INTRODUCTION: Jay Street runs for approximately 14 blocks north to south from the East River in Dumbo to Fulton Street Mall in Downtown Brooklyn. Along this stretch of Brooklyn stand a courthouse, a cathedral, multiple college and university buildings, housing, office buildings, a hotel, warehouses, a city park, a high school. This stretch is also marked by parking lots, crossings over wide streets and an underpass below a bridge with significant noise pollution. Jay Street’s sidewalks are teaming with life along some blocks, and a no-man’s land along others. Pedestrians are often confused and disoriented on this street , not sure it will take them where they need to go. Urban renewal has left this portion of Brooklyn chopped up and left in a haphazard state , unplanned and lacking in many of the fundamental qualities that are found in thriving neighborhoods of New York City. This study is aimed to be a catalyst for change by establishing a vision that captures the potential of this unique urban precinct and illustrating a potential transformation through the design of the urban spaces (streets , squares, and parks) and architectural proposals for many of the critical sites of the precinct. This project responds to a request by the local business organizations that have established a new identity for this part of Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Tech Triangle. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Industrial Park, the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, and the Dumbo Improvement District have joined together to foster the continued growth of this precinct through initiatives and a branding effort. Tucker Reed, the President of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, astutely observed that urban renewal has left Jay Street as the only major corridor linking downtown Brooklyn to Dumbo and the Navy Yard. Yet Jay Street as it exists today does not serve well its critical role as a linking corridor. Instead, the conditions along Jay Street as well as in the broader precinct inhibit the natural flow of people and activity that is a critical requirement for the success of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle initiative. This study was initiated in the Urban Design Studio course (arch 4710) at The New York City College of Technology (Citytech) lead by Professors Duddy and Montgomery. The studio comprised of 12 students who worked on analysis and project proposals for new streets and squares, new in fill buildings, and critical changes to existing building fabric and lots. The students contributing to this project include:

Austin, Aleyda; Batista, Jennifer; Jimenez, Alma; Johnson, Corey; Karimov, Timur; Khan, Mohammed; Melnikova, Evgenia; Shelton, Tony; Sosa , Evgueni; Stelmach, Maciej; Whyte Benitez, Agata; Wilson, Camilla

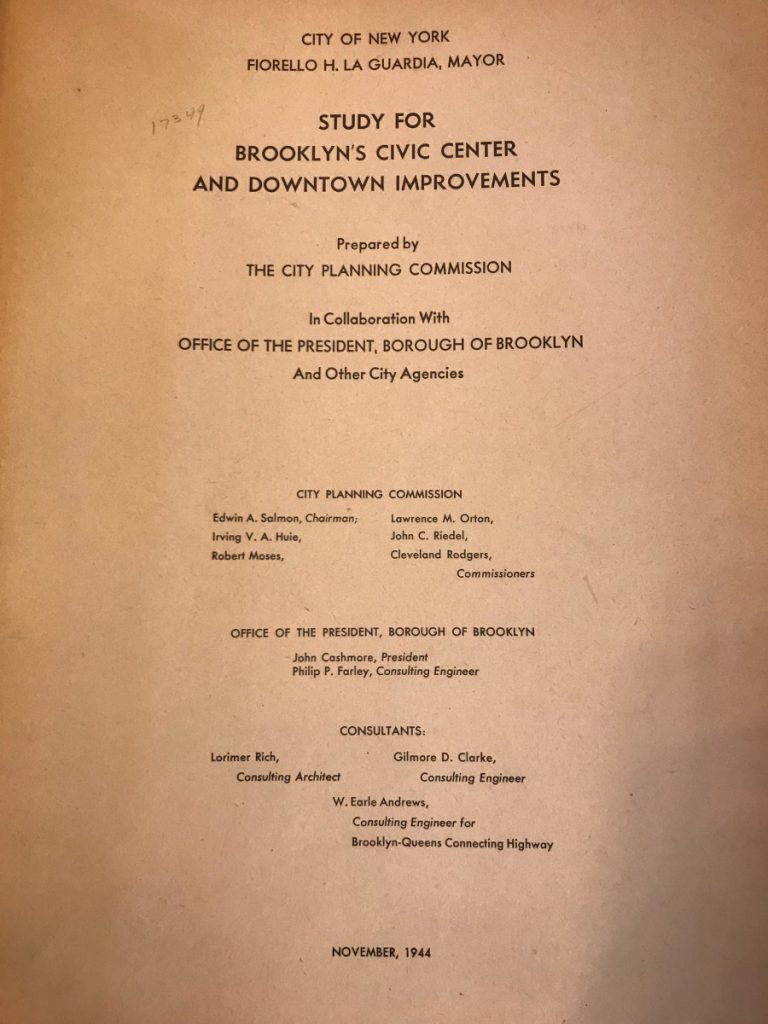

PUBLISHED DISCUSSION in BROOKLYN TIDES

Shepard, Benjamin Heim, and Noonan, Mark J. Brooklyn Tides : The Fall and Rise of a Global Borough. Urban Studies (Bielefeld, Germany). 2018.

