Contents

- 1 Social and Personality Development in Childhood

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Relationships

- 4 Social Understanding

- 5 Personality

- 6 Social and Emotional Competence

- 7 Conclusion

- 8 Attachment Through the Life Course

- 9 Introduction

- 10 Attachment Theory: A Brief History and Core Concepts

- 11 Individual Differences in Infant Attachment

- 12 Antecedents of Attachment Patterns

- 13 Attachment Patterns and Child Outcomes

- 14 Attachment in Adulthood

Social and Personality Development in Childhood

University of California, Davis

Childhood social and personality development emerges through the interaction of social influences, biological maturation, and the child’s representations of the social world and the self. This interaction is illustrated in a discussion of the influence of significant relationships, the development of social understanding, the growth of personality, and the development of social and emotional competence in childhood.

Learning Objectives

- Provide specific examples of how the interaction of social experience, biological maturation, and the child’s representations of experience and the self provide the basis for growth in social and personality development.

- Describe the significant contributions of parent–child and peer relationships to the development of social skills and personality in childhood.

- Explain how achievements in social understanding occur in childhood. Moreover, do scientists believe that infants and young children are egocentric?

- Describe the association of temperament with personality development.

- Explain what is “social and emotional competence“ and provide some examples of how it develops in childhood.

Introduction

“How have I become the kind of person I am today?” Every adult ponders this question from time to time. The answers that readily come to mind include the influences of parents, peers, temperament, a moral compass, a strong sense of self, and sometimes critical life experiences such as parental divorce. Social and personality development encompasses these and many other influences on the growth of the person. In addition, it addresses questions that are at the heart of understanding how we develop as unique people. How much are we products of nature or nurture? How enduring are the influences of early experiences? The study of social and personality development offers perspective on these and other issues, often by showing how complex and multifaceted are the influences on developing children, and thus the intricate processes that have made you the person you are today (Thompson, 2006a).

Understanding social and personality development requires looking at children from three perspectives that interact to shape development. The first is the social context in which each child lives, especially the relationships that provide security, guidance, and knowledge. The second is biological maturation that supports developing social and emotional competencies and underlies temperamental individuality. The third is children’s developing representations of themselves and the social world. Social and personality development is best understood as the continuous interaction between these social, biological, and representational aspects of psychological development.

Relationships

This interaction can be observed in the development of the earliest relationships between infants and their parents in the first year. Virtually all infants living in normal circumstances develop strong emotional attachments to those who care for them. Psychologists believe that the development of these attachments is as biologically natural as learning to walk and not simply a byproduct of the parents’ provision of food or warmth. Rather, attachments have evolved in humans because they promote children’s motivation to stay close to those who care for them and, as a consequence, to benefit from the learning, security, guidance, warmth, and affirmation that close relationships provide (Cassidy, 2008).

Although nearly all infants develop emotional attachments to their caregivers–parents, relatives, nannies– their sense of security in those attachments varies. Infants become securely attached when their parents respond sensitively to them, reinforcing the infants’ confidence that their parents will provide support when needed. Infants become insecurely attached when care is inconsistent or neglectful; these infants tend to respond avoidantly, resistantly, or in a disorganized manner (Belsky & Pasco Fearon, 2008). Such insecure attachments are not necessarily the result of deliberately bad parenting but are often a byproduct of circumstances. For example, an overworked single mother may find herself overstressed and fatigued at the end of the day, making fully-involved childcare very difficult. In other cases, some parents are simply poorly emotionally equipped to take on the responsibility of caring for a child.

The different behaviors of securely- and insecurely-attached infants can be observed especially when the infant needs the caregiver’s support. To assess the nature of attachment, researchers use a standard laboratory procedure called the “Strange Situation,” which involves brief separations from the caregiver (e.g., mother) (Solomon & George, 2008). In the Strange Situation, the caregiver is instructed to leave the child to play alone in a room for a short time, then return and greet the child while researchers observe the child’s response. Depending on the child’s level of attachment, he or she may reject the parent, cling to the parent, or simply welcome the parent—or, in some instances, react with an agitated combination of responses.

Infants can be securely or insecurely attached with mothers, fathers, and other regular caregivers, and they can differ in their security with different people. The security of attachment is an important cornerstone of social and personality development, because infants and young children who are securely attached have been found to develop stronger friendships with peers, more advanced emotional understanding and early conscience development, and more positive self-concepts, compared with insecurely attached children (Thompson, 2008). This is consistent with attachment theory’s premise that experiences of care, resulting in secure or insecure attachments, shape young children’s developing concepts of the self, as well as what people are like, and how to interact with them.

