This module consists of two parts: psychology as science and the history of psychology. Together they serve as an Introduction to Psychology, or in other words, your “Chapter One.” This material is most commonly presented at the beginning of PSY1101 courses.

Contents

- 1 Why Science?

- 2 Scientific Advances and World Progress

- 3 What Is Science?

- 4 Psychology as a Science

- 5 Psychological Science is Useful

- 6 Ethics of Scientific Psychology

- 7 Why Learn About Scientific Psychology?

- 8 History of Psychology

- 9 History Appreciaton

- 10 A Prehistory of Psychology

- 11 Physiology and Psychophysics

- 12 Scientific Psychology Comes to the United States

- 13 Toward a Functional Psychology

- 14 The Growth of Psychology

- 15 Applied Psychology in America

- 16 Psychology as a Profession

- 17 Psychology and Society

- 18 Conclusions

- 19 Timeline

Why Science?

University of Utah, University of Virginia

Scientific research has been one of the great drivers of progress in human history, and the dramatic changes we have seen during the past century are due primarily to scientific findings—modern medicine, electronics, automobiles and jets, birth control, and a host of other helpful inventions. Psychologists believe that scientific methods can be used in the behavioral domain to understand and improve the world. Although psychology trails the biological and physical sciences in terms of progress, we are optimistic based on discoveries to date that scientific psychology will make many important discoveries that can benefit humanity. This module outlines the characteristics of the science, and the promises it holds for understanding behavior. The ethics that guide psychological research are briefly described. It concludes with the reasons you should learn about scientific psychology

- Describe how scientific research has changed the world.

- Describe the key characteristics of the scientific approach.

- Discuss a few of the benefits, as well as problems that have been created by science.

- Describe several ways that psychological science has improved the world.

- Describe a number of the ethical guidelines that psychologists follow.

Scientific Advances and World Progress

There are many people who have made positive contributions to humanity in modern times. Take a careful look at the names on the following list. Which of these individuals do you think has helped humanity the most?

- Mother Teresa

- Albert Schweitzer

- Edward Jenner

- Norman Borlaug

- Fritz Haber

The usual response to this question is “Who on earth are Jenner, Borlaug, and Haber?” Many people know that Mother Teresa helped thousands of people living in the slums of Kolkata (Calcutta). Others recall that Albert Schweitzer opened his famous hospital in Africa and went on to earn the Nobel Peace Prize. The other three historical figures, on the other hand, are far less well known. Jenner, Borlaug, and Haber were scientists whose research discoveries saved millions, and even billions, of lives. Dr. Edward Jenner is often considered the “father of immunology” because he was among the first to conceive of and test vaccinations. His pioneering work led directly to the eradication of smallpox. Many other diseases have been greatly reduced because of vaccines discovered using science—measles, pertussis, diphtheria, tetanus, typhoid, cholera, polio, hepatitis—and all are the legacy of Jenner. Fritz Haber and Norman Borlaug saved more than a billion human lives. They created the “Green Revolution” by producing hybrid agricultural crops and synthetic fertilizer. Humanity can now produce food for the seven billion people on the planet, and the starvation that does occur is related to political and economic factors rather than our collective ability to produce food.

If you examine major social and technological changes over the past century most of them can be directly attributed to science. The world in 1914 was very different than the one we see today (Easterbrook, 2003). There were few cars and most people traveled by foot, horseback, or carriage. There were no radios, televisions, birth control pills, artificial hearts or antibiotics. Only a small portion of the world had telephones, refrigeration or electricity. These days we find that 80% of all households have television and 84% have electricity. It is estimated that three quarters of the world’s population has access to a mobile phone! Life expectancy was 47 years in 1900 and 79 years in 2010. The percentage of hungry and malnourished people in the world has dropped substantially across the globe. Even average levels of I.Q. have risen dramatically over the past century due to better nutrition and schooling.

All of these medical advances and technological innovations are the direct result of scientific research and understanding. In the modern age it is easy to grow complacent about the advances of science but make no mistake about it—science has made fantastic discoveries, and continues to do so. These discoveries have completely changed our world.

What Is Science?

