Contents [hide]

- 1 The Healthy Life

- 2 What Is Health Psychology?

- 3 Stress And Health

- 4 Protecting Our Health

- 5 The Importance Of Good Health Practices

- 6 Psychology And Medicine

- 7 Being A Health Psychologist

- 8 The Future Of Health Psychology

- 9 Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being

- 10 Introduction

- 11 Types of Happiness

- 12 Causes of Subjective Well-Being

- 13

- 14

- 15 Societal Influences on Happiness

- 16 Adaptation to Circumstances

- 17 Outcomes of High Subjective Well-Being

- 18 Measuring Happiness

- 19 Some Ways to Be Happier

The Healthy Life

By Emily Hooker and Sarah Pressman

University of Calfornia, Irvine

Our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors play an important role in our health. Not only do they influence our day-to-day health practices, but they can also influence how our body functions. This module provides an overview of health psychology, which is a field devoted to understanding the connections between psychology and health. Discussed here are examples of topics a health psychologist might study, including stress, psychosocial factors related to health and disease, how to use psychology to improve health, and the role of psychology in medicine.

Learning Objectives

- Describe basic terminology used in the field of health psychology.

- Explain theoretical models of health, as well as the role of psychological stress in the development of disease.

- Describe psychological factors that contribute to resilience and improved health.

- Defend the relevance and importance of psychology to the field of medicine.

What Is Health Psychology?

Today, we face more chronic disease than ever before because we are living longer lives while also frequently behaving in unhealthy ways. One example of a chronic disease is coronary heart disease (CHD): It is the number one cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2013). CHD develops slowly over time and typically appears midlife, but related heart problems can persist for years after the original diagnosis or cardiovascular event. In managing illnesses that persist over time (other examples might include cancer, diabetes, and long-term disability) many psychological factors will determine the progression of the ailment. For example, do patients seek help when appropriate? Do they follow doctor recommendations? Do they develop negative psychological symptoms due to lasting illness (e.g., depression)? Also important is that psychological factors can play a significant role in who develops these diseases, the prognosis, and the nature of the symptoms related to the illness. Health psychology is a relatively new, interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on these very issues, or more specifically, the role of psychology in maintaining health, as well as preventing and treating illness.

Consideration of how psychological and social factors influence health is especially important today because many of the leading causes of illness in developed countries are often attributed to psychological and behavioral factors. In the case of CHD, discussed above, psychosocial factors, such as excessive stress, smoking, unhealthy eating habits, and some personality traits can also lead to increased risk of disease and worse health outcomes. That being said, many of these factors can be adjusted using psychological techniques. For example, clinical health psychologists can improve health practices like poor dietary choices and smoking, they can teach important stress reduction techniques, and they can help treat psychological disorders tied to poor health. Health psychology considers how the choices we make, the behaviors we engage in, and even the emotions that we feel, can play an important role in our overall health (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Taylor, 2012).

Health psychology relies on the Biopsychosocial Model of Health. This model posits that biology, psychology, and social factors are just as important in the development of disease as biological causes (e.g., germs, viruses), which is consistent with the World Health Organization (1946) definition of health. This model replaces the older Biomedical Model of Health, which primarily considers the physical, or pathogenic, factors contributing to illness. Thanks to advances in medical technology, there is a growing understanding of the physiology underlying the mind–body connection, and in particular, the role that different feelings can have on our body’s function. Health psychology researchers working in the fields of psychosomatic medicine and psychoneuroimmunology, for example, are interested in understanding how psychological factors can “get under the skin” and influence our physiology in order to better understand how factors like stress can make us sick.

Stress And Health

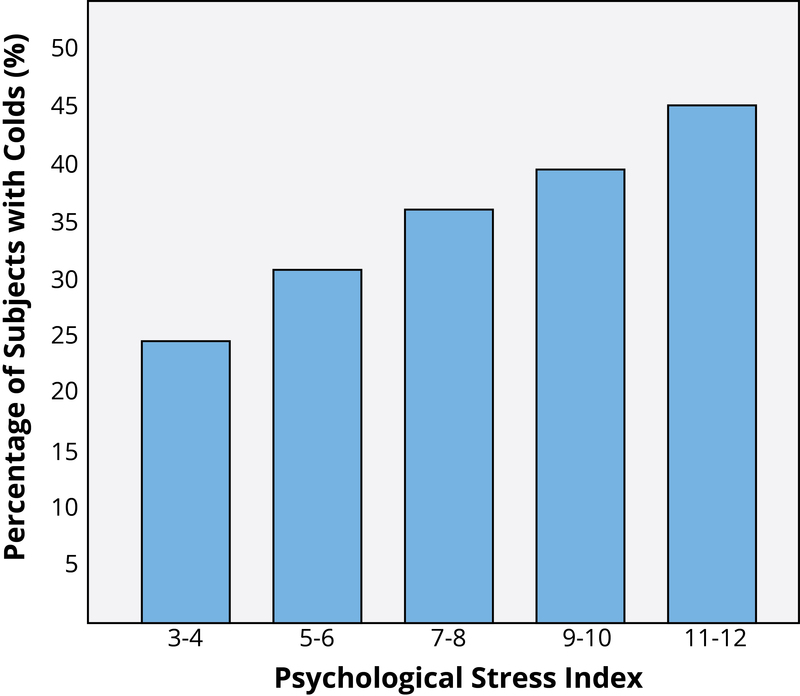

You probably know exactly what it’s like to feel stress, but what you may not know is that it can objectively influence your health. Answers to questions like, “How stressed do you feel?” or “How overwhelmed do you feel?” can predict your likelihood of developing both minor illnesses as well as serious problems like future heart attack (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). (Want to measure your own stress level? Check out the links at the end of the module.) To understand how health psychologists study these types of associations, we will describe one famous example of a stress and health study. Imagine that you are a research subject for a moment. After you check into a hotel room as part of the study, the researchers ask you to report your general levels of stress. Not too surprising; however, what happens next is that you receive droplets of cold virus into your nose! The researchers intentionally try to make you sick by exposing you to an infectious illness. After they expose you to the virus, the researchers will then evaluate you for several days by asking you questions about your symptoms, monitoring how much mucus you are producing by weighing your used tissues, and taking body fluid samples—all to see if you are objectively ill with a cold. Now, the interesting thing is that not everyone who has drops of cold virus put in their nose develops the illness. Studies like this one find that people who are less stressed and those who are more positive at the beginning of the study are at a decreased risk of developing a cold (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1991; Cohen, Alper, Doyle, Treanor, & Turner, 2006) (see Figure 1 for an example).

Importantly, it is not just major life stressors (e.g., a family death, a natural disaster) that increase the likelihood of getting sick. Even small daily hassles like getting stuck in traffic or fighting with your girlfriend can raise your blood pressure, alter your stress hormones, and even suppress your immune system function (DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988; Twisk, Snel, Kemper, & van Machelen, 1999).

It is clear that stress plays a major role in our mental and physical health, but what exactly is it? The term stresswas originally derived from the field of mechanics where it is used to describe materials under pressure. The word was first used in a psychological manner by researcher Hans Selye. He was examining the effect of an ovarian hormone that he thought caused sickness in a sample of rats. Surprisingly, he noticed that almost any injected hormone produced this same sickness. He smartly realized that it was not the hormone under investigation that was causing these problems, but instead, the aversive experience of being handled and injected by researchers that led to high physiological arousal and, eventually, to health problems like ulcers. Selye (1946) coined the term stressor to label a stimulus that had this effect on the body and developed a model of the stress response called the General Adaptation Syndrome. Since then, psychologists have studied stress in a myriad of ways, including stress as negative events (e.g., natural disasters or major life changes like dropping out of school), as chronically difficult situations (e.g., taking care of a loved one with Alzheimer’s), as short-term hassles, as a biological fight-or-flight response, and even as clinical illness like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It continues to be one of the most important and well-studied psychological correlates of illness, because excessive stress causes potentially damaging wear and tear on the body and can influence almost any imaginable disease process.

