Contents

- 1 An Introduction to the Science of Social Psychology

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Social Psychology is a Science

- 4 What is Included in Social Psychology?

- 5 Conclusion

- 6 Culture

- 7 Introduction

- 8 Social Psychology Research Methods

- 9 What is Culture?

- 10 The Self and Culture

- 11 Culture is Learned

- 12 Cultural Relativism

- 13 Conclusion

An Introduction to the Science of Social Psychology

Portland State University

The science of social psychology investigates the ways other people affect our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It is an exciting field of study because it is so familiar and relevant to our day-to-day lives. Social psychologists study a wide range of topics that can roughly be grouped into 5 categories: attraction, attitudes, peace & conflict, social influence, and social cognition.

Learning Objectives

- Define social psychology and understand how it is different from other areas of psychology.

- Understand “levels of analysis” and why this concept is important to science.

- List at least three major areas of study in social psychology.

- Define the “need to belong”.

Introduction

We live in a world where, increasingly, people of all backgrounds have smart phones. In economically developing societies, cellular towers are often less expensive to install than traditional landlines. In many households in industrialized societies, each person has his or her own mobile phone instead of using a shared home phone. As this technology becomes increasingly common, curious researchers have wondered what effect phones might have on relationships. Do you believe that smart phones help foster closer relationships? Or do you believe that smart phones can hinder connections? In a series of studies, researchers have discovered that the mere presence of a mobile phone lying on a table can interfere with relationships. In studies of conversations between both strangers and close friends—conversations occurring in research laboratories and in coffee shops—mobile phones appeared to distract people from connecting with one another. The participants in these studies reported lower conversation quality, lower trust, and lower levels of empathy for the other person (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2013). This is not to discount the usefulness of mobile phones, of course. It is merely a reminder that they are better used in some situations than they are in others. It is also a real-world example of how social psychology can help produce insights about the ways we understand and interact with one another.

Social psychology is the branch of psychological science mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Just as clinical psychology focuses on mental disorders and their treatment, and developmental psychology investigates the way people change across their lifespan, social psychology has its own focus. As the name suggests, this science is all about investigating the ways groups function, the costs and benefits of social status, the influences of culture, and all the other psychological processes involving two or more people.

Social psychology is such an exciting science precisely because it tackles issues that are so familiar and so relevant to our everyday life. Humans are “social animals.” Like bees and deer, we live together in groups. Unlike those animals, however, people are unique, in that we care a great deal about our relationships. In fact, a classic study of life stress found that the most stressful events in a person’s life—the death of a spouse, divorce, and going to jail—are so painful because they entail the loss of relationships (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). We spend a huge amount of time thinking about and interacting with other people, and researchers are interested in understanding these thoughts and actions. Giving up a seat on the bus for another person is an example of social psychology. So is disliking a person because he is wearing a shirt with the logo of a rival sports team. Flirting, conforming, arguing, trusting, competing—these are all examples of topics that interest social psychology researchers.

At times, science can seem abstract and far removed from the concerns of daily life. When neuroscientists discuss the workings of the anterior cingulate cortex, for example, it might sound important. But the specific parts of the brain and their functions do not always seem directly connected to the stuff you care about: parking tickets, holding hands, or getting a job. Social psychology feels so close to home because it often deals with universal psychological processes to which people can easily relate. For example, people have a powerful need to belong(Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It doesn’t matter if a person is from Israel, Mexico, or the Philippines; we all have a strong need to make friends, start families, and spend time together. We fulfill this need by doing things such as joining teams and clubs, wearing clothing that represents “our group,” and identifying ourselves based on national or religious affiliation. It feels good to belong to a group. Research supports this idea. In a study of the most and least happy people, the differentiating factor was not gender, income, or religion; it was having high-quality relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2002). Even introverts report being happier when they are in social situations (Pavot, Diener & Fujita, 1990). Further evidence can be found by looking at the negative psychological experiences of people who do not feel they belong. People who feel lonely or isolated are more vulnerable to depression and problems with physical health (Cacioppo, & Patrick, 2008).

Social Psychology is a Science

The need to belong is also a useful example of the ways the various aspects of psychology fit together. Psychology is a science that can be sub-divided into specialties such as “abnormal psychology” (the study of mental illness) or “developmental psychology” (the study of how people develop across the life span). In daily life, however, we don’t stop and examine our thoughts or behaviors as being distinctly social versus developmental versus personality-based versus clinical. In daily life, these all blend together. For example, the need to belong is rooted in developmental psychology. Developmental psychologists have long paid attention to the importance of attaching to a caregiver, feeling safe and supported during childhood, and the tendency to conform to peer pressure during adolescence. Similarly, clinical psychologists—those who research mental disorders– have pointed to people feeling a lack of belonging to help explain loneliness, depression, and other psychological pains. In practice, psychologists separate concepts into categories such as “clinical,” “developmental,” and “social” only out of scientific necessity. It is easier to simplify thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in order to study them. Each psychological sub-discipline has its own unique approaches to research. You may have noticed that this is almost always how psychology is taught, as well. You take a course in personality, another in human sexuality, and a third in gender studies, as if these topics are unrelated. In day-to-day life, however, these distinctions do not actually exist, and there is heavy overlap between the various areas of psychology.

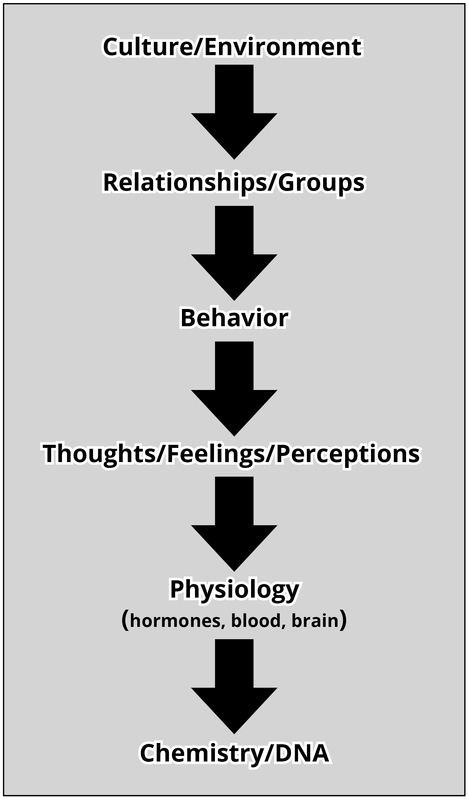

In psychology, there are varying levels of analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the different levels at which scientists might understand a single event. Take the example of a toddler watching her mother make a phone call: the toddler is curious, and is using observational learning to teach herself about this machine called a telephone. At the most specific levels of analysis, we might understand that various neurochemical processes are occurring in the toddler’s brain. We might be able to use imaging techniques to see that the cerebellum, among other parts of the brain, is activated with electrical energy. If we could “pull back” our scientific lens, we might also be able to gain insight into the toddler’s own experience of the phone call. She might be confused, interested, or jealous. Moving up to the next level of analysis, we might notice a change in the toddler’s behavior: during the call she furrows her brow, squints her eyes, and stares at her mother and the phone. She might even reach out and grab at the phone. At still another level of analysis, we could see the ways that her relationships enter into the equation. We might observe, for instance, that the toddler frowns and grabs at the phone when her mother uses it, but plays happily and ignores it when her stepbrother makes a call. All of these chemical, emotional, behavioral, and social processes occur simultaneously. None of them is the objective truth. Instead, each offers clues into better understanding what, psychologically speaking, is happening.