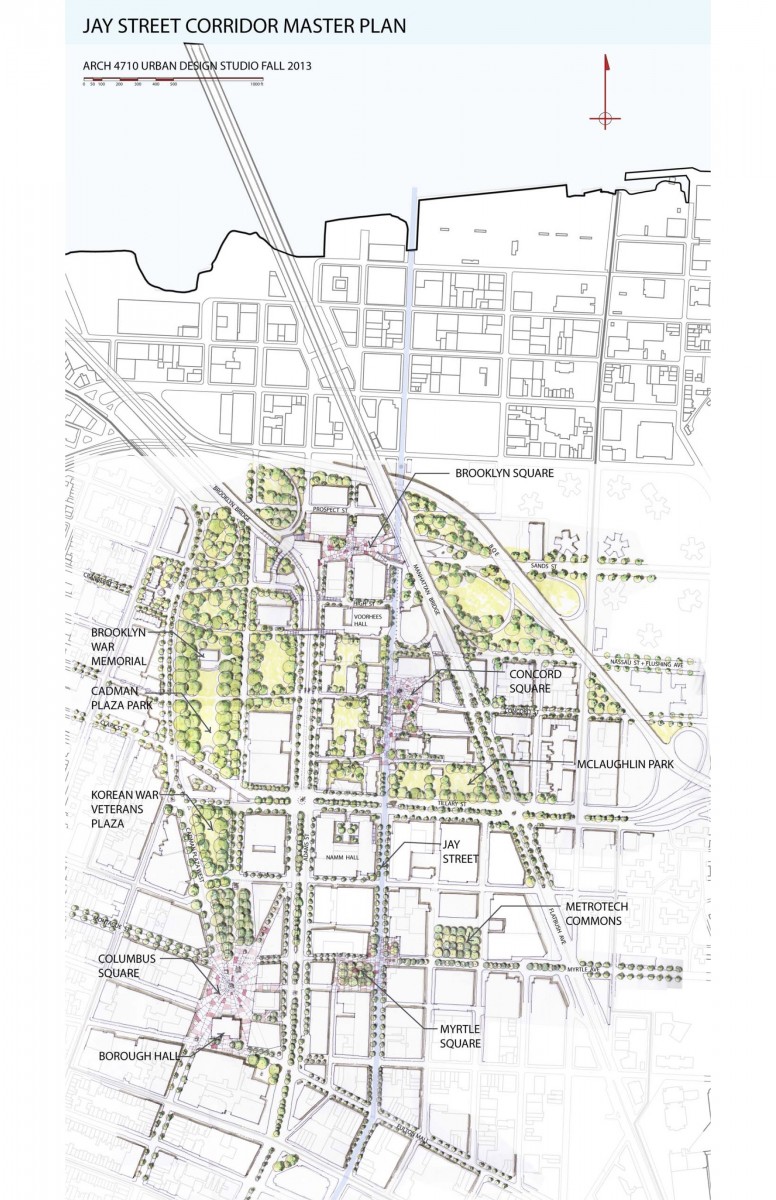

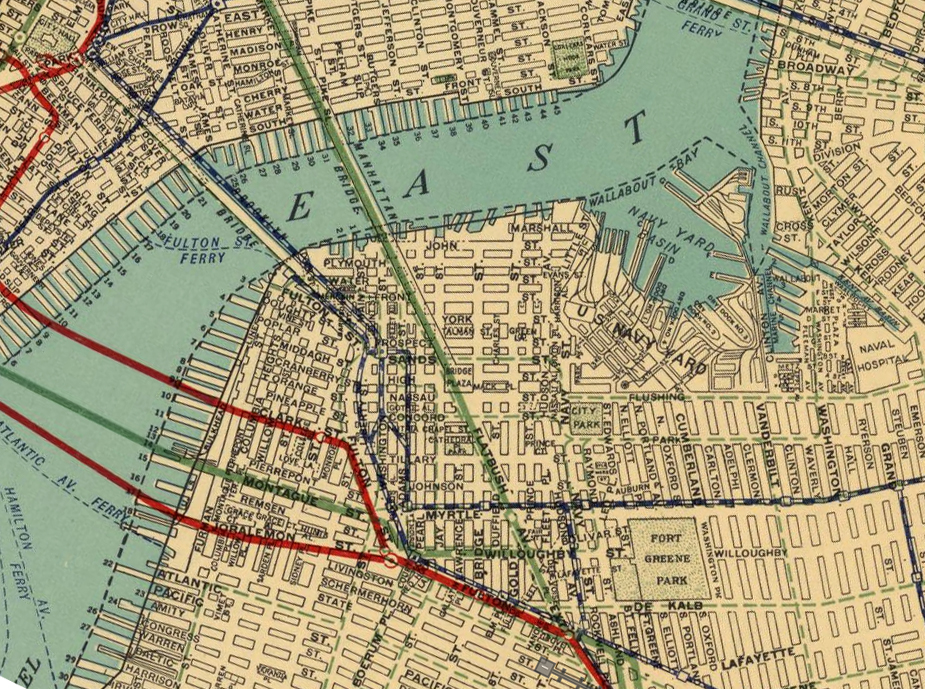

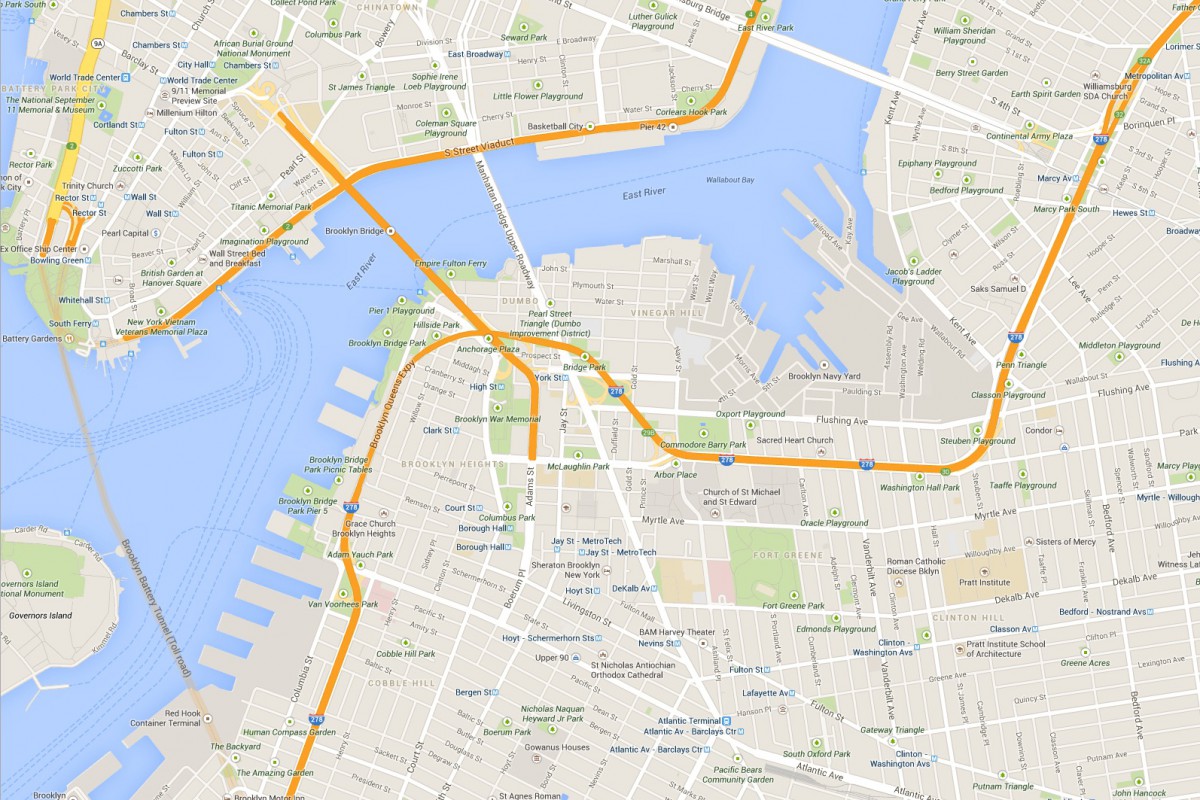

STUDY AREA: The precinct is a nexus of major transportation infrastructure, most obviously the convergence of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. The study area is the area considered to be strategically connected to the Jay Street Corridor. The area is not strictly conforming to the extent of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle. The study area is bounded by the East River to the north, Brooklyn Heights to the west, Atlantic Ave to the south, and Navy Street to the East. Jay Street’s prominence in the study area arises due to its role as the major north south roadway that connects Fulton Street to Dumbo and the East River waterfront. The study area is the nexus of the high aspirations for Downtown Brooklyn capitalizing on the emergence of the national and international recognition of the Brooklyn “brand.” Real estate pressure is building on the precinct with new residential towers, academic, and commercial buildings rising with increasing frequency. The precinct is a mixed use hub surrounded by predominately residential neighborhoods. The waterfront is in transition, with the development of Brooklyn Bridge Park along the Brooklyn Heights waterfront, continuing west along the Dumbo waterfront. A number of vacant land areas are found in this precinct. Some of these are vestigial areas surrounding the BQE, Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges. A significant number of vacant lots are currently used for surface parking. The Navy Yard stands prominently in the precinct as a commercial zone standing apart from the surrounding neighborhoods.

HISTORIC CHARACTER: The precinct is architecturally significant, with many significant historic structures, most significantly, the Brooklyn Bridge. The Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges have a dramatic impact on the streets and blocks where they merge into the neighborhood. They also dominate the skyline of the waterfront. The Bridges are a major gateway into Brooklyn for both city residents and tourists. The arrival in Brooklyn from both bridges is under whelming and confusing, delivering pedestrians into a no mans land without clear direction or accommodation.

CIVIC MONUMENTS: Downtown Brooklyn is a civic center, with key governmental offices and functions , including Borough Hall, State and Federal Courthouses. Downtown Brooklyn is also dense with Higher learning institutions, including Citytech, NYU Polytechnic, and a new Graduate Center for New York University. A large open space system from Borough Hall to Old Fulton Street includes two War Memorials. This open space sequence is dubbed the Brooklyn Commons.

