Politics and Journalists’ Language

Why does journalism continue to fail so completely in its coverage of the outrages of Trump and the new age of American politics? Why does its language continue to provide cover for radical change, making it seem as if it’s simply business as usual?

Why don’t reporters change the words they use when describing a changed situation?

NYU professor of journalism Jay Rosen compiled a Twitter thread into a Facebook post on the last day of April 2017. He titled it “The Everyday Language of News Distorts the Reality of Trump.” As I was reading it, I kept thinking about George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language.”

Rosen writes, “Forced to choose between inventing a language for a presidency without precedent and distorting the picture by relying on normal terms, the newswriters have frequently chosen inaccuracy by means of a received language.” Orwell wrote, “Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration.” These two thoughts are connected absolutely. The latter precludes the former, absolutely.

But the latter is rare—even though Orwell so long ago provided a plan for escaping the quicksand that the Age of Trump represents for political journalists. All they have to find is the will to follow it.

Saving themselves from the swamp of murky thinking that Trump thrives on only requires returning to language basics, something any journalist should be quite willing and able to do. It only requires paying close attention to Orwell’s six rules for “cutting out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally.” These are basic rules of writing, though often forgotten:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Rosen’s complaints about political reporting would be addressed if every Washington correspondent kept these rules taped above their screens and referred to them each time they wrote a sentence. Using an empty phrase, PBS Newshour speaks of Trump’s “foreign policy accomplishments” when Trump doesn’t have a foreign policy—something the correspondent would have realized if she or he had examined the phrase before using it. As Rosen puts it, you can’t call it “policy” when “stuff happened, and he [Trump] reacted.” That might even be effective, but it is not “policy.”

In the new political world, “foreign policy,” as once conceived, has no meaning. It is used because the phrase has always been used. It is much like the “dead metaphors” Orwell complained of; it is trotted out in place of considered examination of actions and the choices of the language that best describe them.

Rosen claims, “the press is running into trouble with basic description because the thing being described violates baseline expectations.” When that is the case, it is necessary to go back and look at those expectations, and at the language that carries them. This has not been done by members of the Washington press corps, not during the Trump administration. The reporters, as Rosen notes, rely on what were once the normal terms of political journalism. They do this because jettisoning them can make the reporters sound extreme, as though they have gotten rid of the normal, themselves.

Rosen writes, “When extreme facts about a president cannot be rendered in news space without the speaker sounding extreme, the facts had better watch out.” Reporting on bizarre and unusual situations cannot be done accurately without the use of language that reflects their oddity. Reliance on worn-out and, given the current climate, inappropriate images reduces the accuracy of the reporting, even if it doesn’t endanger the journalist who has evaded stepping out of the bounds of the usual.

When Trump ‘rolled out’ his tax plan in late April, it consisted of what Rosen describes as “a page of bullet points”—not a “plan” at all in the sense of what we once expected from governmental entities—or of anything showing “evidence of planning or deliberation,” as Rosen points out. Certainly not of the sort one, until recently, expected from a “plan.”

As Orwell wrote, “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” He goes on:

The debased language that I have been discussing is in some ways very convenient. Phrases like a not unjustifiable assumption, leaves much to be desired, would serve no good purpose, a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind, are a continuous temptation, a packet of aspirins always at one’s elbow…. By this morning’s post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he ‘felt impelled’ to write it. I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence I see: ‘[The Allies] have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany’s social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a co-operative and unified Europe.’ You see, he ‘feels impelled’ to write—feels, presumably, that he has something new to say—and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern. This invasion of one’s mind by ready-made phrases (lay the foundations, achieve a radical transformation) can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.

Such was the state of journalism in 1946—and such is its state seventy-one years later. We may, like the author Orwell describes, ‘feel impelled to write,’ but we rarely even stop to examine what that means. And that is just what journalists today must start doing. They have to stop using stale phrases like “steep learning curve,” one of the ones Rosen points out, in relation to Trump. Is there proof that he is actually learning? “Reacting, yes… but learning?” asks Rosen.

Orwell said he had been considering “language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought.” Political language has never been strong on clear expression. Journalists’ language, in response, should be making that its focus—especially when its topics have been wrenched from their former normality.

Though he addressed an earlier time, Orwell’s last words in “Politics and the English Language” need to be taken to heart by all who write on politics in the Trump era. He writes that:

one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself. Political language—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one’s own habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase—some jackboot, Achilles’ heel, hotbed, melting pot, acid test, veritable inferno, or other lump of verbal refuse—into the dustbin where it belongs.

We can come up with our own list of phrases today—and Rosen has provided a start. Come up with it we must, or we risk turning our language against ourselves—as much as it is already turned against us. The culprits are people who make radical changes, aware that they can get away with them under the cloak of the words of the normal of the past, protected by the lazy use of language itself.

