Contents

- 1 Consciousness

- 2 Conscious Experiences

- 3 Conscious Experiences of Visual Perception

- 4 Conscious Experiences of Memory

- 5 Conscious Experiences of Body Awareness

- 6 Conscious Experiences of Decision Making

- 7 Understanding Consciousness

- 8 States of Consciousness

- 9 Introduction

- 10 Levels of Awareness

- 11 Other States of Consciousness

- 12 Conclusion

Consciousness

By Ken Paller and Satoru Suzuki

Northwestern University

Consciousness is the ultimate mystery. What is it and why do we have it? These questions are difficult to answer, even though consciousness is so fundamental to our existence. Perhaps the natural world could exist largely as it is without human consciousness; but taking away consciousness would essentially take away our humanity. Psychological science has addressed questions about consciousness in part by distinguishing neurocognitive functions allied with conscious experience from those that transpire without conscious experience. The continuing investigation of these sorts of distinctions is yielding an empirical basis for new hypotheses about the precursors of conscious experience. Richer conceptualizations are thus being built, combining first-person and third-person perspectives to provide new clues to the mystery of consciousness

Learning Objectives

- Understand scientific approaches to comprehending consciousness.

- Be familiar with evidence about human vision, memory, body awareness, and decision making relevant to the study of consciousness.

- Appreciate some contemporary theories about consciousness.

Conscious Experiences

Contemplate the unique experience of being you at this moment! You, and only you, have direct knowledge of your own conscious experiences. At the same time, you cannot know consciousness from anyone else’s inside view. How can we begin to understand this fantastic ability to have private, conscious experiences?

In a sense, everything you know is from your own vantage point, with your own consciousness at the center. Yet the scientific study of consciousness confronts the challenge of producing general understanding that goes beyond what can be known from one individual’s perspective.

To delve into this topic, some terminology must first be considered. The term consciousness can denote the ability of a person to generate a series of conscious experiences one after another. Here we include experiences of feeling and understanding sensory input, of a temporal sequence of autobiographical events, of imagination, of emotions and moods, of ideas, of memories—the whole range of mental contents open to an individual.

Consciousness can also refer to the state of an individual, as in a sharp or dull state of consciousness, a drug-induced state such as euphoria, or a diminished state due to drowsiness, sleep, neurological abnormality, or coma. In this module, we focus not on states of consciousness or on self-consciousness, but rather on the process that unfolds in the course of a conscious experience—a moment of awareness—the essential ingredient of consciousness.

Other Minds

You have probably experienced the sense of knowing exactly what a friend is thinking. Various signs can guide our inferences about consciousness in others. We can try to infer what’s going on in someone else’s mind by relying on the assumption that they feel what we imagine we would feel in the same situation. We might account for someone’s actions or emotional expressions through our knowledge of that individual and our careful observations of their behavior. In this way, we often display substantial insight into what they are thinking. Other times we are completely wrong.

By measuring brain activity using various neuroscientific technologies, we can acquire additional information useful for deciphering another person’s state of mind. In special circumstances such inferences can be highly accurate, but limitations on mind reading remain, highlighting the difficulty of understanding exactly how conscious experiences arise.

A Science of Consciousness

Attempts to understand consciousness have been pervasive throughout human history, mostly dominated by philosophical analyses focused on the first-person perspective. Now we have a wider set of approaches that includes philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, cognitive science, and contemplative science (Blackmore, 2006; Koch, 2012; Zelazo, Moscovitch, & Thompson, 2007; Zeman, 2002).

The challenge for this combination of approaches is to give a comprehensive explanation of consciousness. That explanation would include describing the benefits of consciousness, particularly for behavioral capabilities that conscious experiences allow, that trump automatic behaviors. Subjective experiences also need to be described in a way that logically shows how they result from precursor events in the human brain. Moreover, a full account would describe how consciousness depends on biological, environmental, social, cultural, and developmental factors.

At the outset, a central question is how to conceive of consciousness relative to other things we know. Objects in our environment have a physical basis and are understood to be composed of constituents, such that they can be broken down into molecules, elements, atoms, particles, and so on. Yet we can also understand things relationally and conceptually. Sometimes a phenomenon can best be conceived as a process rather than a physical entity (e.g., digestion is a process whereby food is broken down). What, then, is the relationship between our conscious thoughts and the physical universe, and in particular, our brains?

Rene Descartes’ position, dualism, was that mental and physical are, in essence, different substances. This view can be contrasted with reductionist views that mental phenomena can be explained via descriptions of physical phenomena. Although the dualism/reductionism debate continues, there are many ways in which mind can be shown to depend on brain.

A prominent orientation to the scientific study of consciousness is to seek understanding of these dependencies—to see how much light they can shed on consciousness. Significant advances in our knowledge about consciousness have thus been gained, as seen in the following examples.

Conscious Experiences of Visual Perception

Suppose you meet your friend at a crowded train station. You may notice a subtle smile on her face. At that moment you are probably unaware of many other things happening within your view. What makes you aware of some things but not others? You probably have your own intuitions about this, but experiments have proven wrong many common intuitions about what generates visual awareness.

For instance, you may think that if you attentively look at a bright spot, you must be aware of it. Not so. In a phenomenon known as motion-induced blindness, bright discs completely vanish from your awareness in full attention. To experience this for yourself, see this module’s Outside Resource section for a demonstration of motion-induced blindness.

You may think that if you deeply analyze an image, decoding its meaning and making a decision about it, you must be aware of the image. Not necessarily. When a number is briefly flashed and rapidly replaced by a random pattern, you may have no awareness of it, despite the fact that your brain allows you to determine that the number is greater than 5, and then prepare your right hand for a key press if that is what you were instructed to do (Dehaene et al., 1998).

Thus, neither the brightness of an image, paying full attention to it, nor deeply analyzing it guarantees that you will be aware of it. What, then, is the crucial ingredient of visual awareness?

A contemporary answer is that our awareness of a visual feature depends on a certain type of reciprocal exchange of information across multiple brain areas, particularly in the cerebral cortex. In support of this idea, directly activating your visual motion area (known as V5) with an externally applied magnetic field (transcranial magnetic stimulation) will make you see moving dots. This is not surprising. What is surprising is that activating your visual motion area alone does not let you see motion. You will not see moving dots if the feedback signal from V5 to the primary visual cortex is disrupted by a further transcranial magnetic stimulation pulse (Pascual-Leone & Walsh, 2001). The reverberating reciprocal exchange of information between higher-level visual areas and primary visual cortex appears to be essential for generating visual awareness.

This idea can also explain why people with certain types of brain damage lack visual awareness. Consider a patient with brain damage limited to primary visual cortex who claims not to see anything — a problem termedcortical blindness. Other areas of visual cortex may still receive visual input through projections from brain structures such as the thalamus and superior colliculus, and these networks may mediate some preserved visual abilities that take place without awareness. For example, a patient with cortical blindness might detect moving stimuli via V5 activation but still have no conscious experiences of the stimuli, because the reverberating reciprocal exchange of information cannot take place between V5 and the damaged primary visual cortex. The preserved ability to detect motion might be evident only when a guess is required (“guess whether something moved to the left or right”)—otherwise the answer would be “I didn’t see anything.” This phenomenon of blindsight refers to blindness due to a neurological cause that preserves abilities to analyze and respond to visual stimuli that are not consciously experienced (Lamme, 2001).

