Creative Activities for Engaging Students

In her book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, bell hooks writes about the ways that the worst classrooms of her own educational experience solidified for her a pedagogy that foregrounds excitement. She writes, “Critical reflection on my experience as a student in unexciting classrooms enabled me not only to imagine that the classroom could be exciting but that this excitement could co-exist with and even stimulate serious intellectual and/or academic engagement” (7). I’ve long maintained that low-stakes, playful activities provide space for students to “try on” new ideas or examine complicated ones. Below are some of my favorite classroom activities.

Meet-Match-Teach

I like to use this activity on the second day of the semester, because it helps students become familiar with their peers even as they become experts in a specific area of knowledge and assume the responsibility for teaching that information to the rest of the class.

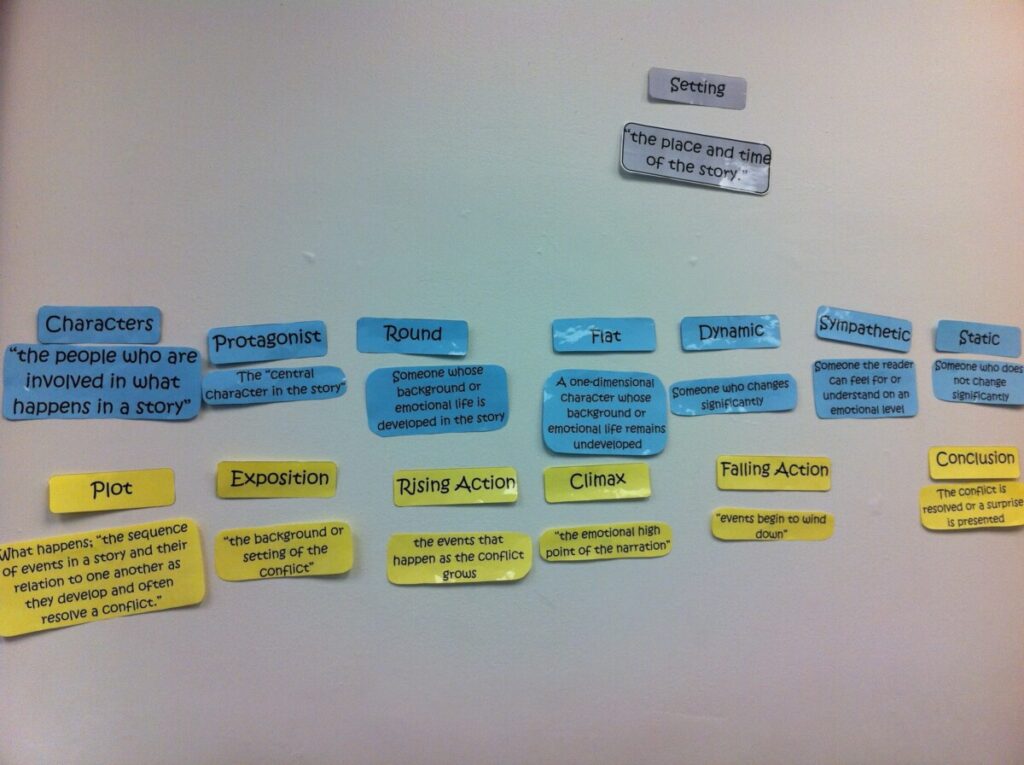

For this lesson, students come to class having already read an assigned essay by Ann Charters on the elements of fiction (plot, theme, point of view, characters, style, and setting). At the start of class, students receive two cards or signs; one has a term from Charters’s essay, and the other has a definition. Each student’s term and definition will not match. By walking around the room and engaging other students, they must find the correct definition for their term, and the correct term for their definition, leaving each student with two cards at the end: a matching term and definition.

Cards are color coded, so when students have found the matching term and definition, they can create groups based on the color of their cards; there are six groups, each one focused on a single element of fiction. These groups work together to determine the best way to teach their element to the rest of the class, using as an example a text they think most of the class will know. Each group affixes the signs to the wall with Bluestick.

This activity was very successful; students learned the terms quickly and were able to apply them to the assigned readings. Students also became comfortable with one another more quickly, engaging with one another during class discussion, rather than simply responding to my questions alone. Later in the semester, I may use these cards again to demonstrate that these definitions can change as we read different texts; when we discuss a graphic novel, for instance, students may work together to revise the definitions we had been working with all semester to accommodate a new genre. They can then put these new revised definitions on the wall next to the original definition and the term.

Frankenstein Bingo

Because the elevated style of Mary Shelley’s novel can be intimidating for some students, I find that games can help to reduce the stress and to provide areas of access where the students can gain footholds. I use a bingo game to help students identify important themes and how they relate to other elements of fiction (like setting, style, characterization, and point of view), which helps them to gain a level of familiarity with this difficult text.

To play the game, students begin by selecting one sentence to write on an index card I distribute. There is an alphanumeric code at the top of each card which corresponds to a specific chapter of the text. Students must select their quotation according to this general direction. They submit their cards to me (I often ask them to generate more than one), and I draw from them at random. Students then work in teams to determine if any particular quotation can fill a spot on their bingo card. In order to do this, a quotation must represent an intersection between the specific theme across the top of the card, and the element of fiction listed in the column on the left. When a team has a line completed, they yell “BINGO!” and must defend their readings of each quotation to the rest of the class.

This activity gets students working in groups to understand individual sentences of a difficult text. The focus on a single sentence isolates it for the students, who can then begin to put it into the context of concepts they already know. Having to defend their readings also develops their argumentation skills, and teaches them how to analyze quotations in ways that support their overall purpose. Of course, this latter skill is incredibly important when writing formal papers. Click here to see the Bingo cards.

Jeopardy

I use a template I found online, and create Jeopardy games to use for review. Students work in teams to answer questions (or, technically, to answer in the form of a question). The template allows for five categories of increasingly difficult questions. I populate the template with questions and answers based on the purpose of the review.

Debates

In my composition courses and in my literature courses, I use debates to provide a structure for argumentation. I choose a polarizing question, assign students to a team, and give them time to prepare their statements. The debates encourage team work, careful reading, making connections among various readings or different elements of fiction, and effective quotation usage, and they introduce the idea of addressing one’s opponents when defending one’s own argument. Students may only be responsible for one round of a debate, so their work is focused on just one part of the whole, but they are part of a team that they want to see win, so they need to understand how their individual statement fits into the larger argument or purpose.