Who Can Save Journalism?

What’s happening to our discourse?

What’s happening to our discourse?

Have we abandoned all common assumptions simply for the sake of opposition?

The ‘he said, she said’ that has been at the center of much journalism for the past half-century (with the journalists as putative ‘objective’ reporters outside of that dynamic) has been turned against the Fourth Estate by a carnival barker. This is an effective tactic as practiced by Donald Trump and his minions, for it effectively boxes in the press, making anything reporters write that does not conform to administration viewpoints into something oppositional. The ‘he said, she said’ shifts, becoming a ping-pong game between press and president where once the press thought of itself simply as scorekeepers.

No longer can the press claim simply to report; now, it has to defend itself as well, returning volley for volley.

Seeing this, some on the right can hardly contain their glee. Columnist for The New York Times Ross Douthat, for the purposes of a recent op-ed, styles himself a journalist (though I don’t believe he has much experience with the shoe-leather reporting at the heart of the profession). He places the blame for the new paradigm on the press itself:

Mainstream journalism in this strange era may be freer than the fearful anticipate, but not actually better as the optimists expect. Instead, the press may be tempted toward — and richly rewarded for — a kind of hysterical oppositionalism, a mirroring of Trump’s own tabloid style and disregard for truth.

Douthat goes on to say that the “danger for the established press, then, is the same danger facing other institutions in our republic: that while believing themselves to be nobly resisting Trump, they end up imitating him,” not understanding (or claiming not to) that Trump has forced the press into this situation. They are doing “a demagogue’s work for him.” His cynicism about the profession comes through in his final, smug plea, “Fellow journalists, don’t do it.”

To not ‘do it,’ however, requires a complete revamping of the profession—something Trump is counting on not happening. Something that Douthat, also, knows is unlikely.

For the last quarter of a century, one of the only voices continually advocating for a change in the practice of journalism—and showing ways of doing it—has been New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen. His tenure as a working journalist (like mine and like Douthat’s), however, was not particularly long, opening him up to accusations of being an outsider who really doesn’t understand the travails of the front-line reporter. Such a charge was levelled against him again today, this time by New York Times reporter Glenn Thrust.

Rosen recounted their exchange on Facebook:

Earlier today Glenn Thrush of the New York Times told his colleague Maggie Harberman that he has known [White House Press Secretary] Sean Spicer for years and he is a total pro. So I just said to him on Twitter: hey Glenn, I thought you said this guy was the consummate pro, followed by the link I just shared with you [about his rant at the press about attendance at the inauguration].

His reply: “Jay… come down here and do it yourself… How many deferments have u applied for in this war?”

Ignoring the intended insult, Thrush’s retort makes me think that the likelihood of real change in journalism—for the better, at least—is not likely to happen, not even in the face of the concerted attacks of Trump and his minions. Not unless attitudes change dramatically.

The sense of being in the trenches, of hunkering down for a fight does the profession no good, no more than feeling that only those who have ‘been there’ can understand what they are going through. Outsiders like Rosen, like Douthat and like me haven’t a clue what they go through–or so they think. Unfortunately, this pull-up-the-drawbridge mentality leaves the profession no place to turn to, when what it needs is exactly that, outsiders around new corners with ideas of new ways to collect and report the news.

The situation today certainly demands a new type of journalist, not simply a continuation of the old with a set idea of what the profession should and can be. Rosen has been advocating for new types of journalism since before he and “Buzz” Merritt tried to institute ideas of “public journalism” at the Wichita Eagle more than 20 years ago (I wrote about this in a chapter, “The Movement Toward Public Journalism” in The Rise of the Blogosphere). He cares more about change for the better more than he does about protecting those in the profession.

As I’ve been writing this, Rosen has posted “Send the Interns,” a piece expanding on something he suggested a couple of months ago, that the most junior journalists, not the most experienced, be sent to cover the White House. Not really tongue-in-cheek with his advice, Rosen exhorts the news media to refuse to cooperate with their own delegitimization at the hands of entertainers and manipulators:

They don’t have to lend talent or prestige to it. They don’t have to be props. They need not televise the spectacle live (CNN didn’t carry Spencer’s rant) and they don’t have to send their top people to it.

They can “switch” systems: from inside-out, where access to the White House starts the story engines, to outside-in, where the action begins on the rim, in the agencies, around the committees, with the people who are supposed to obey Trump but have doubts.

This, as Rosen and any student of journalism knows, is an expansion of the methodology of I. F. Stone, who buried himself in government documents and the expertise of unheralded bureaucrats rather than running for the spotlight as so many modern journalists do. It takes work, though, and time—not something that many journalists, who themselves love the limelight and the chance to hobnob with the rich and famous, are willing to commit to (certainly not in anonymity).

