Table of Contents

Writing the Rules of Heredity

In the mid 1800’s, an Augustinian friar named Gregor Mendel formalized quantitative observations on heredity in the the pea plant. He undertook hybridization experiments that utilized purebred or true breeding plants with specific qualities over many generations to observe the passage of these traits. Some of these physical traits included: seed shape, flower color, plant height and pod shape.

The pea plant (Pisum sativum) offered a great advantage of being able to control the fertilization process and having large quantities of offspring in a short period of time. In a simple experiment of tracking the passage of a single trait (monohybrid cross) through multiple generations, he was able to formulate rules of heredity.

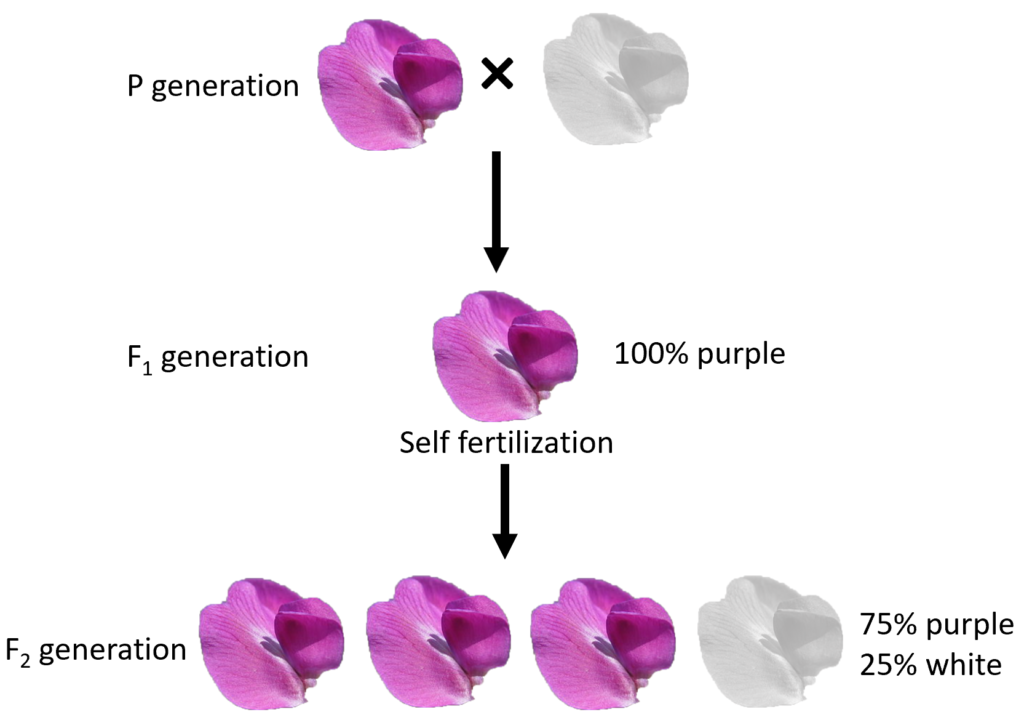

One example of a trait that Mendel studied is flower color. Mendel noted that pea plants either produced white flowers or purple flowers for many generations. He called these plants true breeding and used them as the first breeding pair or the parental generation (P). By removing the male parts of the pea flower (anthers containing pollen), Mendel was able to control for self-pollination. The hybridization came from applying the pollen from one true breeding plant to the female part (the pistil) of the opposite true breeding plant.

The subsequent offspring are referred to as the first filial generation (F1). In the first generation, all flowers are purple. Permitting self-pollination in the F1 generation leads to a second filial generation (F2). This generation sees the re-emergence of the white flowered plants in an approximate ratio of 3 purple flowered to 1 white flowered plants.