What is this process we call “science,” which has so dramatically changed the world? Ancient people were more likely to believe in magical and supernatural explanations for natural phenomena such as solar eclipses or thunderstorms. By contrast, scientifically minded people try to figure out the natural world through testing and observation. Specifically, science is the use of systematic observation in order to acquire knowledge. For example, children in a science class might combine vinegar and baking soda to observe the bubbly chemical reaction. These empirical methods are wonderful ways to learn about the physical and biological world. Science is not magic—it will not solve all human problems, and might not answer all our questions about behavior. Nevertheless, it appears to be the most powerful method we have for acquiring knowledge about the observable world. The essential elements of science are as follows:

- Systematic observation is the core of science. Scientists observe the world, in a very organized way. We often measure the phenomenon we are observing. We record our observations so that memory biases are less likely to enter in to our conclusions. We are systematic in that we try to observe under controlled conditions, and also systematically vary the conditions of our observations so that we can see variations in the phenomena and understand when they occur and do not occur.

Systematic observation is the core of science. [Image: Cvl Neuro, https://goo.gl/Avbju7, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://goo.gl/uhHola] - Observation leads to hypotheses we can test. When we develop hypotheses and theories, we state them in a way that can be tested. For example, you might make the claim that candles made of paraffin wax burn more slowly than do candles of the exact same size and shape made from bee’s wax. This claim can be readily tested by timing the burning speed of candles made from these materials.

- Science is democratic. People in ancient times may have been willing to accept the views of their kings or pharaohs as absolute truth. These days, however, people are more likely to want to be able to form their own opinions and debate conclusions. Scientists are skeptical and have open discussions about their observations and theories. These debates often occur as scientists publish competing findings with the idea that the best data will win the argument.

- Science is cumulative. We can learn the important truths discovered by earlier scientists and build on them. Any physics student today knows more about physics than Sir Isaac Newton did even though Newton was possibly the most brilliant physicist of all time. A crucial aspect of scientific progress is that after we learn of earlier advances, we can build upon them and move farther along the path of knowledge.

Psychology as a Science

Even in modern times many people are skeptical that psychology is really a science. To some degree this doubt stems from the fact that many psychological phenomena such as depression, intelligence, and prejudice do not seem to be directly observable in the same way that we can observe the changes in ocean tides or the speed of light. Because thoughts and feelings are invisible many early psychological researchers chose to focus on behavior. You might have noticed that some people act in a friendly and outgoing way while others appear to be shy and withdrawn. If you have made these types of observations then you are acting just like early psychologists who used behavior to draw inferences about various types of personality. By using behavioral measures and rating scales it is possible to measure thoughts and feelings. This is similar to how other researchers explore “invisible” phenomena such as the way that educators measure academic performance or economists measure quality of life.

One important pioneering researcher was Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin who lived in England during the late 1800s. Galton used patches of color to test people’s ability to distinguish between them. He also invented the self-report questionnaire, in which people offered their own expressed judgments or opinions on various matters. Galton was able to use self-reports to examine—among other things—people’s differing ability to accurately judge distances.

Although he lacked a modern understanding of genetics Galton also had the idea that scientists could look at the behaviors of identical and fraternal twins to estimate the degree to which genetic and social factors contribute to personality; a puzzling issue we currently refer to as the “nature-nurture question.”

In modern times psychology has become more sophisticated. Researchers now use better measures, more sophisticated study designs and better statistical analyses to explore human nature. Simply take the example of studying the emotion of happiness. How would you go about studying happiness? One straightforward method is to simply ask people about their happiness and to have them use a numbered scale to indicate their feelings. There are, of course, several problems with this. People might lie about their happiness, might not be able to accurately report on their own happiness, or might not use the numerical scale in the same way. With these limitations in mind modern psychologists employ a wide range of methods to assess happiness. They use, for instance, “peer report measures” in which they ask close friends and family members about the happiness of a target individual. Researchers can then compare these ratings to the self-report ratings and check for discrepancies. Researchers also use memory measures, with the idea that dispositionally positive people have an easier time recalling pleasant events and negative people have an easier time recalling unpleasant events. Modern psychologists even use biological measures such as saliva cortisol samples (cortisol is a stress related hormone) or fMRI images of brain activation (the left pre-frontal cortex is one area of brain activity associated with good moods).

Despite our various methodological advances it is true that psychology is still a very young science. While physics and chemistry are hundreds of years old psychology is barely a hundred and fifty years old and most of our major findings have occurred only in the last 60 years. There are legitimate limits to psychological science but it is a science nonetheless.

Psychological Science is Useful

Psychological science is useful for creating interventions that help people live better lives. A growing body of research is concerned with determining which therapies are the most and least effective for the treatment of psychological disorders.

