Table of Contents

Acids and Bases

We can call any compound that adds H+ ions (a free proton) into solution an acid. Along with this, we would expect that any compound that would decrease the concentration of free H+ of a solution as a base. pH is the power of H+ of a solution. We define this power as a molar concentration of H+ in solution. This concentration invariably ends up being a relatively small number (though great in absolute numbers) and is expressed as a decimal number. Because the range of the concentrations is so great, we express these numbers as logarithmic numbers to avoid writing many 0’s after the decimal and to facilitate communicating the concentration. Since these numbers are so (relatively) small, we use the negative logarithm to describe this concentration.

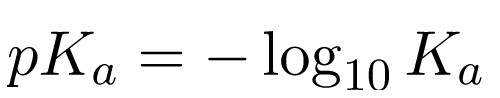

Mathematically defined,

The pH scale ranges so that anything below pH 7 is acidic and anything above pH 7 is alkaline. So a smaller number is more acidic. But didn’t we just state that something acidic contains more H+ ions? Remember, because we are dealing with a negative logarithm, this means the concentration is higher.

Logarithmic Scales

If we have a quantity that is 102, we know that translates into 100. Just as if we have a quantity of 104, we know that translates into 10000. Just as it becomes inconvenient to keep writing all those 0’s, it’s really impractical to write many many 0’s after a decimal. It’s really hard to talk about too! So we likewise will express numbers like 0.0001 as 10-4. A logarithm is the reverse function of an exponent. Therefore:

So how do we define a solution that is pH 2? Well, we already decided that this solution is below pH 7 — making it an acid. But what does this mean in terms of H+ ion concentration?

Let’s work this out algebraically:

Let’s bring the (-) over to the other side

Now let’s reverse the Log → base 10

Plug in the pH → molar concentration of [H+]

As we can now see, a solution of pH 2 is acidic because the molar concentration of [H+] is 10-2mole/L or 0.01M

Dissociation of ions: That number is small!

It’s not a small number. Remember that a mole is 6.022 X 1023. That’s a very large number! Think about it! A solution of pH 4 is acidic, but if we plug in the formula, we realize that this is equal to 0.0001M H+ – less than pH 2 at 0.01M!

But let’s compare it to the [H+] content of H2O. Now I’m going to sound crazier! Water can be thought of as being in an equilibrium where some of the molecules are ionizing and deionizing. We can express this in 2 ways:

- H2O ⇋ H+ + OH–

- 2H2O ⇋ H3O+ + OH–

So at any given point, a liter of H2O at neutral pH (7) has 10-7 moles of H+ ions. Incidentally, it also has 10-7 moles of OH– in solution. The second expression indicates the formation of a hydronium ion (H3O+) instead of a free proton in solution. So something that is pH 2 is a stronger acid than pH 4, right? Nope. That just indicates the amount of free protons in solution. It is more acidic but acid strength means something else. When we talk about strong acids, it means that it is more likely to donate a proton to the solution because it is more likely to ionize. Let’s look at the following:

- HA ⇋ H+(aq) + A–(aq) Where HA is an acid dissociating in solution

If this dissociation is very high, then we say that it is a strong acid. Similarly, a compound like NaOH readily dissociates completely in solution and provides OH– ions that can readily remove H+ from solution –a strong base! We speak of dissociation in terms of rates and we express this as the acid dissociation constant, Ka. This is calculated using the concentrations of [H+] (proton), [A–] (conjugate base) and [HA] (non-dissociated) at equilibrium:

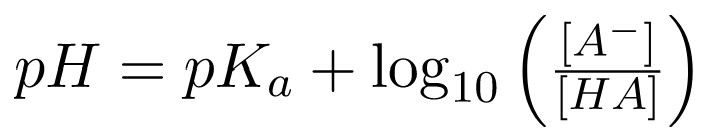

Just like the orders of magnitude we have when discussing pH, the rates of dissociation are more conveniently communicated on a logarithmic scale.

Think about it this way, if the concentration of the dissociated ions is very high, the numerator in the rate is very high → Ka is great. In other words, at equilibrium, the dissociation reaction looks more unidirectional than bi-directional as the compound is readily ionized:

- HA → H+(aq) + A–(aq)

On this scale, we refer to anything with a pKa < -2 as a strong acid since it will readily dissociate in solution. This form of the dissociation constant is extremely useful in estimating the pH of buffered solutions and for finding the equilibrium pH of the acid-base reaction (between the proton and the conjugate base). We can estimate the pH by utilizing the Henderson-Hasselbalch Equation:

Buffered Solutions

A buffer is something that resists change. A buffered solution is one that consists of a weak acid or weak base that will control the pH of a solution. Imagine a buffer to be a reservoir of available H+ or OH– ions. If a buffered solution is pH 2, adding a basic solution to it will not cause a drastic change to the pH because the reservoir of H+ will continuously neutralize the base. Eventually, this store or reservoir of H+ will be depleted. When this happens, the pH will suddenly change.

The range in which acid or base is added without a significant change in pH is called the buffered zone or the buffering capacity. When this store of H+ or buffering capacity is expended, we have reached the equivalence point that describes the point at which the base has completely neutralized the weak acid.

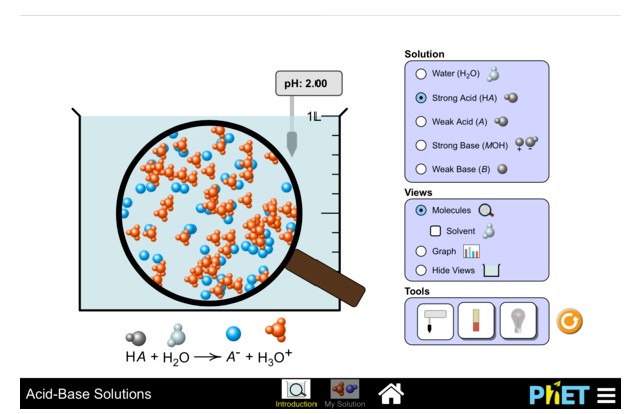

Practice: Acids and Bases Simulation

Use the following simulation to explore the types and quantities of molecules found in solutions of different pH values.

Practice: pH Simulation

Use the following simulation to explore the pH values of different solutions.

Titration Calculations

You can use the following formula to determine unknown volumes or concentrations involved in a titration:

MAVA = MBVB

where MA is the molarity of the acid, VA is the volume of the acid, MB is the molarity of the base, and VB is the volume of the base.

Titration Calculation Example #1

What volume of 0.25 M KOH is required to completely neutralize 60.0 mL of 1.0 M HNO3?

Solution: First, write down what you are given in the question.

Next, plug the numbers into the equation and solve.

So, 240 mL of 0.25 KOH is required to neutralize 60.0 mL of 1.0 M HNO3.

Titration Calculation Example #2

In a titration experiment, 53.7 mL of 0.50 M NaOH was required to completely neutralize a 100. mL sample of HCl. What was the molarity of the acid?

Solution: First, write down what you are given in the question.

Next, plug the numbers into the equation and solve.

So, the molarity of the acid was 0.27 M.

Print this page