Protecting Our Health

An important question that health psychologists ask is: What keeps us protected from disease and alive longer? When considering this issue of resilience (Rutter, 1985), five factors are often studied in terms of their ability to protect (or sometimes harm) health. They are:

- Coping

- Control and Self-Efficacy

- Social Relationships

- Dispositions and Emotions

- Stress Management

Coping Strategies

How individuals cope with the stressors they face can have a significant impact on health. Coping is often classified into two categories: problem-focused coping or emotion-focused coping (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Problem-focused coping is thought of as actively addressing the event that is causing stress in an effort to solve the issue at hand. For example, say you have an important exam coming up next week. A problem-focused strategy might be to spend additional time over the weekend studying to make sure you understand all of the material. Emotion-focused coping, on the other hand, regulates the emotions that come with stress. In the above examination example, this might mean watching a funny movie to take your mind off the anxiety you are feeling. In the short term, emotion-focused coping might reduce feelings of stress, but problem-focused coping seems to have the greatest impact on mental wellness (Billings & Moos, 1981; Herman-Stabl, Stemmler, & Petersen, 1995). That being said, when events are uncontrollable (e.g., the death of a loved one), emotion-focused coping directed at managing your feelings, at first, might be the better strategy. Therefore, it is always important to consider the match of the stressor to the coping strategy when evaluating its plausible benefits.

Control and Self-Efficacy

Another factor tied to better health outcomes and an improved ability to cope with stress is having the belief that you have control over a situation. For example, in one study where participants were forced to listen to unpleasant (stressful) noise, those who were led to believe that they had control over the noise performed much better on proofreading tasks afterwards (Glass & Singer, 1972). In other words, even though participants did not have actual control over the noise, the control belief aided them in completing the task. In similar studies, perceived control benefited immune system functioning (Sieber et al., 1992). Outside of the laboratory, studies have shown that older residents in assisted living facilities, which are notorious for low control, lived longer and showed better health outcomes when given control over something as simple as watering a plant or choosing when student volunteers came to visit (Rodin & Langer, 1977; Schulz & Hanusa, 1978). In addition, feeling in control of a threatening situation can actually change stress hormone levels (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Believing that you have control over your own behaviors can also have a positive influence on important outcomes like smoking cessation, contraception use, and weight management (Wallston & Wallston, 1978). When individuals do not believe they have control, they do not try to change. Self-efficacy is closely related to control, in that people with high levels of this trait believe they can complete tasks and reach their goals. Just as feeling in control can reduce stress and improve health, higher self-efficacy can reduce stress and negative health behaviors, and is associated with better health (O’Leary, 1985).

Social Relationships

Research has shown that the impact of social isolation on our risk for disease and death is similar in magnitude to the risk associated with smoking regularly (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). In fact, the importance of social relationships for our health is so significant that some scientists believe our body has developed a physiological system that encourages us to seek out our relationships, especially in times of stress (Taylor et al., 2000). Social integration is the concept used to describe the number of social roles that you have (Cohen & Wills, 1985), as well as the lack of isolation. For example, you might be a daughter, a basketball team member, a Humane Society volunteer, a coworker, and a student. Maintaining these different roles can improve your health via encouragement from those around you to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Those in your social network might also provide you with social support (e.g., when you are under stress). This support might include emotional help (e.g., a hug when you need it), tangible help (e.g., lending you money), or advice. By helping to improve health behaviors and reduce stress, social relationships can have a powerful, protective impact on health, and in some cases, might even help people with serious illnesses stay alive longer (Spiegel, Kraemer, Bloom, & Gottheil, 1989).

Dispositions and Emotions: What’s Risky and What’s Protective?

Negative dispositions and personality traits have been strongly tied to an array of health risks. One of the earliest negative trait-to-health connections was discovered in the 1950s by two cardiologists. They made the interesting discovery that there were common behavioral and psychological patterns among their heart patients that were not present in other patient samples. This pattern included being competitive, impatient, hostile, and time urgent. They labeled it Type A Behavior. Importantly, it was found to be associated with double the risk of heart disease as compared with Type B Behavior (Friedman & Rosenman, 1959). Since the 1950s, researchers have discovered that it is the hostility and competitiveness components of Type A that are especially harmful to heart health (Iribarren et al., 2000; Matthews, Glass, Rosenman, & Bortner, 1977; Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996). Hostile individuals are quick to get upset, and this angry arousal can damage the arteries of the heart. In addition, given their negative personality style, hostile people often lack a heath-protective supportive social network.

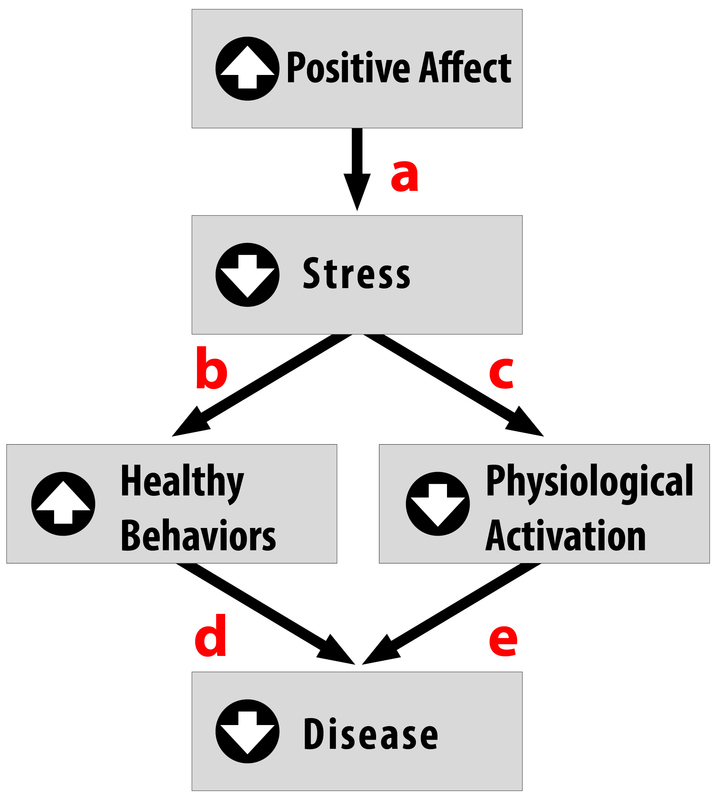

Positive traits and states, on the other hand, are often health protective. For example, characteristics like positive emotions (e.g., feeling happy or excited) have been tied to a wide range of benefits such as increased longevity, a reduced likelihood of developing some illnesses, and better outcomes once you are diagnosed with certain diseases (e.g., heart disease, HIV) (Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Across the world, even in the most poor and underdeveloped nations, positive emotions are consistently tied to better health (Pressman, Gallagher, & Lopez, 2013). Positive emotions can also serve as the “antidote” to stress, protecting us against some of its damaging effects (Fredrickson, 2001; Pressman & Cohen, 2005; see Figure 2). Similarly, looking on the bright side can also improve health. Optimism has been shown to improve coping, reduce stress, and predict better disease outcomes like recovering from a heart attack more rapidly (Kubzansky, Sparrow, Vokonas, & Kawachi, 2001; Nes & Segerstrom, 2006; Scheier & Carver, 1985; Segerstrom, Taylor, Kemeny, & Fahey, 1998).

Stress Management

About 20 percent of Americans report having stress, with 18–33 year-olds reporting the highest levels (American Psychological Association, 2012). Given that the sources of our stress are often difficult to change (e.g., personal finances, current job), a number of interventions have been designed to help reduce the aversive responses to duress. For example, relaxation activities and forms of meditation are techniques that allow individuals to reduce their stress via breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and mental imagery. Physiological arousal from stress can also be reduced via biofeedback, a technique where the individual is shown bodily information that is not normally available to them (e.g., heart rate), and then taught strategies to alter this signal. This type of intervention has even shown promise in reducing heart and hypertension risk, as well as other serious conditions (e.g., Moravec, 2008; Patel, Marmot, & Terry, 1981). But reducing stress does not have to be complicated! For example, exercise is a great stress reduction activity (Salmon, 2001) that has a myriad of health benefits.