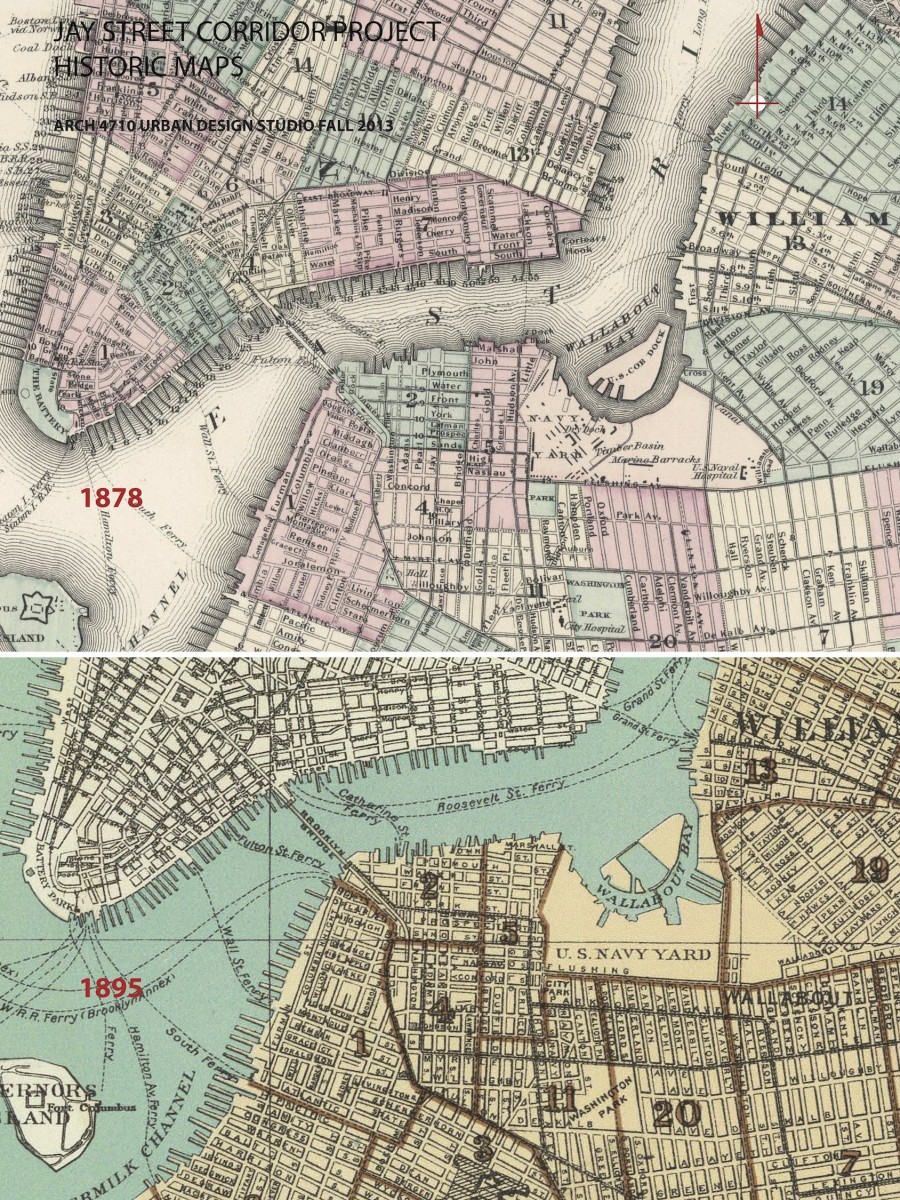

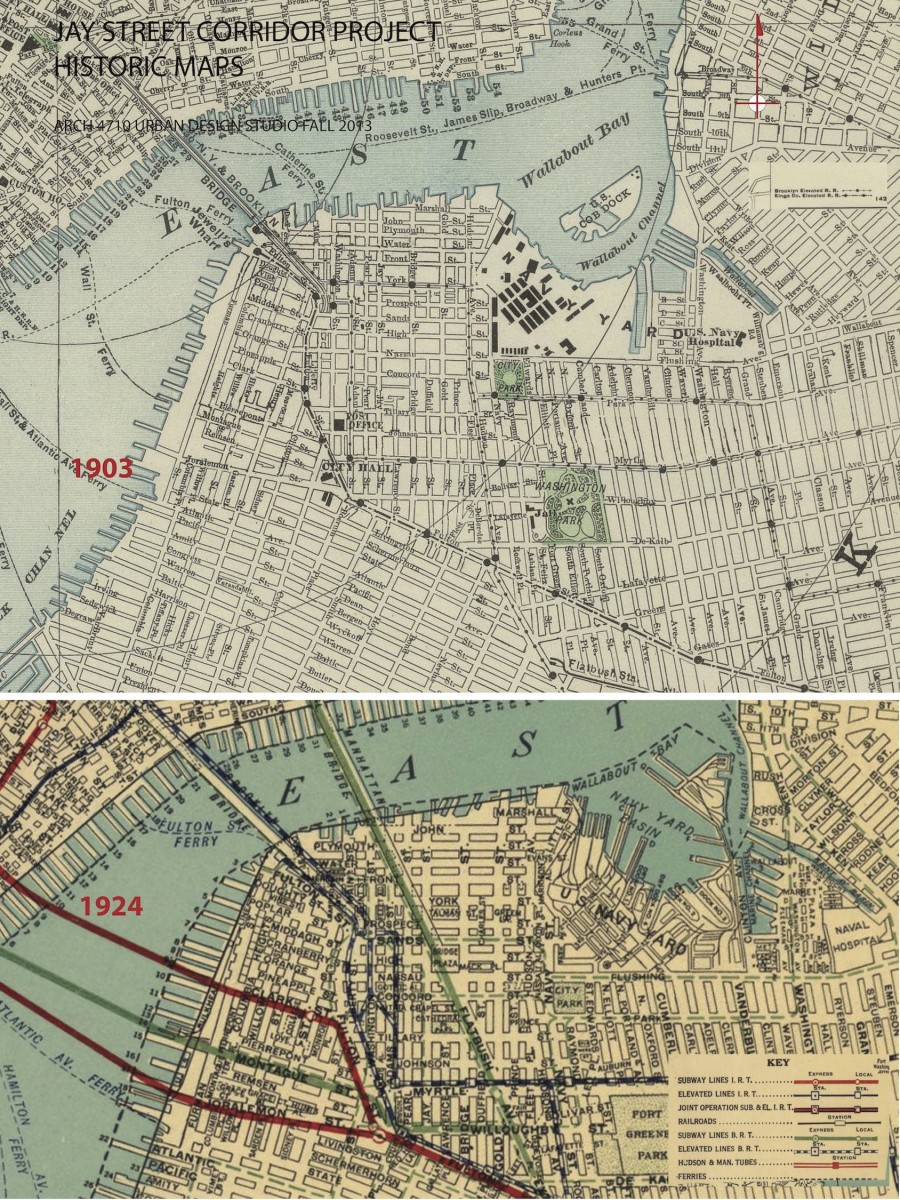

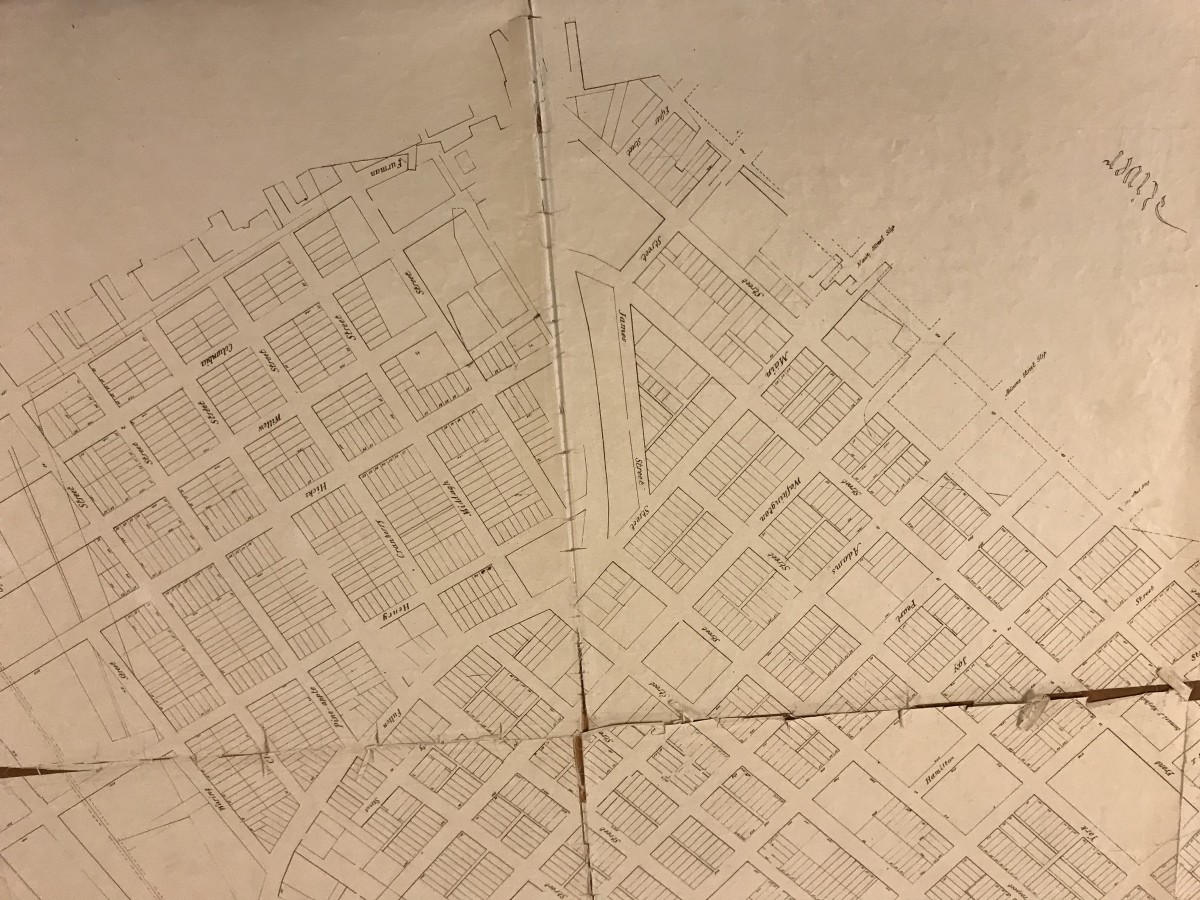

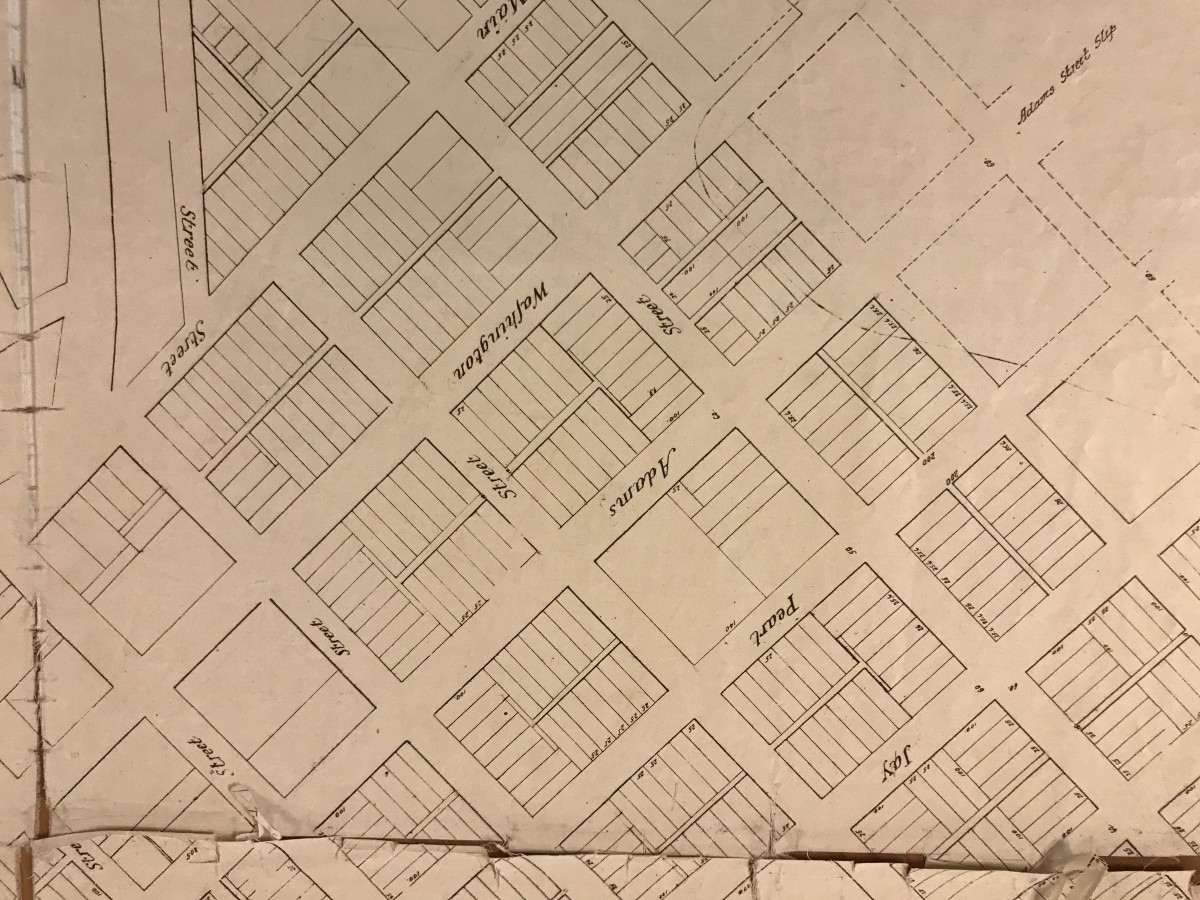

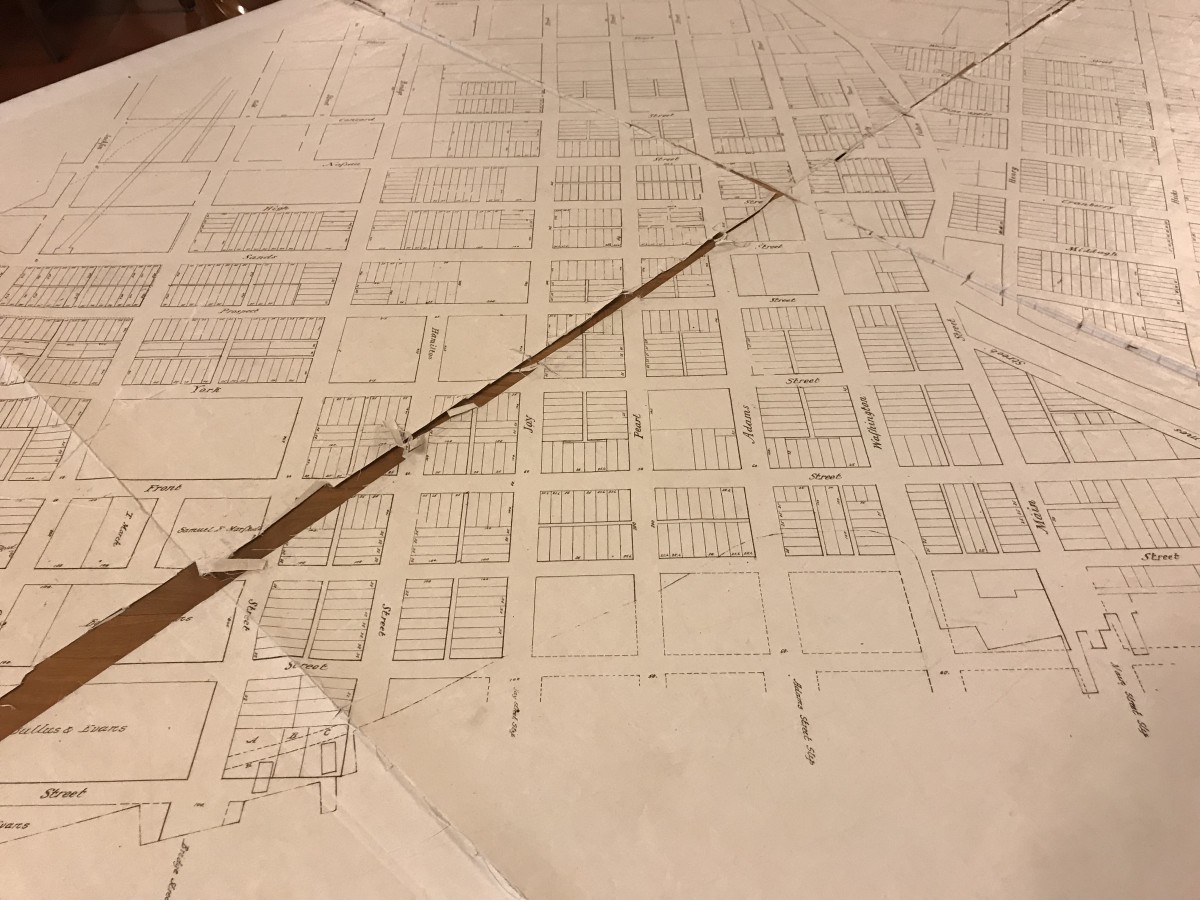

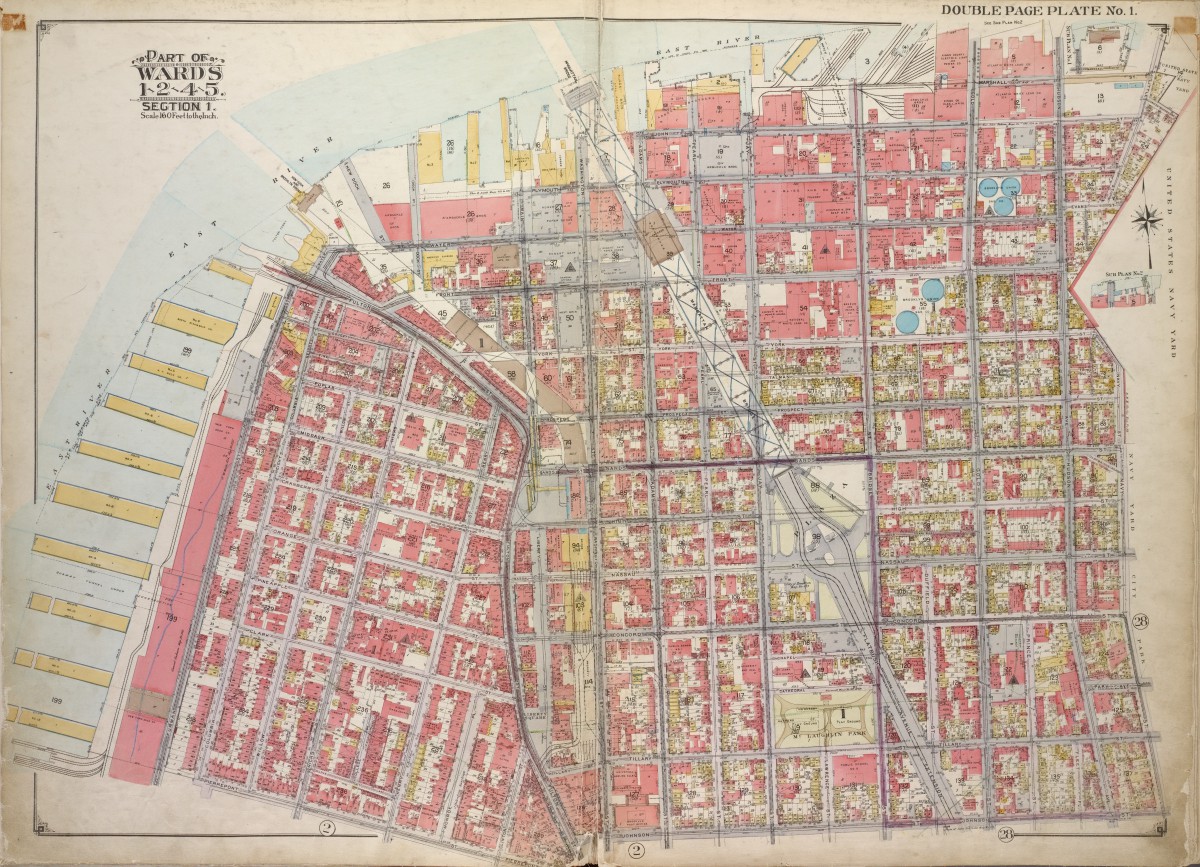

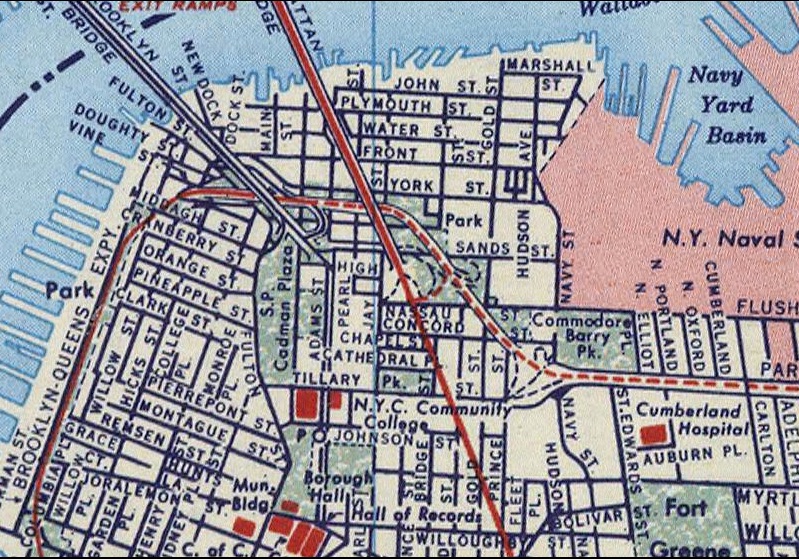

URBAN DEVELOPMENT / EVOLUTION: Historic maps illustrate the urban development and evolution of this part of Brooklyn. In the 18th century, organic roadway systems provided routes for commerce and communication from the countryside and small villages into the growing urban center on Manhattan island. The organic roadways responded to topography and other geographic features. The grid iron of streets and blocks that was firmly established for Manhattan in the 1811 Commissioners Plan is also implemented in Brooklyn in the early 19th century, with the same disregard for geographic features. Before the bridges were introduced, the focus of urban develop was Fulton Landing with a major ferry connection to Manhattan. The earliest major route to Fulton Landing was maintained as the modern Old Fulton and Cadman Plaza West road alignments. The early concentration of density and commerical activity was along the routes to the ferries, especially along Old Fulton Street in the area of Brooklyn Heights.

STREET NETWORK: There are a number of layers to the hierarchy of the street and roadway system in this precinct, including expressways, boulevards with divided lanes, wide streets with 4-7 lanes of traffic plus parking, typical local streets of 2-4 lanes plus parking. A number streets coming into the study area provide regional connectivity for motorists from Queens, Central and South Brooklyn, and Long Island. This precinct was fundamentally transformed by the bridge connections to Manhattan. The bridges converge of this small land area, resulting in significant demolition of fabric.