If exchanges of information across brain areas are crucial for generating visual awareness, neural synchronization must play an important role because it promotes neural communication. A neuron’s excitability varies over time. Communication among neural populations is enhanced when their oscillatory cycles of excitability are synchronized. In this way, information transmitted from one population in its excitable phase is received by the target population when it is also in its excitable phase. Indeed, oscillatory neural synchronization in the beta- and gamma-band frequencies (identified according to the number of oscillations per second, 13–30 Hz and 30–100 Hz, respectively) appears to be closely associated with visual awareness. This idea is highlighted in the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory of Consciousness (Dehaene & Changeux, 2011), in which sharing of information among prefrontal, inferior parietal, and occipital regions of the cerebral cortex is postulated to be especially important for generating awareness.

A related view, the Information Integration Theory of Consciousness, is that shared information itself constitutes consciousness (Tononi, 2004). An organism would have minimal consciousness if the structure of shared information is simple, whereas it would have rich conscious experiences if the structure of shared information is complex. Roughly speaking, complexity is defined as the number of intricately interrelated informational units or ideas generated by a web of local and global sharing of information. The degree of consciousness in an organism (or a machine) would be high if numerous and diversely interrelated ideas arise, low if only a few ideas arise or if there are numerous ideas but they are random and unassociated. Computational analyses provide additional perspectives on such proposals. In particular, if every neuron is connected to every other neuron, all neurons would tend to activate together, generating few distinctive ideas. With a very low level of neuronal connectivity at the other extreme, all neurons would tend to activate independently, generating numerous but unassociated ideas. To promote a rich level of consciousness, then, a suitable mixture of short-, medium-, and long-range neural connections would be needed. The human cerebral cortex may indeed have such an optimum structure of neural connectivity. Given how consciousness is conceptualized in this theory as graded rather than all-or-none, a quantitative approach (e.g., Casali et al., 2013; Monti et al., 2013) could conceivably be used to estimate the level of consciousness in nonhuman species and artificial beings.

Conscious Experiences of Memory

The pinnacle of conscious human memory functions is known as episodic recollection because it allows one to reexperience the past, to virtually relive an earlier event. People who suffer from amnesia due to neurological damage to certain critical brain areas have poor memory for events and facts. Their memory deficit disrupts the type of memory termed declarative memory and makes it difficult to consciously remember. However, amnesic insults typically spare a set of memory functions that do not involve conscious remembering. These other types of memory, which include various habits, motor skills, cognitive skills, and procedures, can be demonstrated when an individual executes various actions as a function of prior learning, but in these cases a conscious experience of remembering is not necessarily included.

Research on amnesia has thus supported the proposal that conscious remembering requires a specific set of brain operations that depend on networks of neurons in the cerebral cortex. Some of the other types of memory involve only subcortical brain regions, but there are also notable exceptions. In particular, perceptual priming is a type of memory that does not entail the conscious experience of remembering and that is typically preserved in amnesia. Perceptual priming is thought to reflect a fluency of processing produced by a prior experience, even when the individual cannot remember that prior experience. For example, a word or face might be perceived more efficiently if it had been viewed minutes earlier than if it hadn’t. Whereas a person with amnesia can demonstrate this item-specific fluency due to changes in corresponding cortical areas, they nevertheless would be impaired if asked to recognize the words or faces they previously experienced. A reasonable conclusion on the basis of this evidence is that remembering an episode is a conscious experience not merely due to the involvement of one portion of the cerebral cortex, but rather due to the specific configuration of cortical activity involved in the sharing or integration of information.

Further neuroscientific studies of memory retrieval have shed additional light on the necessary steps for conscious recollection. For example, storing memories for the events we experience each day appears to depend on connections among multiple cortical regions as well as on a brain structure known as the hippocampus. Memory storage becomes more secure due to interactions between the hippocampus and cerebral cortex that can transpire over extended time periods following the initial registration of information. Conscious retrieval thus depends on the activity of elaborate sets of networks in the cortex. Memory retrieval that does not include conscious recollection depends either on restricted portions of the cortex or on brain regions separate from the cortex.

The ways in which memory expressions that include the awareness of remembering differ from those that do not thus highlight the special nature of conscious memory experiences (Paller, Voss, & Westerberg, 2009; Voss, Lucas, & Paller, 2012). Indeed, memory storage in the brain can be very complex for many different types of memory, but there are specific physiological prerequisites for the type of memory that coincides with conscious recollection.

Conscious Experiences of Body Awareness

The brain can generate body awareness by registering coincident sensations. For example, when you rub your arm, you see your hand rubbing your arm and simultaneously feel the rubbing sensation in both your hand and your arm. This simultaneity tells you that it is your hand and your arm. Infants use the same type of coincident sensations to initially develop the self/nonself distinction that is fundamental to our construal of the world.

The fact that your brain constructs body awareness in this way can be experienced via the rubber-hand illusion (see Outside Resource on this). If you see a rubber hand being rubbed and simultaneously feel the corresponding rubbing sensation on your own body out of view, you will momentarily feel a bizarre sensation—that the rubber hand is your own.

The construction of our body awareness appears to be mediated by specific brain mechanisms involving a region of the cortex known as the temporoparietal junction. Damage to this brain region can generate distorted body awareness, such as feeling a substantially elongated torso. Altered neural activity in this region through artificial stimulation can also produce an out-of-body experience (see this module’s Outside Resources section), in which you feel like your body is in another location and you have a novel perspective on your body and the world, such as from the ceiling of the room.

Remarkably, comparable brain mechanisms may also generate the normal awareness of the sense of self and the sensation of being inside a body. In the context of virtual reality this sensation is known as presence (the compelling experience of actually being there). Our normal localization of the self may be equally artificial, in that it is not a given aspect of life but is constructed through a special brain mechanism.

A Social Neuroscience Theory of Consciousness (Graziano & Kastner, 2011) ascribes an important role to our ability to localize our own sense of self. The main premise of the theory is that you fare better in a social environment to the extent that you can predict what people are going to do. So, the human brain has developed mechanisms to construct models of other people’s attention and intention, and to localize those models in the corresponding people’s heads to keep track of them. The proposal is that the same brain mechanism was adapted to construct a model of one’s own attention and intention, which is then localized in one’s own head and perceived as consciousness. If so, then the primary function of consciousness is to allow us to predict our own behavior. Research is needed to test the major predictions of this new theory, such as whether changes in consciousness (e.g., due to normal fluctuations, psychiatric disease, brain damage) are closely associated with changes in the brain mechanisms that allow us to model other people’s attention and intention.

Conscious Experiences of Decision Making

Choosing among multiple possible actions, the sense of volition, is closely associated with our subjective feeling of consciousness. When we make a lot of decisions, we may feel especially conscious and then feel exhausted, as if our mental energy has been drained.

We make decisions in two distinct ways. Sometimes we carefully analyze and weigh different factors to reach a decision, taking full advantage of the brain’s conscious mode of information processing. Other times we make a gut decision, trusting the unconscious mode of information processing (although it still depends on the brain). The unconscious mode is adept at simultaneously considering numerous factors in parallel, which can yield an overall impression of the sum total of evidence. In this case, we have no awareness of the individual considerations. In the conscious mode, in contrast, we can carefully scrutinize each factor—although the act of focusing on a specific factor can interfere with weighing in other factors.

One might try to optimize decision making by taking into account these two strategies. A careful conscious decision should be effective when there are only a few known factors to consider. A gut decision should be effective when a large number of factors should be considered simultaneously. Gut decisions can indeed be accurate on occasion (e.g., guessing which of many teams will win a close competition), but only if you are well versed in the relevant domain (Dane, Rockmann, & Pratt, 2012).

As we learn from our experiences, some of this gradual knowledge accrual is unconscious; we don’t know we have it and we can use it without knowing it. On the other hand, consciously acquired information can be uniquely beneficial by allowing additional stages of control (de Lange, van Gaal, Lamme, & Dehaene, 2011). It is often helpful to control which new knowledge we acquire and which stored information we retrieve in accordance with our conscious goals and beliefs.

Whether you choose to trust your gut or to carefully analyze the relevant factors, you feel that you freely reach your own decision. Is this feeling of free choice real? Contemporary experimental techniques fall short of answering this existential question. However, it is likely that at least the sense of immediacy of our decisions is an illusion.

In one experiment, people were asked to freely consider whether to press the right button or the left button, and to press it when they made the decision (Soon, Brass, Heinze, & Haynes, 2008). Although they indicated that they made the decision immediately before pressing the button, their brain activity, measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging, predicted their decision as much as 10 seconds before they said they freely made the decision. In the same way, each conscious experience is likely preceded by precursor brain events that on their own do not entail consciousness but that culminate in a conscious experience.

In many situations, people generate a reason for an action that has nothing to do with the actual basis of the decision to act in a particular way. We all have a propensity to retrospectively produce a reasonable explanation for our behavior, yet our behavior is often the result of unconscious mental processing, not conscious volition.

Why do we feel that each of our actions is immediately preceded by our own decision to act? This illusion may help us distinguish our own actions from those of other agents. For example, while walking hand-in-hand with a friend, if you felt you made a decision to turn left immediately before you both turned left, then you know that you initiated the turn; otherwise, you would know that your friend did.

Even if some aspects of the decision-making process are illusory, to what extent are our decisions determined by prior conditions? It certainly seems that we can have full control of some decisions, such as when we create a conscious intention that leads to a specific action: You can decide to go left or go right. To evaluate such impressions, further research must develop a better understanding of the neurocognitive basis of volition, which is a tricky undertaking, given that decisions are conceivably influenced by unconscious processing, neural noise, and the unpredictability of a vast interactive network of neurons in the brain.

Yet belief in free choice has been shown to promote moral behavior, and it is the basis of human notions of justice. The sense of free choice may be a beneficial trait that became prevalent because it helped us flourish as social beings.

Understanding Consciousness

Our human consciousness unavoidably colors all of our observations and our attempts to gain understanding. Nonetheless, scientific inquiries have provided useful perspectives on consciousness. The advances described above should engender optimism about the various research strategies applied to date and about the prospects for further insight into consciousness in the future.

Because conscious experiences are inherently private, they have sometimes been taken to be outside the realm of scientific inquiry. This view idealizes science as an endeavor involving only observations that can be verified by multiple observers, relying entirely on the third-person perspective, or the view from nowhere (from no particular perspective). Yet conducting science is a human activity that depends, like other human activities, on individuals and their subjective experiences. A rational scientific account of the world cannot avoid the fact that people have subjective experiences.

Subjectivity thus has a place in science. Conscious experiences can be subjected to systematic analysis and empirical tests to yield progressive understanding. Many further questions remain to be addressed by scientists of the future. Is the first-person perspective of a conscious experience basically the same for all human beings, or do individuals differ fundamentally in their introspective experiences and capabilities? Should psychological science focus only on ordinary experiences of consciousness, or are extraordinary experiences also relevant? Can training in introspection lead to a specific sort of expertise with respect to conscious experience? An individual with training, such as through extensive meditation practice, might be able to describe their experiences in a more precise manner, which could then support improved characterizations of consciousness. Such a person might be able to understand subtleties of experience that other individuals fail to notice, and thereby move our understanding of consciousness significantly forward. These and other possibilities await future scientific inquiries into consciousness.

States of Consciousness

By Robert Biswas-Diener and Jake Teeny

Portland State University, The Ohio State University

No matter what you’re doing–solving homework, playing a video game, simply picking out a shirt–all of your actions and decisions relate to your consciousness. But as frequently as we use it, have you ever stopped to ask yourself: What really is consciousness? In this module, we discuss the different levels of consciousness and how they can affect your behavior in a variety of situations. As well, we explore the role of consciousness in other, “altered” states like hypnosis and sleep.

Learning Objectives

- Define consciousness and distinguish between high and low conscious states

- Explain the relationship between consciousness and bias

- Understand the difference between popular portrayals of hypnosis and how it is currently used therapeutically

Introduction

Have you ever had a fellow motorist stopped beside you at a red light, singing his brains out, or picking his nose, or otherwise behaving in ways he might not normally do in public? There is something about being alone in a car that encourages people to zone out and forget that others can see them. Although these little lapses of attention are amusing for the rest of us, they are also instructive when it comes to the topic of consciousness.

Consciousness is a term meant to indicate awareness. It includes awareness of the self, of bodily sensations, of thoughts and of the environment. In English, we use the opposite word “unconscious” to indicate senselessness or a barrier to awareness, as in the case of “Theresa fell off the ladder and hit her head, knocking herself unconscious.” And yet, psychological theory and research suggest that consciousness and unconsciousness are more complicated than falling off a ladder. That is, consciousness is more than just being “on” or “off.” For instance, Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)—a psychological theorist—understood that even while we are awake, many things lay outside the realm of our conscious awareness (like being in the car and forgetting the rest of the world can see into your windows). In response to this notion, Freud introduced the concept of the “subconscious” (Freud, 2001) and proposed that some of our memories and even our basic motivations are not always accessible to our conscious minds.

Upon reflection, it is easy to see how slippery a topic consciousness is. For example, are people conscious when they are daydreaming? What about when they are drunk? In this module, we will describe several levels of consciousness and then discuss altered states of consciousness such as hypnosis and sleep.

Levels of Awareness

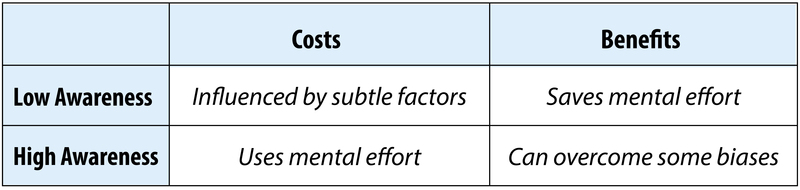

In 1957, a marketing researcher inserted the words “Eat Popcorn” onto one frame of a film being shown all across the United States. And although that frame was only projected onto the movie screen for 1/24th of a second—a speed too fast to be perceived by conscious awareness—the researcher reported an increase in popcorn sales by nearly 60%. Almost immediately, all forms of “subliminal messaging” were regulated in the US and banned in countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom. Even though it was later shown that the researcher had made up the data (he hadn’t even inserted the words into the film), this fear about influences on our subconscious persists. At its heart, this issue pits various levels of awareness against one another. On the one hand, we have the “low awareness” of subtle, even subliminal influences. On the other hand, there is you—the conscious thinking, feeling you which includes all that you are currently aware of, even reading this sentence. However, when we consider these different levels of awareness separately, we can better understand how they operate.

Low Awareness

You are constantly receiving and evaluating sensory information. Although each moment has too many sights, smells, and sounds for them all to be consciously considered, our brains are nonetheless processing all that information. For example, have you ever been at a party, overwhelmed by all the people and conversation, when out of nowhere you hear your name called? Even though you have no idea what else the person is saying, you are somehow conscious of your name (for more on this, “the cocktail party effect,” see Noba’s Module on Attention). So, even though you may not be aware of various stimuli in your environment, your brain is paying closer attention than you think.

Similar to a reflex (like jumping when startled), some cues, or significant sensory information, will automatically elicit a response from us even though we never consciously perceive it. For example, Öhman and Soares (1994) measured subtle variations in sweating of participants with a fear of snakes. The researchers flashed pictures of different objects (e.g., mushrooms, flowers, and most importantly, snakes) on a screen in front of them, but did so at speeds that left the participant clueless as to what he or she had actually seen. However, when snake pictures were flashed, these participants started sweating more (i.e., a sign of fear), even though they had no idea what they’d just viewed!

Although our brains perceive some stimuli without our conscious awareness, do they really affect our subsequent thoughts and behaviors? In a landmark study, Bargh, Chen, and Burrows (1996) had participants solve a word search puzzle where the answers pertained to words about the elderly (e.g., “old,” “grandma”) or something random (e.g., “notebook,” “tomato”). Afterward, the researchers secretly measured how fast the participants walked down the hallway exiting the experiment. And although none of the participants were aware of a theme to the answers, those who had solved a puzzle with elderly words (vs. those with other types of words) walked more slowly down the hallway!

This effect is called priming (i.e., readily “activating” certain concepts and associations from one’s memory) has been found in a number of other studies. For example, priming people by having them drink from a warm glass (vs. a cold one) resulted in behaving more “warmly” toward others (Williams & Bargh, 2008). Although all of these influences occur beneath one’s conscious awareness, they still have a significant effect on one’s subsequent thoughts and behaviors.

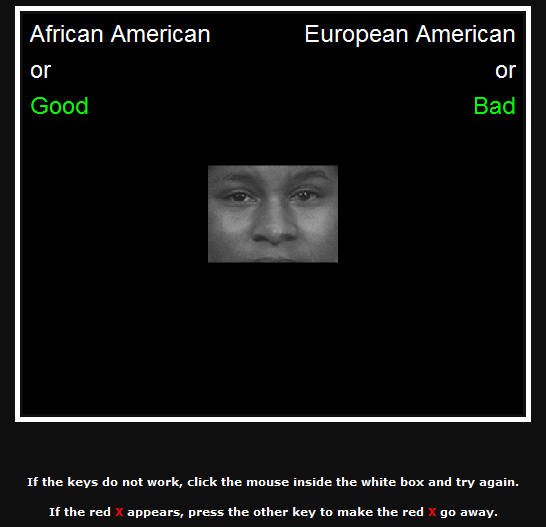

In the last two decades, researchers have made advances in studying aspects of psychology that exist beyond conscious awareness. As you can understand, it is difficult to use self-reports and surveys to ask people about motives or beliefs that they, themselves, might not even be aware of! One way of side-stepping this difficulty can be found in the implicit associations test, or IAT (Greenwald, McGhee & Schwartz, 1998). This research method uses computers to assess people’s reaction times to various stimuli and is a very difficult test to fake because it records automatic reactions that occur in milliseconds. For instance, to shed light on deeply held biases, the IAT might present photographs of Caucasian faces and Asian faces while asking research participants to click buttons indicating either “good” or “bad” as quickly as possible. Even if the participant clicks “good” for every face shown, the IAT can still pick up tiny delays in responding. Delays are associated with more mental effort needed to process information. When information is processed quickly—as in the example of white faces being judged as “good”—it can be contrasted with slower processing—as in the example of Asian faces being judged as “good”—and the difference in processing speed is reflective of bias. In this regard, the IAT has been used for investigating stereotypes (Nosek, Banaji & Greenwald, 2002) as well as self-esteem (Greenwald & Farnam, 2000). This method can help uncover non-conscious biases as well as those that we are motivated to suppress.

High Awareness

Just because we may be influenced by these “invisible” factors, it doesn’t mean we are helplessly controlled by them. The other side of the awareness continuum is known as “high awareness.” This includes effortful attention and careful decision making. For example, when you listen to a funny story on a date, or consider which class schedule would be preferable, or complete a complex math problem, you are engaging a state of consciousness that allows you to be highly aware of and focused on particular details in your environment.

Mindfulness is a state of higher consciousness that includes an awareness of the thoughts passing through one’s head. For example, have you ever snapped at someone in frustration, only to take a moment and reflect on why you responded so aggressively? This more effortful consideration of your thoughts could be described as an expansion of your conscious awareness as you take the time to consider the possible influences on your thoughts. Research has shown that when you engage in this more deliberate consideration, you are less persuaded by irrelevant yet biasing influences, like the presence of a celebrity in an advertisement (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Higher awareness is also associated with recognizing when you’re using a stereotype, rather than fairly evaluating another person (Gilbert & Hixon, 1991).

Humans alternate between low and high thinking states. That is, we shift between focused attention and a less attentive default sate, and we have neural networks for both (Raichle, 2015). Interestingly, the the less we’re paying attention, the more likely we are to be influenced by non-conscious stimuli (Chaiken, 1980). Although these subtle influences may affect us, we can use our higher conscious awareness to protect against external influences. In what’s known as the Flexible Correction Model (Wegener & Petty, 1997), people who are aware that their thoughts or behavior are being influenced by an undue, outside source, can correct their attitude against the bias. For example, you might be aware that you are influenced by mention of specific political parties. If you were motivated to consider a government policy you can take your own biases into account to attempt to consider the policy in a fair way (on its own merits rather than being attached to a certain party).

To help make the relationship between lower and higher consciousness clearer, imagine the brain is like a journey down a river. In low awareness, you simply float on a small rubber raft and let the currents push you. It’s not very difficult to just drift along but you also don’t have total control. Higher states of consciousness are more like traveling in a canoe. In this scenario, you have a paddle and can steer, but it requires more effort. This analogy applies to many states of consciousness, but not all. What about other states such as like sleeping, daydreaming, or hypnosis? How are these related to our conscious awareness?

Other States of Consciousness

Hypnosis

If you’ve ever watched a stage hypnotist perform, it may paint a misleading portrait of this state of consciousness. The hypnotized people on stage, for example, appear to be in a state similar to sleep. However, as the hypnotist continues with the show, you would recognize some profound differences between sleep and hypnosis. Namely, when you’re asleep, hearing the word “strawberry” doesn’t make you flap your arms like a chicken. In stage performances, the hypnotized participants appear to be highly suggestible, to the point that they are seemingly under the hypnotist’s control. Such performances are entertaining but have a way of sensationalizing the true nature of hypnotic states.

Hypnosis is an actual, documented phenomenon—one that has been studied and debated for over 200 years (Pekala et al., 2010). Franz Mesmer (1734 – 1815) is often credited as among the first people to “discover” hypnosis, which he used to treat members of elite society who were experiencing psychological distress. It is from Mesmer’s name that we get the English word, “mesmerize” meaning “to entrance or transfix a person’s attention.” Mesmer attributed the effect of hypnosis to “animal magnetism,” a supposed universal force (similar to gravity) that operates through all human bodies. Even at the time, such an account of hypnosis was not scientifically supported, and Mesmer himself was frequently the center of controversy.

Over the years, researchers have proposed that hypnosis is a mental state characterized by reduced peripheral awareness and increased focus on a singular stimulus, which results in an enhanced susceptibility to suggestion (Kihlstrom, 2003). For example, the hypnotist will usually induce hypnosis by getting the person to pay attention only to the hypnotist’s voice. As the individual focuses more and more on that, s/he begins to forget the context of the setting and responds to the hypnotist’s suggestions as if they were his or her own. Some people are naturally more suggestible, and therefore more “hypnotizable” than are others, and this is especially true for those who score high in empathy (Wickramasekera II & Szlyk, 2003). One common “trick” of stage hypnotists is to discard volunteers who are less suggestible than others.

Dissociation is the separation of one’s awareness from everything besides what one is centrally focused on. For example, if you’ve ever been daydreaming in class, you were likely so caught up in the fantasy that you didn’t hear a word the teacher said. During hypnosis, this dissociation becomes even more extreme. That is, a person concentrates so much on the words of the hypnotist that s/he loses perspective of the rest of the world around them. As a consequence of dissociation, a person is less effortful, and less self-conscious in consideration of his or her own thoughts and behaviors. Similar to low awareness states, where one often acts on the first thought that comes to mind, so, too, in hypnosis does the individual simply follow the first thought that comes to mind, i.e., the hypnotist’s suggestion. Still, just because one is more susceptible to suggestion under hypnosis, it doesn’t mean s/he will do anything that’s ordered. To be hypnotized, you must first want to be hypnotized (i.e., you can’t be hypnotized against your will; Lynn & Kirsh, 2006), and once you are hypnotized, you won’t do anything you wouldn’t also do while in a more natural state of consciousness (Lynn, Rhue, & Weekes, 1990).

Today, hypnotherapy is still used in a variety of formats, and it has evolved from Mesmer’s early tinkering with the concept. Modern hypnotherapy often uses a combination of relaxation, suggestion, motivation and expectancies to create a desired mental or behavioral state. Although there is mixed evidence on whether hypnotherapy can help with addiction reduction (e.g., quitting smoking; Abbot et al., 1998) there is some evidence that it can be successful in treating sufferers of acute and chronic pain (Ewin, 1978; Syrjala et al., 1992). For example, one study examined the treatment of burn patients with either hypnotherapy, pseudo-hypnosis (i.e., a placebo condition), or no treatment at all. Afterward, even though people in the placebo condition experienced a 16% decrease in pain, those in the actual hypnosis condition experienced a reduction of nearly 50% (Patterson et al., 1996). Thus, even though hypnosis may be sensationalized for television and movies, its ability to disassociate a person from their environment (or their pain) in conjunction with increased suggestibility to a clinician’s recommendations (e.g., “you will feel less anxiety about your chronic pain”) is a documented practice with actual medical benefits.

Now, similar to hypnotic states, trance states also involve a dissociation of the self; however, people in a trance state are said to have less voluntary control over their behaviors and actions. Trance states often occur in religious ceremonies, where the person believes he or she is “possessed” by an otherworldly being or force. While in trance, people report anecdotal accounts of a “higher consciousness” or communion with a greater power. However, the body of research investigating this phenomenon tends to reject the claim that these experiences constitute an “altered state of consciousness.”

Most researchers today describe both hypnosis and trance states as “subjective” alterations of consciousness, not an actually distinct or evolved form (Kirsch & Lynn, 1995). Just like you feel different when you’re in a state of deep relaxation, so, too, are hypnotic and trance states simply shifts from the standard conscious experience. Researchers contend that even though both hypnotic and trance states appear and feel wildly different than the normal human experience, they can be explained by standard socio-cognitive factors like imagination, expectation, and the interpretation of the situation.

Sleep

You may have experienced the sensation– as you are falling asleep– of falling and then found yourself physically jerking forward and grabbing out as if you were really falling. Sleep is a unique state of consciousness; it lacks full awareness but the brain is still active. People generally follow a “biological clock” that impacts when they naturally become drowsy, when they fall asleep, and the time they naturally awaken. The hormone melatonin increases at night and is associated with becoming sleepy. Your natural daily rhythm, or Circadian Rhythm, can be influenced by the amount of daylight to which you are exposed as well as your work and activity schedule. Changing your location, such as flying from Canada to England, can disrupt your natural sleep rhythms, and we call this jet lag. You can overcome jet lag by synchronizing yourself to the local schedule by exposing yourself to daylight and forcing yourself to stay awake even though you are naturally sleepy.

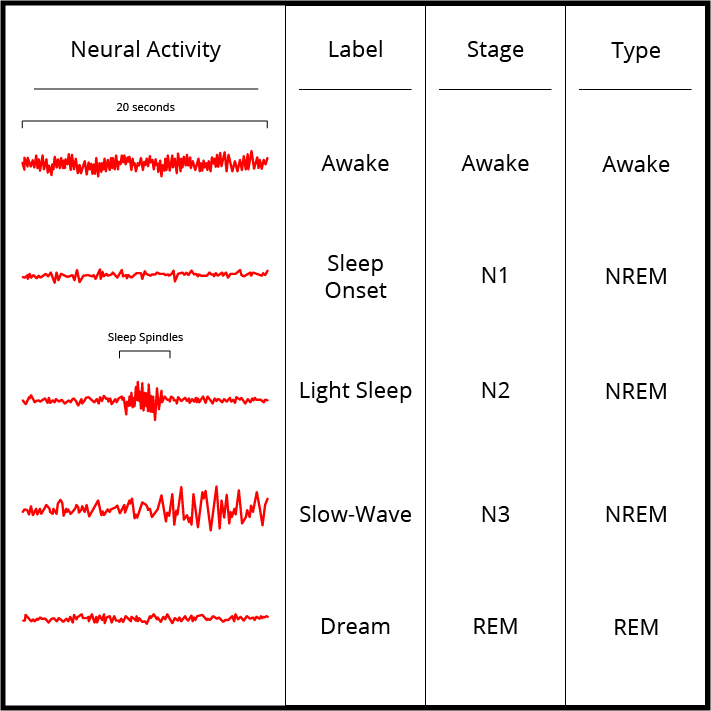

Interestingly, sleep itself is more than shutting off for the night (or for a nap). Instead of turning off like a light with a flick of a switch, your shift in consciousness is reflected in your brain’s electrical activity. While you are awake and alert your brain activity is marked by betawaves. Beta waves are characterized by being high in frequency but low in intensity. In addition, they are the most inconsistent brain wave and this reflects the wide variation in sensory input that a person processes during the day. As you begin to relax these change to alpha waves. These waves reflect brain activity that is less frequent, more consistent and more intense. As you slip into actual sleep you transition through many stages. Scholars differ on how they characterize sleep stages with some experts arguing that there are four distinct stages (Manoach et al., 2010), while others recognize five (Šušmáková, & Krakovská, 2008) but they all distinguish between those that include rapid eye movement (REM) and those that are non-rapid eye movement (NREM). In addition, each stage is typically characterized by its own unique pattern of brain activity:

- Stage 1 (called NREM 1, or N1) is the “falling asleep” stage and is marked by theta waves.

- Stage 2 (called NREM 2, or N2) is considered a light sleep. Here, there are occasional “sleep spindles,” or very high intensity brain waves. These are thought to be associated with the processing of memories. NREM 2 makes up about 55% of all sleep.

- Stage 3 (called NREM 3, or N3) makes up between 20-25% of all sleep and is marked by greater muscle relaxation and the appearance of delta waves.

- Finally, REM sleep is marked by rapid eye movement (REM). Interestingly, this stage—in terms of brain activity—is similar to wakefulness. That is, the brain waves occur less intensely than in other stages of sleep. REM sleep accounts for about 20% of all sleep and is associated with dreaming.

Dreams are, arguably, the most interesting aspect of sleep. Throughout history dreams have been given special importance because of their unique, almost mystical nature. They have been thought to be predictions of the future, hints of hidden aspects of the self, important lessons about how to live life, or opportunities to engage in impossible deeds like flying. There are several competing theories of why humans dream. One is that it is our nonconscious attempt to make sense of our daily experiences and learning. Another, popularized by Freud, is that dreams represent taboo or troublesome wishes or desires. Regardless of the specific reason we know a few facts about dreams: all humans dream, we dream at every stage of sleep, but dreams during REM sleep are especially vivid. One under-explored area of dream research is the possible social functions of dreams: we often share our dreams with others and use them for entertainment value.

Sleep serves many functions, one of which is to give us a period of mental and physical restoration. Children generally need more sleep than adults since they are developing. It is so vital, in fact, that a lack of sleep is associated with a wide range of problems. People who do not receive adequate sleep are more irritable, have slower reaction time, have more difficulty sustaining attention, and make poorer decisions. Interestingly, this is an issue relevant to the lives of college students. In one highly cited study researchers found that 1 in 5 students took more than 30 minutes to fall asleep at night, 1 in 10 occasionally took sleep medications, and more than half reported being “mostly tired” in the mornings (Buboltz, et al, 2001).

Psychoactive Drugs

On April 16, 1943, Albert Hoffman—a Swiss chemist working in a pharmaceutical company—accidentally ingested a newly synthesized drug. The drug—lysergic acid diethylimide (LSD)—turned out to be a powerful hallucinogen. Hoffman went home and later reported the effects of the drug, describing them as seeing the world through a “warped mirror” and experiencing visions of “extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.” Hoffman had discovered what members of many traditional cultures around the world already knew: there are substances that, when ingested, can have a powerful effect on perception and on consciousness.

Drugs operate on human physiology in a variety of ways and researchers and medical doctors tend to classify drugs according to their effects. Here we will briefly cover 3 categories of drugs: hallucinogens, depressants, and stimulants.

Hallucinogens

It is possible that hallucinogens are the substance that have, historically, been used the most widely. Traditional societies have used plant-based hallucinogens such as peyote, ebene, and psilocybin mushrooms in a wide range of religious ceremonies. Hallucinogens are substances that alter a person’s perceptions, often by creating visions or hallucinations that are not real. There are a wide range of hallucinogens and many are used as recreational substances in industrialized societies. Common examples include marijuana, LSD, and MDMA (also known as “ecstasy”). Marijuana is the dried flowers of the hemp plant and is often smoked to produce euphoria. The active ingredient in marijuana is called THC and can produce distortions in the perception of time, can create a sense of rambling, unrelated thoughts, and is sometimes associated with increased hunger or excessive laughter. The use and possession of marijuana is illegal in most places but this appears to be a trend that is changing. Uruguay, Bangladesh, and several of the United States, have recently legalized marijuana. This may be due, in part, to changing public attitudes or to the fact that marijuana is increasingly used for medical purposes such as the management of nausea or treating glaucoma.

Depressants

Depressants are substances that, as their name suggests, slow down the body’s physiology and mental processes. Alcohol is the most widely used depressant. Alcohol’s effects include the reduction of inhibition, meaning that intoxicated people are more likely to act in ways they would otherwise be reluctant to. Alcohol’s psychological effects are the result of it increasing the neurotransmitter GABA. There are also physical effects, such as loss of balance and coordination, and these stem from the way that alcohol interferes with the coordination of the visual and motor systems of the brain. Despite the fact that alcohol is so widely accepted in many cultures it is also associated with a variety of dangers. First, alcohol is toxic, meaning that it acts like a poison because it is possible to drink more alcohol than the body can effectively remove from the bloodstream. When a person’s blood alcohol content (BAC) reaches .3 to .4% there is a serious risk of death. Second, the lack of judgment and physical control associated with alcohol is associated with more risk taking behavior or dangerous behavior such as drunk driving. Finally, alcohol is addictive and heavy drinkers often experience significant interference with their ability to work effectively or in their close relationships.

Other common depressants include opiates (also called “narcotics”), which are substances synthesized from the poppy flower. Opiates stimulate endorphin production in the brain and because of this they are often used as pain killers by medical professionals. Unfortunately, because opiates such as Oxycontin so reliably produce euphoria they are increasingly used—illegally—as recreational substances. Opiates are highly addictive.

Stimulants

Stimulants are substances that “speed up” the body’s physiological and mental processes. Two commonly used stimulants are caffeine—the drug found in coffee and tea—and nicotine, the active drug in cigarettes and other tobacco products. These substances are both legal and relatively inexpensive, leading to their widespread use. Many people are attracted to stimulants because they feel more alert when under the influence of these drugs. As with any drug there are health risks associated with consumption. For example, excessive consumption of these types of stimulants can result in anxiety, headaches, and insomnia. Similarly, smoking cigarettes—the most common means of ingesting nicotine—is associated with higher risks of cancer. For instance, among heavy smokers 90% of lung cancer is directly attributable to smoking (Stewart & Kleihues, 2003).

There are other stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine (also known as “crystal meth” or “ice”) that are illegal substances that are commonly used. These substances act by blocking “re-uptake” of dopamine in the brain. This means that the brain does not naturally clear out the dopamine and that it builds up in the synapse, creating euphoria and alertness. As the effects wear off it stimulates strong cravings for more of the drug. Because of this these powerful stimulants are highly addictive.

Conclusion

When you think about your daily life it is easy to get lulled into the belief that there is one “setting” for your conscious thought. That is, you likely believe that you hold the same opinions, values, and memories across the day and throughout the week. But “you” are like a dimmer switch on a light that can be turned from full darkness increasingly on up to full brightness. This switch is consciousness. At your brightest setting you are fully alert and aware; at dimmer settings you are day dreaming; and sleep or being knocked unconscious represent dimmer settings still. The degree to which you are in high, medium, or low states of conscious awareness affect how susceptible you are to persuasion, how clear your judgment is, and how much detail you can recall. Understanding levels of awareness, then, is at the heart of understanding how we learn, decide, remember and many other vital psychological processes.

Outside Resources

- Web: Learn more about motion-induced blindness on Michael Bach\\\’s website

- http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/mot-mib/index.html

- App: Visual illusions for the iPad.

- http://www.exploratorium.edu/explore/apps/color-uncovered

- Web: Definitions of Consciousness

- http://www.consciousentities.com/definitions.htm

- Video: Ted Talk – Simon Lewis: Don’t take consciousness for granted

- http://www.ted.com/talks/simon_lewis_don_t_take_consciousness_for_granted.html

- Book: A wonderful book about how little we know about ourselves: Wilson, T. D. (2004). Strangers to ourselves. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674013827

- Book: Another wonderful book about free will—or its absence?: Wegner, D. M. (2002). The illusion of conscious will. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/illusion-conscious-will

- Information on alcoholism, alcohol abuse, and treatment:

- http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/support-treatment

- The American Psychological Association has information on getting a good night’s sleep as well as on sleep disorders

- http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/sleep-disorders.aspx

- The National Sleep Foundation is a non-profit with videos on insomnia, sleep training in children, and other topics

- https://sleepfoundation.org/video-library

- Video: An artist who periodically took LSD and drew self-portraits:

- http://www.openculture.com/2013/10/artist-draws-nine-portraits-on-lsd-during-1950s-research-experiment.html

- Video: An interesting video on attention:

- http://www.dansimons.com/videos.html

- Web: A good overview of priming:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Priming_(psychology)

- Web: Definitions of Consciousness:

- http://www.consciousentities.com/definitions.htm

- Web: Learn more about motion-induced blindness on Michael Bach\’s website:

- http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/mot-mib/index.html

Discussion Questions

- Why has consciousness evolved? Presumably it provides some beneficial capabilities for an organism beyond behaviors that are based only on automatic triggers or unconscious processing. What are the likely benefits of consciousness?

- How would you explain to a congenitally blind person the experience of seeing red? Detailed explanations of the physics of light and neurobiology of color processing in the brain would describe the mechanisms that give rise to the experience of seeing red, but would not convey the experience. What would be the best way to communicate the subjective experience itself?

- Our visual experiences seem to be a direct readout of information from the world that comes into our eyes, and we usually believe that our mental representations give us an accurate and exact re-creation of the world. Is it possible that what we consciously perceive is not veridical, but is a limited and distorted view, in large part a function of the specific sensory and information-processing abilities that the brain affords?

- When are you most conscious—while you’re calm, angry, happy, or moved; while absorbed in a movie, video game, or athletic activity; while engaged in a spirited conversation, making decisions, meditating, reflecting, trying to solve a difficult problem, day dreaming, or feeling creative? How do these considerations shed light on what consciousness is?

- Consciousness may be a natural biological phenomenon and a chief function of a brain, but consider the many ways in which it is also contingent on (i) a body linked with a brain, (ii) an outside world, (iii) a social environment, and (iv) a developmental trajectory. How do these considerations enrich our understanding of consciousness?

- Conscious experiences may not be limited to human beings. However, the difficulty of inferring consciousness in other beings highlights the limitations of our current understanding of consciousness. Many nonhuman animals may have conscious experiences; pet owners often have no doubt about what their pets are thinking. Computers with sufficient complexity might at some point be conscious—but how would we know?

- If someone were in a coma after an accident, and you wanted to better understand how “conscious” or aware s/he were, how might you go about it?

- What are some of the factors in daily life that interfere with people’s ability to get adequate sleep? What interferes with your sleep?

- How frequently do you remember your dreams? Do you have recurring images or themes in your dreams? Why do you think that is?

- Consider times when you fantasize or let your mind wander? Describe these times: are you more likely to be alone or with others? Are there certain activities you engage in that seem particularly prone to daydreaming?

- A number of traditional societies use consciousness altering substances in ceremonies. Why do you think they do this?

- Do you think attitudes toward drug use are changing over time? If so, how? Why do you think these changes occur?

- Students in high school and college are increasingly using stimulants such as Adderol as study aids and “performance enhancers.” What is your opinion of this trend?

Vocabulary

- Awareness

- A conscious experience or the capability of having conscious experiences, which is distinct from self-awareness, the conscious understanding of one’s own existence and individuality.

- Conscious experience

- The first-person perspective of a mental event, such as feeling some sensory input, a memory, an idea, an emotion, a mood, or a continuous temporal sequence of happenings.

- Contemplative science

- A research area concerned with understanding how contemplative practices such as meditation can affect individuals, including changes in their behavior, their emotional reactivity, their cognitive abilities, and their brains. Contemplative science also seeks insights into conscious experience that can be gained from first-person observations by individuals who have gained extraordinary expertise in introspection.

- First-person perspective

- Observations made by individuals about their own conscious experiences, also known as introspection or a subjective point of view. Phenomenology refers to the description and investigation of such observations.

- Third-person perspective

- Observations made by individuals in a way that can be independently confirmed by other individuals so as to lead to general, objective understanding. With respect to consciousness, third-person perspectives make use of behavioral and neural measures related to conscious experiences.

- Blood Alcohol Content (BAC)

- Blood Alcohol Content (BAC): a measure of the percentage of alcohol found in a person’s blood. This measure is typically the standard used to determine the extent to which a person is intoxicated, as in the case of being too impaired to drive a vehicle.

- Circadian Rhythm

- Circadian Rhythm: The physiological sleep-wake cycle. It is influenced by exposure to sunlight as well as daily schedule and activity. Biologically, it includes changes in body temperature, blood pressure and blood sugar.

- Consciousness

- Consciousness: the awareness or deliberate perception of a stimulus

- Cues

- Cues: a stimulus that has a particular significance to the perceiver (e.g., a sight or a sound that has special relevance to the person who saw or heard it)

- Depressants

- Depressants: a class of drugs that slow down the body’s physiological and mental processes.

- Dissociation

- Dissociation: the heightened focus on one stimulus or thought such that many other things around you are ignored; a disconnect between one’s awareness of their environment and the one object the person is focusing on

- Euphoria

- Euphoria: an intense feeling of pleasure, excitement or happiness.

- Flexible Correction Model

- Flexible Correction Model: the ability for people to correct or change their beliefs and evaluations if they believe these judgments have been biased (e.g., if someone realizes they only thought their day was great because it was sunny, they may revise their evaluation of the day to account for this “biasing” influence of the weather)

- Hallucinogens

- Hallucinogens: substances that, when ingested, alter a person’s perceptions, often by creating hallucinations that are not real or distorting their perceptions of time.

- Hypnosis

- Hypnosis: the state of consciousness whereby a person is highly responsive to the suggestions of another; this state usually involves a dissociation with one’s environment and an intense focus on a single stimulus, which is usually accompanied by a sense of relaxation

- Hypnotherapy

- Hypnotherapy: The use of hypnotic techniques such as relaxation and suggestion to help engineer desirable change such as lower pain or quitting smoking.

- Implicit Associations Test

- Implicit Associations Test (IAT): A computer reaction time test that measures a person’s automatic associations with concepts. For instance, the IAT could be used to measure how quickly a person makes positive or negative evaluations of members of various ethnic groups.

- Jet Lag

- Jet Lag: The state of being fatigued and/or having difficulty adjusting to a new time zone after traveling a long distance (across multiple time zones).

- Melatonin

- Melatonin: A hormone associated with increased drowsiness and sleep.

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness: a state of heightened focus on the thoughts passing through one’s head, as well as a more controlled evaluation of those thoughts (e.g., do you reject or support the thoughts you’re having?)

- Priming

- Priming: the activation of certain thoughts or feelings that make them easier to think of and act upon

- Stimulants

- Stimulants: a class of drugs that speed up the body’s physiological and mental processes.

- Trance States

- Trance: a state of consciousness characterized by the experience of “out-of-body possession,” or an acute dissociation between one’s self and the current, physical environment surrounding them.

References

- Blackmore, S. (2006). Conversations on consciousness: What the best minds think about the brain, free will, and what it means to be human. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Casali, A. G., Gosseries, O., Rosanova, M., Boly, M. Sarasso, S., Casali, K. R., Casarotto, S., Bruno, M.-A., Laureys, S., Tononi, G., & Massimini, M. (2013). A theoretically based index of consciousness independent of sensory processing and behavior. Science Translational Medicine, 5, 198ra105

- Dane, E., Rockmann, K. W., & Pratt, M. G. (2012). When should I trust my gut? Linking domain expertise to intuitive decision-making effectiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 119, 187–194.

- Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J.-P. (2011). Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron, 70, 200–227.

- Dehaene, S., Naccache, L., Le Clec’H, G., Koechlin, E., Mueller, M., Dehaene-Lambertz, G., van de Moortele, P.-F., & Le Bihan, D. (1998). Imaging unconscious semantic priming. Nature, 395, 597–600.

- Graziano, M. S. A., & Kastner, S. (2011). Human consciousness and its relationship to social neuroscience: A novel hypothesis. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2, 98–113.

- Koch, C. (2012). Consciousness: Confessions of a romantic reductionist. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lamme, V. A. F. (2001). Blindsight: The role of feedforward and feedback corticocortical connections. Acta Psychologica, 107, 209–228.

- Monti, M. M., Lutkenhoff, E. S., Rubinov, M., Boveroux, P., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., Gosseries O., Bruno, M. A., Noirhomme, Q., Boly, M., & Laureys S. (2013) Dynamic change of global and local information processing in propofol-induced loss and recovery of consciousness. PLoS Comput Biol 9(10): e1003271. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003271

- Paller, K. A., Voss, J. L., & Westerberg, C. E. (2009). Investigating the awareness of remembering. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 185–199.

- Pascual-Leone, A., & Walsh, V. (2001). Fast backprojections from the motion to the primary visual area necessary for visual awareness. Science, 292, 510–512.

- Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H.-J., & Haynes, J.-D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decision in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 543–545.

- Tononi, G. (2004). An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neuroscience, 5(42), 1–22. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2202/5/42/

- Voss, J. L., Lucas, H. D., & Paller, K. A. (2012). More than a feeling: Pervasive influences of memory processing without awareness of retrieval. Cognitive Neuroscience, 3, 193–207.

- Zelazo, P. D., Moscovitch, M., & Thompson, E. (2007). The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Zeman, A. (2002). A user’s guide to consciousness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- de Lange, F., van Gaal, S., Lamme, V., & Dehaene, S. (2011). How awareness changes the relative weights of evidence during human decision making. PLOS-Biology, 9, e1001203.

- Abbot, N. C., Stead, L. F., White, A. R., Barnes, J., & Ernst, E. (1998). Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2.

- Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230.

- Buboltz, W., Brown, F. & Soper, B. (2001). Sleep habits and patterns of college students: A preliminary study. Journal of American College Health, 50, 131-135.

- Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752.

- Ewin, D. M. (1978). Clinical use of hypnosis for attenuation of burn depth. Hypnosis at its Bicentennial-Selected Papers from the Seventh International Congress of Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine. New York: Plenum Press.

- Freud, S. (2001). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams (First Part) (Vol. 4). Random House.

- Gilbert, D. T., & Hixon, J. G. (1991). The trouble of thinking: activation and application of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 509.

- Greenwald, A. G., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the Implicit Association Test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1022-1038.

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. K. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464-1480.

- Kihlstrom, J.F. (2003). Hypnosis and memory. In J.F. Byrne (Ed.), Learning and memory, 2nd ed. (pp. 240-242). Farmington Hills, Mi.: Macmillan Reference

- Kirsch, I., & Lynn, S. J. (1995). Altered state of hypnosis: Changes in the theoretical landscape. American Psychologist, 50(10), 846.

- Lynn S. J., and Kirsch I. (2006). Essentials of clinical hypnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Lynn, S. J., Rhue, J. W., & Weekes, J. R. (1990). Hypnotic involuntariness: A social-cognitive analysis. Psychological Review, 97, 169–184.

- Manoach, D. S., Thakkar, K. N., Stroynowski, E., Ely, A., McKinley, S. K., Wamsley, E., … & Stickgold, R. (2010). Reduced overnight consolidation of procedural learning in chronic medicated schizophrenia is related to specific sleep stages. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(2), 112-120.

- Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration website. Group Dynamics, 6(1), 101-115.

- Patterson, D. R., Everett, J. J., Burns, G. L., & Marvin, J. A. (1992). Hypnosis for the treatment of burn pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 713-17

- Pekala, R. J., Kumar, V. K., Maurer, R., Elliott-Carter, N., Moon, E., & Mullen, K. (2010). Suggestibility, expectancy, trance state effects, and hypnotic depth: I. Implications for understanding hypnotism. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 52(4), 275-290.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 19, pp. 123-205). New York: Academic Press.

- Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433-447.

- Stewart, B. & Kleinhues, P. (2003). World cancer report. World Health Organization.

- Syrjala, K. L., Cummings, C., & Donaldson, G. W. (1992). Hypnosis or cognitive behavioral training for the reduction of pain and nausea during cancer treatment: A controlled clinical trial. Pain, 48, 137-46.

- Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1997). The flexible correction model: The role of naive theories of bias in bias correction. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 142-208.

- Wickramasekera II, I. E., & Szlyk, J. (2003). Could empathy be a predictor of hypnotic ability? International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 51(4), 390–399.

- Williams, L. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science, 322(5901), 606-607.

- Öhman, A., & Soares, J. J. (1994). \”Unconscious anxiety\”: phobic responses to masked stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(2), 231.

- Šušmáková, K., & Krakovská, A. (2008). Discrimination ability of individual measures used in sleep stages classification. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 44(3), 261-277.

Authors

Ken Paller

Ken PallerKen Paller is a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University, Professor in the Department of Psychology, and Director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program. Research in his laboratory focuses on various aspects of human memory, including contrasts between conscious and nonconscious memory expressions, accurate guessing based on implicit knowledge, and memory consolidation during sleep.

Satoru Suzuki

Satoru SuzukiSatoru Suzuki studied physics and music composition at Wesleyan University. He pursued physics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, hoping to understand the universe, but realized that consciousness is at the heart of understanding everything. He studied visual perception at Harvard University, and now investigates how human experience arises from conscious and unconscious interactions with the environment.

Robert Biswas-Diener

Robert Biswas-DienerDr. Robert Biswas-Diener is a part-time instructor at Portland State University and is senior editor of Noba. He has more than 50 publications on happiness and other positive topics in peer-reviewed journals. He is author of The Upside of Your Dark Side.

Jake Teeny

Jake TeenyJake Teeny received his M.A. in social psychology from The Ohio State University, where he now pursuing a PhD. His research examines when and why people advocate their beliefs. In addition to his psychological work, he also writes short fiction, both of which can be found at www.jaketeeny.com

Creative Commons License

States of Consciousness by Robert Biswas-Diener and Jake Teeny is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

States of Consciousness by Robert Biswas-Diener and Jake Teeny is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Creative Commons License

Consciousness by Ken Paller and Satoru Suzuki is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Consciousness by Ken Paller and Satoru Suzuki is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.