The Importance Of Good Health Practices

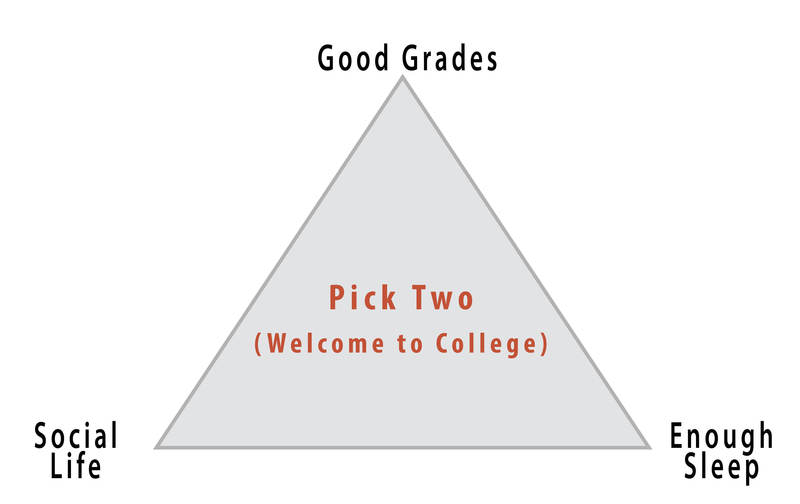

As a student, you probably strive to maintain good grades, to have an active social life, and to stay healthy (e.g., by getting enough sleep), but there is a popular joke about what it’s like to be in college: you can only pick two of these things (see Figure 3 for an example). The busy life of a college student doesn’t always allow you to maintain all three areas of your life, especially during test-taking periods. In one study, researchers found that students taking exams were more stressed and, thus, smoked more, drank more caffeine, had less physical activity, and had worse sleep habits (Oaten & Chang, 2005), all of which could have detrimental effects on their health. Positive health practices are especially important in times of stress when your immune system is compromised due to high stress and the elevated frequency of exposure to the illnesses of your fellow students in lecture halls, cafeterias, and dorms.

Psychologists study both health behaviors and health habits. The former are behaviors that can improve or harm your health. Some examples include regular exercise, flossing, and wearing sunscreen, versus negative behaviors like drunk driving, pulling all-nighters, or smoking. These behaviors become habits when they are firmly established and performed automatically. For example, do you have to think about putting your seatbelt on or do you do it automatically? Habits are often developed early in life thanks to parental encouragement or the influence of our peer group.

While these behaviors sound minor, studies have shown that those who engaged in more of these protective habits (e.g., getting 7–8 hours of sleep regularly, not smoking or drinking excessively, exercising) had fewer illnesses, felt better, and were less likely to die over a 9–12-year follow-up period (Belloc & Breslow 1972; Breslow & Enstrom 1980). For college students, health behaviors can even influence academic performance. For example, poor sleep quality and quantity are related to weaker learning capacity and academic performance (Curcio, Ferrara, & De Gennaro, 2006). Due to the effects that health behaviors can have, much effort is put forward by psychologists to understand how to change unhealthy behaviors, and to understand why individuals fail to act in healthy ways. Health promotion involves enabling individuals to improve health by focusing on behaviors that pose a risk for future illness, as well as spreading knowledge on existing risk factors. These might be genetic risks you are born with, or something you developed over time like obesity, which puts you at risk for Type 2 diabetes and heart disease, among other illnesses.

Psychology And Medicine

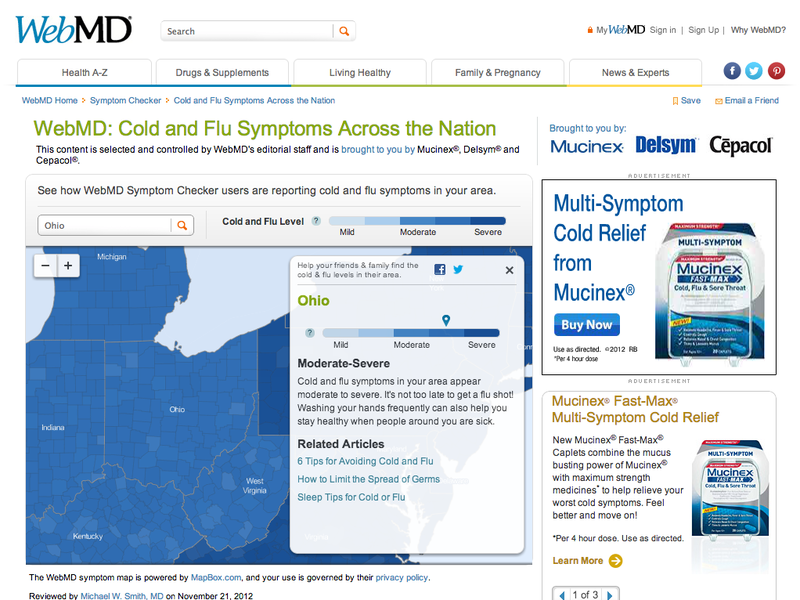

There are many psychological factors that influence medical treatment outcomes. For example, older individuals, (Meara, White, & Cutler, 2004), women (Briscoe, 1987), and those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (Adamson, Ben-Shlomo, Chaturvedi, & Donovan, 2008) are all more likely to seek medical care. On the other hand, some individuals who need care might avoid it due to financial obstacles or preconceived notions about medical practitioners or the illness. Thanks to the growing amount of medical information online, many people now use the Internet for health information and 38% percent report that this influences their decision to see a doctor (Fox & Jones, 2009). Unfortunately, this is not always a good thing because individuals tend to do a poor job assessing the credibility of health information. For example, college-student participants reading online articles about HIV and syphilis rated a physician’s article and a college student’s article as equally credible if the participants said they were familiar with the health topic (Eastin, 2001). Credibility of health information often means how accurate or trustworthy the information is, and it can be influenced by irrelevant factors, such as the website’s design, logos, or the organization’s contact information (Freeman & Spyridakis, 2004). Similarly, many people post health questions on online, unmoderated forums where anyone can respond, which allows for the possibility of inaccurate information being provided for serious medical conditions by unqualified individuals.

After individuals decide to seek care, there is also variability in the information they give their medical provider. Poor communication (e.g., due to embarrassment or feeling rushed) can influence the accuracy of the diagnosis and the effectiveness of the prescribed treatment. Similarly, there is variation following a visit to the doctor. While most individuals are tasked with a health recommendation (e.g., buying and using a medication appropriately, losing weight, going to another expert), not everyone adheres to medical recommendations (Dunbar-Jacob & Mortimer-Stephens, 2010). For example, many individuals take medications inappropriately (e.g., stopping early, not filling prescriptions) or fail to change their behaviors (e.g., quitting smoking). Unfortunately, getting patients to follow medical orders is not as easy as one would think. For example, in one study, over one third of diabetic patients failed to get proper medical care that would prevent or slow down diabetes-related blindness (Schoenfeld, Greene, Wu, & Leske, 2001)! Fortunately, as mobile technology improves, physicians now have the ability to monitor adherence and work to improve it (e.g., with pill bottles that monitor if they are opened at the right time). Even text messages are useful for improving treatment adherence and outcomes in depression, smoking cessation, and weight loss (Cole-Lewis, & Kershaw, 2010).

Being A Health Psychologist

Training as a clinical health psychologist provides a variety of possible career options. Clinical health psychologists often work on teams of physicians, social workers, allied health professionals, and religious leaders. These teams may be formed in locations like rehabilitation centers, hospitals, primary care offices, emergency care centers, or in chronic illness clinics. Work in each of these settings will pose unique challenges in patient care, but the primary responsibility will be the same. Clinical health psychologists will evaluate physical, personal, and environmental factors contributing to illness and preventing improved health. In doing so, they will then help create a treatment strategy that takes into account all dimensions of a person’s life and health, which maximizes its potential for success. Those who specialize in health psychology can also conduct research to discover new health predictors and risk factors, or develop interventions to prevent and treat illness. Researchers studying health psychology work in numerous locations, such as universities, public health departments, hospitals, and private organizations. In the related field of behavioral medicine, careers focus on the application of this type of research. Occupations in this area might include jobs in occupational therapy, rehabilitation, or preventative medicine. Training as a health psychologist provides a wide skill set applicable in a number of different professional settings and career paths.