For example, many studies have shown that cognitive behavioral therapy can help many people suffering from depression and anxiety disorders (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hoffman & Smits, 2008). In contrast, research reveals that some types of therapies actually might be harmful on average (Lilienfeld, 2007).

In organizational psychology, a number of psychological interventions have been found by researchers to produce greater productivity and satisfaction in the workplace (e.g., Guzzo, Jette, & Katzell, 1985). Human factor engineers have greatly increased the safety and utility of the products we use. For example, the human factors psychologist Alphonse Chapanis and other researchers redesigned the cockpit controls of aircraft to make them less confusing and easier to respond to, and this led to a decrease in pilot errors and crashes.

Forensic sciences have made courtroom decisions more valid. We all know of the famous cases of imprisoned persons who have been exonerated because of DNA evidence. Equally dramatic cases hinge on psychological findings. For instance, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has conducted research demonstrating the limits and unreliability of eyewitness testimony and memory. Thus, psychological findings are having practical importance in the world outside the laboratory. Psychological science has experienced enough success to demonstrate that it works, but there remains a huge amount yet to be learned.

Ethics of Scientific Psychology

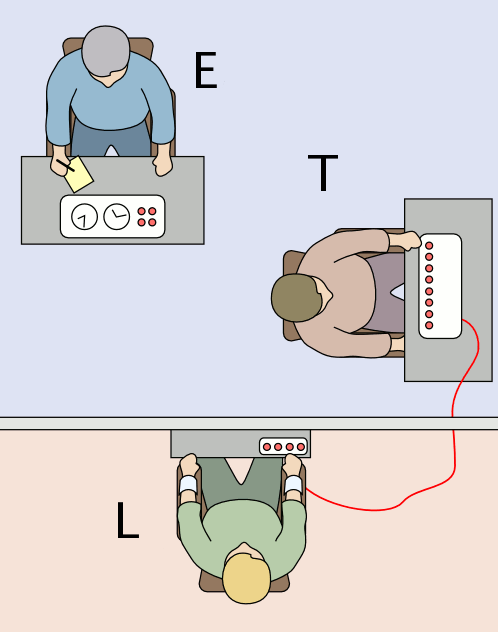

Psychology differs somewhat from the natural sciences such as chemistry in that researchers conduct studies with human research participants. Because of this there is a natural tendency to want to guard research participants against potential psychological harm. For example, it might be interesting to see how people handle ridicule but it might not be advisable to ridicule research participants.

Scientific psychologists follow a specific set of guidelines for research known as a code of ethics. There are extensive ethical guidelines for how human participants should be treated in psychological research (Diener & Crandall, 1978; Sales & Folkman, 2000). Following are a few highlights:

- Informed consent. In general, people should know when they are involved in research, and understand what will happen to them during the study. They should then be given a free choice as to whether to participate.

- Confidentiality. Information that researchers learn about individual participants should not be made public without the consent of the individual.

- Privacy. Researchers should not make observations of people in private places such as their bedrooms without their knowledge and consent. Researchers should not seek confidential information from others, such as school authorities, without consent of the participant or his or her guardian.

- Benefits. Researchers should consider the benefits of their proposed research and weigh these against potential risks to the participants. People who participate in psychological studies should be exposed to risk only if they fully understand these risks and only if the likely benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

- Deception. Some researchers need to deceive participants in order to hide the true nature of the study. This is typically done to prevent participants from modifying their behavior in unnatural ways. Researchers are required to “debrief” their participants after they have completed the study. Debriefing is an opportunity to educate participants about the true nature of the study.

Why Learn About Scientific Psychology?

I once had a psychology professor who asked my class why we were taking a psychology course. Our responses give the range of reasons that people want to learn about psychology:

- To understand ourselves

- To understand other people and groups

- To be better able to influence others, for example, in socializing children or motivating employees

- To learn how to better help others and improve the world, for example, by doing effective psychotherapy

- To learn a skill that will lead to a profession such as being a social worker or a professor

- To learn how to evaluate the research claims you hear or read about

- Because it is interesting, challenging, and fun! People want to learn about psychology because this is exciting in itself, regardless of other positive outcomes it might have. Why do we see movies? Because they are fun and exciting, and we need no other reason. Thus, one good reason to study psychology is that it can be rewarding in itself.

History of Psychology

By David B. Baker and Heather Sperry

University of Akron, The University of Akron

This module provides an introduction and overview of the historical development of the science and practice of psychology in America. Ever-increasing specialization within the field often makes it difficult to discern the common roots from which the field of psychology has evolved. By exploring this shared past, students will be better able to understand how psychology has developed into the discipline we know today.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the precursors to the establishment of the science of psychology.

