This class was a field trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a first for me, I was very much enamored with the grandiosity of the establishment and equally amazed by its impressive portfolio, featuring history’s finest relics.

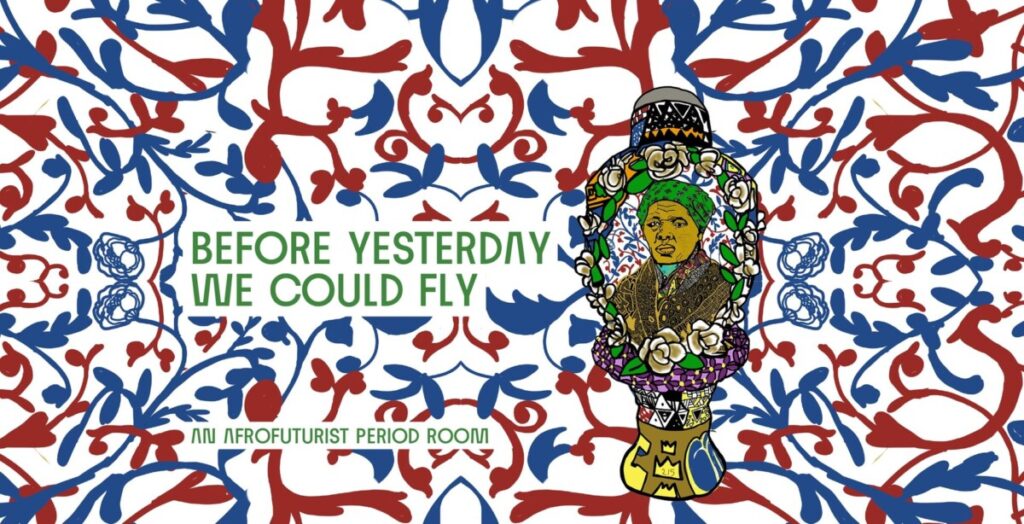

For the class, our first stop was an exhibit titled “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room Bulletin”, orchestrated by a collective of Black artist such as; California-born Nigerian, Ini Archibong, South African ceramist, Andile Dyavalne, Haitian sculptor, Fabiola Jean-Louis, African-American author and illustrator, John Jennings, and Kenyan visual artist, Cyrus Kabiru. As implied in its name, this exhibit fully centers on Afrofuturism, a term coined by American author and cultural critic, Mark Dery, who defined it as “a speculative fiction that treats African American themes and addresses African American concerns in the context of the 20th century technoculture.” However, the term’s meaning has evolved to be a cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science and history, that explores the developing intersection of the African diaspora culture with science and technology.

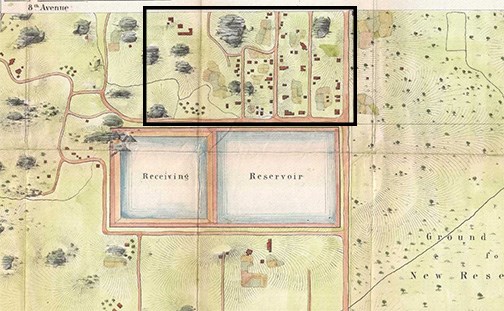

The exhibit is largely inspired by Seneca Village, a predominantly Black and vibrant, 19th Century village, located in present-day Central Park. The settlement was synonymous with Black prosperity and flourishing but unfortunately, ended up suffering the same fate as its much latter Oklahoman successor, Tulsa. Set within the context of a “domestic space”, the exhibit features an assembling of objects and furnishings obtained from “fragmented history remains, rejecting the notion of one historical period”. These exhibit is a consolidation and a celebration of interconnected African and African-American diasporic beliefs viewed through the lenses of Black imagination, excellence and self-determination.

Amongst the beautiful pieces featured in this exhibit, they were a few in particular that caught my attention and particularly resonated to. The first is the Prestige Stool: Leopard from the Bamileke and Bamum tribe of Cameroon. A 19 by 16 in, wooden sculpture, wrapped in printed cotton cloth and adorned with glass beads and cowry shell, this piece was a personal standout of the exhibit. The once united Bamileke and Bamum, also known as People of the Grassfields, are the largest ethnic groups in Cameroon, with the Bamileke being native to the West and the Bamum to the East. Both tribes are known for their culture and expression through color and their masterful beadwork as featured in this piece. In our culture the Prestige Tool is exactly what its name indicates, it represents power, it is usually used during royal ceremony and is only sat on by the Fon, the Bamileke ruler, the notables, and elders. The stool is an indication of how high one is in the hierarchy within the members of the court. The reason I immediately gravitated to this object after laying my eyes on it is because as a Bamilke from my maternal side of my family, I was proud to see my culture take such a prominent position in this exhibit and how it contributes to furthering the conversation on the progression of the diaspora through the lens of Afrofuturism.