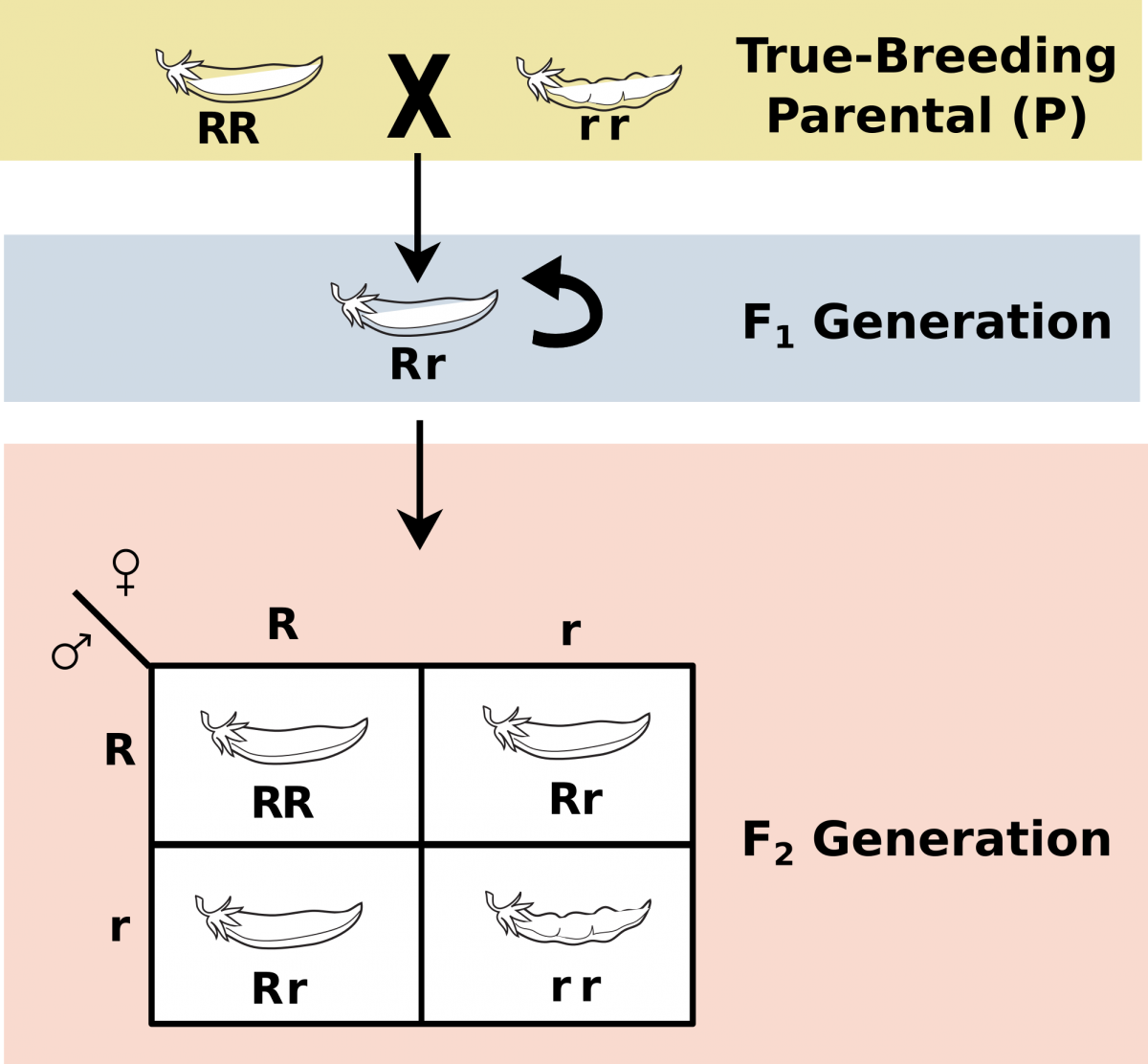

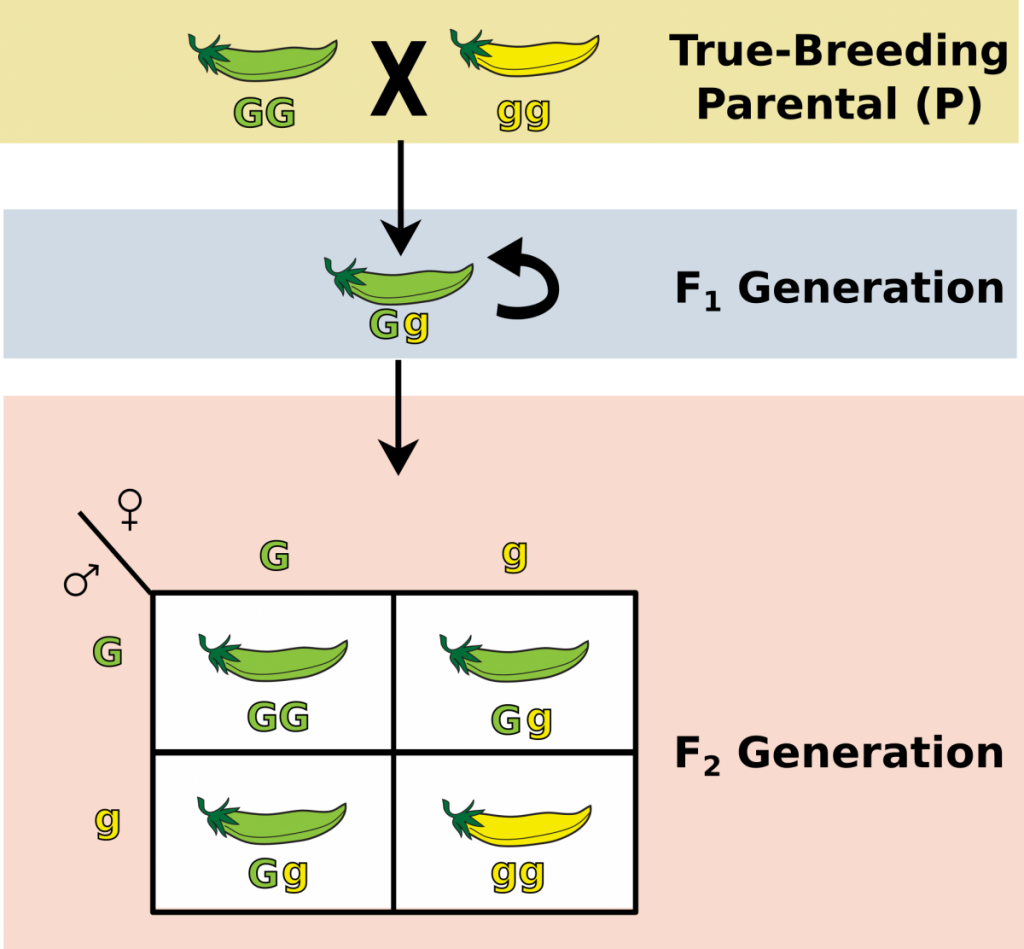

The loss of one variant on the trait in the F1 plants and the re-emergence in the F2 prompted Mendel to propose that each individual contained two hereditary particles where each offspring would inherit one of these particles from each parent. Furthermore, the loss of one of the variants in the F1 was explained by one variant masking the other, as he explained as being dominant. The re-emergence of the masked variation , or recessive trait in the next generation was due to the both particles being of the masked variety. We now refer to these hereditary particles as genes and the variants of the traits as alleles.

Mendel’s Rules of Segregation and Dominance

The observations and conclusions that Mendel made from the monohybrid cross identified that inheritance of a single trait could be described as passage of genes (particles) from parents to offspring. Each individual normally contained two particles and these particles would separate during production of gametes. During sexual reproduction, each parent would contribute one of these particles to reconstitute offspring with two particles. In the modern language, we refer to the genetic make-up of the two “particles” (in this case, alleles) as the genotype and the physical manifestation of the traits as the phenotype. Therefore, Mendel’s first rues of inheritance are as follows:

- Law of Segregation

- During gamete formation, the alleles for each gene segregate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene.

- Law of Dominance

- An organism with at least one dominant allele will have the phenotype of the dominant allele.

- The recessive phenotype will only appear when the genotype contains two recessive alleles. This is referred to as homozygous recessive.

- The dominant phenotype will occur when the genotype contains either two dominant alleles (homozygous dominant) or one dominant and one recessive (heterozygous).

Monohybrid Crosses (Single Trait Cross)

The Punnett square is a tool devised to make predictions about the probability of traits observed in the offspring in the F2 generation and illustrate the segregation during gamete formation.