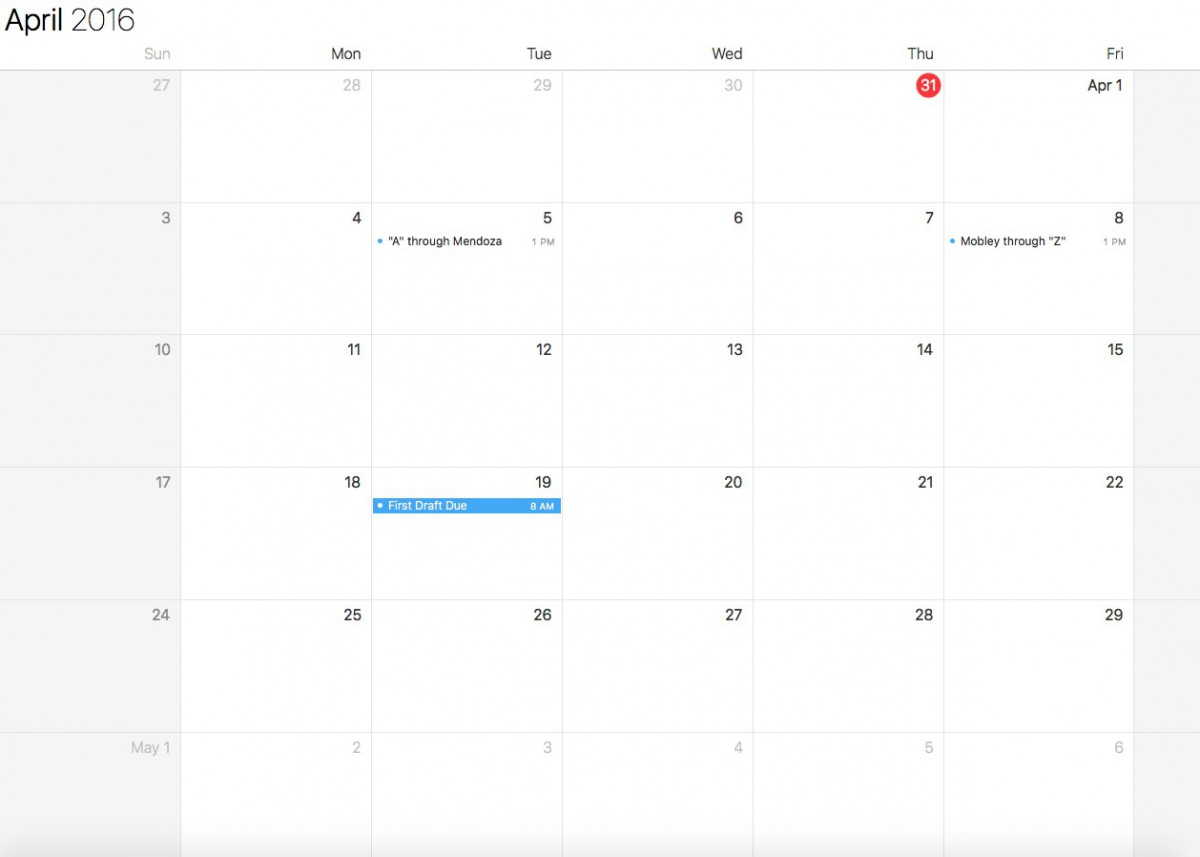

A number of you may be asked to not only do a regular bibliography, but also to annotate your bibliography. If you are asked to do this, it is due May 10. (The Professor will read your First Draft papers first, and then reach out to you via email or in person to tell you if you must complete one.)

Here is information Online, published by Cornell University. You may find it helpful. You can also visit the link directly here:

WHAT IS AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY?

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

ANNOTATIONS VS. ABSTRACTS

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they expose the author’s point of view, clarity and appropriateness of expression, and authority.

THE PROCESS

Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research.

First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

CRITICALLY APPRAISING THE BOOK, ARTICLE, OR DOCUMENT

For guidance in critically appraising and analyzing the sources for your bibliography, see How to Critically Analyze Information Sources. For information on the author’s background and views, ask at the reference desk for help finding appropriate biographical reference materials and book review sources.

CHOOSING THE CORRECT FORMAT FOR THE CITATIONS

Check with your instructor to find out which style is preferred for your class. Online citation guides for both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) styles are linked from the Library’s Citation Management page.

SAMPLE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENTRY FOR A JOURNAL ARTICLE

The following example uses the APA format for the journal citation.

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554.

The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

This example uses the MLA format for the journal citation. NOTE: Standard MLA practice requires double spacing within citations.

Waite, Linda J., Frances Kobrin Goldscheider, and Christina Witsberger. “Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults.” American Sociological Review 51.4 (1986): 541-554. Print.

The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.