The Future Of Health Psychology

Much of the past medical research literature provides an incomplete picture of human health. “Health care” is often “illness care.” That is, it focuses on the management of symptoms and illnesses as they arise. As a result, in many developed countries, we are faced with several health epidemics that are difficult and costly to treat. These include obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, to name a few. The National Institutes of Health have called for researchers to use the knowledge we have about risk factors to design effective interventions to reduce the prevalence of preventable illness. Additionally, there are a growing number of individuals across developed countries with multiple chronic illnesses and/or lasting disabilities, especially with older age. Addressing their needs and maintaining their quality of life will require skilled individuals who understand how to properly treat these populations. Health psychologists will be on the forefront of work in these areas.

With this focus on prevention, it is important that health psychologists move beyond studying risk (e.g., depression, stress, hostility, low socioeconomic status) in isolation, and move toward studying factors that confer resilience and protection from disease. There is, fortunately, a growing interest in studying the positive factors that protect our health (e.g., Diener & Chan, 2011; Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Richman, Kubzansky, Maselko, Kawachi, Choo, & Bauer, 2005) with evidence strongly indicating that people with higher positivity live longer, suffer fewer illnesses, and generally feel better. Seligman (2008) has even proposed a field of “Positive Health” to specifically study those who exhibit “above average” health—something we do not think about enough. By shifting some of the research focus to identifying and understanding these health-promoting factors, we may capitalize on this information to improve public health.

Innovative interventions to improve health are already in use and continue to be studied. With recent advances in technology, we are starting to see great strides made to improve health with the aid of computational tools. For example, there are hundreds of simple applications (apps) that use email and text messages to send reminders to take medication, as well as mobile apps that allow us to monitor our exercise levels and food intake (in the growing mobile-health, or m-health, field). These m-health applications can be used to raise health awareness, support treatment and compliance, and remotely collect data on a variety of outcomes. Also exciting are devices that allow us to monitor physiology in real time; for example, to better understand the stressful situations that raise blood pressure or heart rate. With advances like these, health psychologists will be able to serve the population better, learn more about health and health behavior, and develop excellent health-improving strategies that could be specifically targeted to certain populations or individuals. These leaps in equipment development, partnered with growing health psychology knowledge and exciting advances in neuroscience and genetic research, will lead health researchers and practitioners into an exciting new time where, hopefully, we will understand more and more about how to keep people healthy.

Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being

University of Utah, University of Virginia

Subjective well-being (SWB) is the scientific term for happiness and life satisfaction—thinking and feeling that your life is going well, not badly. Scientists rely primarily on self-report surveys to assess the happiness of individuals, but they have validated these scales with other types of measures. People’s levels of subjective well-being are influenced by both internal factors, such as personality and outlook, and external factors, such as the society in which they live. Some of the major determinants of subjective well-being are a person’s inborn temperament, the quality of their social relationships, the societies they live in, and their ability to meet their basic needs. To some degree people adapt to conditions so that over time our circumstances may not influence our happiness as much as one might predict they would. Importantly, researchers have also studied the outcomes of subjective well-being and have found that “happy” people are more likely to be healthier and live longer, to have better social relationships, and to be more productive at work. In other words, people high in subjective well-being seem to be healthier and function more effectively compared to people who are chronically stressed, depressed, or angry. Thus, happiness does not just feel good, but it is good for people and for those around them.

Learning Objectives

- Describe three major forms of happiness and a cause of each of them.

- Be able to list two internal causes of subjective well-being and two external causes of subjective well-being.

- Describe the types of societies that experience the most and least happiness, and why they do.

- Describe the typical course of adaptation to events in terms of the time course of SWB.

- Describe several of the beneficial outcomes of being a happy person.

- Describe how happiness is typically measured.

Introduction

When people describe what they most want out of life, happiness is almost always on the list, and very frequently it is at the top of the list. When people describe what they want in life for their children, they frequently mention health and wealth, occasionally they mention fame or success—but they almost always mention happiness. People will claim that whether their kids are wealthy and work in some prestigious occupation or not, “I just want my kids to be happy.” Happiness appears to be one of the most important goals for people, if not the most important. But what is it, and how do people get it?

In this module I describe “happiness” or subjective well-being (SWB) as a process—it results from certain internal and external causes, and in turn it influences the way people behave, as well as their physiological states. Thus, high SWB is not just a pleasant outcome but is an important factor in our future success. Because scientists have developed valid ways of measuring “happiness,” they have come in the past decades to know much about its causes and consequences.

Types of Happiness

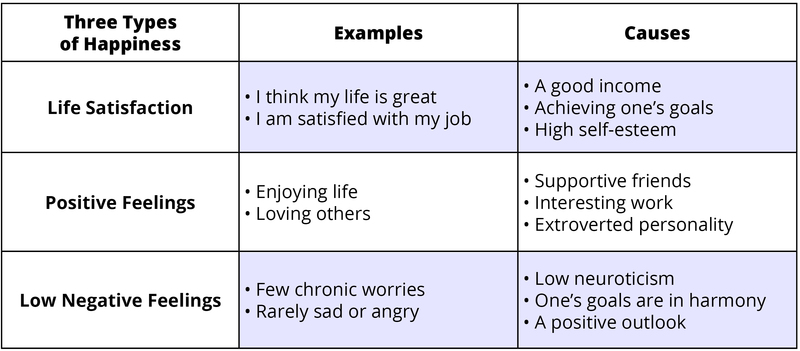

Philosophers debated the nature of happiness for thousands of years, but scientists have recently discovered that happiness means different things. Three major types of happiness are high life satisfaction, frequent positive feelings, and infrequent negative feelings (Diener, 1984). “Subjective well-being” is the label given by scientists to the various forms of happiness taken together. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

You can see in the table that there are different causes of happiness, and that these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. Therefore, there is no single key, no magic wand—high SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). Thus, people who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying.

Some people experience all three elements of happiness—they are very satisfied, enjoy life, and have only a few worries or other unpleasant emotions. Other unfortunate people are missing all three. Most of us also know individuals who have one type of happiness but not another. For example, imagine an elderly person who is completely satisfied with her life—she has done most everything she ever wanted—but is not currently enjoying life that much because of the infirmities of age. There are others who show a different pattern, for example, who really enjoy life but also experience a lot of stress, anger, and worry. And there are those who are having fun, but who are dissatisfied and believe they are wasting their lives. Because there are several components to happiness, each with somewhat different causes, there is no magic single cure-all that creates all forms of SWB. This means that to be happy, individuals must acquire each of the different elements that cause it.

Causes of Subjective Well-Being

There are external influences on people’s happiness—the circumstances in which they live. It is possible for some to be happy living in poverty with ill health, or with a child who has a serious disease, but this is difficult. In contrast, it is easier to be happy if one has supportive family and friends, ample resources to meet one’s needs, and good health. But even here there are exceptions—people who are depressed and unhappy while living in excellent circumstances. Thus, people can be happy or unhappy because of their personalities and the way they think about the world or because of the external circumstances in which they live. People vary in their propensity to happiness—in their personalities and outlook—and this means that knowing their living conditions is not enough to predict happiness.

