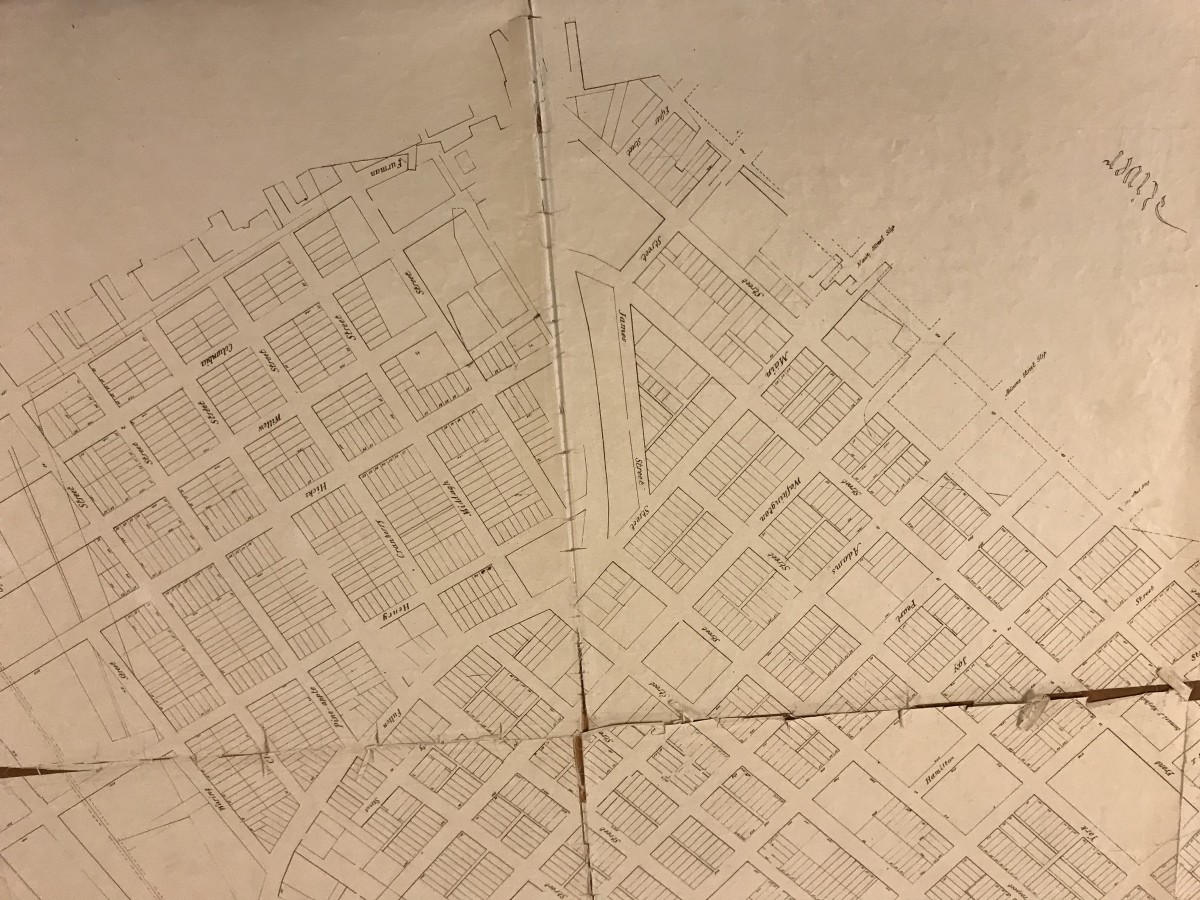

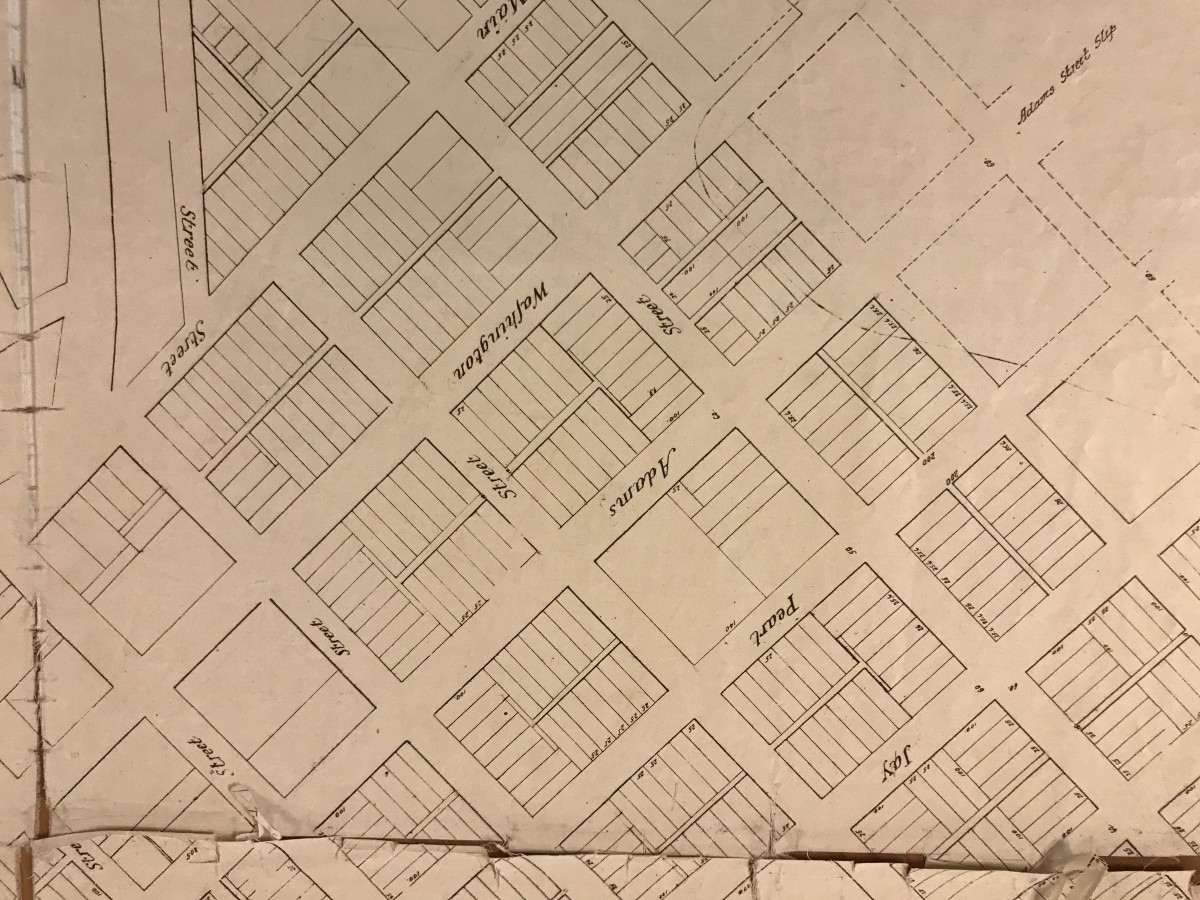

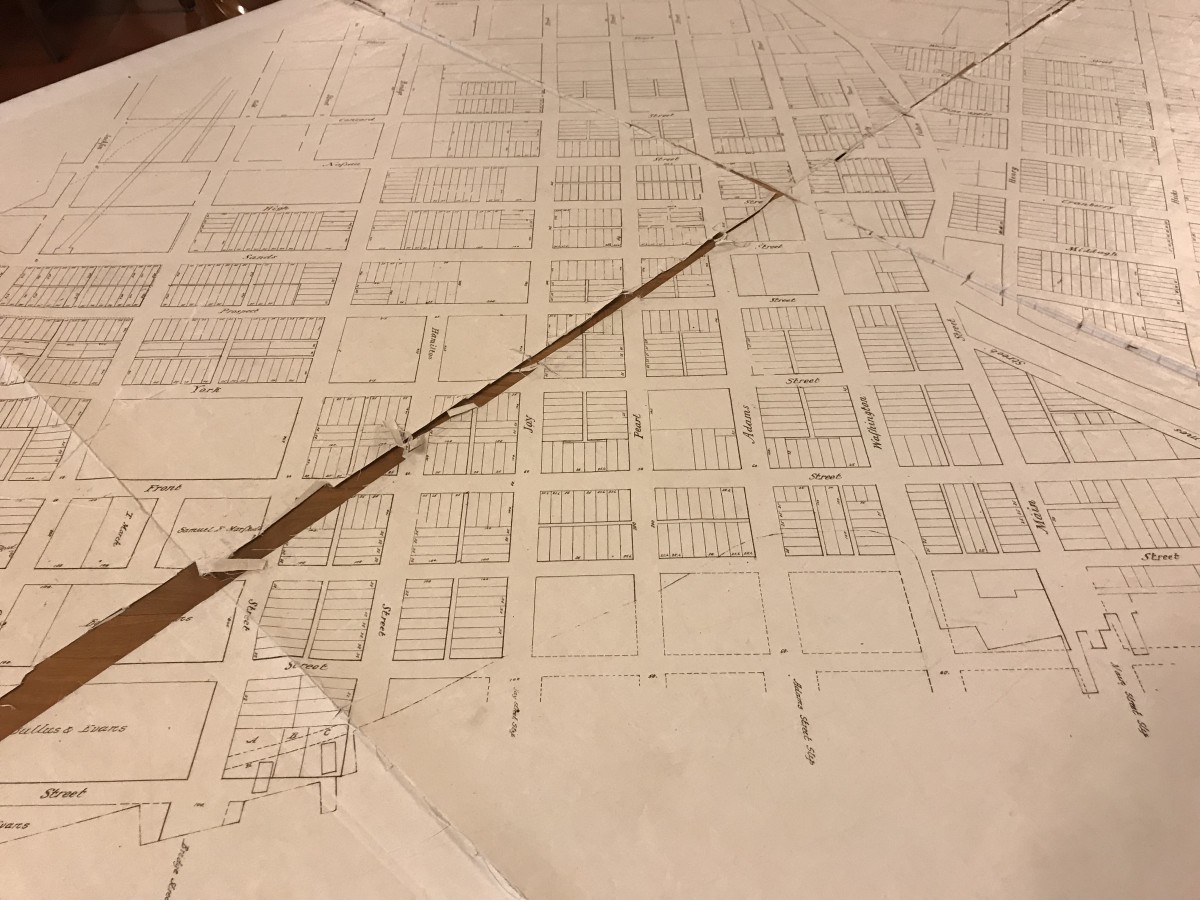

A survey of early Brooklyn in 1819 reveals a subtle differentiation of the block structure in the burgeoning city, perhaps evidence of rival concepts for the character and design of each development zone. Fulton Street, the historic roadway that links the ferry landing to the heart of Kings County and Long Island beyond, is the natural urban (not quite geographic) center of the land area between the bluffs overlooking the harbor and Wallabout Bay. The land on either side of Fulton was controlled by different families. Joshua and Comfort Sands held a large parcel to the west of Fulton, while other families including the Hick’s and the Pierrepont’s controlled the east. The blocks to the east of Fulton show the standard application of 25′ wide plots to blocks in a simple pattern of nominally oriented north