Reflection

The United States is currently experiencing an opioid crisis as we witness a rapid increase in the prescription rate, and therefore usage of prescribed and non-prescribed opioid drugs. The consequence of the opioid crisis is deadly, and immediate countermeasures are needed by the federal and local government to curb the current trends of this disaster.

This research was very insightful as I have gained clinical knowledge that will help during medical history and intraoral and extraoral examination for patients using an opioid drug. For example, during medical history, the dental hygienist should question patients who disclose using an opioid drug to make sure there is no indication of overdose. The dental hygienist should focus on the patients’ response and how they communicate to ensure the patients answer to questions aligns with the signs and symptoms of the drug they are prescribed. There are also signs and symptoms that the dental hygienists look for in patients who did not disclose to using an opioid drug but is suspicious. Patients who abuse opioids will have a pinpoint-like pupils and moderate to severe xerostomia and generalized decay from the xerostomia which can make the patient more susceptible to caries and periodontal disease due to the reduced salivary flow. Other indications such as puffy face, tremors, smell of substance on breath, increase heartbeat and blood pressure will be noticeable during routine examination.

I really enjoyed this research paper because it goes to show that the dental hygienist is very important not just in caring for patients but also in helping curb substance abuse through identifying and reporting patient suspected of overdose.

This research paper examine the opioid crisis and regional parameters in the Midwest, specifically in North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Nebraska.

Research Paper

Opioid Crisis In The Midwest (North Dakota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Nebraska)

Narayani Dhanraj

Damasco

December 2018

Regional Parameters

The misuse of legal and illegal drugs has been around for a long time, and with the release of newer and more potent drugs, came the rise in abuse and fatalities. In the nineties, dentists were the number one prescribers of opioids, accounting for over 15.5% of all prescriptions (Somerman & Volkow, 2018). Since then, dentists cut their rate of opioid prescription writing by nearly half that amount. However, the opioid crisis remains at an all-time high.

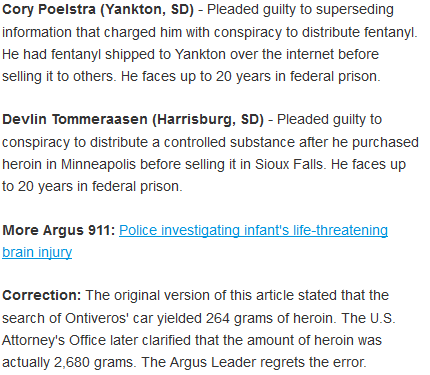

In the Midwest region that we were assigned, the state-prescribing rate of opioids for 2017 were slightly less than the national average of 58.7 per 100 persons (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). For example, state-prescribing rate of opioids for Nebraska and Wisconsin in 2017 were 56.6 and 52.6 per 100 persons, respectively (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Comparatively, the highest state-prescribing rate for opioids was in Alabama with 107.2 per 100 persons (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). In 2016, the average rate of abuse for opioid related overdose deaths at the state level in the Midwest were also below the national rate of 13.3 deaths per 100,000 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018a). Of the states in that region, only Wisconsin had a higher opioid overdose rate, 15.8 deaths per 100,000 persons, than the national rate (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018a). In fact, there was a 15-fold increase in opioid overdose death rate in Wisconsin from 1999 to 2016, from about 1.0 to 15.8 per 100,000 persons (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018a).

The primary drug of abuse in most of the Midwest states is marijuana. Also known by street names like weed, pot and grass, marijuana has various commercial brand names such as Kush, Haze and Diesel among others (Schleuss, 2014). “Marijuana is classified in the US as a Schedule I drug which, like heroin, contains substances with a high potential for abuse” and addiction (Oberbarnscheidt & Miller, 2016). According to an article published in the Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, “marijuana affects the same reward systems in the brain as alcohol, cocaine and opioids … [by] induc[ing] the release of endorphins … [and by] act[ing] as a dopamine agonist in the brain” (Oberbarnscheidt & Miller, 2016). The brain and spinal cord are the main sites of actions for marijuana. According to Oberbarnscheidt & Miller (2016), marijuana “binds to two types of G-protein-coupled receptors, CB1 and CB2.” As a result, “marijuana alters the user’s perceptions and mood and disturbs memory function and learning and leads to impaired judgment” (Oberbarnscheidt & Miller, 2016).