For this coming semester, I am already restructuring my journalism course to reflect the changes ‘fake news’ is forcing on the profession—but I think I am going to have to do much more. My students, after all, are the interns (or intern wannabes). Instead of simply sending them in, what I need to do is illustrate the problems and ask them, as young outsiders with an interest in the profession, what they can come up with as possible solutions. I’m going to try to give them the respect that I, as a student in the sixties, demanded of my own elders.

Maybe I can learn something. Maybe we all can. We can’t simply continue down the same old path.

Undoing the Fakery: Real Journalism and Writing in the 21st Century

How wrong mere logic can be when it becomes detached from reality. –Edward Upward, 1988.

With fakes everywhere—including fake news sites, fake news stories, faked incidents and even fake journalists—teaching journalism or any other kind of writing also becomes teaching discernment and discretion. It becomes teaching how to be honest in writing and research, and why.

Yet, in a milieu of dishonesty, it’s increasingly hard to convince students that they need to be forthright in their explorations and presentations. It’s hard to convince them not to retreat behind assumed belief, the ideas they carry into the classroom, as personal “truth” (whatever that is). Everyone is lying, after all; why should their teachers be any different?

Everyone has an agenda, people believe—including students; we’re all attempting to convince, not inform—and we’ll twist the “truth” to meet our goals.

Well, yes. But it’s not so simple, not so easy to justify blocking things out. Certainly, misinformation abounds. But both journalists and students are tasked with sifting truth from chaff. If they don’t, they fail. Journalism fails. Education fails.

Writing about deliberate verbal misdirection almost a century ago, I. A. Richards and Charles Ogden, quoted Benjamin Jowett’s then-recent translation of Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War. Given its relevance to my concerns about teaching, about meaning and truth in the public sphere (the very ones that led me back to Richards and Ogden), I thought to look at a couple of other translations, one older, one newer. Here they are, in order of composition:

The received value of names imposed for signification of things was changed into arbitrary. For inconsiderate boldness was counted true-hearted manliness; provident deliberation, a handsome fear; modesty, the cloak of cowardice; to be wise in everything, to be lazy in everything. –Thomas Hobbes, 1629.

The meaning of words had no longer the same relation to things, but was changed by them as they thought proper. Reckless daring was held to be loyal courage; prudent delay was the excuse of a coward; moderation was the disguise of unmanly weakness; to know everything was to do nothing. –Benjamin Jowett, 1900.

They reversed the usual evaluative force of words to suit their own assessment of actions. Thus reckless daring was considered bravery for the cause; far-sighted caution was simply a plausible face of cowardice; restrain was a cover for lack of courage; an intelligent view of the general whole was inertia in all specifics. –Martin Hammond, 2009.

All three have similarity enough to give a good idea (to someone like me, who doesn’t read Greek) of the intent of the original passage. At the same time, they show how the English language changes—and how small differences in meaning can lead to large differences in assumption. Take just the last phrase in each: “to be wise in everything, to be lazy in everything,” “to know everything was to do nothing,” and “an intelligent view of the general whole was inertia in all specifics.” They are the same—but different.

Sure, the differences have to do with time of composition, changing styles of translation and individual artistry, but the meanings are different, too—even while similar. Not only that, but each could be used in different senses and even opposing purposes in today’s American political environment. At the same time, each and the rest of the list (Thucydides’ point) is both meaningless and an abuse of language (or meaning). Orwellian before Orwell.

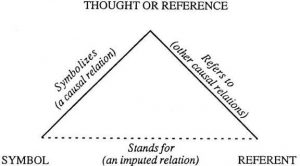

What led me to Ogden and Richards’ discussion is our current inability to get beyond belief to truth through language—in our political discussions and in our classrooms. I wanted to move backwards from contemporary discussions of the uses of language to their predecessors, perhaps finding a simpler way of getting students over the barrier between what they believe is true and what is true to the world—and how to write about it adequately. In The Meaning of Meaning, Ogden and Richards present a triangle I thought might be useful, of symbol (word), thought (idea) and referent (world) from an Aristotelian base. It looks like this:

Simplistic though this may be, it possibly can help me cut through the wall of belief that so effectively stops discussion in the classroom as in the nation. How does one respond when, say, Donald Trump, for example, tweets that he “won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” News media added “falsely” or “with no evidence” to their headlines, but not even that solves the problem posed by the very fact of the tweet: Trump is taken at his word by millions.