- Identify key individuals and events in the history of American psychology.

- Describe the rise of professional psychology in America.

- Develop a basic understanding of the processes of scientific development and change.

- Recognize the role of women and people of color in the history of American psychology.

History Appreciaton

It is always a difficult question to ask, where to begin to tell the story of the history of psychology. Some would start with ancient Greece; others would look to a demarcation in the late 19th century when the science of psychology was formally proposed and instituted. These two perspectives, and all that is in between, are appropriate for describing a history of psychology. The interested student will have no trouble finding an abundance of resources on all of these time frames and perspectives (Goodwin, 2011; Leahey, 2012; Schultz & Schultz, 2007). For the purposes of this module, we will examine the development of psychology in America and use the mid-19th century as our starting point. For the sake of convenience, we refer to this as a history of modern psychology.

Psychology is an exciting field and the history of psychology offers the opportunity to make sense of how it has grown and developed. The history of psychology also provides perspective. Rather than a dry collection of names and dates, the history of psychology tells us about the important intersection of time and place that defines who we are. Consider what happens when you meet someone for the first time. The conversation usually begins with a series of questions such as, “Where did you grow up?” “How long have you lived here?” “Where did you go to school?” The importance of history in defining who we are cannot be understated. Whether you are seeing a physician, talking with a counselor, or applying for a job, everything begins with a history. The same is true for studying the history of psychology; getting a history of the field helps to make sense of where we are and how we got here.

A Prehistory of Psychology

Precursors to American psychology can be found in philosophy and physiology. Philosophers such as John Locke (1632–1704) and Thomas Reid (1710–1796) promoted empiricism, the idea that all knowledge comes from experience. The work of Locke, Reid, and others emphasized the role of the human observer and the primacy of the senses in defining how the mind comes to acquire knowledge. In American colleges and universities in the early 1800s, these principles were taught as courses on mental and moral philosophy. Most often these courses taught about the mind based on the faculties of intellect, will, and the senses (Fuchs, 2000).

Physiology and Psychophysics

Philosophical questions about the nature of mind and knowledge were matched in the 19th century by physiological investigations of the sensory systems of the human observer. German physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) measured the speed of the neural impulse and explored the physiology of hearing and vision. His work indicated that our senses can deceive us and are not a mirror of the external world. Such work showed that even though the human senses were fallible, the mind could be measured using the methods of science. In all, it suggested that a science of psychology was feasible.

An important implication of Helmholtz’s work was that there is a psychological reality and a physical reality and that the two are not identical. This was not a new idea; philosophers like John Locke had written extensively on the topic, and in the 19th century, philosophical speculation about the nature of mind became subject to the rigors of science.

The question of the relationship between the mental (experiences of the senses) and the material (external reality) was investigated by a number of German researchers including Ernst Weber and Gustav Fechner. Their work was called psychophysics, and it introduced methods for measuring the relationship between physical stimuli and human perception that would serve as the basis for the new science of psychology (Fancher & Rutherford, 2011).