While marijuana is not federally recognized as legal, it is legal in some states and it does not have a lethal potency. The more concerning data for the Midwest region is the continued rise in opioid deaths and abuse. Across the U.S. from 1999 to present, the drug death rate has almost quadrupled, from 16,849 opioid related deaths in 1999 to 63,632 deaths in 2016 (Hedegaard, Warner, & Miniño, 2017). According to Hedegaard et al. (2017), “the rate of drug overdose deaths involving natural and semisynthetic opioids, which include drugs such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, increased from 1.0 in 1999 to 4.4 in 2016. Hedegaard et al. (2017) also pointed out that “the rate increased on average by 13% per year from 1999 to 2009 and by 3% per year from 2009 to 2016.”

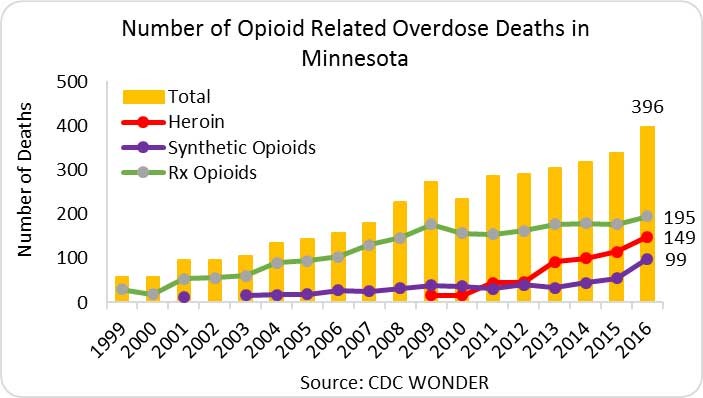

In the Midwest, prescription opioids are the leading cause of deaths related to opioid overdose compare to Heroin and Synthetic Opioids. In fact, Wisconsin and Minnesota, prescription opioids accounted for 45% and 49% of opioid overdose deaths, respectively (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018a; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018b). See Appendix A for prescription opioid related deaths. It is the misuse of prescription medications that ultimately trickle into the community and lead to the accessibility of drugs. In fact, most of the drugs that are abused originated from doctors’ offices. According to a consumer protection report, “27% obtained the drugs with their own prescription, but 26% got them illegally from a friend or relative for free” (Bennett, 2017). Furthermore, “twenty-three percent bought them from a friend or relative, and 15% bought them on the street from a drug dealer” (Bennett, 2017). Based on the report, “64% of those who were abusing the drugs, were not actually prescribed the pills legally” (Bennett, 2017). Aside from prescription, those who develop an addiction to opioid tend to acquire them illegally from drug peddlers.

There is a correlation between opioid abuse and socioeconomic status. According to the CDC, “opioid-involved overdoses accounted for two thirds of drug overdose deaths, with increases across age and racial/ethnic groups, urbanization levels, and in numerous states” (Seth, School, Rudd, & Bacon, 2018). The article continues that the Midwest recorded the highest rates of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths (Seth et al., 2018). There is a clear correlation between opioid abuse and people in poor regions. As the National Institute on Drug Abuse states, “people on Medicaid are more likely to be prescribed opioids, at higher doses, and for longer durations—increasing their risk for addiction and its associated consequences” (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2017).

