Evelyn Richardson

Professor Jason W. Ellis

ENG2420

20 May 2020

The Science Fictional Designs of Superstudio

Superstudio, an architectural firm that started in the late 1960’s and was a product of a generation that came out of World War II, questioned the ideas of mass consumerism and the cultural unification of our world. The science fictional designs of Superstudio could be considered a form of science fiction because their expression through visual mediums dig out prophetic information regarding cultural issues of their time. As Joanna Russ (1937-2011), a well-known female science fiction writer states regarding the identity of science fiction literature, “It draws its beliefs, its material, it’s very attitudes from a culture that could not exist before the industrial revolution, before science became both an autonomous activity and a way of looking at the world” (Russ 25). Collages and urban fanciful renderings were the main visual language they used to express their questions on a utopic and a dystopic society’s environment. Examining Superstudio’s work and the subjects they address parallel to many common themes that can be found in science fiction literature.

Superstudio’s work emerged from the same influential sources that science fiction literature stems from, the first being “The Age of Enlightenment.” Superstudio’s project, “Reflected Architecture”, was influenced largely from a term that came about during the French Enlightenment period, “speaking architecture” or “Architecture parlante”. The terms meaning is, “architecture that gives an idea about its purpose through its form or appearance. Refers to a building that in some way obviously or overtly states its purpose” (Przybylek). This term was first used by French architect and visionary Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806), who imagined among many other things, “a tube with water running through it to be used for the director of a waterworks” (Przybylek). Superstudio adapted this technique graphically, a literal illustration of their ideas and concepts. Their “Reflected Architecture” correlates to a conceptualized city they published in “Twelve Cautionary Tales for Christmas: Premonitions of the Mystical Rebirth of Urbanism.” Their fifth city described by Superstudio wrote:

The city is a dazzling sheet of crystal amidst woods and green hills. On nearing it, one realizes that it is made up of the covers of 10,044,900 crystalline sarcophagi, 185 cm long, 61 cm wide and 61 cm deep… Inside each sarcophagus lies an immobile individual, eyes closed, breathing conditioned air and fed by a bloodstream — in fact, the blood system is connected to a purifying and regenerative apparatus which, through toxin elimination and doses of hormones, prevents ageing (Frassinelli).

Using visual mediums and writings, they were able to create a “speaking architecture” that reflected their conceptualized ideals of a futuristic world and how society would connect and communicate with one another.

If it had not been for the periods in history such as, the Scientific Revolution or the Industrial Revolution, Superstudio would not have had the concepts that fed and influenced their futuristic notions on culture and society. It could be argued Superstudios work is a form of speculative fiction matching with Robert Scholes (1929-2016) definition of what science fiction is, he wrote:

The tradition of speculative fiction is modified by an awareness of the universe as system of systems, a structure of structures, and the insights of the past century of science are accepted as fictional points of departure. It is a fictional exploration of human situations made perceptible by the implications of recent science. Its favorite themes involve the impact of developments or revelations derived from the human or physical sciences upon the people who must live with those revelations or developments (Scholes 214).

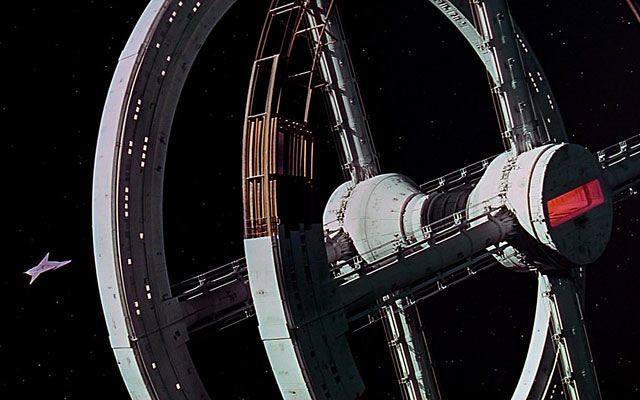

Superstudio was greatly influenced by scientific events of their day, which is illustrated in their collection called “Interplanetary Architecture.” Alessandro Poli one of Superstudio’s members created this collection based on his fascination of space exploration and the major historical event, the landing on the moon. In this collection he illustrates a highway from earth to the moon. This project was also a spinoff of their earlier project from the “Twelve Ideal Cities” correlating to their fourth city called Spaceship City, where Superstudio describes this project as, “A ring of sleeping inhabitants moving towards a planet thousands of light years away where descendants of the sleeping crew will wake and found a new land.” (Superstudio p.8) This project reflects similar concepts derived from the famous science fiction film “2001 Space Odyssey” directed by Stanley Kubrick (1929-1999) released in 1969. This film, though it may not be the main them of the plot, explores this theory of space travel being a common accessible option in the future. The landing on the moon in the 1960’s had such a huge impact on the culture of that day. It is logical that Superstudio also would correlate this subject with an architectural program posed for a design in space and theorize humanity may inhabit that frontier one day.

Romanticism is another key ingredient that can be found in science fiction literature as well as in Superstudio’s work. They produced several manifestos that correlate to their renderings and collages, which illustrate their concepts of social change and revolutionary ideas of consumerism and mass production. In a Superarchitecture exhibit that was held in the Italian city Pistoria in December 1966, Superstudio wrote the following polemic manifesto, “Superarchitecture is the architecture of superproduction of superinduction to superconsuption of the supermarket, of the superman, of the super gasoline” (Quesada 23). These concepts differ from the Pop Art culture that was a major dominate scene in the 1960’s. This manifesto claims, “that the figurative or formal data of images have a revolutionary potential. Hidden behind an intention to demythologize, the Pop myth of the image as an almighty tool” (Quesada 23). Superstudio believed that an image is meant to trigger and inspire a person to think, to gain a line of conscientiousness, which in turn gives the power back to the individual. In a way you could see this argument Superstudio poses in their exhibition as a form of Conte Pilosphque. They tried to debunk Pop Cultures influence and concept of being the end all main attraction and not continuing the thought any further than what it presents. This idea that Superstudio argues, bringing the power of thought to the individual, correlates to the romantic notions of individuality in romantic literature. These ideas also coincide with Hugo Gernsback’s (1884-1967) notion that science fiction literature is a combination of an idea that is meant to inspire, “charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision” (Gernsback 3). These elements all can be found within Superstudio’s works.

Further connecting to these romantic notions of individuality can be seen in their series of films they developed called “Five Fundamental Acts.” This compilation touched on five major themes they felt were what being human was, which are, life, education, ceremony, love, and death. In two series “Life” and “Ceremony” they further developed this argument to give the power back to the individual through the absence of objects or architecture. They developed this idea called the “invisible house.” They felt taking away the emphasis of inanimate objects and a physical form to inhabit space gave man certain freedoms of choice. Superstudio felt it could bring mankind back to an authentic way of living, void of any emphasis to the object. This theory further emphasis what one science fiction scholar argues regarding the subject of what good science fiction is, Damien Broderick (1944) wrote:

SF is that species of storytelling native to a culture undergoing the epistemic changes implicated in the rise and supersession of technical-industrial modes of production, distribution, consumption and disposal. It is marked by metaphoric strategies and metonymic tactics, the foregrounding of icons and interpretative schemata from a collectively constituted generic ‘mega-text’ and characterization, and certain priorities more often found in scientific and postmodern texts than in literary models: specifically, attention to the object in preference to the subject (Broderick 155).

Superstudio was addressing these same issues Brodercik mentions, namely where he makes connection with “a culture undergoing the epistemic change” and the impact it has on “modes of production, distribution, consumption and disposal”. Superstudio was creating a visual narrative through their exhibition pieces as a medium theorizing on the impacts that these subjects had on the cultural scene of that day.

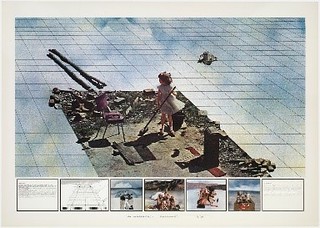

Further it can be argued that Superstudio is a form of “Gedankenexperiment” or a “thought experiment” which is also a characteristic of science fiction literature. In Superstudio’s own words regarding their goal they write, “We produced didactic projects, architectural critiques; we used architecture as self-criticism, endeavoring to inquire into its promotional mechanisms and its ways of working” (Superstudio 5). Visually this is illustrated in their collage entitled “Education” which again was part of the series of films they were trying to develop called “Five Fundamental Acts”.

Although the subject “Education” never ended up receiving funding to make the film, this collection illustrates visually an idea that humans have this unique ability to form intellectual connections and is a major characteristic that defines our species. Superstudio draws upon multiple layers making connections with this subject of “thought”, the work in itself illustrates a “mind experiment” that stands on its own just as that. John W. Campbell (1910-1971) also felt that a mind experiment could be made from multiple sources when he stated:

To be science fiction, an honest effort at prophetic extrapolation from the known must be made. Prophetic extrapolation can derive from a number of fields. Sociology, psychology, and parapsychology are today, not true sciences: therefore, instead of forecasting future results of applications of sociological science of today, we must forecast the development of a science of sociology (Campbell 91).

Campbell touches on this point that you can use different means and come from different schools of study to theorize upon certain outcomes.

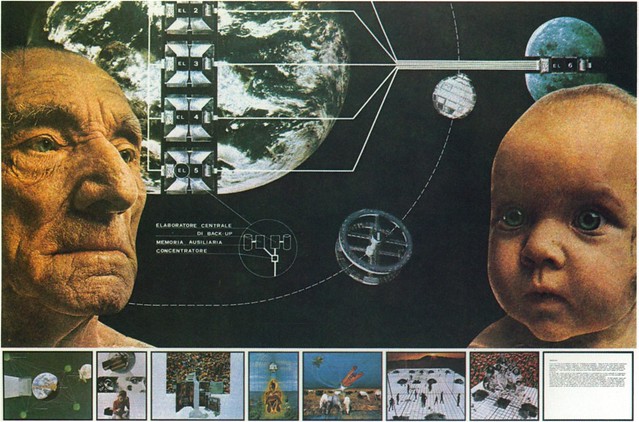

In a book entitled “Futuropolis”, written by a well-known science fiction writer Robert Sheckly (1928-2005), he uses this idea of having different schools of thought examine the subject of our built environment. In “Futuropolis” Sheckly compiled artist, writers, philosophers, architects and film makers visions and theories of futuristic cities. Within the book he features several pieces of Superstudio’s works. Sheckly believed most science fiction especially regarding future urban life was more about what would not work. He wrote “They are impressionistic rather then realistic. Its function is to suggest what you should avoid rather than what you should include” (Sheckly 7). Sheckly explores this topic, that science fictional designs are a didactic form of extrapolating what possibilities might or could be derived for our future, based upon a visual study many artist and architects have explored. Sheckly features Superstudio’s rendering “Continuous Monument” in the opening pages. Further on in the book Sheckly also takes portions of Superstudios project “The Twelve Ideal Cities.” From this collection he features the “2,000 Ton City” where individuals live within a cell whose brain is hooked up to an analyst which compares and collects desires. If an individual has rebellious thoughts against the utopic life society deemed to be a 2,000-ton force will crush them. Sheckly further expands on the issues these visual theorists are exploring which are the impacts politics and religion tyranny have had in their day. Superstudio was impressing upon their viewers the negative affects when a society allows an extreme utopic ideal to become a system we live by. A second city out of the twelve he features from Superstudio’s work is the “City of Order- where the inhabitants are programmed to fit the city, so that no one complains about the unpunctuality of the buses, or ever parks on a double yellow line” (Sheckly 55). This visual theory hints at a subject addressed in a short story written by Harlan Ellison (1934-2018), another well-known science fiction writer with his piece “” Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman.” Ellison also posed a dystopic society where all the citizens needed to fallow a timely system. He wrote an anthem in this piece where it states “And so it goes tick tock, one day we no longer let time serve us, we serve time and we are slaves of the schedule, worshippers of the sun’s passing, bound into a life predicated on restrictions because the system will not function if we don’t keep the schedule tight” (Ellison 150). Both Superstudio and Ellison pose the question in their works whether perfection is utopic, or could it be dystopic for our species.

In conclusion Superstudio’s work is still important and relevant for architects and designers today because they have addressed many important cultural issues that still connect with us. Society, though technology may have advanced or evolved, still questions the importance of popularized culture and its impacts on the art and the design community. We still are confronted with popularized opinions and questions of our built environment and the effects it has on us. There will always be periods of instability that will create radical movements that question what works and does not work for humanity regarding the environment we inhabit. As designers we are constantly confronted with questions on how society will interact in the future as did Superstudio with their “Connected Monument” project. Through Superstudios didactic illustrations and visual mediums we can extrapolate key lessons for moving forward with future thinking designs that will hopefully in better us.

Work Cited

Broderick, Damien. Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Campbell, Jr., John W. “The Science of Science Fiction Writing.” Of Worlds Beyond: The Science of Science-Fiction Writing. Ed. Lloyd Arthur Eshbach. Reading, PA: Fantasy Press, 1947. 89-101. Print.

Ellison, Harlan. “Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman. knape.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/9/3/12935004/ellison_repent-harlequin-1.pdf.

Gernsback, Hugo. “A New Sort of Magazine.” Amazing Stories April 1926: 3. Print.

Prina, Daniela. “Superstudio’s Dystopian Tales: Textual and Graphic Practice as Operational Method.” Writing Visual Culture n. 6. Special Issue: Text/Cities, Edited by Daniel Marques Sampaio, Michael Heilgemeir, www.academia.edu/13233018/Superstudio_s_Dystopian_Tales_Textual_and_Graphic_

Practice_as_Operational_Method.

Quesada, Fernando. “Superstudio 1966-1973: From the World Without Objects to the Universal Grid.” FOOTPRINT [Online], (2011): 23-34. Web. 20 May. 2020

Russ, Joanna. “Towards an Aesthetic of Science Fiction.” Science Fiction Studies 6.2 (July 1975). n.p. Web.

Scholes, Robert. “The Roots of Science Fiction.” Speculations on Speculation: Theories of Science Fiction. Eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2005. 205-218. Print.

Sheckley, Robert. Futuropolis. Bergström And Boyle/Big O, 1979.

STUDY.COM, study.com/academy/lesson/architecture-parlante-definition-examples.html.

Superstudio, et al. “Superstudio on Mindscapes.” Design Quarterly, no. 89, 1973, p. 17., doi:10.2307/4090788.

“Twelve Cautionary Tales.” R / D, www.readingdesign.org/twelve-cautionary-tales.