Social psychologists attend to all levels of analysis but—historically—this branch of psychology has emphasized the higher levels of analysis. Researchers in this field are drawn to questions related to relationships, groups, and culture. This means that they frame their research hypotheses in these terms. Imagine for a moment that you are a social researcher. In your daily life, you notice that older men on average seem to talk about their feelings less than do younger men. You might want to explore your hypothesis by recording natural conversations between males of different ages. This would allow you to see if there was evidence supporting your original observation. It would also allow you to begin to sift through all the factors that might influence this phenomenon: What happens when an older man talks to a younger man? What happens when an older man talks to a stranger versus his best friend? What happens when two highly educated men interact versus two working class men? Exploring each of these questions focuses on interactions, behavior, and culture rather than on perceptions, hormones, or DNA.

In part, this focus on complex relationships and interactions is one of the things that makes research in social psychology so difficult. High quality research often involves the ability to control the environment, as in the case of laboratory experiments. The research laboratory, however, is artificial, and what happens there may not translate to the more natural circumstances of life. This is why social psychologists have developed their own set of unique methods for studying attitudes and social behavior. For example, they use naturalistic observation to see how people behave when they don’t know they are being watched. Whereas people in the laboratory might report that they personally hold no racist views or opinions (biases most people wouldn’t readily admit to), if you were to observe how close they sat next to people of other ethnicities while riding the bus, you might discover a behavioral clue to their actual attitudes and preferences.

What is Included in Social Psychology?

Social psychology is the study of group processes: how we behave in groups, and how we feel and think about one another. While it is difficult to summarize the many areas of social psychology research, it can be helpful to lump them into major categories as a starting point to wrap our minds around. There is, in reality, no specific number of definitive categories, but for the purpose of illustration, let’s use five. Most social psychology research topics fall into one (but sometimes more) of each of these areas:

Attraction

A large amount of study in social psychology has focused on the process of attraction. Think about a young adult going off to college for the first time. He takes an art history course and sits next to a young woman he finds attractive. This feeling raises several interesting questions: Where does the attraction come from? Is it biological or learned? Why do his standards for beauty differ somewhat from those of his best friend? The study of attraction covers a huge range of topics. It can begin with first impressions, then extend to courtship and commitment. It involves the concepts of beauty, sex, and evolution. Attraction researchers might study stalking behavior. They might research divorce or remarriage. They might study changing standards of beauty across decades.

In a series of studies focusing on the topic of attraction, researchers were curious how people make judgments of the extent to which the faces of their friends and of strangers are good looking (Wirtz, Biswas-Diener, Diener & Drogos, 2011). To do this, the researchers showed a set of photographs of faces of young men and women to several assistants who were blind to the research hypothesis. Some of the people in the photos were Caucasian, some were African-American, and some were Maasai, a tribe of traditional people from Kenya. The assistants were asked to rate the various facial features in the photos, including skin smoothness, eye size, prominence of cheekbones, symmetry (how similar the left and the right halves of the face are), and other characteristics. The photos were then shown to the research participants—of the same three ethnicities as the people in the photos—who were asked to rate the faces for overall attractiveness. Interestingly, when rating the faces of strangers, white people, Maasai, and African-Americans were in general agreement about which faces were better looking. Not only that, but there was high consistency in which specific facial features were associated with being good looking. For instance, across ethnicities and cultures, everyone seemed to find smooth skin more attractive than blemished skin. Everyone seemed to also agree that larger chins made men more attractive, but not women.

Then came an interesting discovery. The researchers found that Maasai tribal people agreed about the faces of strangers—but not about the faces of people they knew! Two people might look at the same photo of someone they knew; one would give a thumbs up for attractiveness, the other one, not so much. It appeared that friends were using some other standard of beauty than simply nose, eyes, skin, and other facial features. To explore this further, the researchers conducted a second study in the United States. They brought university students into their laboratory in pairs. Each pair were friends; some were same-sex friends and some were opposite-sex friends. They had their photographs taken and were then asked to privately rate each other’s attractiveness, along with photos of other participants whom they did not know (strangers). Friends were also asked to rate each other on personality traits, including “admirable,” “generous,” “likable,” “outgoing,” “sensitive,” and “warm.”

In doing this, the researchers discovered two things. First, they found the exact same pattern as in the earlier study: when the university students rated strangers, they focused on actual facial features, such as skin smoothness and large eyes, to make their judgments (whether or not they realized it). But when it came to the hotness-factor of their friends, these features appeared not to be very important. Suddenly, likable personality characteristics were a better predictor of who was considered good looking. This makes sense. Attractiveness is, in part, an evolutionary and biological process. Certain features such as smooth skin are signals of health and reproductive fitness—something especially important when scoping out strangers. Once we know a person, however, it is possible to swap those biological criteria for psychological ones. People tend to be attracted not just to muscles and symmetrical faces but also to kindness and generosity. As more information about a person’s personality becomes available, it becomes the most important aspect of a person’s attractiveness.

Understanding how attraction works is more than an intellectual exercise; it can also lead to better interventions. Insights from studies on attraction can find their way into public policy conversations, couples therapy, and sex education programs.

Attitudes

Social psychology shares with its intellectual cousins sociology and political science an interest in attitudes. Attitudes are opinions, feelings, and beliefs about a person, concept, or group. People hold attitudes about all types of things: the films they see, political issues, and what constitutes a good date. Social psychology researchers are interested in what attitudes people hold, where these attitudes come from, and how they change over time. Researchers are especially interested in social attitudes people hold about categories of people, such as the elderly, military veterans, or people with mental disabilities.

Among the most studied topics in attitude research are stereotyping and prejudice. Although people often use these words interchangeably, they are actually different concepts. Stereotyping is a way of using information shortcuts about a group to effectively navigate social situations or make decisions. For instance, you might hold a stereotype that elderly people are physically slower and frailer than twenty-year-olds. If so, you are more likely to treat interactions with the elderly in a different manner than interactions with younger people. Although you might delight in jumping on your friend’s back, punching a buddy in the arm, or jumping out and scaring a friend you probably do not engage in these behaviors with the elderly. Stereotypical information may or may not be correct. Also, stereotypical information may be positive or negative. Regardless of accuracy, all people use stereotypes, because they are efficient and inescapable ways to deal with huge amounts of social information. It is important to keep in mind, however, that stereotypes, even if they are correct in general, likely do not apply to every member of the group. As a result, it can seem unfair to judge an individual based on perceived group norms.

Prejudice, on the other hand, refers to how a person feels about an individual based on their group membership. For example, someone with a prejudice against tattoos may feel uncomfortable sitting on the metro next to a young man with multiple, visible tattoos. In this case, the person is pre-judging the man with tattoos based on group members (people with tattoos) rather than getting to know the man as an individual. Like stereotypes, prejudice can be positive or negative.