Although a correlation exists between poverty and opioid abuse, addiction to opioids like heroin affect people regardless of socioeconomic factors such as income, education or employment. According to an article published by Sunrise House- an American Addiction Center, “the CDC reports that the greatest increase in heroin use since 2002 has occurred among demographic groups that have had traditionally low levels of use, including women, Americans with higher incomes, and people who have health insurance coverage” (“Addiction within Demographics”, n.d.). The article also states that “a comparison of figures from 2002 to 2013 from the CDC shows that heroin use increased the most in Americans with an average household income of $20,000-$49,000 (an increase of 77 percent), while the increase in use in Americans with an income over $50,000 and in those with an income of $20,000 or less was very similar (60 percent versus 62 percent)” (“Addiction within Demographics,” n.d.).

Furthermore, deaths resulting from opioid overdose in the Midwest are concentrated in white, non-Hispanic males between the ages of 25-34 demographic (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016a; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016b). Based on the data presented in the Kaiser Family Foundation (2016b) report, white, non-Hispanic accounted for 83% and 78% of opioid overdose deaths in Wisconsin and Minnesota, respectively. Furthermore, the 25-34 age range accounted for 28% and 27% of opioid overdose deaths in Minnesota and Wisconsin, respectively (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016a). This was the highest in comparison to the other age group in the report.

Each state has incorporated their own strategies for dealing with the opioid crisis. Wisconsin has been given a grant focusing on reducing the nonmedical or unauthorized availability prescription opioids, as well as preventing opioid-related overdose deaths (Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2018). North Dakota has a program called “Lock. Monitor. Take Back,” with the primary goal of reducing access to prescription drugs (North Dakota Prevention Resource & Media Center, 2018). Minnesota was chosen to participate in the NGA prescription drug abuse academy (Minnesota Department of Health, n.d.). While Nebraska is working proactively to combat their crisis by utilizing the “The Prescription Drug Monitoring Program” as well as passing a mandatory reporting law (Gage & Naughton, 2016). South Dakota developed South Dakota’s Statewide Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis in 2017 (South Dakota Departments of Health and Social Services, n.d.). There are also many counties that are opening triage centers as an initial point for those with both mental health and/or substance abuse issues. In Minnehaha County, South Dakota, local hospitals, law enforcement and mental health care providers are all working together to assemble a drop site so people can go to seek necessary treatment (Ammesmaki, 2018).