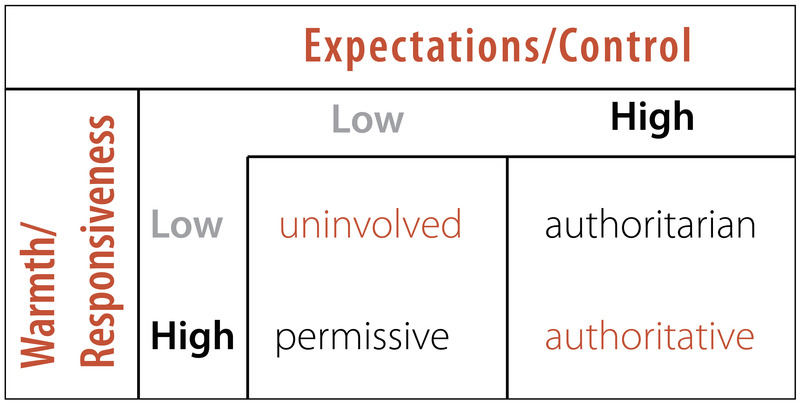

As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships. In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high (but reasonable) expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm and responsive, and use reasoning (rather than coercion) as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior. This kind of parenting style has been described as authoritative (Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. By contrast, some less-constructive parent-child relationships result from authoritarian, uninvolved, or permissive parenting styles (see Table 1).

Parental roles in relation to their children change in other ways, too. Parents increasingly become mediators (or gatekeepers) of their children’s involvement with peers and activities outside the family. Their communication and practice of values contributes to children’s academic achievement, moral development, and activity preferences. As children reach adolescence, the parent-child relationship increasingly becomes one of “coregulation,” in which both the parent(s) and the child recognizes the child’s growing competence and autonomy, and together they rebalance authority relations. We often see evidence of this as parents start accommodating their teenage kids’ sense of independence by allowing them to get cars, jobs, attend parties, and stay out later.

Family relationships are significantly affected by conditions outside the home. For instance, the Family Stress Model describes how financial difficulties are associated with parents’ depressed moods, which in turn lead to marital problems and poor parenting that contributes to poorer child adjustment (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Within the home, parental marital difficulty or divorce affects more than half the children growing up today in the United States. Divorce is typically associated with economic stresses for children and parents, the renegotiation of parent-child relationships (with one parent typically as primary custodian and the other assuming a visiting relationship), and many other significant adjustments for children. Divorce is often regarded by children as a sad turning point in their lives, although for most it is not associated with long-term problems of adjustment (Emery, 1999).

Peer Relationships

Parent-child relationships are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Peer relationships are also important. Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as infants, children get their first encounter with sharing (of each other’s toys); during pretend play as preschoolers they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories; and in primary school, they may join a sports team, learning to work together and support each other emotionally and strategically toward a common goal. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents.

However, peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Bowker, & McDonald, 2011). Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. For example, a boy who is not athletic may feel unworthy of his football-playing peers and revert to shy behavior, isolating himself and avoiding conversation. Conversely, an athlete who doesn’t “get” Shakespeare may feel embarrassed and avoid reading altogether. Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal)—which significantly affects a child’s outlook on the world. Each of these aspects of peer relationships requires developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept.

Social Understanding

As we have seen, children’s experience of relationships at home and the peer group contributes to an expanding repertoire of social and emotional skills and also to broadened social understanding. In these relationships, children develop expectations for specific people (leading, for example, to secure or insecure attachments to parents), understanding of how to interact with adults and peers, and developing self-concept based on how others respond to them. These relationships are also significant forums for emotional development.

Remarkably, young children begin developing social understanding very early in life. Before the end of the first year, infants are aware that other people have perceptions, feelings, and other mental states that affect their behavior, and which are different from the child’s own mental states. This can be readily observed in a process called social referencing, in which an infant looks to the mother’s face when confronted with an unfamiliar person or situation (Feinman, 1992). If the mother looks calm and reassuring, the infant responds positively as if the situation is safe. If the mother looks fearful or distressed, the infant is likely to respond with wariness or distress because the mother’s expression signals danger. In a remarkably insightful manner, therefore, infants show an awareness that even though they are uncertain about the unfamiliar situation, their mother is not, and that by “reading” the emotion in her face, infants can learn about whether the circumstance is safe or dangerous, and how to respond.