Discrimination occurs when a person is biased against an individual, simply because of the individual’s membership in a social category. For instance, if you were to learn that a person has gone to rehabilitation for alcohol treatment, it might be unfair to treat him or her as untrustworthy. You might hold a stereotype that people who have been involved with drugs are untrustworthy or that they have an arrest record. Discrimination would come when you act on that stereotype by, for example, refusing to hire the person for a job for which they are otherwise qualified. Understanding the psychological mechanisms of problems like prejudice can be the first step in solving them.

Social psychology focuses on basic processes, but also on applications. That is, researchers are interested in ways to make the world a better place, so they look for ways to put their discoveries into constructive practice. This can be clearly seen in studies on attitude change. In such experiments, researchers are interested in how people can overcome negative attitudes and feel more empathy towards members of other groups. Take, for example, a study by Daniel Batson and his colleagues (1997) on attitudes about people from stigmatized groups. In particular, the researchers were curious how college students in their study felt about homeless people. They had students listen to a recording of a fictitious homeless man—Harold Mitchell—describing his life. Half of the participants were told to be objective and fair in their consideration of his story. The other half were instructed to try to see life through Harold’s eyes and imagine how he felt. After the recording finished, the participants rated their attitudes toward homeless people in general. They addressed attitudes such as “Most homeless people could get a job if they wanted to,” or “Most homeless people choose to live that way.” It turns out that when people are instructed to have empathy—to try to see the world through another person’s eyes—it gives them not only more empathy for that individual, but also for the group as a whole. In the Batson et al. experiment (1997), the high empathy participants reported a favorable rating of homeless people than did those participants in the low empathy condition.

Studies like these are important because they reveal practical possibilities for creating a more positive society. In this case, the results tell us that it is possible for people to change their attitudes and look more favorably on people they might otherwise avoid or be prejudiced against. In fact, it appears that it takes relatively little—simply the effort to see another’s point of view—to nudge people toward being a bit kinder and more generous toward one another. In a world where religious and political divisions are highly publicized, this type of research might be an important step toward working together.

Peace & Conflict

Social psychologists are also interested in peace and conflict. They research conflicts ranging from the small—such as a spat between lovers—to the large—such as wars between nations. Researchers are interested in why people fight, how they fight, and what the possible costs and benefits of fighting are. In particular, social psychologists are interested in the mental processes associated with conflict and reconciliation. They want to understand how emotions, thoughts, and sense of identity play into conflicts, as well as making up afterward.

Take, for instance, a 1996 study by Dov Cohen and his colleagues. They were interested in people who come from a “culture of honor”—that is, a cultural background that emphasizes personal or family reputation and social status. Cohen and his colleagues realized that cultural forces influence why people take offense and how they behave when others offend them. To investigate how people from a culture of honor react to aggression, the Cohen research team invited dozens of university students into the laboratory, half of whom were from a culture of honor. In their experiment, they had a research confederate “accidentally” bump the research participant as they passed one another in the hallway, then say “asshole” quietly. They discovered that people from the Northern United States were likely to laugh off the incident with amusement (only 35% became angry), while 85% of folks from the Southern United States—a culture of honor region—became angry.

In a follow-up study, the researchers were curious as to whether this anger would boil over and lead people from cultures of honor to react more violently than others (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996). In a cafeteria setting, the researchers “accidentally” knocked over drinks of people from cultures of honor as well as drinks of people not from honor cultures. As expected, the people from honor cultures became angrier; however, they did not act out more aggressively. Interestingly, in follow-up interviews, the people from cultures of honor said they would expect their peers—other people from their culture of honor—to act violently even though they, themselves, had not. This follow-up study provides insights into the links between emotions and social behavior. It also sheds light on the ways that people perceive certain groups.

This line of research is just a single example of how social psychologists study the forces that give rise to aggression and violence. Just as in the case of attitudes, a better understanding of these forces might help researchers, therapists, and policy makers intervene more effectively in conflicts.

Social Influence

Take a moment and think about television commercials. How influenced do you think you are by the ads you see? A very common perception voiced among psychology students is “Other people are influenced by ads, but not me!” To some degree, it is an unsettling thought that outside influences might sway us to spend money on, make decisions about, or even feel what they want us to. Nevertheless, none of us can escape social influence. Perhaps, more than any other topic, social influence is the heart and soul of social psychology. Our most famous studies deal with the ways that other people affect our behavior; they are studies on conformity—being persuaded to give up our own opinions and go along with the group—and obedience—following orders or requests from people in authority.

Among the most researched topics is persuasion. Persuasion is the act of delivering a particular message so that it influences a person’s behavior in a desired way. Your friends try to persuade you to join their group for lunch. Your parents try to persuade you to go to college and to take your studies seriously. Doctors try to persuade you to eat a healthy diet or exercise more often. And, yes, advertisers try to persuade you also. They showcase their products in a way that makes them seem useful, affordable, reliable, or cool.

One example of persuasion can be seen in a very common situation: tipping the serving staff at a restaurant. In some societies, especially in the United States, tipping is an important part of dining. As you probably know, servers hope to get a large tip in exchange for good service. One group of researchers was curious what servers do to coax diners into giving bigger tips. Occasionally, for instance, servers write a personal message of thanks on the bill. In a series of studies, the researchers were interested in how gift-giving would affect tipping. First, they had two male waiters in New York deliver a piece of foil-wrapped chocolate along with the bill at the end of the meal. Half of 66 diners received the chocolate and the other half did not. When patrons were given the unexpected sweet, they tipped, on average, 2% more (Strohmetz, Rind, Fisher & Lynn 2002).

In a follow-up study, the researchers changed the conditions. In this case, two female servers brought a small basket of assorted chocolates to the table (Strohmetz et al., 2002). In one research condition, they told diners they could pick two sweets; in a separate research condition, however, they told diners they could pick one sweet, but then—as the diners were getting ready to leave—the waiters returned and offered them a second sweet. In both situations, the diners received the same number of sweets, but in the second condition the waiters appeared to be more generous, as if they were making a personal decision to give an additional little gift. In both of these conditions the average amount of tips went up, but tips increased a whopping 21% in the “very generous” condition. The researchers concluded that giving a small gift puts people in the frame of mind to give a little something back, a principle called reciprocity.

Research on persuasion is very useful. Although it is tempting to dismiss it as a mere attempt by advertisers to get you to purchase goods and services, persuasion is used for many purposes. For example, medical professionals often hope people will donate their organs after they die. Donated organs can be used to train medical students, advance scientific discovery, or save other people’s lives through transplantation. For years, doctors and researchers tried to persuade people to donate, but relatively few people did. Then, policy makers offered an organ donation option for people getting their driver’s license, and donations rose. When people received their license, they could tick a box that signed them up for the organ donation program. By coupling the decision to donate organs with a more common event—getting a license—policy makers were able to increase the number of donors. Then, they had the further idea of “nudging” people to donate—by making them “opt out” rather than “opt in.” Now, people are automatically signed up to donate organs unless they make the effort to check a box indicating they don’t want to. By making organ donation the default, more people have donated and more lives have been saved. This is a small but powerful example of how we can be persuaded to behave certain ways, often without even realizing what is influencing us.