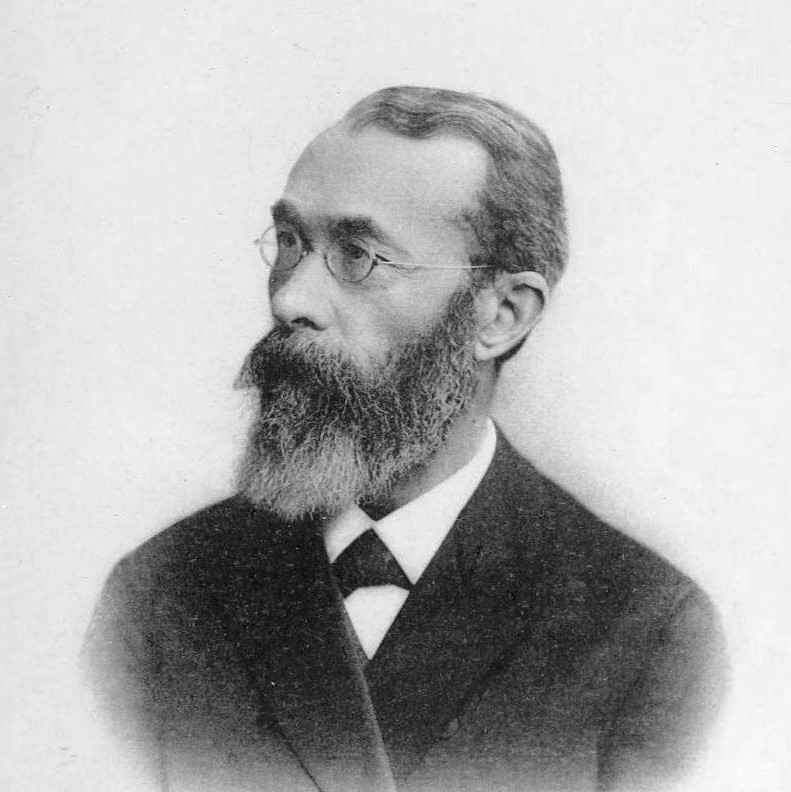

The formal development of modern psychology is usually credited to the work of German physician, physiologist, and philosopher Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920). Wundt helped to establish the field of experimental psychology by serving as a strong promoter of the idea that psychology could be an experimental field and by providing classes, textbooks, and a laboratory for training students. In 1875, he joined the faculty at the University of Leipzig and quickly began to make plans for the creation of a program of experimental psychology. In 1879, he complemented his lectures on experimental psychology with a laboratory experience: an event that has served as the popular date for the establishment of the science of psychology.

The response to the new science was immediate and global. Wundt attracted students from around the world to study the new experimental psychology and work in his lab. Students were trained to offer detailed self-reports of their reactions to various stimuli, a procedure known as introspection. The goal was to identify the elements of consciousness. In addition to the study of sensation and perception, research was done on mental chronometry, more commonly known as reaction time. The work of Wundt and his students demonstrated that the mind could be measured and the nature of consciousness could be revealed through scientific means. It was an exciting proposition, and one that found great interest in America. After the opening of Wundt’s lab in 1879, it took just four years for the first psychology laboratory to open in the United States (Benjamin, 2007).

Scientific Psychology Comes to the United States

Wundt’s version of psychology arrived in America most visibly through the work of Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927). A student of Wundt’s, Titchener brought to America a brand of experimental psychology referred to as “structuralism.” Structuralists were interested in the contents of the mind—what the mind is. For Titchener, the general adult mind was the proper focus for the new psychology, and he excluded from study those with mental deficiencies, children, and animals (Evans, 1972; Titchener, 1909).

Experimental psychology spread rather rapidly throughout North America. By 1900, there were more than 40 laboratories in the United States and Canada (Benjamin, 2000). Psychology in America also organized early with the establishment of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1892. Titchener felt that this new organization did not adequately represent the interests of experimental psychology, so, in 1904, he organized a group of colleagues to create what is now known as the Society of Experimental Psychologists (Goodwin, 1985). The group met annually to discuss research in experimental psychology. Reflecting the times, women researchers were not invited (or welcome). It is interesting to note that Titchener’s first doctoral student was a woman, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939). Despite many barriers, in 1894, Washburn became the first woman in America to earn a Ph.D. in psychology and, in 1921, only the second woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987).

Striking a balance between the science and practice of psychology continues to this day. In 1988, the American Psychological Society (now known as the Association for Psychological Science) was founded with the central mission of advancing psychological science.

Toward a Functional Psychology

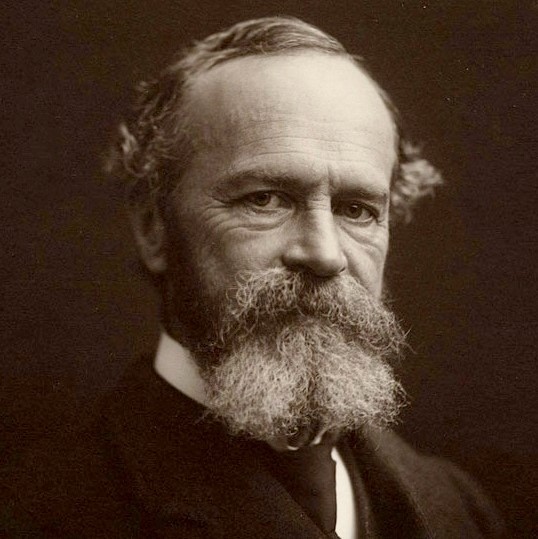

While Titchener and his followers adhered to a structural psychology, others in America were pursuing different approaches. William James, G. Stanley Hall, and James McKeen Cattell were among a group that became identified with “functionalism.” Influenced by Darwin’s evolutionary theory, functionalists were interested in the activities of the mind—what the mind does. An interest in functionalism opened the way for the study of a wide range of approaches, including animal and comparative psychology (Benjamin, 2007).