Although developmental scientists used to believe that infants are egocentric—that is, focused on their own perceptions and experience—they now realize that the opposite is true. Infants are aware at an early stage that people have different mental states, and this motivates them to try to figure out what others are feeling, intending, wanting, and thinking, and how these mental states affect their behavior. They are beginning, in other words, to develop a theory of mind, and although their understanding of mental states begins very simply, it rapidly expands (Wellman, 2011). For example, if an 18-month-old watches an adult try repeatedly to drop a necklace into a cup but inexplicably fail each time, they will immediately put the necklace into the cup themselves—thus completing what the adult intended, but failed, to do. In doing so, they reveal their awareness of the intentions underlying the adult’s behavior (Meltzoff, 1995). Carefully designed experimental studies show that by late in the preschool years, young children understand that another’s beliefs can be mistaken rather than correct, that memories can affect how you feel, and that one’s emotions can be hidden from others (Wellman, 2011). Social understanding grows significantly as children’s theory of mind develops.

How do these achievements in social understanding occur? One answer is that young children are remarkably sensitive observers of other people, making connections between their emotional expressions, words, and behavior to derive simple inferences about mental states (e.g., concluding, for example, that what Mommy is looking at is in her mind) (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 2001). This is especially likely to occur in relationships with people whom the child knows well, consistent with the ideas of attachment theory discussed above. Growing language skills give young children words with which to represent these mental states (e.g., “mad,” “wants”) and talk about them with others. Thus in conversation with their parents about everyday experiences, children learn much about people’s mental states from how adults talk about them (“Your sister was sad because she thought Daddy was coming home.”) (Thompson, 2006b). Developing social understanding is, in other words, based on children’s everyday interactions with others and their careful interpretations of what they see and hear. There are also some scientists who believe that infants are biologically prepared to perceive people in a special way, as organisms with an internal mental life, and this facilitates their interpretation of people’s behavior with reference to those mental states (Leslie, 1994).

Personality

Parents look into the faces of their newborn infants and wonder, “What kind of person will this child will become?” They scrutinize their baby’s preferences, characteristics, and responses for clues of a developing personality. They are quite right to do so, because temperament is a foundation for personality growth. But temperament (defined as early-emerging differences in reactivity and self-regulation) is not the whole story. Although temperament is biologically based, it interacts with the influence of experience from the moment of birth (if not before) to shape personality (Rothbart, 2011). Temperamental dispositions are affected, for example, by the support level of parental care. More generally, personality is shaped by the goodness of fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and characteristics of the environment (Chess & Thomas, 1999). For example, an adventurous child whose parents regularly take her on weekend hiking and fishing trips would be a good “fit” to her lifestyle, supporting personality growth. Personality is the result, therefore, of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience, as is true for many other aspects of social and personality development.

Personality develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics emerge and change over time. A newborn is not capable of much self-control, but as brain-based capacities for self-control advance, temperamental changes in self-regulation become more apparent. For example, a newborn who cries frequently doesn’t necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to cry.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, and many other qualities are encompassed into personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics.

Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that parents gazed upon thus becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance.

Social and Emotional Competence

Social and personality development is built from the social, biological, and representational influences discussed above. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society: a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (helping, caring, sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them. These are some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence.

These achievements of social and personality development derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development. Conscience consists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internal standards of conduct (Kochanska, 2002). Conscience emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation (a quality called effortful control) than are others, while some children are dispositionally more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. Conscience development grows through a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and how parents communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations. Moreover, as an illustration of the interaction of genes and experience, one research group found that young children with a particular gene allele (the 5-HTTLPR) were low on measures of conscience development when they had previously experienced unresponsive maternal care, but children with the same allele growing up with responsive care showed strong later performance on conscience measures (Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011).

Conscience development also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent in a manner that provides a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012).

The development of gender and gender identity is likewise an interaction among social, biological, and representational influences (Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Young children learn about gender from parents, peers, and others in society, and develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness (called gender schemas). They also negotiate biological transitions (such as puberty) that cause their sense of themselves and their sexual identity to mature.

Each of these examples of the growth of social and emotional competence illustrates not only the interaction of social, biological, and representational influences, but also how their development unfolds over an extended period. Early influences are important, but not determinative, because the capabilities required for mature moral conduct, gender identity, and other outcomes continue to develop throughout childhood, adolescence, and even the adult years.

