Table of Contents

LESSON 5: Gothic buildings, vernacular art, and genre painting.

WHAT TO READ, WATCH, OR LISTEN TO BEFORE CLASS.

From your textbook, American Encounters:

- Chapter 6: “Gothic America,” pages 176 to 180. Focus on Thomas Cole’s The Architect’s Dream; Lyndhurst by architect A. J. Davis; and under “Egyptian Revival,” the Washington Monument. Compare Lyndhurst to the Gothic cottage by A. J. Downing on page 249.

- Browse the next two sections on quilts and folk art, pages 180 to 192. Focus on the three paragraphs on page 184-185 under the heading “Folk and Vernacular Traditions.” This section raises hard questions about how we categorize American art. With that in mind, browse the section on the Plains cultures, pages 211 to 221. Focus on Chief Máh-to-tóh-pa, pages 213 to 216, who represented himself.

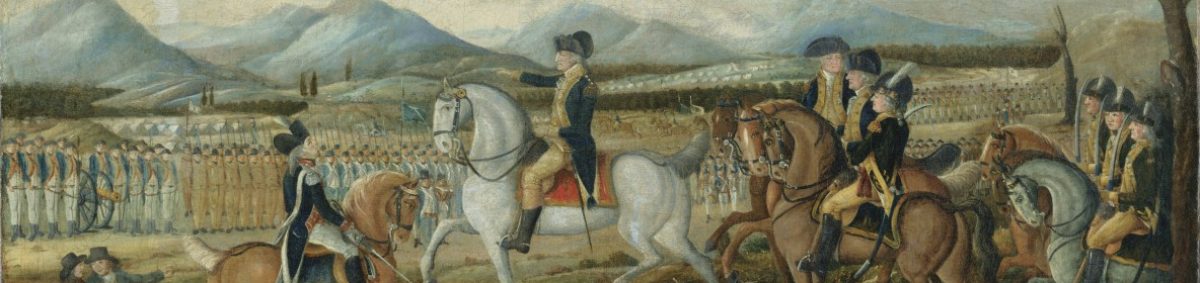

- Browse “Genre Painting,” pages 193 to 207. Focus on William Sidney Mount and Richard Caton Woodville. Then go to Chapter 7, pages 225 to 228, and look at paintings by George Caleb Bingham. In class, we will try to write a simple description or definition of American genre painting that considers who made them, who bought them, and what they were about.

From the Metropolitan Museum:

A slide show of drawings and watercolors by architect A. J. Davis (see page 177 in American Encounters.)

From the Seeing America project by Smarthistory:

- Video (4 min.): Thomas Cole’s The Architect’s Dream, 1840.

- In-depth look at the construction of the Washington Monument (1833-88) on the national mall in Washington, DC.

- Video (6 min.): Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848.

From Google Art and Culture:

Mrs. Abraham White and Daughter Rose, 1808-09, by African-American painter Joshua Johnson; The Wounded Indian, 1848-50, by Neoclassical sculptor Peter Stephenson, and Facing the Enemy, 1845, by genre painter Francis William Edmonds. All three are in the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia.

WHAT TO SEE, SKIM, OR SAMPLE AS TIME ALLOWS.

Contemporary portals into this lesson:

- Review “The Colonial Church”, page 108 (one paragraph and large photo) in American Encounters. One of the best examples still standing is St. Paul’s Chapel at Broadway and Fulton St. in Manhattan.

- The country’s first Gothic Revival church, Trinity Church on Wall Street, is in the same lower Manhattan parish.

- Both are now National Historic Landmarks. Attached are the nomination forms submitted in 1976 and 1977 that document the buildings’ history and architectural significance. Congress passed the Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

LESSON 6: Nature, History and the Landscape.

WHAT TO READ, WATCH, OR LISTEN TO BEFORE CLASS.

From your textbook, American Encounters:

- In Chapter 7, read “Living Traditions and Icons of Defeat,” pages 222-225. Focus on Durand’s painting, “Progress,” 1853, and Crawford’s sculpture, “Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization,” 1856.

- Browse “Native Arts of Alaska,” pp. 230-239. Focus on objects from the Tlingit culture.

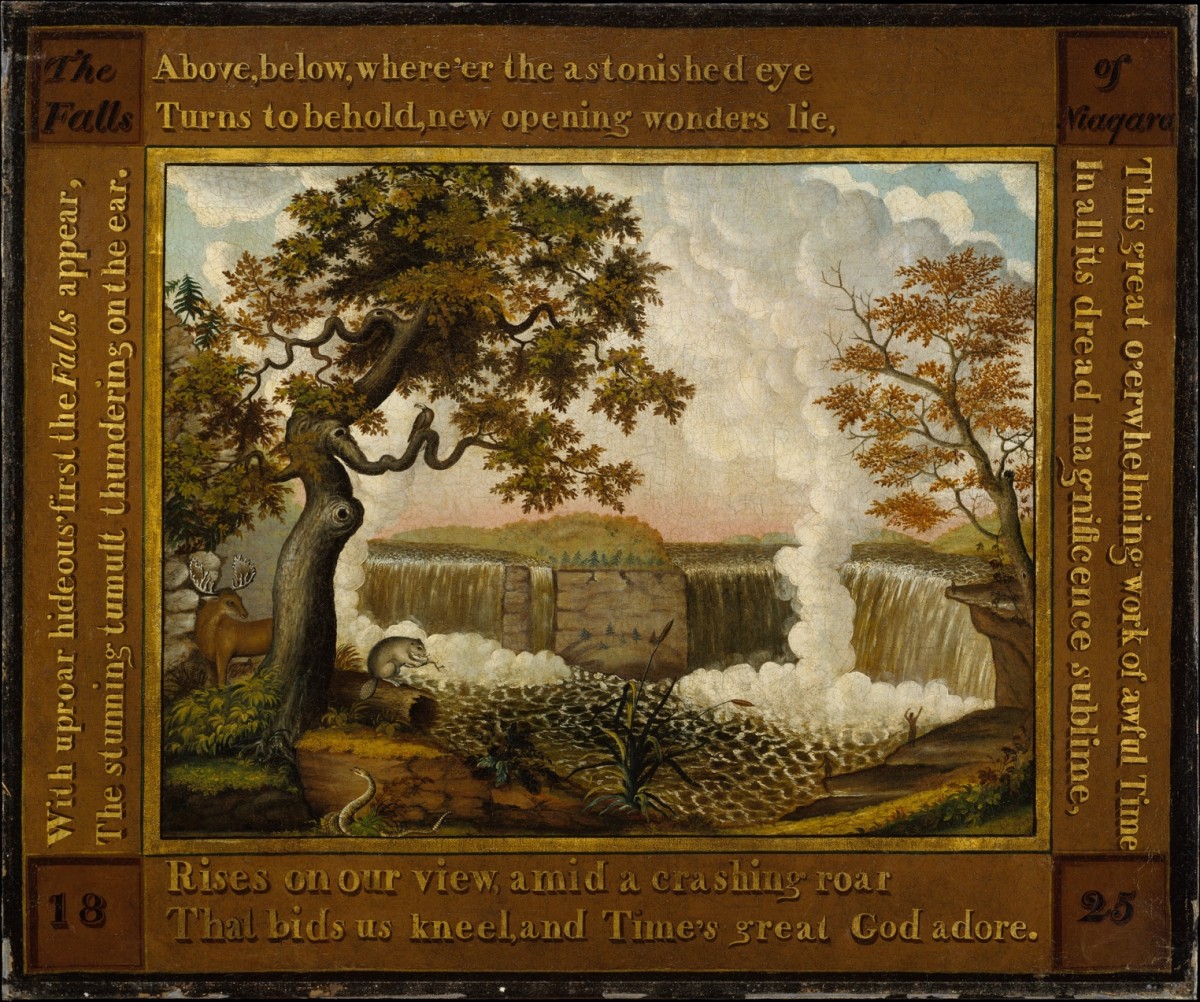

- In Chapter 8, focus on the introduction, p. 241. Then browse the long section on landscape painting, pp. 241-268. Focus on the concepts of the Picturesque and the Sublime; Edward Hicks, The Falls of Niagara, 1825; Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire, 1834-36; and Asher B. Durand’s Kindred Spirits, 1849.

- Review the terms “folk,” “vernacular,” and “visionary artist” in the Glossary, p. 656 ff. In class, we will define and discuss the term “academic art.”

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Slideshow of Hudson River School including paintings by Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand.

From the New York Times:

Read “At the Met, a Riveting Testament…” In it, Roberta Smith touches on all of the problems of the labels we attach to works from anyone who didn’t go to art school. This is exactly the same problem we tackled last week in “Folk and Vernacular Traditions,” p. 184-185. Visit the Met online for the Fall 2018 “History Refused to Die” exhibition.

From the Seeing America project by Smarthistory:

- Video (7 min.): Edward Hicks, Peaceable Kingdom, 1826.

- Video (5 min.): Thomas Cole’s The Oxbow, 1836. The painting is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- An in-depth look at Central Park (Olmsted and Vaux, c. 1857-1876). Browse the historic maps and photos. Search the page for “picturesque” and read each paragraph for its meaning in context (there are three). Review “picturesque” on pp. 243-248 in your textbook.

- Video (6 min.): Seneca Village was an African-American community displaced by Central Park. Mr. and Mrs. Lyons, above, lived there until about the time these portraits were made in 1860.

- Video (6 min.): Clarissa Rizal’s Resilience Robe (Compare to the Aleut robe, p. 237.) Review “Tlingit Art, Ownership, and Meaning Across the Generations,” p. 236. (Pronunciation of Tlingit.)

WHAT TO SEE, SKIM, OR SAMPLE AS TIME ALLOWS.

Contemporary portals to nature: artists working with land, water and sky:

- Video (7 min.): Earthworks by Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, earthwork. 1970; and

- Video (5 min.): James Turrell, Skyscape, the way of color, room with oculus. 2009.

- Video (6 min.): “An unflinching memorial to Civil Rights martyrs,” Blood and Meat, painted assemblage, 1992, by Thornton Dial.

LESSON 7: Photography, Emancipation, and Memorials

WHAT TO READ, WATCH, OR LISTEN TO BEFORE CLASS.

From your textbook, American Encounters:

- In Chapter 8, browse “Daguerreotypes and Early Photography,” and “War and Peace,” pp. 268-275. Focus on the difference between a daguerreotype and the wet-plate process; the Zealy daguerreotype “Jack”; Mathew Brady’s enterprises; and images from the war itself, pp. 271-275: photographs, a print, and a painting.

- In Chapter 9, read “The Mixed Legacy of Emancipation: Monuments to Freedom,” pp. 284 to 287. Focus on John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman, 1863; and Lucinda Ward Honstain’s quilt, 1867.

- Focus on Winslow Homer, Dressing for the Carnival, 1877, p. 288-289.

- Focus on Augustus St. Gaudens, Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw, 1884-1897 and watch about 90 seconds from the 1989 film Glory, that represents the 54th Massachusetts infantry heading into battle.

- In Chapter 11, see St. Gaudens, Memorial to Clover Adams, p. 356, and read “Victorian into Modern: Exploring the Boundaries between Mind and World,” pp. 358-359.

From the Metropolitan Museum:

- Two portraits of Frederick Douglass: A daguerreotype (1855) and an albumen print photograph (c. 1880).

- Winslow Homer, Veteran in a New Field, 1865.

From Seeing America by Smarthistory:

- An in-depth look at Hiram Powers, Greek Slave, 1843, and p. 174-175. (Also review Peter Stephenson, Wounded Indian, 1850, from lesson 5. Both of these were exhibited together in London in 1851 and were noted in the press as being “representative” of America’s problems with both slavery and the treatment of Native Americans.)

- Video (6 min.): “Representing Freedom during the Civil War,” Ward’s Freedman, 1863.

- An in-depth look: “Putting Liberty Front and Center,” Eastman Johnson’s Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862.

What to see, skim, or sample as time allows.

From Seeing America, two surprising objects from the post-war era:

- Video from (6 min.): “Carving out a life after slavery,” about a remarkable work of furniture/sculpture attributed to freedman William Howard, c. 1870.

- Video (5 min.): A “snake jug” c. 1865, offers rude commentary on politicians.

Contemporary portals to this lesson – monuments from the late 20th century:

- Video from Seeing America: (7 min.) Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982. A minimalist memorial to the war dead that established a very quiet, meditative new form of American monument.

- In American Encounters, “The AIDS Crisis,” pp. 637-639, on the NAMES quilt, a community art project and memorial, pictured on the mall in Washington, D.C. in 1996.