that was needed to make the connection to Manhattan much stronger and efficient than the ferry service.

The Brooklyn Bridge’s alignment and elevation necessitated changes to the street grid in its way, and this was the first in a series of interventions that disrupted the street network in this critical urban center of Brooklyn.

But an important change of thinking about urban design emerged in the early 20th century and this new approach had a devastating impact on neighborhoods in Brooklyn, including Downtown. This new thinking on making cities, largely defined by Le Corbusier in his writing and vision for the city of tomorrow, as well as his proposals for Paris and New York, rejected the street as the fundamental organizing element and public space of the city. His planning approach placed a major emphasis on open space with buildings spread wide apart with a network of infrastructure of highways connecting them.

This strategy found a welcome audience in the US, with the growing domination of motor vehicles for transportation. With the motor car, came a need for new infrastructure. The focus on this new network of infrastructure resulting in a de-emphasis on the centrality of the street, and with it a loss of emphasis on modes of transportation other than motor vehicles. Street cars were quite broadly removed from the streets across the country to make room on the roads for cars.