Conclusion

As the preceding sentence suggests, social and personality development continues through adolescence and the adult years, and it is influenced by the same constellation of social, biological, and representational influences discussed for childhood. Changing social relationships and roles, biological maturation and (much later) decline, and how the individual represents experience and the self continue to form the bases for development throughout life. In this respect, when an adult looks forward rather than retrospectively to ask, “what kind of person am I becoming?”—a similarly fascinating, complex, multifaceted interaction of developmental processes lies ahead.

Attachment Through the Life Course

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The purpose of this module is to provide a brief review of attachment theory—a theory designed to explain the significance of the close, emotional bonds that children develop with their caregivers and the implications of those bonds for understanding personality development. The module discusses the origins of the theory, research on individual differences in attachment security in infancy and childhood, and the role of attachment in adult relationships.

Learning Objectives

- Explain the way the attachment system works and its evolutionary significance.

- Identify three commonly studied attachment patterns and what is known about the development of those patterns.

- Describe what is known about the consequences of secure versus insecure attachment in adult relationships.

Introduction

Some of the most rewarding experiences in people’s lives involve the development and maintenance of close relationships. For example, some of the greatest sources of joy involve falling in love, starting a family, being reunited with distant loved ones, and sharing experiences with close others. And, not surprisingly, some of the most painful experiences in people’s lives involve the disruption of important social bonds, such as separation from a spouse, losing a parent, or being abandoned by a loved one.

Why do close relationships play such a profound role in human experience? Attachment theory is one approach to understanding the nature of close relationships. In this module, we review the origins of the theory, the core theoretical principles, and some ways in which attachment influences human behavior, thoughts, and feelings across the life course.

Attachment Theory: A Brief History and Core Concepts

Attachment theory was originally developed in the 1940s by John Bowlby, a British psychoanalyst who was attempting to understand the intense distress experienced by infants who had been separated from their parents. Bowlby (1969) observed that infants would go to extraordinary lengths to prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish proximity to a missing parent. For example, he noted that children who had been separated from their parents would often cry, call for their parents, refuse to eat or play, and stand at the door in desperate anticipation of their parents’ return. At the time of Bowlby’s initial writings, psychoanalytic writers held that these expressions were manifestations of immature defense mechanisms that were operating to repress emotional pain. However, Bowlby observed that such expressions are common to a wide variety of mammalian species and speculated that these responses to separation may serve an evolutionary function (see Focus Topic 1).

When Bowlby was originally developing his theory of attachment, there were alternative theoretical perspectives on why infants were emotionally attached to their primary caregivers (most often, their biological mothers). Bowlby and other theorists, for example, believed that there was something important about the responsiveness and contact provided by mothers. Other theorists, in contrast, argued that young infants feel emotionally connected to their mothers because mothers satisfy more basic needs, such as the need for food. That is, the child comes to feel emotionally connected to the mother because she is associated with the reduction of primary drives, such as hunger, rather than the reduction of drives that might be relational in nature.

In a classic set of studies, psychologist Harry Harlow placed young monkeys in cages that contained two artificial, surrogate “mothers” (Harlow, 1958). One of those surrogates was a simple wire contraption; the other was a wire contraption covered in cloth. Both of the surrogate mothers were equipped with a feeding tube so that Harrow and his colleagues had the option to allow the surrogate to deliver or not deliver milk. Harlow found that the young macaques spent a disproportionate amount of time with the cloth surrogate as opposed to the wire surrogate. Moreover, this was true even when the infants were fed by the wire surrogate rather than the cloth surrogate. This suggests that the strong emotional bond that infants form with their primary caregivers is rooted in something more than whether the caregiver provides food per se. Harlow’s research is now regarded as one of the first experimental demonstrations of the importance of “contact comfort” in the establishment of infant–caregiver bonds.

Drawing on evolutionary theory, Bowlby (1969) argued that these behaviors are adaptive responses to separation from a primary attachment figure—a caregiver who provides support, protection, and care. Because human infants, like other mammalian infants, cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of “older and wiser” adults for survival. Bowlby argued that, over the course of evolutionary history, infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure would be more likely to survive to a reproductive age.

According to Bowlby, a motivational system, what he called the attachment behavioral system, was gradually “designed” by natural selection to regulate proximity to an attachment figure. The attachment system functions much like a thermostat that continuously monitors the ambient temperature of a room, comparing that temperature against a desired state and adjusting behavior (e.g., activating the furnace) accordingly. In the case of the attachment system, Bowlby argued that the system continuously monitors the accessibility of the primary attachment figure. If the child perceives the attachment figure to be nearby, accessible, and attentive, then the child feels loved, secure, and confident and, behaviorally, is likely to explore his or her environment, play with others, and be sociable. If, however, the child perceives the attachment figure to be inaccessible, the child experiences anxiety and, behaviorally, is likely to exhibit attachment behaviors ranging from simple visual searching on the low extreme to active searching, following, and vocal signaling on the other. These attachment behaviors continue either until the child is able to reestablish a desirable level of physical or psychological proximity to the attachment figure or until the child exhausts himself or herself or gives up, as may happen in the context of a prolonged separation or loss.

Individual Differences in Infant Attachment

Although Bowlby believed that these basic dynamics captured the way the attachment system works in most children, he recognized that there are individual differences in the way children appraise the accessibility of the attachment figure and how they regulate their attachment behavior in response to threats. However, it was not until his colleague, Mary Ainsworth, began to systematically study infant–parent separations that a formal understanding of these individual differences emerged. Ainsworth and her students developed a technique called the strange situation—a laboratory task for studying infant–parent attachment (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). In the strange situation, 12-month-old infants and their parents are brought to the laboratory and, over a period of approximately 20 minutes, are systematically separated from and reunited with one another. In the strange situation, most children (about 60%) behave in the way implied by Bowlby’s normative theory. Specifically, they become upset when the parent leaves the room, but, when he or she returns, they actively seek the parent and are easily comforted by him or her. Children who exhibit this pattern of behavior are often called secure. Other children (about 20% or less) are ill at ease initially and, upon separation, become extremely distressed. Importantly, when reunited with their parents, these children have a difficult time being soothed and often exhibit conflicting behaviors that suggest they want to be comforted, but that they also want to “punish” the parent for leaving. These children are often called anxious-resistant. The third pattern of attachment that Ainsworth and her colleagues documented is often labeled avoidant. Avoidant children (about 20%) do not consistently behave as if they are stressed by the separation but, upon reunion, actively avoid seeking contact with their parent, sometimes turning their attention to play objects on the laboratory floor.

Ainsworth’s work was important for at least three reasons. First, she provided one of the first empirical demonstrations of how attachment behavior is organized in unfamiliar contexts. Second, she provided the first empirical taxonomy of individual differences in infant attachment patterns. According to her research, at least three types of children exist: those who are secure in their relationship with their parents, those who are anxious-resistant, and those who are anxious-avoidant. Finally, she demonstrated that these individual differences were correlated with infant–parent interactions in the home during the first year of life. Children who appear secure in the strange situation, for example, tend to have parents who are responsive to their needs. Children who appear insecure in the strange situation (i.e., anxious-resistant or avoidant) often have parents who are insensitive to their needs, or inconsistent or rejecting in the care they provide.

Antecedents of Attachment Patterns

In the years that have followed Ainsworth’s ground-breaking research, researchers have investigated a variety of factors that may help determine whether children develop secure or insecure relationships with their primary attachment figures. As mentioned above, one of the key determinants of attachment patterns is the history of sensitive and responsive interactions between the caregiver and the child. In short, when the child is uncertain or stressed, the ability of the caregiver to provide support to the child is critical for his or her psychological development. It is assumed that such supportive interactions help the child learn to regulate his or her emotions, give the child the confidence to explore the environment, and provide the child with a safe haven during stressful circumstances.

Evidence for the role of sensitive caregiving in shaping attachment patterns comes from longitudinal and experimental studies. For example, Grossmann, Grossmann, Spangler, Suess, and Unzner (1985) studied parent–child interactions in the homes of 54 families, up to three times during the first year of the child’s life. At 12 months of age, infants and their mothers participated in the strange situation. Grossmann and her colleagues found that children who were classified as secure in the strange situation at 12 months of age were more likely than children classified as insecure to have mothers who provided responsive care to their children in the home environment.

Van den Boom (1994) developed an intervention that was designed to enhance maternal sensitive responsiveness. When the infants were 9 months of age, the mothers in the intervention group were rated as more responsive and attentive in their interaction with their infants compared to mothers in the control group. In addition, their infants were rated as more sociable, self-soothing, and more likely to explore the environment. At 12 months of age, children in the intervention group were more likely to be classified as secure than insecure in the strange situation.

Attachment Patterns and Child Outcomes

Attachment researchers have studied the association between children’s attachment patterns and their adaptation over time. Researchers have learned, for example, that children who are classified as secure in the strange situation are more likely to have high functioning relationships with peers, to be evaluated favorably by teachers, and to persist with more diligence in challenging tasks. In contrast, insecure-avoidant children are more likely to be construed as “bullies” or to have a difficult time building and maintaining friendships (Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2008).

Attachment in Adulthood

Although Bowlby was primarily focused on understanding the nature of the infant–caregiver relationship, he believed that attachment characterized human experience across the life course. It was not until the mid-1980s, however, that researchers began to take seriously the possibility that attachment processes may be relevant to adulthood. Hazan and Shaver (1987) were two of the first researchers to explore Bowlby’s ideas in the context of romantic relationships. According to Hazan and Shaver, the emotional bond that develops between adult romantic partners is partly a function of the same motivational system—the attachment behavioral system—that gives rise to the emotional bond between infants and their caregivers. Hazan and Shaver noted that in both kinds of relationship, people (a) feel safe and secure when the other person is present; (b) turn to the other person during times of sickness, distress, or fear; (c) use the other person as a “secure base” from which to explore the world; and (d) speak to one another in a unique language, often called “motherese” or “baby talk.” (See Focus Topic 2)

Social media websites and mobile communication services are coming to play an increasing role in people’s lives. Many people use Facebook, for example, to keep in touch with family and friends, to update their loved ones regarding things going on in their lives, and to meet people who share similar interests. Moreover, modern cellular technology allows people to get in touch with their loved ones much easier than was possible a mere 20 years ago.

From an attachment perspective, these innovations in communications technology are important because they allow people to stay connected virtually to their attachment figures—regardless of the physical distance that might exist between them. Recent research has begun to examine how attachment processes play out in the use of social media. Oldmeadow, Quinn, and Kowert (2013), for example, studied a diverse sample of individuals and assessed their attachment security and their use of Facebook. Oldmeadow and colleagues found that the use of Facebook may serve attachment functions. For example, people were more likely to report using Facebook to connect with others when they were experiencing negative emotions. In addition, the researchers found that people who were more anxious in their attachment orientation were more likely to use Facebook frequently, but people who were more avoidant used Facebook less and were less open on the site.

On the basis of these parallels, Hazan and Shaver (1987) argued that adult romantic relationships, such as infant–caregiver relationships, are attachments. According to Hazan and Shaver, individuals gradually transfer attachment-related functions from parents to peers as they develop. Thus, although young children tend to use their parents as their primary attachment figures, as they reach adolescence and young adulthood, they come to rely more upon close friends and/or romantic partners for basic attachment-related functions. Thus, although a young child may turn to his or her mother for comfort, support, and guidance when distressed, scared, or ill, young adults may be more likely to turn to their romantic partners for these purposes under similar situations.

Hazan and Shaver (1987) asked a diverse sample of adults to read the three paragraphs below and indicate which paragraph best characterized the way they think, feel, and behave in close relationships:

- I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.

- I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.

- I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.

Conceptually, these descriptions were designed to represent what Hazan and Shaver considered to be adult analogues of the kinds of attachment patterns Ainsworth described in the strange situation (avoidant, secure, and anxious, respectively). Hazan and Shaver (1987) found that the distribution of the three patterns was similar to that observed in infancy. In other words, about 60% of adults classified themselves as secure (paragraph B), about 20% described themselves as avoidant (paragraph A), and about 20% described themselves as anxious-resistant (paragraph C). Moreover, they found that people who described themselves as secure, for example, were more likely to report having had warm and trusting relationships with their parents when they were growing up. In addition, they were more likely to have positive views of romantic relationships. Based on these findings, Hazan and Shaver (1987) concluded that the same kinds of individual differences that exist in infant attachment also exist in adulthood.

Research on Attachment in Adulthood

Attachment theory has inspired a large amount of literature in social, personality, and clinical psychology. In the sections below, I provide a brief overview of some of the major research questions and what researchers have learned about attachment in adulthood.

Who Ends Up with Whom?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding—the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). But we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners—and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996), for example, studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure, Lydon, Baccus, & Baldwin, 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Relationship Functioning

Research has consistently demonstrated that individuals who are relatively secure are more likely than insecure individuals to have high functioning relationships—relationships that are more satisfying, more enduring, and less characterized by conflict. For example, Feeney and Noller (1992) found that insecure individuals were more likely than secure individuals to experience a breakup of their relationship. In addition, secure individuals are more likely to report satisfying relationships (e.g., Collins & Read, 1990) and are more likely to provide support to their partners when their partners were feeling distressed (Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992).

Do Early Experiences Shape Adult Attachment?

The majority of research on this issue is retrospective—that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades 1 to 3, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear: Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. But that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences—including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Outside Resources

- Web: Center for the Developing Child, Harvard University

- http://developingchild.harvard.edu

- Web: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning

- http://casel.org

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. Retrieved from:

- http://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~schaller/Psyc591Readings/HazanShaver1987.pdf

- Hofer, M. A. (2006). Psychobiological roots of early attachment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 84-88. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00412.x

- http://cdp.sagepub.com/content/15/2/84.short

- Survey: Learn more about your attachment patterns via this online survey

- http://www.yourpersonality.net/relstructures/

Discussion Questions

- If parent–child relationships naturally change as the child matures, would you expect that the security of attachment might also change over time? What reasons would account for your expectation?

- In what ways does a child’s developing theory of mind resemble how scientists create, refine, and use theories in their work? In other words, would it be appropriate to think of children as informal scientists in their development of social understanding?

- If there is a poor goodness of fit between a child’s temperament and characteristics of parental care, what can be done to create a better match? Provide a specific example of how this might occur.

- What are the contributions that parents offer to the development of social and emotional competence in children? Answer this question again with respect to peer contributions.

- What kind of relationship did you have with your parents or primary caregivers when you were young? Do you think that had any bearing on the way you related to others (e.g., friends, relationship partners) as you grew older?

- There is variation across cultures in the extent to which people value independence. Do you think this might have implications for the development of attachment patterns?

- As parents age, it is not uncommon for them to have to depend on their adult children. Do you think that people’s history of experiences in their relationships with their parents might shape people’s willingness to provide care for their aging parents? In other words, are secure adults more likely to provide responsive care to their aging parents?

- Some people, despite reporting insecure relationships with their parents, report secure, well-functioning relationships with their spouses. What kinds of experiences do you think might enable someone to develop a secure relationship with their partners despite having an insecure relationship with other central figures in their lives?

- Most attachment research on adults focuses on attachment to peers (e.g., romantic partners). What other kinds of things may serve as attachment figures? Do you think siblings, pets, or gods can serve as attachment figures?

Vocabulary

- A parenting style characterized by high (but reasonable) expectations for children’s behavior, good communication, warmth and nurturance, and the use of reasoning (rather than coercion) as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior.

- Conscience

- The cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internal standards of conduct.

- Effortful control

- A temperament quality that enables children to be more successful in motivated self-regulation.

- Family Stress Model

- A description of the negative effects of family financial difficulty on child adjustment through the effects of economic stress on parents’ depressed mood, increased marital problems, and poor parenting.

- Gender schemas

- Organized beliefs and expectations about maleness and femaleness that guide children’s thinking about gender.

- Goodness of fit

- The match or synchrony between a child’s temperament and characteristics of parental care that contributes to positive or negative personality development. A good “fit” means that parents have accommodated to the child’s temperamental attributes, and this contributes to positive personality growth and better adjustment.

- Security of attachment

- An infant’s confidence in the sensitivity and responsiveness of a caregiver, especially when he or she is needed. Infants can be securely attached or insecurely attached.

- The process by which one individual consults another’s emotional expressions to determine how to evaluate and respond to circumstances that are ambiguous or uncertain.

- Temperament

- Early emerging differences in reactivity and self-regulation, which constitutes a foundation for personality development.

- Theory of mind

- Children’s growing understanding of the mental states that affect people’s behavior.

- Attachment behavioral system

- A motivational system selected over the course of evolution to maintain proximity between a young child and his or her primary attachment figure.

- Attachment behaviors

- Behaviors and signals that attract the attention of a primary attachment figure and function to prevent separation from that individual or to reestablish proximity to that individual (e.g., crying, clinging).

- Attachment figure

- Someone who functions as the primary safe haven and secure base for an individual. In childhood, an individual’s attachment figure is often a parent. In adulthood, an individual’s attachment figure is often a romantic partner.

- Attachment patterns

- (also called “attachment styles” or “attachment orientations”) Individual differences in how securely (vs. insecurely) people think, feel, and behave in attachment relationships.

- Strange situation

- A laboratory task that involves briefly separating and reuniting infants and their primary caregivers as a way of studying individual differences in attachment behavior.

References

- Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. Sheffield, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11–34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Belsky, J., & Pasco Fearon, R. M. (2008). Precursors of attachment security. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 295–316). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Bukowski, W. M., Buhrmester, D., & Underwood, M. K. (2011). Peer relations as a developmental context. In M. K. Underwood & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social development(pp. 153–179). New York, NY: Guilford

- Cassidy, J. (2008). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 3–22). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1999). Goodness of fit: Clinical applications from infancy through adult life. New York, NY: Brunner-Mazel/Taylor & Francis.

- Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704

- Emery, R. E. (1999). Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Feinman, S. (Ed.) (1992). Social referencing and the social construction of reality in infancy. New York, NY: Plenum.

- Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A. N., & Kuhl, P. K. (2001). The scientist in the crib. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

- Kochanska, G. (2002). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 191–195.

- Kochanska, G., Kim, S., Barry, R. A., & Philibert, R. A. (2011). Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology, 23, 605-616.

- Leslie, A. M. (1994). ToMM, ToBy, and agency: Core architecture and domain specificity in cognition and culture. In L. Hirschfeld & S. Gelman (Eds.), Mapping the mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture(pp. 119-148). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Meltzoff, A. N. (1995). Understanding the intentions of others: Re-enactment of intended acts by 18-month-old children. Developmental Psychology, 31, 838-850.

- Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R., Chen, X., Bowker, J., & McDonald, K. L. (2011). Peer relationships in childhood. In M. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (6th ed. pp. 519–570). New York, NY: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

- Ruble, D. N., Martin, C., & Berenbaum, S. (2006). Gender development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 858–932). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Solomon, J., & George, C. (2008). The measurement of attachment security and related constructs in infancy and early childhood. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 383–416). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Thompson, R. A. (2012). Whither the preconventional child? Toward a life-span moral development theory. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 423–429.

- Thompson, R. A. (2008). Early attachment and later development: Familiar questions, new answers. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 348–365). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Thompson, R. A. (2006a). Conversation and developing understanding: Introduction to the special issue. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 1–16.

- Thompson, R. A. (2006b). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, self, conscience. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 24–98). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Thompson, R. A., Winer, A. C., & Goodvin, R. (2010). The individual child: Temperament, emotion, self, and personality. In M. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (6th ed., pp. 423–464). New York, NY: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

- Wellman, H. M. (2011). Developing a theory of mind. In U. Goswami (Ed.), Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development (2nd ed., pp. 258–284). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books

- Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342.

- Collins, N., & Read, S. (1990). Adult attachment, working models and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644-663.

- Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1992). Attachment style and romantic love: Relationship dissolution. Australian Journal of Psychology, 44, 69–74.

- Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 8817-838.

- Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136.

- Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Spangler, G., Suess, G., & Unzner, L. (1985). Maternal sensitivity and newborns orientation responses as related to quality of attachment in northern Germany. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2), 233–256.

- Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673–685.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

- Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2012). Attachment coregulation: A longitudinal investigation of the coordination in romantic partners’ attachment styles. Manuscript under review.

- McClure, M. J., Lydon., J. E., Baccus, J., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of the anxiously attached at speed-dating: Being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1024–1036.

- Oldmeadow, J. A., Quinn, S., & Kowert, R. (2013). Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 1142–1149.

- Simpson, J. A., Collins, W. A., Tran, S., & Haydon, K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 355–367.

- Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., & Nelligan, J. S. (1992). Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 434–446.

- Weinfield, N. S., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. A. (2008). Individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment: Conceptual and empirical aspects of security. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 78–101). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 65, 1457–1477.

Authors

Ross Thompson

Ross ThompsonRoss A. Thompson is Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Davis. His research focuses on early social, emotional, and personality development, and the applications of this research to public policy concerning children and families. He has been recognized for his research contributions, teaching achievements, and public service.

R. Chris Fraley

R. Chris FraleyR. Chris Fraley is a professor at the University of Illinois’s Department of Psychology. In 2007 he received the American Psychological Association’s Distinguished Scientific Award for Early Career Contribution to Psychology in the area of Individual Differences. He conducts research on attachment, close relationships, and personality development.

Creative Commons License

Attachment Through the Life Course by R. Chris Fraley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Attachment Through the Life Course by R. Chris Fraley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Creative Commons License

Social and Personality Development in Childhood by Ross Thompson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Social and Personality Development in Childhood by Ross Thompson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.