Made of inked paper and ornamented with Swarovski crystals, lapis lazuli, labradorite brass and resin, Fabiola Jean-Louis’ “Justice for Ezili” sculpture was another personal highlight of the exhibit. As a passionate of ancient world history, cultures and religion, this piece is an homage to the Haitain lwa Erzulie Dantor. Vodun, in its prime, originated from the Dahomey Kingdom, present-day Benin, West Africa, and after the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the traditional African religion was adopted by Haitian people in the Caribbean. Haitian Voodoo deities are known as Lwa, which is variation of the French word, “Loi”, meaning “Law” in English. These deities are divided into nanchons (“nations”) or fanmi (“Family”) namely Guede, Rada and Petro, with the Erzulie lwa family belonging to the latter two. Lwas operate as counterparts of each other between nanchons and between their respective family, in the case of the lwa honored in Jean- Louis’ sculpture, Erzulie Dantor is the Petro aspect of the Erzulie family. Often depicted as a fearsome Black woman, she is the fierce protector lwa of women and children and is known to bless her worshippers with spiritual knowledge to help them as they navigate the material realm. As a passionate of Haitian mythology, I was attracted to this object because it is a testimony to the traditional practices my African ancestors have been practicing during pre-Colonial times. Furthermore, the fact Erzulie Dantor’s brooch was pinned to the regal attire of a time period she predates, highlights the transcendence of traditional African beliefs and how the celebration of Blackness in all its forms, is not limited to the bounds of time itself.

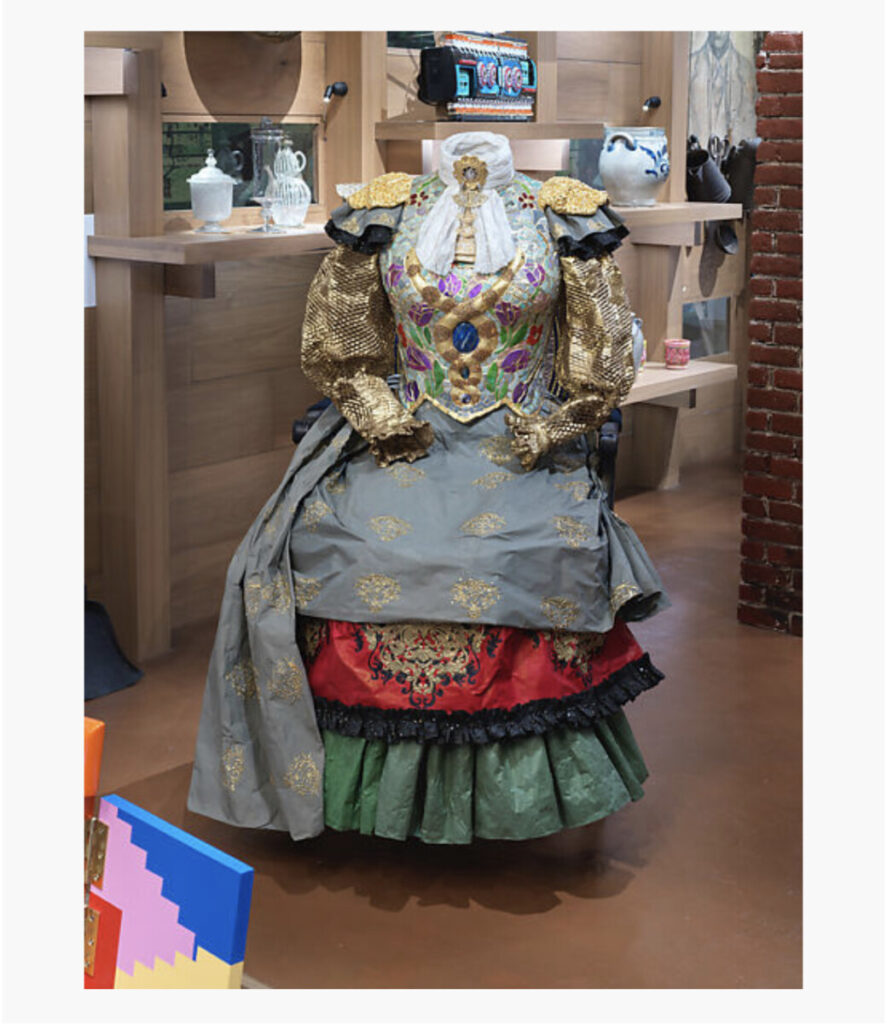

A fashion aficionado, I could not help but make my way down to the lower level of the museum, where was held the first part of the fashion/costume, titled “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion.” An exhibit featuring archival pieces from the most iconic American fashion designers the likes of Ralph Lauren, Thom Browne, Anna Sui, Vera Wang, Charles James, Tory Burch, Halston, Donna Karan Oscar de la Renta. I further appreciated that the exhibit was inclusive to prolific Black fashion designer both alive and dead such as Patrick Kelly, Christopher John Rogers, Pyer Moss, KidSuper, Hood By Air, Savage X Fenty and Dapper Dan of Harlem. Many of these designers rank among my personal favorites for whom I hold a great deal of admiration, however, a profound and delightful feeling of pride and content filled me up when I laid eyes on the La Vie by CK number

La Vie by CK is a Los Angeles based fashion brand founded by Cameroonian born designer, Claude Kameni. Kameni is known for her stunning African-inspired designs and garments, and her use of eye catching and colorful prints such as the African wax prints. Inspired by the batik or wax-resist cloth from Indonesia, these fabrics have found immense popularity and wide use in West and Central Africa. Kameni’s exhibit dress is a plunging neckline, mermaid silhouette dress made of cotton with a “pattern arranged to complement the curves of the figure and accentuate the flowing tiers of the skirt.”

As a fellow Cameroonian with fashion aspirations, I was extremely happy to see African contemporary art being positioned on such a prestigious stage for the world to see. Kameni is a 27 years-young designer not even a decade into her career and she is already featured at the MET amongst the greats. I felt extremely happy to witness this career milestone so early in her career as well as inspiring for me to pursue my fashion dreams to maybe someday be featured within the halls of the MET.