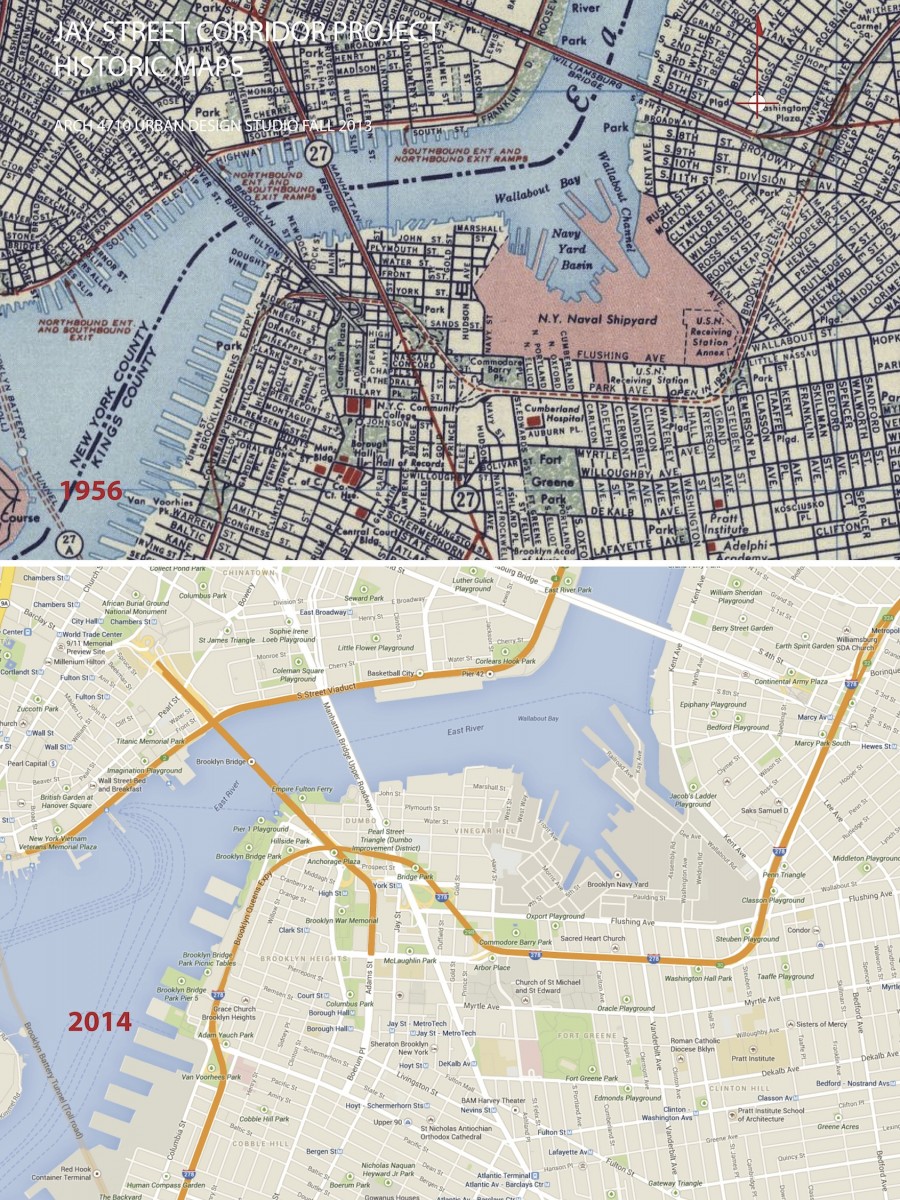

EAST-WEST ROUTES: Three major east west streets lead into the study area from the east. Myrtle Ave and Flushing Ave are historical connections to downtown Brooklyn from the distant Eastern neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens. Tillary Street connects to Park Ave as well as the BQE on the east, channeling significant regional traffic in and out of the precinct. The local commercial “main streets” of streets of Brooklyn Heights are Montague and Clark Streets. The historical maps indicate that Myrtle Ave once connected to Montague St providing a powerful connection from inland Brooklyn to the waterfront.

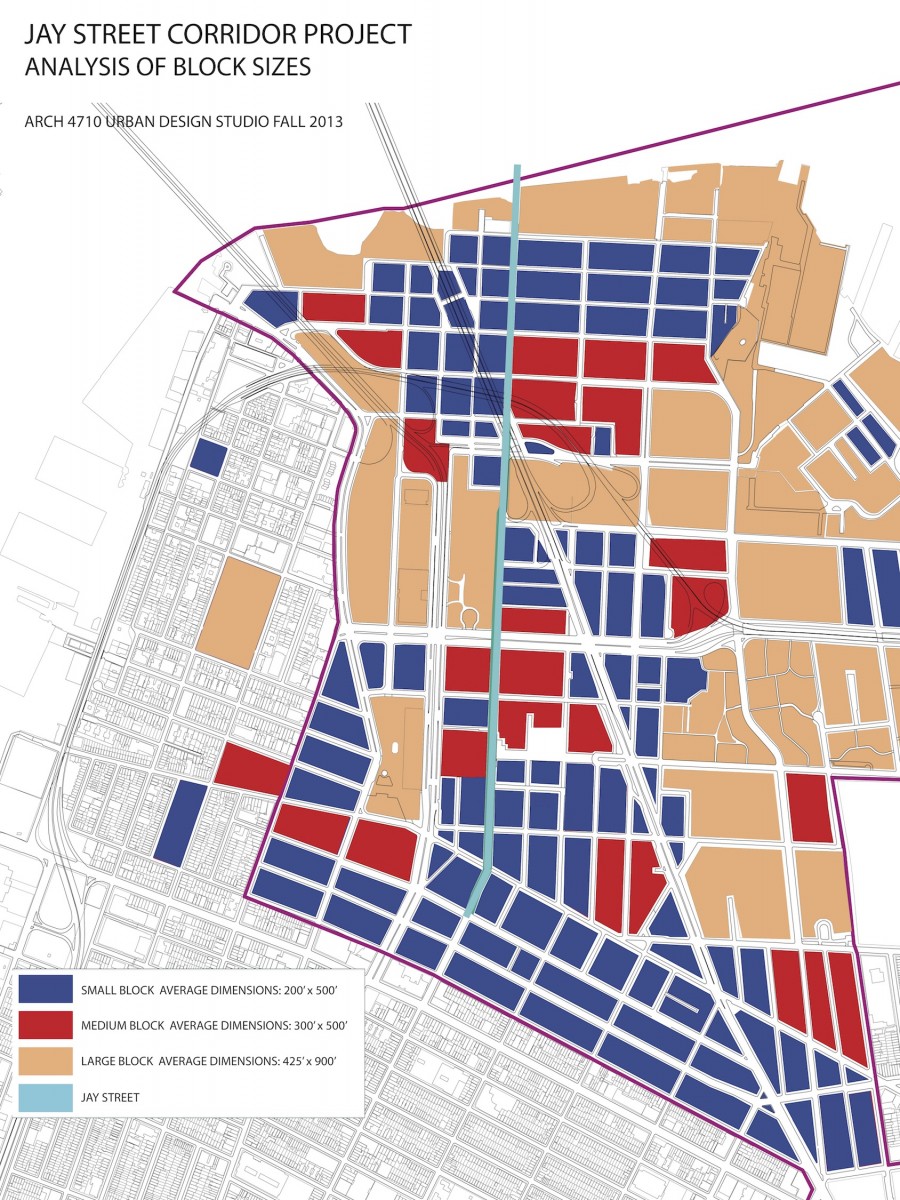

URBAN DISRUPTION: The obvious first observation for this urban precinct is the disruption to the urban structure by the multiple regional roadways and bridge infrastructure. The grid iron street network so apparent in the historical maps has been transformed into an irregular pattern of widely varying block sizes, cut off streets, and isolated areas. The disrupted urban structure sits geographically at the center of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle. A primary challenge of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle development strategy is to address this disruption of the urban structure at its core.