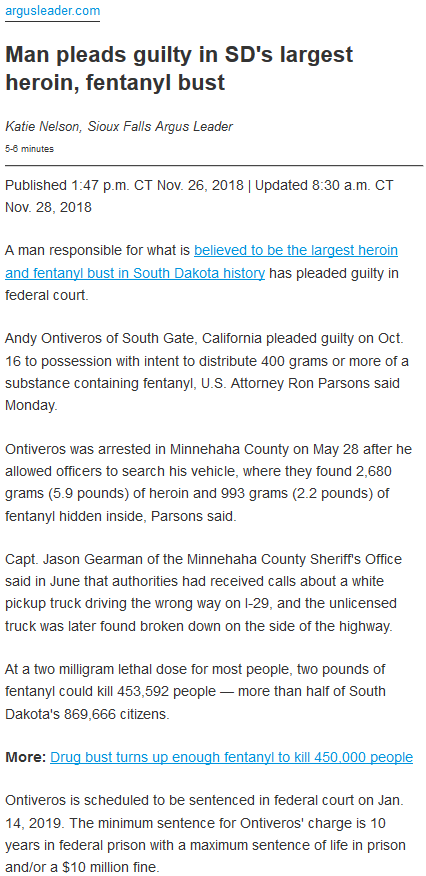

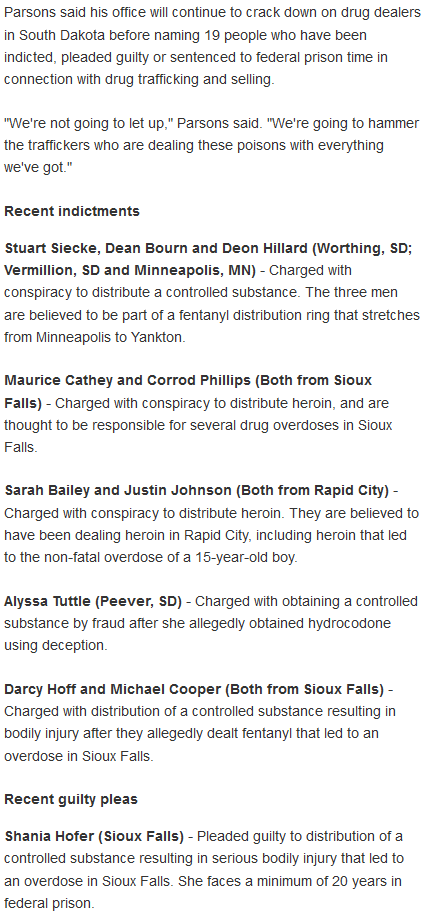

Impact Story

One major benefit the media has on opioid crisis is that it helps bring the issue of substance abuse to the front. Television and social media gives us the power to share important information about drug abuse in our community and across the country. Two recent news report from the Midwest shows the destructive and detrimental magnitudes of substance abuse in our country today. In the first article titled, “ND bartender accused of providing heroin that caused an overdose,” Herald (2018) reported that a bartender from Tioga, North Dakota was accused of selling heroin which resulted in a deadly overdose (see Appendix B for news article). Daniel Slaven, a 43-year-old man, purchased heroin from bartender, Piper Bjornsen, a 29-year-old woman. Slaven then returned home and injected the heroin. Later that day, police and EMT were dispatched to his home and Slaven was pronounced dead at the medical center. Bjornsen have a preliminary hearing scheduled for December 13, 2018. In the second article titled, “Man pleads guilty in SD’s largest heroin, fentanyl bust,” Nelson (2018) reported that a man pleaded guilty to what is alleged to be the biggest heroin and fentanyl raid in South Dakota’s history (see Appendix C for news article). Andy Ontiveros was arrested in Minnehaha County, South Dakota after officers “found 2,680 grams (5.9 pounds) of heroin and 993 grams (2.2 pounds) of fentanyl hidden inside” his vehicle (Nelson, 2018). Ontiveros will be sentenced in federal count on January 14, 2019. According to Nelson (2018), Ontiveros felony has a minimum sentence of 10 years to maximum of life in federal prison and/or a hefty fine of $10 million.

The aftermath of these events affected everyone from those directly involved in the incident to family and community members. In Daniel’s case, he lost his life as a result of using heroin. He is survived by his fiancé, three children, four siblings and his parents among many other family members and longtime friends (Haakenson, 2018). The impact of this tragic event is limited to those who knew Daniel. The event that Nelson reported in her article could have resulted in deadly impact of immense proportions had Ontiveros not been caught. It would have made it that much easier for teens and adults to have access to heroin and fentanyl. What does possession with intent to distribute 993 grams (2.2 pounds) of fentanyl means? To put this into perspective, “at a two milligram lethal dose for most people, two pounds of fentanyl could kill 453,592 people – more than half South Dakota’s 869,666 citizens” (Nelson, 2018).

These types of news reports are quite common in the Midwest. In fact, there have been five recent indictments and three guilty pleas concerning distribution of controlled substances like fentanyl and hydrocodone in South Dakota (Nelson, 2018). Anyone can get pulled into the realm of substance abuse. As Scala (2018) put it, “substance abuse is not racist, sexist, ageist or classist.” It irritates me to know that drugs peddlers are undermining the efforts and progress of those who are taking actions to curb the opioid crisis.