By going back to Odgen and Richards, I am deliberately sidestepping, avoiding (among many others) Peirce, Wittgenstein, Ayer, and even Rorty. Mine is not a philosophical investigation but a quest find a way to break down a barrier we have raised in public and educational discourse. I’m looking for simple and utilitarian answers, not contingencies nor verifications, for something that can be used to break the logjam in politics and in the composition classroom created by unswerving belief and brazen lies. I am no philosopher or linguist, anyhow. I am merely a writing teacher and a student of American culture with a particular concern for contemporary political discourse.

In the context of the triangle, Trump’s tweet counts as an idea expressed in words but without referent. Without referent, it should collapse into a line, two dimensional and without relevance except for the nature of its source. That is, if it weren’t Trump’s tweet, it would be dismissed completely. This, not surprisingly, is the same problem that composition teachers often have with their students. That something is a student’s idea makes it important, not the referent (or the world), or the symbol (or the words). Like Trump, they don’t need to explain, students often think, merely to aver. To them, the personal source makes it significant and viable on the face of it—that is, the nature of the source changes the nature of the statement. Yet that source is not even part of the triangle (this becomes significant to understanding the New Critics, followers of Richards, who would dismiss intentionality—more about that in a second). That is, Trump’s intent (or his personality) has nothing to do with the validity of his statement—not, at least, in terms of the triangle.

The quandary for news media, all of which know that the statement in Trump’s tweet is nonsense, was how to handle something that makes no sense in terms of this traditional triangle. As a result, the tweet was presented with various degrees of hamfistedness or deftness, some platforms, on recognition of the problem, quickly amending their headlines and stories to more clearly reflect the speciousness of Trump’s assertion.

In a classroom, there would be a similar range of responses with, however, even more of an attempt to ‘respect’ the speaker—and therein, once again, lies the problem: We add that speaker into a triangle that has no place for her or him, not on a flat diagram. You can’t make that triangle into a pyramid without creating a third dimension, though many of us try.

Let’s back up a bit and add in the New Critics. Knowing you can’t add the intent of the speaker into the triangle, the New Critics decided to go the other direction, banning intent instead. Some years ago, in an article on New Critical anti-intentionalism, I wrote:

The anti-intentionalists distinguish between verbal behavior meant to make a point and verbal behavior meant to show someone making that point, placing verbal art in the second category and claiming it is thereby removed from intentionalism and stimulus/response continuity. There is certainly a difference between someone yelling “fire” from the audience of a theater and an actor on stage yelling out the same word.

This difference can cause problems in journalism and in the classroom. Is an event (verbal or otherwise) truth or play? And how does one differentiate? Jay Rosen, who teaches journalism at NYU explains the impact these questions on journalism by pointing out the difference between “evidence-based” and “accusation-driven” reporting. His evidence-based reporting deals with truth of the yell in terms of the actuality of the theater and not the play on the stage. Accusation-driven reporting sidesteps the difference between the two, sometimes giving both equal weight under a cloak of ‘objectivity.’ The truth of something doesn’t matter, only that claims are made does. Rosen writes, “If you are evidence-based you lead with the lack of evidence for explosive or insidious charges. That becomes the news. If you are accusation-driven, the news is that certain people are making charges.” He goes on, “Instead of defining public service as the battle against evidence-free claims, they will settle for presenting the charge, presenting the defense, and leaving it there, justifying this timid and outworn practice with a ‘both sides’ logic that has nothing to do with truthtelling.” The former demands examination of intent, making that (and not the accusation) the story, erasing the possibility of falling back on that ‘both sides’ equivocation. The latter simply reports the charge.

The problem is, Trump’s tweet cannot be examined as a stand-alone text unless one is willing to posit that it creates its own reality. If it does, then a story about it and competing ‘realities’ is completely justified—and the triangle disappears. Truth disappears.

Without evaluating the speaker (or writer) and his or her intention, we retreat into a world based on the assumptions behind the words–and those may have nothing to do with the triangle that most reporters try to hug. This may be fine in the study of literature, which was the New Critics’ bailiwick anyhow, but it does not work in journalism, where the reason behind expression of the words, their purpose, is as important as the words themselves.

Just so, when we write, we need to consider two factors, the triangle itself and the reasoning behind our own attempt at expression. Can we remove our own beliefs from our explorations, examining our words and the world, our ideas and the world, and our words and their relationship to our ideas? Can we do this without retreating to ‘It’s what I believe, so there’? Can we separate belief, which relies on assumption, from ideas, which rely on world and words?

It’s easiest, when writing, to imagine that one is simply reporting the words and actions of others, but that is never sufficient. Not only does that make the reporter eminently manipulable (just look at how easily Trump out-played the antagonistic news media), but it leaves the news–or the paper–incomplete. If one does not step outside of the simple triangle and examine motivation, one will never have a story that can stand on its own. It’s flat and will fall down. Intent provides a third leg, expanding the story to a pyramid, something that can stand for centuries.