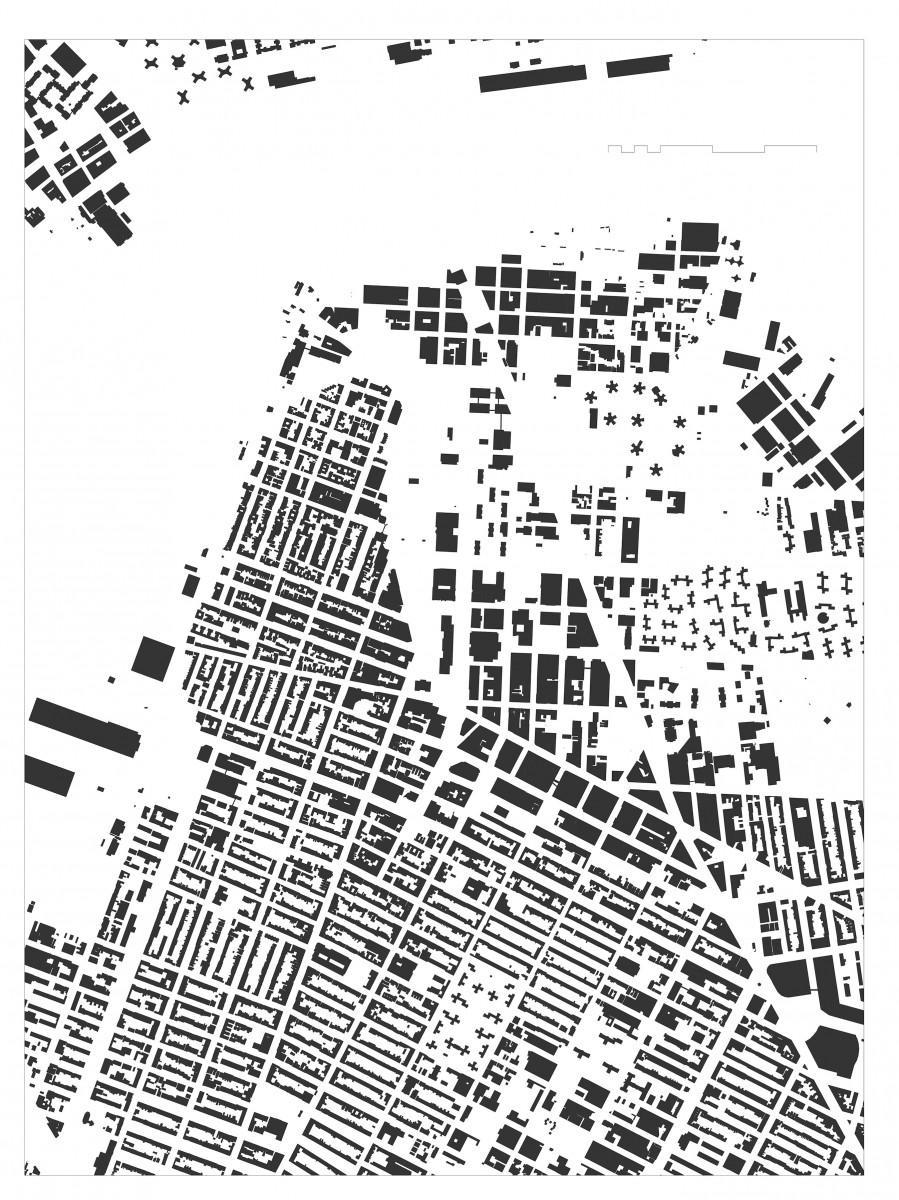

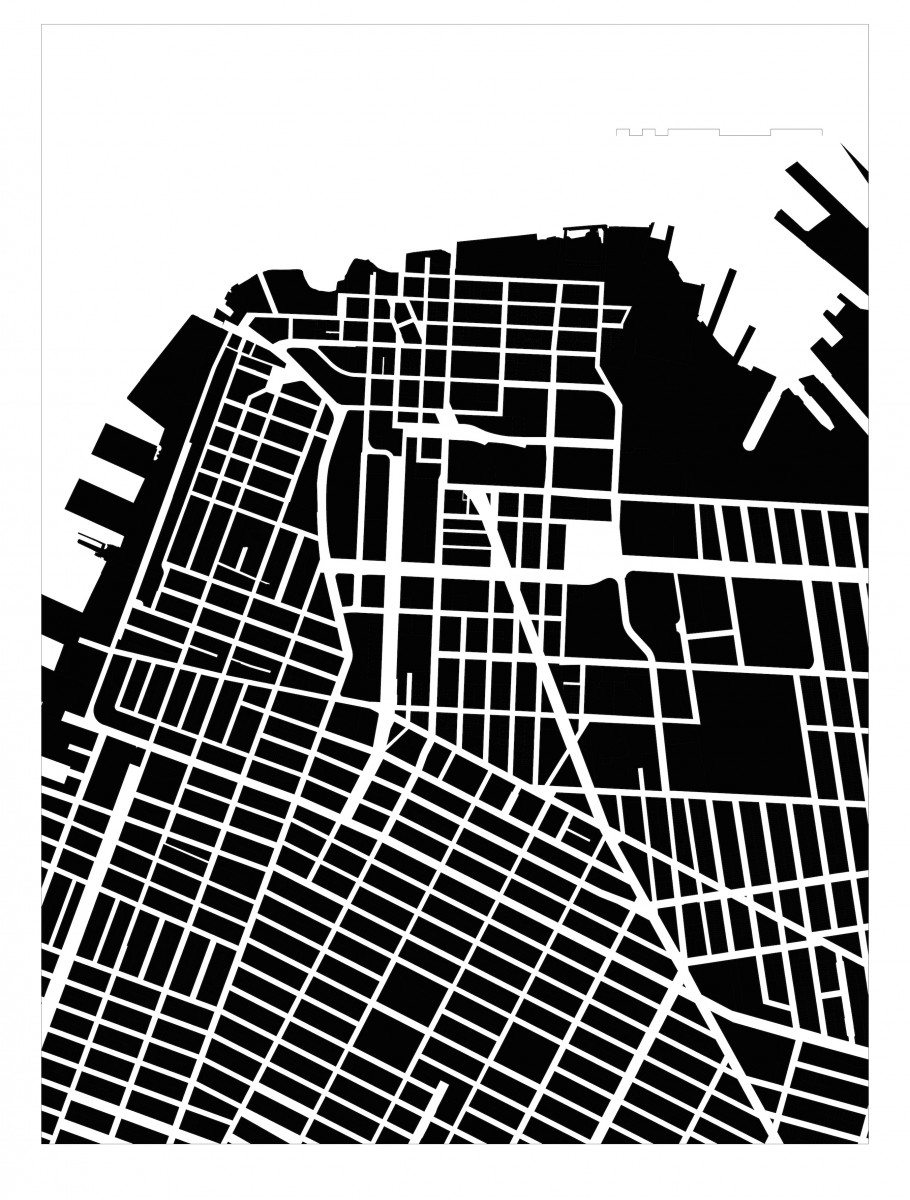

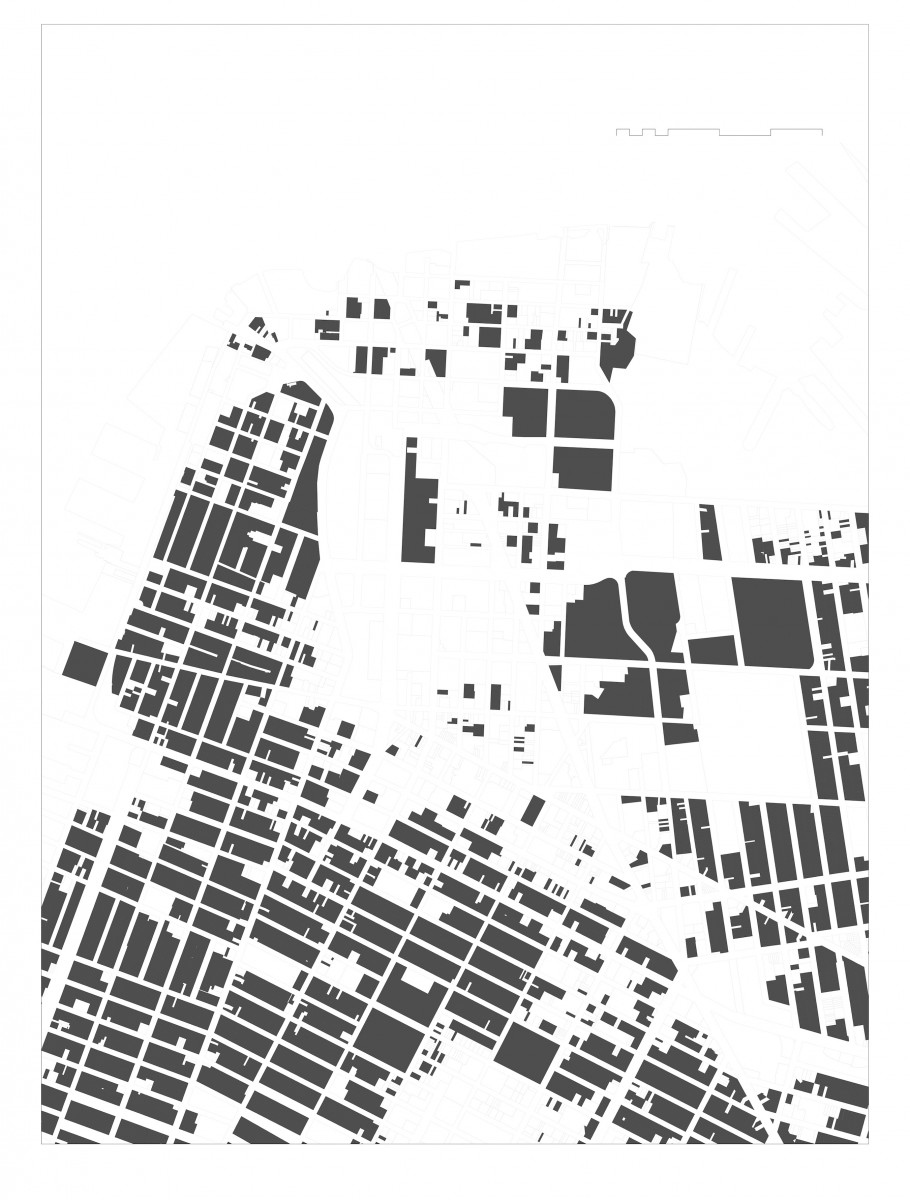

URBAN PATTERN: Figure ground diagrams clearly illustrate the disruption to the urban structure in this precinct. Analysis of both block structure and building footprints show a normative pattern of streets and blocks in the neighborhoods to the south and west. The core of downtown Brooklyn has a different scale of buildings as well as a less regular block structure. The area between Tillary Street and Dumbo -Navy Yard is marked by large open unbuilt spaces. Building mass is the first critical element that defines streets and gives them their character. This is the reasoning behind many sections of the zoning text where the text requires or encourages building mass at the property line. Brooklyn Heights reflects this strategy clearly. An overabundance of ill-defined open space in an urban area can result in blight, especially when the open space is under used and not well maintained.

BLOCK SIZES: The block patterns of this section of Brooklyn are unusually irregular. The predominant block orientation to the south of downtown Brooklyn is with the long dimension in the east to west alignment. Brooklyn heights and Dumbo have an intriguing variety of block patterns and sizes. Typical blocks in the surrounding neighborhoods are 200’-300’ x 500’. Larger scale blocks permeate the downtown area, with a number of blocks oriented north-south with lengths exceeding 1000’.

URBAN BARRIERS: The major roadways through the precinct are wide with significant traffic. For long stretches jersey barriers block any crossings, allowing traffic to move at higher speeds than typical city streets. Where crossing is possible, these streets are intimidating and dangerous for the pedestrian. Large scale blocks by definition limit the urban flow of pedestrian, bike, and vehicular traffic and concentrate it on fewer streets. Parks and green open space are almost always a positive asset in an urban environment. If the parks are under used, however, they can contribute to a dead zone where