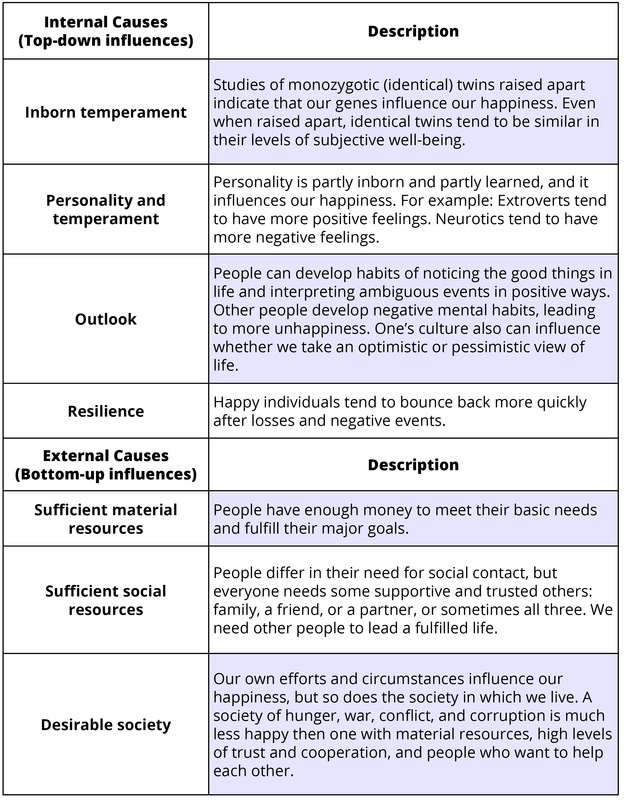

In the table below are shown internal and external circumstances that influence happiness. There are individual differences in what makes people happy, but the causes in the table are important for most people (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lyubomirsky, 2013; Myers, 1992).

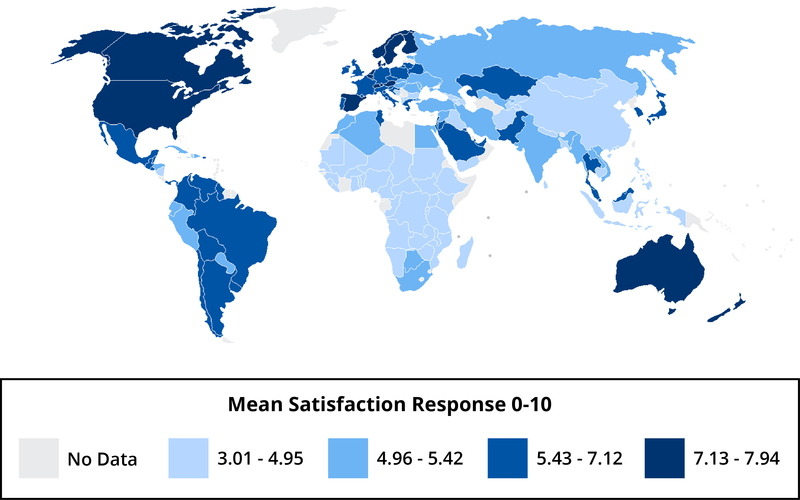

Societal Influences on Happiness

When people consider their own happiness, they tend to think of their relationships, successes and failures, and other personal factors. But a very important influence on how happy people are is the society in which they live. It is easy to forget how important societies and neighborhoods are to people’s happiness or unhappiness. In Figure 1, I present life satisfaction around the world. You can see that some nations, those with the darkest shading on the map, are high in life satisfaction. Others, the lightest shaded areas, are very low. The grey areas in the map are places we could not collect happiness data—they were just too dangerous or inaccessible.

Can you guess what might make some societies happier than others? Much of North America and Europe have relatively high life satisfaction, and much of Africa is low in life satisfaction. For life satisfaction living in an economically developed nation is helpful because when people must struggle to obtain food, shelter, and other basic necessities, they tend to be dissatisfied with lives. However, other factors, such as trusting and being able to count on others, are also crucial to the happiness within nations. Indeed, for enjoying life our relationships with others seem more important than living in a wealthy society. One factor that predicts unhappiness is conflict—individuals in nations with high internal conflict or conflict with neighboring nations tend to experience low SWB.

Money and Happiness

Will money make you happy? A certain level of income is needed to meet our needs, and very poor people are frequently dissatisfied with life (Diener & Seligman, 2004). However, having more and more money has diminishing returns—higher and higher incomes make less and less difference to happiness. Wealthy nations tend to have higher average life satisfaction than poor nations, but the United States has not experienced a rise in life satisfaction over the past decades, even as income has doubled. The goal is to find a level of income that you can live with and earn. Don’t let your aspirations continue to rise so that you always feel poor, no matter how much money you have. Research shows that materialistic people often tend to be less happy, and putting your emphasis on relationships and other areas of life besides just money is a wise strategy. Money can help life satisfaction, but when too many other valuable things are sacrificed to earn a lot of money—such as relationships or taking a less enjoyable job—the pursuit of money can harm happiness.

There are stories of wealthy people who are unhappy and of janitors who are very happy. For instance, a number of extremely wealthy people in South Korea have committed suicide recently, apparently brought down by stress and other negative feelings. On the other hand, there is the hospital janitor who loved her life because she felt that her work in keeping the hospital clean was so important for the patients and nurses. Some millionaires are dissatisfied because they want to be billionaires. Conversely, some people with ordinary incomes are quite happy because they have learned to live within their means and enjoy the less expensive things in life.

It is important to always keep in mind that high materialism seems to lower life satisfaction—valuing money over other things such as relationships can make us dissatisfied. When people think money is more important than everything else, they seem to have a harder time being happy. And unless they make a great deal of money, they are not on average as happy as others. Perhaps in seeking money they sacrifice other important things too much, such as relationships, spirituality, or following their interests. Or it may be that materialists just can never get enough money to fulfill their dreams—they always want more.

To sum up what makes for a happy life, let’s take the example of Monoj, a rickshaw driver in Calcutta. He enjoys life, despite the hardships, and is reasonably satisfied with life. How could he be relatively happy despite his very low income, sometimes even insufficient to buy enough food for his family? The things that make Monoj happy are his family and friends, his religion, and his work, which he finds meaningful. His low income does lower his life satisfaction to some degree, but he finds his children to be very rewarding, and he gets along well with his neighbors. I also suspect that Monoj’s positive temperament and his enjoyment of social relationships help to some degree to overcome his poverty and earn him a place among the happy. However, Monoj would also likely be even more satisfied with life if he had a higher income that allowed more food, better housing, and better medical care for his family.

Besides the internal and external factors that influence happiness, there are psychological influences as well—such as our aspirations, social comparisons, and adaptation. People’s aspirations are what they want in life, including income, occupation, marriage, and so forth. If people’s aspirations are high, they will often strive harder, but there is also a risk of them falling short of their aspirations and being dissatisfied. The goal is to have challenging aspirations but also to be able to adapt to what actually happens in life.

One’s outlook and resilience are also always very important to happiness. Every person will have disappointments in life, fail at times, and have problems. Thus, happiness comes not to people who never have problems—there are no such individuals—but to people who are able to bounce back from failures and adapt to disappointments. This is why happiness is never caused just by what happens to us but always includes our outlook on life.

Adaptation to Circumstances

The process of adaptation is important in understanding happiness. When good and bad events occur, people often react strongly at first, but then their reactions adapt over time and they return to their former levels of happiness. For instance, many people are euphoric when they first marry, but over time they grow accustomed to the marriage and are no longer ecstatic. The marriage becomes commonplace and they return to their former level of happiness. Few of us think this will happen to us, but the truth is that it usually does. Some people will be a bit happier even years after marriage, but nobody carries that initial “high” through the years.

People also adapt over time to bad events. However, people take a long time to adapt to certain negative events such as unemployment. People become unhappy when they lose their work, but over time they recover to some extent. But even after a number of years, unemployed individuals sometimes have lower life satisfaction, indicating that they have not completely habituated to the experience. However, there are strong individual differences in adaptation, too. Some people are resilient and bounce back quickly after a bad event, and others are fragile and do not ever fully adapt to the bad event. Do you adapt quickly to bad events and bounce back, or do you continue to dwell on a bad event and let it keep you down?

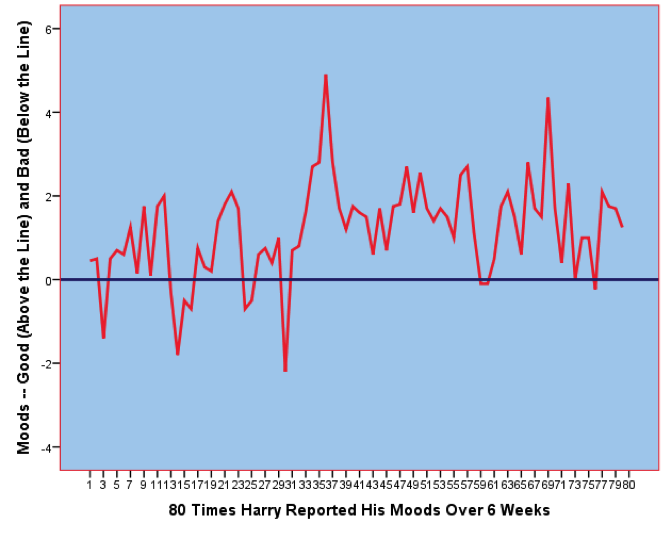

An example of adaptation to circumstances is shown in Figure 3, which shows the daily moods of “Harry,” a college student who had Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a form of cancer). As can be seen, over the 6-week period when I studied Harry’s moods, they went up and down. A few times his moods dropped into the negative zone below the horizontal blue line. Most of the time Harry’s moods were in the positive zone above the line. But about halfway through the study Harry was told that his cancer was in remission—effectively cured—and his moods on that day spiked way up. But notice that he quickly adapted—the effects of the good news wore off, and Harry adapted back toward where he was before. So even the very best news one can imagine—recovering from cancer—was not enough to give Harry a permanent “high.” Notice too, however, that Harry’s moods averaged a bit higher after cancer remission. Thus, the typical pattern is a strong response to the event, and then a dampening of this joy over time. However, even in the long run, the person might be a bit happier or unhappier than before.

Outcomes of High Subjective Well-Being

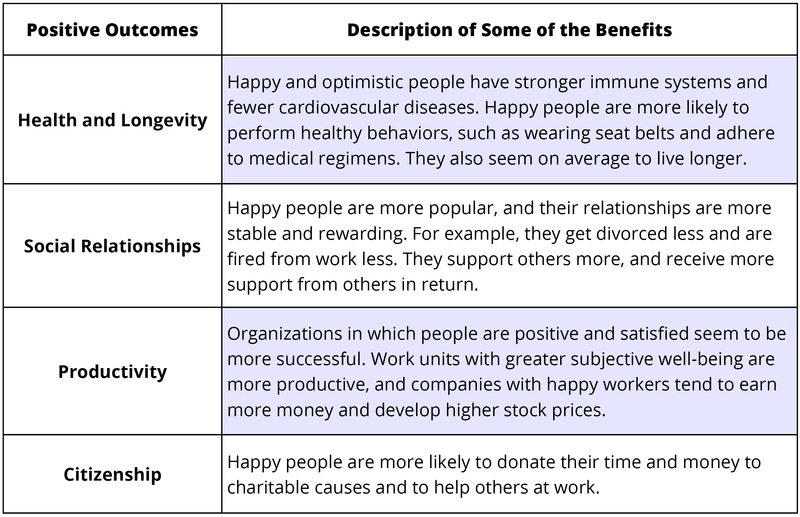

Is the state of happiness truly a good thing? Is happiness simply a feel-good state that leaves us unmotivated and ignorant of the world’s problems? Should people strive to be happy, or are they better off to be grumpy but “realistic”? Some have argued that happiness is actually a bad thing, leaving us superficial and uncaring. Most of the evidence so far suggests that happy people are healthier, more sociable, more productive, and better citizens (Diener & Tay, 2012; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Research shows that the happiest individuals are usually very sociable. The table below summarizes some of the major findings.

Although it is beneficial generally to be happy, this does not mean that people should be constantly euphoric. In fact, it is appropriate and helpful sometimes to be sad or to worry. At times a bit of worry mixed with positive feelings makes people more creative. Most successful people in the workplace seem to be those who are mostly positive but sometimes a bit negative. Thus, people need not be a superstar in happiness to be a superstar in life. What is not helpful is to be chronically unhappy. The important question is whether people are satisfied with how happy they are. If you feel mostly positive and satisfied, and yet occasionally worry and feel stressed, this is probably fine as long as you feel comfortable with this level of happiness. If you are a person who is chronically unhappy much of the time, changes are needed, and perhaps professional intervention would help as well.

Measuring Happiness

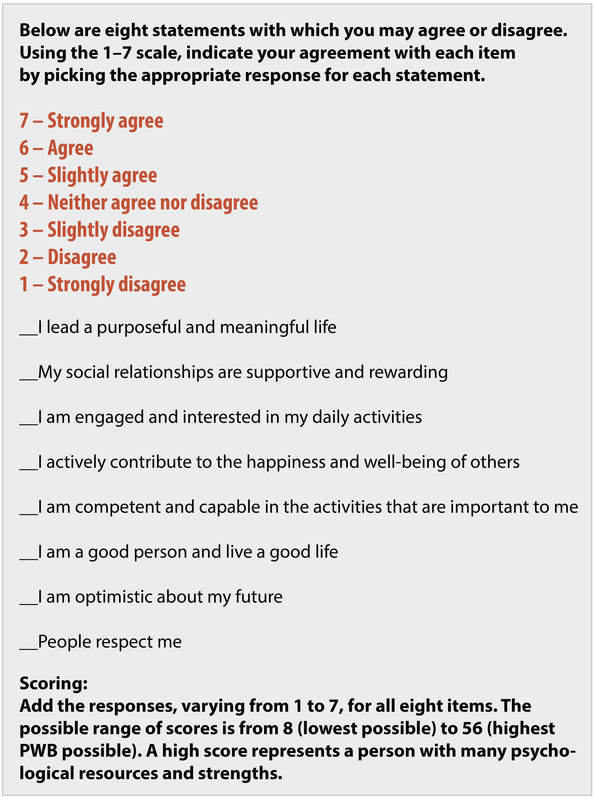

SWB researchers have relied primarily on self-report scales to assess happiness—how people rate their own happiness levels on self-report surveys. People respond to numbered scales to indicate their levels of satisfaction, positive feelings, and lack of negative feelings. You can see where you stand on these scales by going to http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/scales.html or by filling out the Flourishing Scale below. These measures will give you an idea of what popular scales of happiness are like.

The self-report scales have proved to be relatively valid (Diener, Inglehart, & Tay, 2012), although people can lie, or fool themselves, or be influenced by their current moods or situational factors. Because the scales are imperfect, well-being scientists also sometimes use biological measures of happiness (e.g., the strength of a person’s immune system, or measuring various brain areas that are associated with greater happiness). Scientists also use reports by family, coworkers, and friends—these people reporting how happy they believe the target person is. Other measures are used as well to help overcome some of the shortcomings of the self-report scales, but most of the field is based on people telling us how happy they are using numbered scales.

There are scales to measure life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 2008), positive and negative feelings, and whether a person is psychologically flourishing (Diener et al., 2009). Flourishing has to do with whether a person feels meaning in life, has close relationships, and feels a sense of mastery over important life activities. You can take the well-being scales created in the Diener laboratory, and let others take them too, because they are free and open for use.

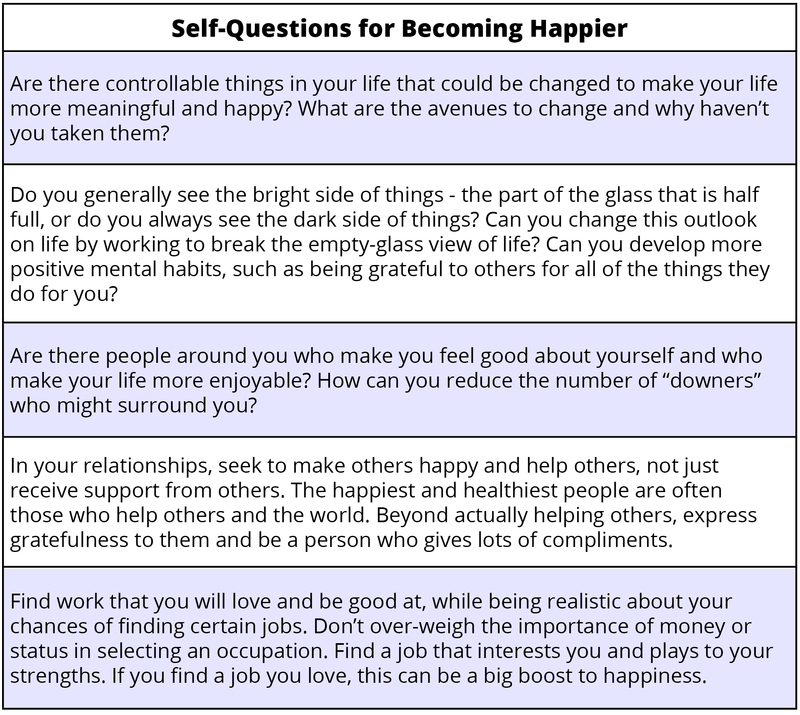

Some Ways to Be Happier

Most people are fairly happy, but many of them also wish they could be a bit more satisfied and enjoy life more. Prescriptions about how to achieve more happiness are often oversimplified because happiness has different components and prescriptions need to be aimed at where each individual needs improvement—one size does not fit all. A person might be strong in one area and deficient in other areas. People with prolonged serious unhappiness might need help from a professional. Thus, recommendations for how to achieve happiness are often appropriate for one person but not for others. With this in mind, I list in Table 4 below some general recommendations for you to be happier (see also Lyubomirsky, 2013):

Outside Resources

- App: 30 iPhone apps to monitor your health

- http://www.hongkiat.com/blog/iphone-health-app/

- Quiz: Hostility

- http://www.mhhe.com/socscience/hhp/fahey7e/wellness_worksheets/wellness_worksheet_090.html

- Self-assessment: Perceived Stress Scale

- http://www.ncsu.edu/assessment/resources/perceived_stress_scale.pdf

- Self-assessment: What’s your real age (based on your health practices and risk factors)?

- http://www.realage.com

- Web: American Psychosomatic Society

- http://www.psychosomatic.org/home/index.cfm

- Web: APA Division 38, Health Psychology

- http://www.health-psych.org

- Web: Society of Behavioral Medicine

- http://www.sbm.org

- Web: Barbara Fredrickson’s website on positive emotions

- http://www.unc.edu/peplab/news.html

- Web: Ed Diener’s website

- http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/

- Web: International Positive Psychology Association

- http://www.ippanetwork.org/

- Web: Positive Acorn Positive Psychology website

- http://positiveacorn.com/

- Web: Sonja Lyubomirsky’s website on happiness

- http://sonjalyubomirsky.com/

- Web: University of Pennsylvania Positive Psychology Center website

- http://www.ppc.sas.upenn.edu/

- Web: World Database on Happiness

- http://www1.eur.nl/fsw/happiness/

Discussion Questions

- What psychological factors contribute to health?

- Which psychosocial constructs and behaviors might help protect us from the damaging effects of stress?

- What kinds of interventions might help to improve resilience? Who will these interventions help the most?

- How should doctors use research in health psychology when meeting with patients?

- Why do clinical health psychologists play a critical role in improving public health?

- Which do you think is more important, the “top-down” personality influences on happiness or the “bottom-up” situational circumstances that influence it? In other words, discuss whether internal sources such as personality and outlook or external factors such situations, circumstances, and events are more important to happiness. Can you make an argument that both are very important?

- Do you know people who are happy in one way but not in others? People who are high in life satisfaction, for example, but low in enjoying life or high in negative feelings? What should they do to increase their happiness across all three types of subjective well-being?

- Certain sources of happiness have been emphasized in this book, but there are others. Can you think of other important sources of happiness and unhappiness? Do you think religion, for example, is a positive source of happiness for most people? What about age or ethnicity? What about health and physical handicaps? If you were a researcher, what question might you tackle on the influences on happiness?

- Are you satisfied with your level of happiness? If not, are there things you might do to change it? Would you function better if you were happier?

- How much happiness is helpful to make a society thrive? Do people need some worry and sadness in life to help us avoid bad things? When is satisfaction a good thing, and when is some dissatisfaction a good thing?

- How do you think money can help happiness? Interfere with happiness? What level of income will you need to be satisfied?

Vocabulary

- Adherence

- In health, it is the ability of a patient to maintain a health behavior prescribed by a physician. This might include taking medication as prescribed, exercising more, or eating less high-fat food.

- Behavioral medicine

- A field similar to health psychology that integrates psychological factors (e.g., emotion, behavior, cognition, and social factors) in the treatment of disease. This applied field includes clinical areas of study, such as occupational therapy, hypnosis, rehabilitation or medicine, and preventative medicine.

- Biofeedback

- The process by which physiological signals, not normally available to human perception, are transformed into easy-to-understand graphs or numbers. Individuals can then use this information to try to change bodily functioning (e.g., lower blood pressure, reduce muscle tension).

- Biomedical Model of Health

- A reductionist model that posits that ill health is a result of a deviation from normal function, which is explained by the presence of pathogens, injury, or genetic abnormality.

- An approach to studying health and human function that posits the importance of biological, psychological, and social (or environmental) processes.

- Chronic disease

- A health condition that persists over time, typically for periods longer than three months (e.g., HIV, asthma, diabetes).

- Control

- Feeling like you have the power to change your environment or behavior if you need or want to.

- Daily hassles

- Irritations in daily life that are not necessarily traumatic, but that cause difficulties and repeated stress.

- Emotion-focused coping

- Coping strategy aimed at reducing the negative emotions associated with a stressful event.

- General Adaptation Syndrome

- A three-phase model of stress, which includes a mobilization of physiological resources phase, a coping phase, and an exhaustion phase (i.e., when an organism fails to cope with the stress adequately and depletes its resources).

- Health

- According to the World Health Organization, it is a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

- Health behavior

- Any behavior that is related to health—either good or bad.

- Hostility

- An experience or trait with cognitive, behavioral, and emotional components. It often includes cynical thoughts, feelings of emotion, and aggressive behavior.

- Mind–body connection

- The idea that our emotions and thoughts can affect how our body functions.

- Problem-focused coping

- A set of coping strategies aimed at improving or changing stressful situations.

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- A field of study examining the relationship among psychology, brain function, and immune function.

- Psychosomatic medicine

- An interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on how biological, psychological, and social processes contribute to physiological changes in the body and health over time.

- Resilience

- The ability to “bounce back” from negative situations (e.g., illness, stress) to normal functioning or to simply not show poor outcomes in the face of adversity. In some cases, resilience may lead to better functioning following the negative experience (e.g., post-traumatic growth).

- Self-efficacy

- The belief that one can perform adequately in a specific situation.

- The size of your social network, or number of social roles (e.g., son, sister, student, employee, team member).

- The perception or actuality that we have a social network that can help us in times of need and provide us with a variety of useful resources (e.g., advice, love, money).

- Stress

- A pattern of physical and psychological responses in an organism after it perceives a threatening event that disturbs its homeostasis and taxes its abilities to cope with the event.

- Stressor

- An event or stimulus that induces feelings of stress.

- Type A Behavior

- Type A behavior is characterized by impatience, competitiveness, neuroticism, hostility, and anger.

- Type B Behavior

- Type B behavior reflects the absence of Type A characteristics and is represented by less competitive, aggressive, and hostile behavior patterns.

- Adaptation

- The fact that after people first react to good or bad events, sometimes in a strong way, their feelings and reactions tend to dampen down over time and they return toward their original level of subjective well-being.

- “Bottom-up” or external causes of happiness

- Situational factors outside the person that influence his or her subjective well-being, such as good and bad events and circumstances such as health and wealth.

- Happiness

- The popular word for subjective well-being. Scientists sometimes avoid using this term because it can refer to different things, such as feeling good, being satisfied, or even the causes of high subjective well-being.

- Life satisfaction

- A person reflects on their life and judges to what degree it is going well, by whatever standards that person thinks are most important for a good life.

- Negative feelings

- Undesirable and unpleasant feelings that people tend to avoid if they can. Moods and emotions such as depression, anger, and worry are examples.

- Positive feelings

- Desirable and pleasant feelings. Moods and emotions such as enjoyment and love are examples.

- Subjective well-being

- The name that scientists give to happiness—thinking and feeling that our lives are going very well.

- Subjective well-being scales

- Self-report surveys or questionnaires in which participants indicate their levels of subjective well-being, by responding to items with a number that indicates how well off they feel.

- “Top-down” or internal causes of happiness

- The person’s outlook and habitual response tendencies that influence their happiness—for example, their temperament or optimistic outlook on life.

References

- Adamson, J., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Chaturvedi, N., & Donovan, J. (2008). Ethnicity, socio-economic position and gender—do they affect reported health—care seeking behaviour? Social Science & Medicine, 57, 895–904.

- American Psychological Association (2012). Stress in American 2012 [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2012/generations.aspx

- Belloc, N. B., & Breslow, L. (1972). Relationship of physical health status and health practices. Preventive Medicine, 1, 409–421.

- Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1981). The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 139–157.

- Breslow, L., & Enstrom, J. E. (1980). Persistence of health habits and their relationship to mortality. Preventive Medicine, 9, 469–483.

- Briscoe, M. E. (1987). Why do people go to the doctor? Sex differences in the correlates of GP consultation. Social Science & Medicine, 25, 507–513.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

- Cohen, S., & Herbert, T. B. (1996). Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–142.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

- Cohen, S., Alper, C. M., Doyle, W. J., Treanor, J. J., & Turner, R. B. (2006). Positive emotional style predicts resistance to illness after experimental exposure to rhinovirus or influenza A virus. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 809–815.

- Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298, 1685–1687.

- Cohen, S., Tyrrell, D. A., & Smith, A. P. (1991). Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. New England Journal of Medicine, 325, 606–612.

- Cole-Lewis, H., & Kershaw, T. (2010). Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiologic Reviews, 32, 56–69.

- Curcio, G., Ferrara, M., & De Gennaro, L. (2006). Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10, 323–337.

- DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 486–495.

- Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 355–391.

- Dunbar-Jacob, J., & Mortimer-Stephens, M. (2001). Treatment adherence in chronic disease. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(12), S57–S60

- Eastin, M. S. (2001). Credibility assessments of online health information: The effects of source expertise and knowledge of content. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 6.

- Fox, S. & Jones, S. (2009). The social life of health information. Pew Internet and American Life Project, California HealthCare Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/8-The-Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

- Freeman, K. S., & Spyridakis, J. H. (2004). An examination of factors that affect the credibility of online health information. Technical Communication, 51, 239–263.

- Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. (1959). Association of specific overt behaviour pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings. Journal of the American Medical Association, 169, 1286–1296.

- Glass, D. C., & Singer, J. E. (1972). Behavioral aftereffects of unpredictable and uncontrollable aversive events: Although subjects were able to adapt to loud noise and other stressors in laboratory experiments, they clearly demonstrated adverse aftereffects. American Scientist, 60, 457–465.

- Herman-Stabl, M. A., Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1995). Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 649–665.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

- House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545.

- Iribarren, C., Sidney, S., Bild, D. E., Liu, K., Markovitz, J. H., Roseman, J. M., & Matthews, K. (2000). Association of hostility with coronary artery calcification in young adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 2546–2551.

- Kubzansky, L. D., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P., & Kawachi, I. (2001). Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the normative aging study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 910–916.

- Matthews, K. A., Glass, D. C., Rosenman, R. H., & Bortner, R. W. (1977). Competitive drive, pattern A, and coronary heart disease: A further analysis of some data from the Western Collaborative Group Study. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 30, 489–498.

- Meara, E., White, C., & Cutler, D. M. (2004). Trends in medical spending by age, 1963–2000. Health Affairs, 23, 176–183.

- Miller, T. Q., Smith, T. W., Turner, C. W., Guijarro, M. L., & Hallet, A. J. (1996). Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 322–348.

- Moravec, C. S. (2008). Biofeedback therapy in cardiovascular disease: rationale and research overview. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 75, S35–S38.

- Nes, L. S., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2006). Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 235–251.

- Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2005). Academic examination stress impairs self–control. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 254–279.

- O’Leary, A. (1985). Self-efficacy and health. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23, 437–451.

- Patel, C., Marmot, M. G., & Terry, D. J. (1981). Controlled trial of biofeedback-aided behavioural methods in reducing mild hypertension. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.), 282, 2005–2008.

- Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 925–971.

- Pressman, S. D., Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2013). Is the emotion-health connection a “first-world problem”? Psychological Science, 24, 544–549.

- Richman, L. S., Kubzansky, L., Maselko, J., Kawachi, I., Choo, P., & Bauer, M. (2005). Positive emotion and health: Going beyond the negative. Health Psychology, 24, 422–429.

- Rodin, J., & Langer, E. J. (1977). Long-term effects of a control-relevant intervention with the institutionalized aged. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 897–902.

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 598–611.

- Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61.

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

- Schoenfeld, E. R., Greene, J. M., Wu, S. Y., & Leske, M. C. (2001). Patterns of adherence to diabetes vision care guidelines: Baseline findings from the Diabetic Retinopathy Awareness Program. Ophthalmology, 108, 563–571.

- Schulz, R., & Hanusa, B.H. (1978). Long-term effects of control and predictability-enhancing interventions: Findings and ethical issues. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 1194–1202.

- Segerstrom, S. C., Taylor, S. E., Kemeny, M. E., & Fahey, J. L. (1998). Optimism is associated with mood, coping, and immune change in response to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1646–1655.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Positive health. Applied Psychology, 57, 3–18.

- Selye, H. (1946). The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, 6, 117–230.

- Sieber, W. J., Rodin, J., Larson, L., Ortega, S., Cummings, N., Levy, S., … Herberman, R. (1992). Modulation of human natural killer cell activity by exposure to uncontrollable stress. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 6, 141–156.

- Spiegel, D., Kraemer, H., Bloom, J., & Gottheil, E. (1989). Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. The Lancet, 334, 888–891.

- Taylor, S. E. (2012) Health psychology (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429.

- Twisk, J. W., Snel, J., Kemper, H. C., & van Mechelen, W. (1999). Changes in daily hassles and life events and the relationship with coronary heart disease risk factors: A 2-year longitudinal study in 27–29-year-old males and females. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46, 229–240.

- Wallston, B. S., & Wallston, K. A. (1978). Locus of control and health: a review of the literature. Health Education & Behavior, 6, 107–117.

- World Health Organization (2013). Cardiovascular diseases. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html

- World Health Organization. (1946). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth. Malden, MA: Wiley/Blackwell.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

- Diener, E., & Tay, L. (2012). The remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. Report of the Well-Being Working Group, Royal Government of Bhutan. Report to the United Nations General Assembly: Well-Being and Happiness: A New Development Paradigm.

- Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2012). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, in press.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). The myths of happiness: What should make you happy, but doesn’t, what shouldn’t make you happy, but does. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

- Myers, D. G. (1992). The pursuit of happiness: Discovering pathways to fulfillment, well-being, and enduring personal joy. New York, NY: Avon.

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.

Authors

Emily Hooker

Emily HookerEmily Hooker is a graduate student in Psychology and Social Behavior at the University of California, Irvine. Hooker is a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow and Golden Key Scholar. Her work explores the role of social relationships in stress processes and health outcomes.

Sarah Pressman

Sarah PressmanSarah Pressman is an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine in the Department of Psychology and Social Behavior. Dr. Pressman’s research focuses on the complex interconnections between positive psychosocial factors and health, with a focus on the physiological and behavioral underpinnings of this link.

Edward Diener

Edward DienerEd Diener, Senior Scientist for the Gallup Organization and professor at the University of Virginia and University of Utah, received three of the highest honors in psychology (APA’s Distinguished Scientist Award, the APS William James Award, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences) for his groundbreaking research on happiness.

Creative Commons License

Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being by Edward Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being by Edward Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Creative Commons License

The Healthy Life by Emily Hooker and Sarah Pressman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

The Healthy Life by Emily Hooker and Sarah Pressman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.