Social Cognition

You, me, all of us—we spend much of our time thinking about other people. We make guesses as to their honesty, their motives, and their opinions. Social cognition is the term for the way we think about the social world and how we perceive others. In some sense, we are continually telling a story in our own minds about the people around us. We struggle to understand why a date failed to show up, whether we can trust the notes of a fellow student, or if our friends are laughing at our jokes because we are funny or if they are just being nice. When we make educated guesses about the efforts or motives of others, this is called social attribution. We are “attributing” their behavior to a particular cause. For example, we might attribute the failure of a date to arrive on time to car trouble, forgetfulness, or the wrong-headed possibility that we are not worthy of being loved.

Because the information we have regarding other people’s motives and behavior is not as complete as our insights into our own, we are likely to make unreliable judgments of them. Imagine, for example, that a person on the freeway speeds up behind you, follows dangerously close, then swerves around and passes you illegally. As the driver speeds off into the distance you might think to yourself, “What a jerk!” You are beginning to tell yourself a story about why that person behaved that way. Because you don’t have any information about his or her situation—rushing to the hospital, or escaping a bank robbery?—you default to judgments of character: clearly, that driver is impatient, aggressive, and downright rude. If you were to do the exact same thing, however—cut someone off on the freeway—you would be less likely to attribute the same behavior to poor character, and more likely to chalk it up to the situation. (Perhaps you were momentarily distracted by the radio.) The consistent way we attribute people’s actions to personality traits while overlooking situational influences is called the fundamental attribution error.

The fundamental attribution error can also emerge in other ways. It can include groups we belong to versus opposing groups. Imagine, for example, that you are a fan of rugby. Your favorite team is the All Blacks, from New Zealand. In one particular match, you notice how unsporting the opposing team is. They appear to pout and seem to commit an unusually high number of fouls. Their fouling behavior is clearly linked to their character; they are mean people! Yet, when a player from the All Blacks is called for a foul, you may be inclined to see that as a bad call by the referee or a product of the fact that your team is pressured from a tough schedule and a number of injuries to their star players. This mental process allows a person to maintain his or her own high self-esteem while dismissing the bad behavior of others.

Conclusion

People are more connected to one another today than at any time in history. For the first time, it is easy to have thousands of acquaintances on social media. It is easier than ever before to travel and meet people from different cultures. Businesses, schools, religious groups, political parties, and governments interact more than they ever have. For the first time, people in greater numbers live clustered in cities than live spread out across rural settings. These changes have psychological consequences. Over the last hundred years, we have seen dramatic shifts in political engagement, ethnic relations, and even the very definition of family itself.

Social psychologists are scientists who are interested in understanding the ways we relate to one another, and the impact these relationships have on us, individually and collectively. Not only can social psychology research lead to a better understanding of personal relationships, but it can lead to practical solutions for many social ills. Lawmakers, teachers and parents, therapists, and policy makers can all use this science to help develop societies with less conflict and more social support.

Culture

By Robert Biswas-Diener and Neil Thin

Portland State University, University of Edinburgh

Although the most visible elements of culture are dress, cuisine and architecture, culture is a highly psychological phenomenon. Culture is a pattern of meaning for understanding how the world works. This knowledge is shared among a group of people and passed from one generation to the next. This module defines culture, addresses methodological issues, and introduces the idea that culture is a process. Understanding cultural processes can help people get along better with others and be more socially responsible.

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate culture as an evolutionary adaptation common to all humans.

- Understand cultural processes as variable patterns rather than as fixed scripts.

- Understand the difference between cultural and cross-cultural research methods.

- Appreciate cultural awareness as a source of personal well-being, social responsibility, and social harmony.

- Explain the difference between individualism and collectivism.

- Define “self-construal” and provide a real life example.

Introduction

When you think about different cultures, you likely picture their most visible features, such as differences in the way people dress, or in the architectural styles of their buildings. You might consider different types of food, or how people in some cultures eat with chopsticks while people in others use forks. There are differences in body language, religious practices, and wedding rituals. While these are all obvious examples of cultural differences, many distinctions are harder to see because they are psychological in nature.

Just as culture can be seen in dress and food, it can also be seen in morality, identity, and gender roles. People from around the world differ in their views of premarital sex, religious tolerance, respect for elders, and even the importance they place on having fun. Similarly, many behaviors that may seem innate are actually products of culture. Approaches to punishment, for example, often depend on cultural norms for their effectiveness. In the United States, people who ride public transportation without buying a ticket face the possibility of being fined. By contrast, in some other societies, people caught dodging the fare are socially shamed by having their photos posted publicly. The reason this campaign of “name and shame” might work in one society but not in another is that members of different cultures differ in how comfortable they are with being singled out for attention. This strategy is less effective for people who are not as sensitive to the threat of public shaming.

The psychological aspects of culture are often overlooked because they are often invisible. The way that gender roles are learned is a cultural process as is the way that people think about their own sense of duty toward their family members. In this module, you will be introduced to one of the most fascinating aspects of social psychology: the study of cultural processes. You will learn about research methods for studying culture, basic definitions related to this topic, and about the ways that culture affects a person’s sense of self.

Social Psychology Research Methods

Social psychologists are interested in the ways that cultural forces influence psychological processes. They study culture as a means of better understanding the ways it affects our emotions, identity, relationships, and decisions. Social psychologists generally ask different types of questions and use different methods than do anthropologists. Anthropologists are more likely to conduct ethnographic studies. In this type of research, the scientist spends time observing a culture and conducting interviews. In this way, anthropologists often attempt to understand and appreciate culture from the point of view of the people within it. Social psychologists who adopt this approach are often thought to be studying cultural psychology. They are likely to use interviews as a primary research methodology.

For example, in a 2004 study Hazel Markus and her colleagues wanted to explore class culture as it relates to well-being. The researchers adopted a cultural psychology approach and interviewed participants to discover—in the participants own words—what “the good life” is for Americans of different social classes. Dozens of participants answered 30 open ended questions about well-being during recorded, face-to-face interviews. After the interview data were collected the researchers then read the transcripts. From these, they agreed on common themes that appeared important to the participants. These included, among others, “health,” “family,” “enjoyment,” and “financial security.”

The Markus team discovered that people with a Bachelor’s Degree were more likely than high school educated participants to mention “enjoyment” as a central part of the good life. By contrast, those with a high school education were more likely to mention “financial security” and “having basic needs met.” There were similarities as well: participants from both groups placed a heavy emphasis on relationships with others. Their understanding of how these relationships are tied to well-being differed, however. The college educated—especially men—were more likely to list “advising and respecting” as crucial aspects of relationships while their high school educated counterparts were more likely to list “loving and caring” as important. As you can see, cultural psychological approaches place an emphasis on the participants’ own definitions, language, and understanding of their own lives. In addition, the researchers were able to make comparisons between the groups, but these comparisons were based on loose themes created by the researchers.