Looking back at Herald’s article, I do not believe there were any regional factors that could be attributed to the outcome of Daniel’ death. The median household income in Tioga, North Dakota, $58,478, is slightly above the national average of $57,617 (Data USA, n.d.). Tioga has a poverty rate of 4.9% which is well below the national poverty rate. The most common Bachelor’s Degree recipients are General Business Administration & Management, Teaching and Registered Nursing (Data USA, n.d.). Perhaps the outcome would have been different for Daniel if controlled substances wasn’t as readily available as sending a quick text message. Because of people like Ontiveros who are still roaming the streets, these substances are ubiquitous in the black market. The only silver lining from these reports is that authorities were able to eliminate “2,680 grams (5.9 pounds) of heroin and 993 grams (2.2 pounds) of fentanyl” from the streets of South Dakota (Nelson, 2018). That is most definitely an enormous victory in undertaking opioid crisis.

Role of Dental Hygienist

It is very important to acquire a thorough and accurate medical and dental history from all patients. However, dental hygienist should pay close attention to those patients suspected of abusing drugs. During medical history process, questions should focus on patients’ past and present “drug addiction, alcoholism, and substance abuse” usage (Scala, 2018). If patient is taking the required dose of prescribed opioid, the hygienist should still question the patients to evaluate how the medication affects the patient. According to Scala (2018), if the patients “list medications, inquire about them … if they don’t … [then] ask them to verify again. If they do check those boxes on their health history, reach out to them.” Dental hygienist should focus on patients’ response and how they communicate. Patients’ response to questions should align with the signs and symptoms observed by the hygienist.

Patients that misuse drugs often times exhibit signs that are indicative of substance abuse. For example, patients who abuse opioids will have a pinpoint-like pupils and “moderate to severe xerostomia … followed by generalized decay occurring from the xerostomia” (Scala, 2018). This can make the patient more susceptible to caries and periodontal disease because of the reduced salivary flow. There are some signs like poor appetite and insomnia that may not be visible during a dental appointment. However, other indications such as puffy face, tremors, smell of substance on breath, increase heartbeat and blood pressure will be noticeable during routine examinations (McFarland, Giannini, & Fung, 2018). Other intraoral indicators include oral lesions or ulcerations, oral candidiasis, stomatitis, leukoplakia, leukoedema, angular cheilitis and hyperkeratosis.

A comprehensive medical history and solid understanding of the signs and symptoms associated with substance abuse will help with developing an appropriate and tailored treatment plan. Determining if a patient is abusing drug is important because the abused substance can interfere with the patient’s treatment plan and direct care. For example, certain stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine may diminish the effect of local anesthetics. As a result, the patient “may require more local anesthesia during a dental procedure – though the maximum amount of local anesthesia that can be administered remains unchanged” (McFarland et al., 2018). If a hygienist was not aware that a patient is a drug addict or if the patient did not divulge their drug history, then the hygienist might not know that nitrous oxide analgesia should be avoided in “chemically dependent patients because it is a mood-altering drug and may increase the potential for further drug abuse by creating the same or similar pleasurable sensation” (McFarland et al., 2018). Treatment plan for these types of patients will require special practitioners with experience in caring for such patients.

In order for dental hygienist to educate patients on the effects of substance abuse, the hygienist must be well-informed on regional drugs usage and current trends at the service location. This way the hygienist will be able to identify intraoral markers of drug use, encourage patients to reach out to their primary care doctors or refer them to an addiction treatment specialist (McFarland et al., 2018). This is very important because patients who are not encouraged to seek treatment will do nothing and the “degenerative effects of continued drug use [will] increase the risk of hepatitis and HIV” (McFarland et al., 2018). Therefore, dental hygienist has a very important role not just in caring for patients but also in helping curb substance abuse. That said, this effort should start from the time the patients make their way to the dental chair to commence the medical history component.