and south lots. Special treatment is given to important streets, in this case Henry and Hicks, with the lots rotated to front onto these streets. The lots back up to each other, with the entire area of the block subdivided into private land.

Across Fulton Street a different pattern is apparent. Between Fulton and Wallabout Bay, a majority of the blocks that are shown subdivided utilize small scale lanes and/or alleys as a secondary and tertiary urban structure of public access. This unusual urban structure for Brooklyn and New York facilitates practical servicing of the lots from the rear, a structure planned or adopted in other American cities, including Philadelphia and Savannah. The system of lanes and alleys also facilitates another unusual feature, mid block lots that are typically slightly wider and longer that run perpendicular to the rest of the block’s lots. These particular blocks stand out in the survey as if they were intended to give a special quality to the neighborhood. To be sure, the application of alleys and lanes would add a texture to the streetscape that the other side of Fulton street did not possess.

The historical record notes that the Sands brothers desired to brand their parcel as a new town called “Olympia”. Perhaps this urban structure was an intentional means of differentiating their development. It could also be motivated by the anticipation of commercial and industrial activity along the waterfront, providing the servicing of blocks in a more discrete manner.

This unique structure was wiped out as Brooklyn developed, most significantly with industrialization of the waterfront area that demanded larger lots, and finished off by the urban renewal projects of the mid 20th century. Harrison Alley in Vinegar Hill near the boarder of the Navy Yard is likely the only remnant of this intriguing urban vision.

Leave a Reply