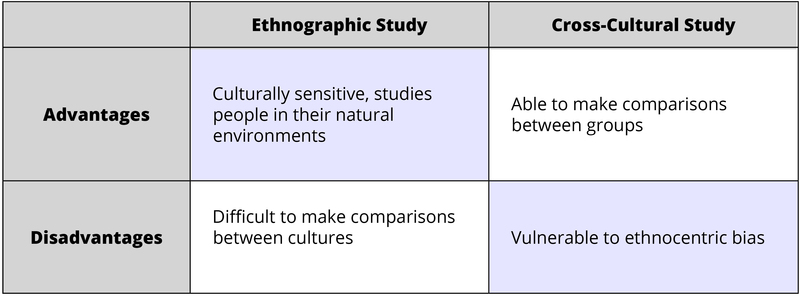

Cultural psychology is distinct from cross-cultural psychology, and this can be confusing. Cross-cultural studiesare those that use standard forms of measurement, such as Likert scales, to compare people from different cultures and identify their differences. Both cultural and cross-cultural studies have their own advantages and disadvantages (see Table 1).

Interestingly, researchers—and the rest of us!—have as much to learn from cultural similarities as cultural differences, and both require comparisons across cultures. For example, Diener and Oishi (2000) were interested in exploring the relationship between money and happiness. They were specifically interested in cross-cultural differences in levels of life satisfaction between people from different cultures. To examine this question they used international surveys that asked all participants the exact same question, such as “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” and used a standard scale for answers; in this case one that asked people to use a 1-10 scale to respond. They also collected data on average income levels in each nation, and adjusted these for local differences in how many goods and services that money can buy.

The Diener research team discovered that, across more than 40 nations there was a tendency for money to be associated with higher life satisfaction. People from richer countries such as Denmark, Switzerland and Canada had relatively high satisfaction while their counterparts from poorer countries such as India and Belarus had lower levels. There were some interesting exceptions, however. People from Japan—a wealthy nation—reported lower satisfaction than did their peers in nations with similar wealth. In addition, people from Brazil—a poorer nation—had unusually high scores compared to their income counterparts.

One problem with cross-cultural studies is that they are vulnerable to ethnocentric bias. This means that the researcher who designs the study might be influenced by personal biases that could affect research outcomes—without even being aware of it. For example, a study on happiness across cultures might investigate the ways that personal freedom is associated with feeling a sense of purpose in life. The researcher might assume that when people are free to choose their own work and leisure, they are more likely to pick options they care deeply about. Unfortunately, this researcher might overlook the fact that in much of the world it is considered important to sacrifice some personal freedom in order to fulfill one’s duty to the group (Triandis, 1995). Because of the danger of this type of bias, social psychologists must continue to improve their methodology.

What is Culture?

Defining Culture

Like the words “happiness” and “intelligence,” the word “culture” can be tricky to define. Culture is a word that suggests social patterns of shared meaning. In essence, it is a collective understanding of the way the world works, shared by members of a group and passed down from one generation to the next. For example, members of the Yanomamö tribe, in South America, share a cultural understanding of the world that includes the idea that there are four parallel levels to reality that include an abandoned level, and earthly level and heavenly and hell-like levels. Similarly, members of surfing culture understand their athletic pastime as being worthwhile and governed by formal rules of etiquette known only to insiders. There are several features of culture that are central to understanding the uniqueness and diversity of the human mind:

- Versatility: Culture can change and adapt. Someone from the state of Orissa, in India, for example, may have multiple identities. She might see herself as Oriya when at home and speaking her native language. At other times, such as during the national cricket match against Pakistan, she might consider herself Indian. This is known as situational identity.

- Sharing: Culture is the product of people sharing with one another. Humans cooperate and share knowledge and skills with other members of their networks. The ways they share, and the content of what they share, helps make up culture. Older adults, for instance, remember a time when long-distance friendships were maintained through letters that arrived in the mail every few months. Contemporary youth culture accomplishes the same goal through the use of instant text messages on smart phones.

- Accumulation: Cultural knowledge is cumulative. That is, information is “stored.” This means that a culture’s collective learning grows across generations. We understand more about the world today than we did 200 years ago, but that doesn’t mean the culture from long ago has been erased by the new. For instance, members of the Haida culture—a First Nations people in British Columbia, Canada—profit from both ancient and modern experiences. They might employ traditional fishing practices and wisdom stories while also using modern technologies and services.

- Patterns: There are systematic and predictable ways of behavior or thinking across members of a culture. Patterns emerge from adapting, sharing, and storing cultural information. Patterns can be both similar and different across cultures. For example, in both Canada and India it is considered polite to bring a small gift to a host’s home. In Canada, it is more common to bring a bottle of wine and for the gift to be opened right away. In India, by contrast, it is more common to bring sweets, and often the gift is set aside to be opened later.

Understanding the changing nature of culture is the first step toward appreciating how it helps people. The concept of cultural intelligence is the ability to understand why members of other cultures act in the ways they do. Rather than dismissing foreign behaviors as weird, inferior, or immoral, people high in cultural intelligence can appreciate differences even if they do not necessarily share another culture’s views or adopt its ways of doing things.

Thinking about Culture

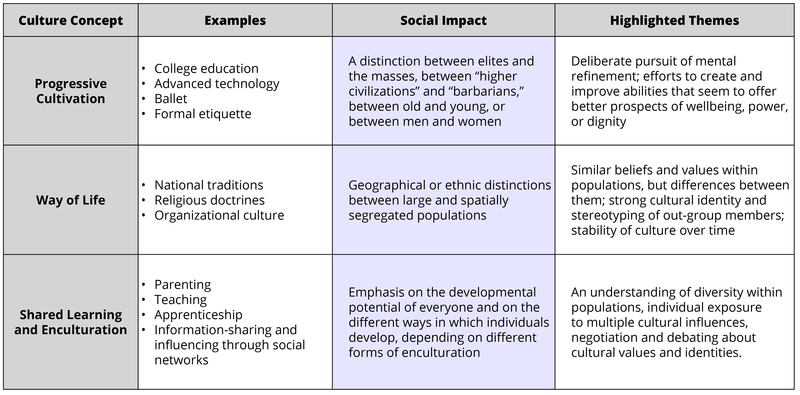

One of the biggest problems with understanding culture is that the word itself is used in different ways by different people. When someone says, “My company has a competitive culture,” does it mean the same thing as when another person says, “I’m taking my children to the museum so they can get some culture”? The truth is, there are many ways to think about culture. Here are three ways to parse this concept:

- Progressive cultivation: This refers to a relatively small subset of activities that are intentional and aimed at “being refined.” Examples include learning to play a musical instrument, appreciating visual art, and attending theater performances, as well as other instances of so-called “high art.” This was the predominant use of the word culture through the mid-19th century. This notion of culture formed the basis, in part, of a superior mindset on the behalf of people from the upper economic classes. For instance, many tribal groups were seen as lacking cultural sophistication under this definition. In the late 19th century, as global travel began to rise, this understanding of culture was largely replaced with an understanding of it as a way of life.

- Ways of Life: This refers to distinct patterns of beliefs and behaviors widely shared among members of a culture. The “ways of life” understanding of culture shifts the emphasis to patterns of belief and behavior that persist over many generations. Although cultures can be small—such as “school culture”—they usually describe larger populations, such as nations. People occasionally confuse national identity with culture. There are similarities in culture between Japan, China, and Korea, for example, even though politically they are very different. Indeed, each of these nations also contains a great deal of cultural variation within themselves.