activity is curtailed. In these cases, the larger the scale of the park, the larger the zone of low activity and vibrancy. This is the case for the open space stretching from Borough Hall to the Brooklyn Bridge. The lack of activity in the Korean War Memorial and the Brooklyn War Memorial results in the parks acting more as barriers between neighborhoods than centers of activity drawing from all surrounding neighborhoods. The compounded impact of the disrupted urban structure, the wide and forbidding traffic thoroughfares, and the over scaled north-south blocks is a series of barriers that divide the precinct and isolate the areas flanking Jay Street.

POPULATION DENSITY: Residential population in Downtown Brooklyn exhibits a common phenomenon: gaps of residential units surrounding the business/civic center. With low residential density in the Downtown area comes less activity, especially outside of business hours. Services in these areas are also limited without a population to serve, including grocery stores and cafes. Spikes in residential density are due to large scale tower estates including public housing as well as some cooperatives.

ZONES OF JAY STREET: Zooming in on Jay Street, the students made a key summary observation: Jay Street is divided into three distinct zones with Tillary and the Manhattan Bridge as the thresholds between the zones. The northern zone has the distinctive character of Dumbo, with a combination of new residential towers and 19th century warehouses and loft buildings. The central zone is much less active, with multiple parking lots, a super block on the west side blocking all circulation to the west for over 1000’. The southern zone spans from Fulton Street Mall to Tillary Street. This zone will be fully built out with the completion of the new Citytech academic building. This zone is the most active. Each zone is approximately 1/4 mile long north to south (5 minutes walking distance.) But the perceptual distance is much greater with the major thresholds breaking the sense of continuity of the street.

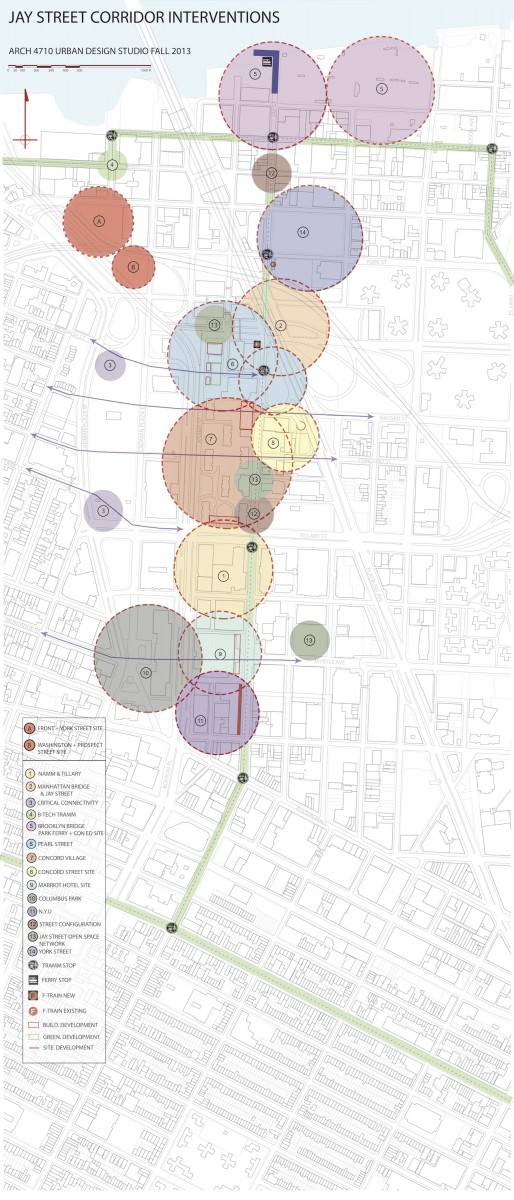

INTERVENTIONS: