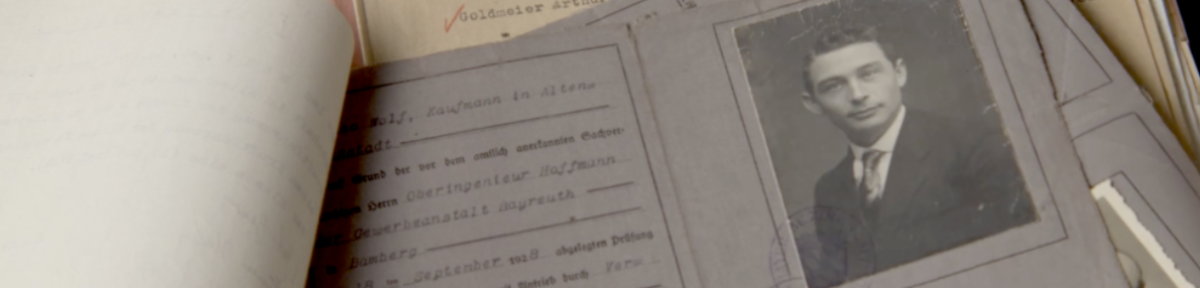

Germany has an exemplary culture of remembrance, but the 13 Driver’s Licenses story is unique even for Germany. High school students begin their project with no knowledge but the names and photos on the discovered driver’s licenses. During nine months of research, they experience intense emotions from curiosity and excitement to intense heartache and grief when they find out that some of the driver’s license holders had been murdered in the Holocaust . . . to elation at finding out that some had escaped, the fear of rejection when contacting the surviving descendants, and finally joy at inviting and meeting them and forming budding friendships. The story is equally emotional for the surviving descendants. Many had no knowledge of their ancestors’ past in Germany as they had never talked about their experience—too painful had been the memories of families and friends being murdered, and of escaping and leaving everything behind. The students’ research gave them their family history back.

The students’ research had far-reaching impact—on the students themselves, on the town, on the descendants, and on Jewish/German relations. Modern-day Germans and Jewish descendants were reunited in remembrance, reconciliation, and friendship.

The story is relevant today as an example of remembrance that could be applied to contexts in other countries, where war crimes and crimes against humanity have been committed and not been processed. It is ultimately a story of hope that a tragic past can be transcended and that reconciliation is possible.

Artistic Approach

In “13 Driver’s Licenses” (13 DL), much of the story takes place in the picturesque Franconian region of Germany. In a peaceful town, Lichtenfels, it is hard to imagine today what atrocities took place against its Jewish citizens during the Nazi regime. The film will show the colorful and historic town in the present time, and also black-and-white archival images of the dark Nazi era. I am trained as a visual artist, and therefore my goal is to tell stories visually.

For this project, it is truly fortunate that we are able to work with a renowned cinematographer, Mark Raker, an Emmy and Peabody Awards recipient. For documentaries, he has worked with directors such as Michael Moore and Martin Scorsese; his superb cinematographic skills are also evident in the many high-end commercials he has filmed. He is a master of light. Before we started the production, he inquired what kind of mood he should create with lighting. “Sad?” he asked first. My response was that the film, although it focuses on a dark era of history, the major tenor is hope and a positive light for the future. We reached an agreement. When he was asked by a local journalist in Germany, this was what he said about his role in the production: “In photographing 13 DL, I wanted the light that falls on the town and the people to not just reflect the condition of nature, but to reflect the condition of their souls. To bring out the hope and promise and healing that has been so bravely displayed.” The collaboration with this cinematographer has been vital in this project. He has also served as the colorist. He is the most appropriate person for color grading as he knows what the intention was when the raw footage was captured.

In terms of music, our collaborator is Dr. David B. Smith. He is trained as a classical music composer, and his talent is magnificent. For the 13 DL short film, we first discussed the overarching theme: guilt and transcendence. We agreed that historically, Mozart’s “Contessa Perdono” (Marriage of Figaro) and Beethoven’s Emperor Piano Concerto No. 5, Second Movement sublimely expressed this spirit and could serve as influences for the music in the film. We then focused on the mood for each segment of the film. Dr. Smith’s music beautifully complements the visuals, deepens each of the emotions, and manages to express and make coherent the wide range of feelings and themes in the film that are often present simultaneously, such as sadness and joyfulness, grief and forgiveness, tragedy and hope. The story and music are complex. David B. Smith has masterfully translated this complexity into deeply touching and truly transcending music.

We have also successfully incorporated the sound of the town, the sound of church bells, and the sound of regional birds, which will continue to be important parts of the feature-length film—as will be folly work for the planned scenes of reenactment.

Filmmaker’s Background

I was born in Tokyo, Japan, in particular, near the district of Seijo, Setagaya, which is known for Toho Film Studios, which produced many of the works directed by Akira Kurosawa. Within a walking distance from my parents’ house, there also existed Mifune Productions, which was funded by a renowned actor, Toshiro Mifune. On his company property, there were TV sets of the Edo Period (1603 – 1867). The general public was allowed to enter the sets as long as we didn’t disturb the filming in progress. I grew up watching actors in their samurai costumes walking around in my neighborhood. I recall observing film production as a child. Everyone on the sets was focused, including even us spectators. I felt we all lived in the historic time period together at that moment. This impacted my upbringing.

There were also some visual artists among my relatives. A painters’ couple left Japan for Sienna, Italy in the 1960’s. The destination was determined because the uncle was fascinated by the color, Burnt Sienna. His abstract oil paintings and stained glass works were recognized in the region, and he eventually became an honored citizen of the town. To me, it was intriguing to hear the relatives’ stories overseas and artistic vision whenever they returned to Japan to visit. This was perhaps the beginning of my fascination for different cultures.

I myself was also trained as a visual artist. After I left Japan, I attended the University of Georgia in Athens, GA around 1990. In the art department, I was able to paint, generate computer graphics, shoot 8 mm film, and edit transferred video footage digitally. One of the painting faculty, James Herbert was well-known as an art/experimental filmmaker. Therefore, my first experience of filmmaking was focusing on artistic images. He is also known for directing music videos for the then-world-famous rock band, REM, which came out of Athens.

I hold an MFA in painting from Parsons School of Design in New York. While I was a graduate student, I interned at the Downtown Community TV Center. That’s where I became interested in documentaries. Then, after freelancing as a camera operator or a camera assistant, I started working for NHK, public television of Japan at its New York branch. While at NHK, I gained training in researching, coordinating, and eventually directing public TV documentaries. Now, as a college professor, I work on independent films. I aim to bring an artistic and poetic quality to my films, even documentaries. In the “13 Driver’s Licenses” project, all of these experiences are reflected: the artistic approach, cultural sensitivity, and the fascination with history.

Success as an artist is to deeply touch and inspire people—to elevate them to higher plains and show what is possible. The Holocaust is a very challenging theme, yet through the project, I feel we are showing paths on how to process a horrendous past and possibly achieve transcendence for a better future.

The story takes place in my wife’s hometown, where I frequently visit.