- Shared Learning: In the 20th century, anthropologists and social psychologists developed the concept of enculturation to refer to the ways people learn about and shared cultural knowledge. Where “ways of life” is treated as a noun “enculturation” is a verb. That is, enculturation is a fluid and dynamic process. That is, it emphasizes that culture is a process that can be learned. As children are raised in a society, they are taught how to behave according to regional cultural norms. As immigrants settle in a new country, they learn a new set of rules for behaving and interacting. In this way, it is possible for a person to have multiple cultural scripts.

The understanding of culture as a learned pattern of views and behaviors is interesting for several reasons. First, it highlights the ways groups can come into conflict with one another. Members of different cultures simply learn different ways of behaving. Modern youth culture, for instance, interacts with technologies such as smart phones using a different set of rules than people who are in their 40s, 50s, or 60s. Older adults might find texting in the middle of a face-to-face conversation rude while younger people often do not. These differences can sometimes become politicized and a source of tension between groups. One example of this is Muslim women who wear a hijab, or head scarf. Non-Muslims do not follow this practice, so occasional misunderstandings arise about the appropriateness of the tradition. Second, understanding that culture is learned is important because it means that people can adopt an appreciation of patterns of behavior that are different than their own. For example, non-Muslims might find it helpful to learn about the hijab. Where did this tradition come from? What does it mean and what are various Muslim opinions about wearing one? Finally, understanding that culture is learned can be helpful in developing self-awareness. For instance, people from the United States might not even be aware of the fact that their attitudes about public nudity are influenced by their cultural learning. While women often go topless on beaches in Europe and women living a traditional tribal existence in places like the South Pacific also go topless, it is illegal for women in some of the United States to do so. These cultural norms for modesty—reflected in government laws and policies– also enter the discourse on social issues such as the appropriateness of breast-feeding in public. Understanding that your preferences are—in many cases—the products of cultural learning might empower you to revise them if doing so will lead to a better life for you or others.

The Self and Culture

Traditionally, social psychologists have thought about how patterns of behavior have an overarching effect on populations’ attitudes. Harry Triandis, a cross-cultural psychologist, has studied culture in terms of individualism and collectivism. Triandis became interested in culture because of his unique upbringing. Born in Greece, he was raised under both the German and Italian occupations during World War II. The Italian soldiers broadcast classical music in the town square and built a swimming pool for the townspeople. Interacting with these foreigners—even though they were an occupying army—sparked Triandis’ curiosity about other cultures. He realized that he would have to learn English if he wanted to pursue academic study outside of Greece and so he practiced with the only local who knew the language: a mentally ill 70 year old who was incarcerated for life at the local hospital. He went on to spend decades studying the ways people in different cultures define themselves (Triandis, 2008).

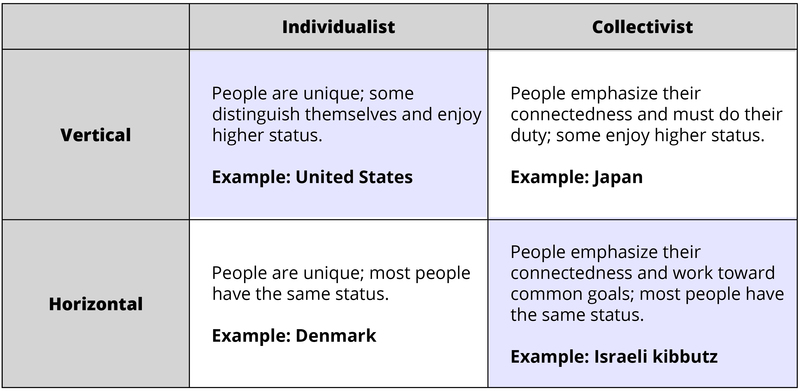

So, what exactly were these two patterns of culture Triandis focused on: individualism and collectivism? Individualists, such as most people born and raised in Australia or the United States, define themselves as individuals. They seek personal freedom and prefer to voice their own opinions and make their own decisions. By contrast, collectivists—such as most people born and raised in Korea or in Taiwan— are more likely to emphasize their connectedness to others. They are more likely to sacrifice their personal preferences if those preferences come in conflict with the preferences of the larger group (Triandis, 1995).

Both individualism and collectivism can further be divided into vertical and horizontal dimensions (Triandis, 1995). Essentially, these dimensions describe social status among members of a society. People in vertical societies differ in status, with some people being more highly respected or having more privileges, while in horizontal societies people are relatively equal in status and privileges. These dimensions are, of course, simplifications.

Neither individualism nor collectivism is the “correct way to live.” Rather, they are two separate patterns with slightly different emphases. People from individualistic societies often have more social freedoms, while collectivistic societies often have better social safety nets.

There are yet other ways of thinking about culture, as well. The cultural patterns of individualism and collectivism are linked to an important psychological phenomenon: the way that people understand themselves. Known as self-construal, this is the way people define the way they “fit” in relation to others. Individualists are more likely to define themselves in terms of an independent self. This means that people see themselves as A) being a unique individual with a stable collection of personal traits, and B) that these traits drive behavior. By contrast, people from collectivist cultures are more likely to identify with the interdependent self. This means that people see themselves as A) defined differently in each new social context and B) social context, rather than internal traits, are the primary drivers of behavior (Markus & Kitiyama, 1991).

What do the independent and interdependent self look like in daily life? One simple example can be seen in the way that people describe themselves. Imagine you had to complete the sentence starting with “I am…..”. And imagine that you had to do this 10 times. People with an independent sense of self are more likely to describe themselves in terms of traits such as “I am honest,” “I am intelligent,” or “I am talkative.” On the other hand, people with a more interdependent sense of self are more likely to describe themselves in terms of their relation to others such as “I am a sister,” “I am a good friend,” or “I am a leader on my team” (Markus, 1977).

The psychological consequences of having an independent or interdependent self can also appear in more surprising ways. Take, for example, the emotion of anger. In Western cultures, where people are more likely to have an independent self, anger arises when people’s personal wants, needs, or values are attacked or frustrated (Markus & Kitiyama, 1994). Angry Westerners sometimes complain that they have been “treated unfairly.” Simply put, anger—in the Western sense—is the result of violations of the self. By contrast, people from interdependent self cultures, such as Japan, are likely to experience anger somewhat differently. They are more likely to feel that anger is unpleasant not because of some personal insult but because anger represents a lack of harmony between people. In this instance, anger is particularly unpleasant when it interferes with close relationships.

Culture is Learned

It’s important to understand that culture is learned. People aren’t born using chopsticks or being good at soccer simply because they have a genetic predisposition for it. They learn to excel at these activities because they are born in countries like Argentina, where playing soccer is an important part of daily life, or in countries like Taiwan, where chopsticks are the primary eating utensils. So, how are such cultural behaviors learned? It turns out that cultural skills and knowledge are learned in much the same way a person might learn to do algebra or knit. They are acquired through a combination of explicit teaching and implicit learning—by observing and copying.

Cultural teaching can take many forms. It begins with parents and caregivers, because they are the primary influence on young children. Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thankyou.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture. They introduce children to religious beliefs and the rituals that go with them. They even teach children how to think and feel! Adult men, for example, often exhibit a certain set of emotional expressions—such as being tough and not crying—that provides a model of masculinity for their children. This is why we see different ways of expressing the same emotions in different parts of the world.

In some societies, it is considered appropriate to conceal anger. Instead of expressing their feelings outright, people purse their lips, furrow their brows, and say little. In other cultures, however, it is appropriate to express anger. In these places, people are more likely to bare their teeth, furrow their brows, point or gesture, and yell (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Chung, 2010). Such patterns of behavior are learned. Often, adults are not even aware that they are, in essence, teaching psychology—because the lessons are happening through observational learning.

Let’s consider a single example of a way you behave that is learned, which might surprise you. All people gesture when they speak. We use our hands in fluid or choppy motions—to point things out, or to pantomime actions in stories. Consider how you might throw your hands up and exclaim, “I have no idea!” or how you might motion to a friend that it’s time to go. Even people who are born blind use hand gestures when they speak, so to some degree this is a universal behavior, meaning all people naturally do it. However, social researchers have discovered that culture influences how a person gestures. Italians, for example, live in a society full of gestures. In fact, they use about 250 of them (Poggi, 2002)! Some are easy to understand, such as a hand against the belly, indicating hunger. Others, however, are more difficult. For example, pinching the thumb and index finger together and drawing a line backwards at face level means “perfect,” while knocking a fist on the side of one’s head means “stubborn.”

Beyond observational learning, cultures also use rituals to teach people what is important. For example, young people who are interested in becoming Buddhist monks often have to endure rituals that help them shed feelings of specialness or superiority—feelings that run counter to Buddhist doctrine. To do this, they might be required to wash their teacher’s feet, scrub toilets, or perform other menial tasks. Similarly, many Jewish adolescents go through the process of bar and bat mitzvah. This is a ceremonial reading from scripture that requires the study of Hebrew and, when completed, signals that the youth is ready for full participation in public worship.

Cultural Relativism

When social psychologists research culture, they try to avoid making value judgments. This is known as value-free research and is considered an important approach to scientific objectivity. But, while such objectivity is the goal, it is a difficult one to achieve. With this in mind, anthropologists have tried to adopt a sense of empathy for the cultures they study. This has led to cultural relativism, the principle of regarding and valuing the practices of a culture from the point of view of that culture. It is a considerate and practical way to avoid hasty judgments. Take for example, the common practice of same-sex friends in India walking in public while holding hands: this is a common behavior and a sign of connectedness between two people. In England, by contrast, holding hands is largely limited to romantically involved couples, and often suggests a sexual relationship. These are simply two different ways of understanding the meaning of holding hands. Someone who does not take a relativistic view might be tempted to see their own understanding of this behavior as superior and, perhaps, the foreign practice as being immoral.

Despite the fact that cultural relativism promotes the appreciation for cultural differences, it can also be problematic. At its most extreme it leaves no room for criticism of other cultures, even if certain cultural practices are horrific or harmful. Many practices have drawn criticism over the years. In Madagascar, for example, the famahidana funeral tradition includes bringing bodies out from tombs once every seven years, wrapping them in cloth, and dancing with them. Some people view this practice as disrespectful to the body of a deceased person. Another example can be seen in the historical Indian practice of sati—the burning to death of widows on their deceased husband’s funeral pyre. This practice was outlawed by the British when they colonized India. Today, a debate rages about the ritual cutting of genitals of children in several Middle Eastern and African cultures. To a lesser extent, this same debate arises around the circumcision of baby boys in Western hospitals. When considering harmful cultural traditions, it can be patronizing to the point of racism to use cultural relativism as an excuse for avoiding debate. To assume that people from other cultures are neither mature enough nor responsible enough to consider criticism from the outside is demeaning.

Positive cultural relativism is the belief that the world would be a better place if everyone practiced some form of intercultural empathy and respect. This approach offers a potentially important contribution to theories of cultural progress: to better understand human behavior, people should avoid adopting extreme views that block discussions about the basic morality or usefulness of cultural practices.

Conclusion

We live in a unique moment in history. We are experiencing the rise of a global culture in which people are connected and able to exchange ideas and information better than ever before. International travel and business are on the rise. Instantaneous communication and social media are creating networks of contacts who would never otherwise have had a chance to connect. Education is expanding, music and films cross national borders, and state-of-the-art technology affects us all. In this world, an understanding of what culture is and how it happens, can set the foundation for acceptance of differences and respectful disagreements. The science of social psychology—along with the other culture-focused sciences, such as anthropology and sociology—can help produce insights into cultural processes. These insights, in turn, can be used to increase the quality of intercultural dialogue, to preserve cultural traditions, and to promote self-awareness.

Outside Resources

- Web: A collection of links on the topic of peace psychology

- https://www.socialpsychology.org/peace.htm

- Web: A great resource for all things social psychology, all in one place – Social Psychology Network

- http://www.socialpsychology.org/

- Web: A list of profiles of major historical figures in social psychology

- https://www.socialpsychology.org/social-figures.htm

- Web: A review of the history of social psychology as well as the topics of interest in the field

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_psychology

- Web: A succinct review of major historical figures in social psychology

- http://www.simplypsychology.org/social-psychology.html

- Web: An article on the definition and areas of influence of peace psychology

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peace_psychology

- Web: Article describing another way of conceptualizing levels of analysis in social psychology

- http://psych.colorado.edu/~oreilly/cecn/node11.html

- Web: Extended list of major historical figures in social psychology

- http://www.sparknotes.com/psychology/psych101/majorfigures/characters.html

- Web: History and principles of social psychology

- https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/defining-social-psychology-history-and-principles/

- Web: Links to sources on history of social psychology as well as major historical figures

- https://www.socialpsychology.org/history.htm

- Web: The Society for the Study of Peace, Conflict and Violence

- http://www.peacepsych.org/

- Articles: International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology (IACCP) [Wolfgang Friedlmeier, ed] Online Readings in Psychology and Culture (ORPC)

- http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/orpc/

- Database: Human Relations Area Files (HRAF) ‘World Cultures’ database

- http://hraf.yale.edu/

- Organization: Plous, Scott, et al, Social Psychology Network, Cultural Psychology Links by Subtopic

- https://www.socialpsychology.org/cultural.htm

- Study: Hofstede, Geert et al, The Hofstede Center: Strategy, Culture, Change

- http://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html

Discussion Questions

- List the types of relationships you have. How do these people affect your behavior? Are there actions you perform or things you do that you might not otherwise if it weren’t for them?

- When you think about where each person in your psychology class sits, what influences the seat he or she chooses to use? Is it just a matter of personal preference or are there other influences at work?

- Do you ever try to persuade friends or family members to do something? How do you try to persuade them? How do they try to persuade you? Give specific examples.

- If you were a social psychologist, what would you want to research? Why? How would you go about it?

- How do you think the culture you live in is similar to or different from the culture your parents were raised in?

- What are the risks of associating “culture” mainly with differences between large populations such as entire nations?

- If you were a social psychologist, what steps would you take to guard against ethnocentricity in your research?

- Name one value that is important to you. How did you learn that value?

- In your opinion, has the internet increased or reduced global cultural diversity?

- Imagine a social psychologist who researches the culture of extremely poor people, such as so-called “rag pickers,” who sort through trash for food or for items to sell. What ethical challenges can you identify in this type of study?

Vocabulary

- Attitude

- A way of thinking or feeling about a target that is often reflected in a person’s behavior. Examples of attitude targets are individuals, concepts, and groups.

- Attraction

- The psychological process of being sexually interested in another person. This can include, for example, physical attraction, first impressions, and dating rituals.

- Blind to the research hypothesis

- When participants in research are not aware of what is being studied.

- Conformity

- Changing one’s attitude or behavior to match a perceived social norm.

- Culture of honor

- A culture in which personal or family reputation is especially important.

- Discrimination

- Discrimination is behavior that advantages or disadvantages people merely based on their group membership.

- Fundamental attribution error

- The tendency to emphasize another person’s personality traits when describing that person’s motives and behaviors and overlooking the influence of situational factors.

- Hypothesis

- A possible explanation that can be tested through research.

- Levels of analysis

- Complementary views for analyzing and understanding a phenomenon.

- Need to belong

- A strong natural impulse in humans to form social connections and to be accepted by others.

- Obedience

- Responding to an order or command from a person in a position of authority.

- Observational learning

- Learning by observing the behavior of others.

- Prejudice

- An evaluation or emotion toward people based merely on their group membership.

- Reciprocity

- The act of exchanging goods or services. By giving a person a gift, the principle of reciprocity can be used to influence others; they then feel obligated to give back.

- Research confederate

- A person working with a researcher, posing as a research participant or as a bystander.

- Research participant

- A person being studied as part of a research program.

- The way a person explains the motives or behaviors of others.

- The way people process and apply information about others.

- When one person causes a change in attitude or behavior in another person, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

- The branch of psychological science that is mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Stereotyping

- A mental process of using information shortcuts about a group to effectively navigate social situations or make decisions.

- Stigmatized group

- A group that suffers from social disapproval based on some characteristic that sets them apart from the majority.

- Collectivism

- The cultural trend in which the primary unit of measurement is the group. Collectivists are likely to emphasize duty and obligation over personal aspirations.

- Cross-cultural psychology (or cross-cultural studies)

- An approach to researching culture that emphasizes the use of standard scales as a means of making meaningful comparisons across groups.

- Cross-cultural studies (or cross-cultural psychology)

- An approach to researching culture that emphasizes the use of standard scales as a means of making meaningful comparisons across groups.

- Cultural differences

- An approach to understanding culture primarily by paying attention to unique and distinctive features that set them apart from other cultures.

- Cultural intelligence

- The ability and willingness to apply cultural awareness to practical uses.

- Cultural psychology

- An approach to researching culture that emphasizes the use of interviews and observation as a means of understanding culture from its own point of view.

- Cultural relativism

- The principled objection to passing overly culture-bound (i.e., “ethnocentric”) judgements on aspects of other cultures.

- Cultural script

- Learned guides for how to behave appropriately in a given social situation. These reflect cultural norms and widely accepted values.

- Cultural similarities

- An approach to understanding culture primarily by paying attention to common features that are the same as or similar to those of other cultures

- Culture

- A pattern of shared meaning and behavior among a group of people that is passed from one generation to the next.

- Enculturation

- The uniquely human form of learning that is taught by one generation to another.

- Ethnocentric bias (or ethnocentrism)

- Being unduly guided by the beliefs of the culture you’ve grown up in, especially when this results in a misunderstanding or disparagement of unfamiliar cultures.

- Ethnographic studies

- Research that emphasizes field data collection and that examines questions that attempt to understand culture from it’s own context and point of view.

- Independent self

- The tendency to define the self in terms of stable traits that guide behavior.

- Individualism

- The cultural trend in which the primary unit of measurement is the individual. Individualists are likely to emphasize uniqueness and personal aspirations over social duty.

- Interdependent self

- The tendency to define the self in terms of social contexts that guide behavior.

- Observational learning

- Learning by observing the behavior of others.

- Open ended questions

- Research questions that ask participants to answer in their own words.

- Ritual

- Rites or actions performed in a systematic or prescribed way often for an intended purpose. Example: The exchange of wedding rings during a marriage ceremony in many cultures.

- Self-construal

- The extent to which the self is defined as independent or as relating to others.

- Situational identity

- Being guided by different cultural influences in different situations, such as home versus workplace, or formal versus informal roles.

- Standard scale

- Research method in which all participants use a common scale—typically a Likert scale—to respond to questions.

- Value judgment

- An assessment—based on one’s own preferences and priorities—about the basic “goodness” or “badness” of a concept or practice.

- Value-free research

- Research that is not influenced by the researchers’ own values, morality, or opinions.

References

- Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., … & Highberger, L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 105-118.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497-529.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An” experimental ethnography.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 945-960.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81-84.

- Holmes T. H. & Rahe R.H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2): 213–218.

- Pavot, W., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1990). Extraversion and happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 1299-1306.

- Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2013). Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 1-10.

- Strohmetz, D. B., Rind, B., Fisher, R., & Lynn, M. (2002). Sweetening the till: The use of candy to increase restaurant tipping. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(2), 300-309.

- Wirtz, D., Biswas-Diener, R., Diener, E., & Drogos, K.L. (2011). The friendship effect in judgments of physical attractiveness. In J. C. Toller (Ed.), Friendships: Types, cultural, psychological and social aspects (pp. 145-162). Hauppage, NY: Nova.

- Diener, E. & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E.M. Suh (Eds), Culture and subjective well-being, Cambrdige, MA: MIT Press.

- Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 63-78.

- Markus, H. & Kitiyama, S (1994).The cultural construction of self and emotion: Implications for social behavior. In S. Kitiyama & H. Markus (Eds), Emotion and Culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Markus, H. & Kitiyama, S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

- Markus, H., Ryff, C., Curhan, K. & Palmersheim, K. (2004). In their own words: Well-being at midlife among high school and college educated adults. In O.G. Brim & C. Ryff (Eds), How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Chung, J. (2010). The expression of anger across cultures. In M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, G., and C. Spielberger (Eds.) International handbook of anger (pp.125-137). New York, NY: Springer

- Poggi, I. (2002). Towards the alphabet and the lexicon of gesture, gaze and touch. In Virtual Symposium on Multimodality of Human Communication. Retrieved from http://www.semioticon.com/virtuals/multimodality/geyboui41.pdf

- Triandis, H. C. (2008). An autobiography: Why did culture shape my career. R. Levine, A. Rodrigues & L. Zelezny, L. (Eds.). Journeys in social psychology: Looking back to inspire the future. (pp.145-164). New York, NY: Taylor And Francis.

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview press.

Authors

Robert Biswas-Diener

Robert Biswas-DienerDr. Robert Biswas-Diener is a part-time instructor at Portland State University and is senior editor of Noba. He has more than 50 publications on happiness and other positive topics in peer-reviewed journals. He is author of The Upside of Your Dark Side.

Neil Thin

Neil ThinNeil Thin is a Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh. He also has more than 30 years’ experience social planning in over 20 countries worldwide, in which work he has specialized in the pursuit of aspirational and culturally flexible ways of promoting social goods rather than merely reducing social harms. He has authored books on poverty reduction, social forestry, social progress, and social happiness.

-

Creative Commons License

Culture by Robert Biswas-Diener and Neil Thin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Culture by Robert Biswas-Diener and Neil Thin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Creative Commons License

An Introduction to the Science of Social Psychology by Robert Biswas-Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

An Introduction to the Science of Social Psychology by Robert Biswas-Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.