References

- Addiction within Demographics: Evaluating an Individual’s Treatment Needs. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://sunrisehouse.com/addiction-demographics/socioeconomic-groups/

- Ammesmaki, G. (2018). Sioux Falls Sees a Rise in Opioid Deaths. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2018-08-04/sioux-falls-sees-a-rise-in-opioid-deaths

- Bennett, Michael. (2017). The Great USA Opioid Epidemic with Expert Insight. Retrieved from www.consumerprotect.com/opioid-epidemic/

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). U.S. State Prescribing Rates, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxstate2017.html

- Data USA. (n.d.). Tioga, ND. Retrieved from https://datausa.io/profile/geo/tioga-nd/

- Gage, T., & Naughton, J. (2016). DHHS Working to Combat Opioid Abuse. Retrieved from http://dhhs.ne.gov/Pages/newsroom_2016_june_opioid.aspx

- Haakenson, Marcella. (2018). Daniel Slaven. Tioga Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.journaltrib.com/articles/tribune-obituaries/daniel-slaven/

- Hedegaard, H., Warner, M., & Miniño, A. (2017). Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016, data brief no 294. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm

- Herald, W. (2018, November 14). ND bartender accused of providing heroin that caused an overdose. Grand Folks Herald. Retrieved from http://www.grandforksherald.com/news/crime-and-courts/4529404-nd-bartender-accused-providing-heroin-caused-overdose

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016a). Opioid Overdose Deaths by Age Group. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-age-group/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016b). Opioid Overdose Deaths by Race/Ethnicity. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- McFarland, K. K., Giannini, P. J., & Fung, E. Y. K. (2018, January). Addiction and Oral Health Care. Decision In Dentistry, 4(1). Retrieved from http://decisionsindentistry.com/article/addiction-oral-health-care

- Minnesota Department of Health. (n.d.). Opioid Misuse, Substance Use Disorder, and Overdose Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/healthimprovement/working-together/state-plans/opioidstateplan.html#Workgroups

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2017). Addressing the Opioid Crisis Means Confronting Socioeconomic Disparities. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2017/10/addressing-opioid-crisis-means-confronting-socioeconomic-disparities

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018a). Wisconsin Opioid Summary. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/wisconsin-opioid-summary

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018b). Minnesota Opioid Summary. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/minnesota-opioid-summary

- Nelson, K. (2018, November 26). Man pleads guilty in SD’s largest heroin, fentanyl bust. Argus Leader. Retrieved from https://www.argusleader.com/story/news/crime/2018/11/26/man-pleads-guilty-sds-largest-heroin-fentanyl-bust/2115282002

- North Dakota Prevention Resource & Media Center. (2018). Lock. Monitor. Take Back. Retrieved from https://prevention.nd.gov/takeback

- Oberbarnscheidt, T., & Miller, N. S. (2016). Pharmacology of Marijuana. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 8, 1-7. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000S11-012.

- Scala, C. (2018). Own your role in curbing addiction. RDH, 38(2). Retrieved from https://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-38/issue-2/content/own-your-role-in-curbing-addiction.html

- Schleuss, J. (2014). Marijuana’s many strains. Retrieved from http://graphics.latimes.com/marijuana-strains/

- Seth, P., School, L., Rudd, R. A., & Bacon, S. (2018). Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, Cocaine, and Psychostimulants — United States, 2015–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 349-358. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/pdfs/mm6712a1-H.pdf

- Somerman, M. J., & Volkow, Nora D. (2018). The role of the oral health community in addressing the opioid overdose epidemic. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 149(8), 663–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.06.010

- South Dakota Departments of Health and Social Services. (n.d.). Avoid Opioid Prescription Addiction. Retrieved from https://www.avoidopioidsd.com/about/strategic-plan/

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2018). Wisconsin State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis (STR): 2017-2018 Final Prevention Activity Report. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/library/p-02175.htm

Appendix A

Prescription Opioid Related Deaths in Wisconsin and Minnesota

Appendix B

Herald, W. (2018, November 14).

Appendix C

Nelson, K. (2018, November 26).