William James (1842–1910) is regarded as writing perhaps the most influential and important book in the field of psychology, Principles of Psychology,published in 1890. Opposed to the reductionist ideas of Titchener, James proposed that consciousness is ongoing and continuous; it cannot be isolated and reduced to elements. For James, consciousness helped us adapt to our environment in such ways as allowing us to make choices and have personal responsibility over those choices.

At Harvard, James occupied a position of authority and respect in psychology and philosophy. Through his teaching and writing, he influenced psychology for generations. One of his students, Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930), faced many of the challenges that confronted Margaret Floy Washburn and other women interested in pursuing graduate education in psychology. With much persistence, Calkins was able to study with James at Harvard. She eventually completed all the requirements for the doctoral degree, but Harvard refused to grant her a diploma because she was a woman. Despite these challenges, Calkins went on to become an accomplished researcher and the first woman elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1905 (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987).

G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924) made substantial and lasting contributions to the establishment of psychology in the United States. At Johns Hopkins University, he founded the first psychological laboratory in America in 1883. In 1887, he created the first journal of psychology in America, American Journal of Psychology. In 1892, he founded the American Psychological Association (APA); in 1909, he invited and hosted Freud at Clark University (the only time Freud visited America). Influenced by evolutionary theory, Hall was interested in the process of adaptation and human development. Using surveys and questionnaires to study children, Hall wrote extensively on child development and education. While graduate education in psychology was restricted for women in Hall’s time, it was all but non-existent for African Americans. In another first, Hall mentored Francis Cecil Sumner (1895–1954) who, in 1920, became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in psychology in America (Guthrie, 2003).

James McKeen Cattell (1860–1944) received his Ph.D. with Wundt but quickly turned his interests to the assessment of individual differences. Influenced by the work of Darwin’s cousin, Frances Galton, Cattell believed that mental abilities such as intelligence were inherited and could be measured using mental tests. Like Galton, he believed society was better served by identifying those with superior intelligence and supported efforts to encourage them to reproduce. Such beliefs were associated with eugenics (the promotion of selective breeding) and fueled early debates about the contributions of heredity and environment in defining who we are. At Columbia University, Cattell developed a department of psychology that became world famous also promoting psychological science through advocacy and as a publisher of scientific journals and reference works (Fancher, 1987; Sokal, 1980).

The Growth of Psychology

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, psychology continued to grow and flourish in America. It was large enough to accommodate varying points of view on the nature of mind and behavior. Gestalt psychology is a good example. The Gestalt movement began in Germany with the work of Max Wertheimer (1880–1943). Opposed to the reductionist approach of Wundt’s laboratory psychology, Wertheimer and his colleagues Kurt Koffka (1886–1941), Wolfgang Kohler (1887–1967), and Kurt Lewin (1890–1947) believed that studying the whole of any experience was richer than studying individual aspects of that experience. The saying “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is a Gestalt perspective. Consider that a melody is an additional element beyond the collection of notes that comprise it. The Gestalt psychologists proposed that the mind often processes information simultaneously rather than sequentially. For instance, when you look at a photograph, you see a whole image, not just a collection of pixels of color. Using Gestalt principles, Wertheimer and his colleagues also explored the nature of learning and thinking. Most of the German Gestalt psychologists were Jewish and were forced to flee the Nazi regime due to the threats posed on both academic and personal freedoms. In America, they were able to introduce a new audience to the Gestalt perspective, demonstrating how it could be applied to perception and learning (Wertheimer, 1938). In many ways, the work of the Gestalt psychologists served as a precursor to the rise of cognitive psychology in America (Benjamin, 2007).

Behaviorism emerged early in the 20th century and became a major force in American psychology. Championed by psychologists such as John B. Watson (1878–1958) and B. F. Skinner (1904–1990), behaviorism rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior. Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) influenced early behaviorism in America. His work on conditioned learning, popularly referred to as classical conditioning, provided support for the notion that learning and behavior were controlled by events in the environment and could be explained with no reference to mind or consciousness (Fancher, 1987).

For decades, behaviorism dominated American psychology. By the 1960s, psychologists began to recognize that behaviorism was unable to fully explain human behavior because it neglected mental processes. The turn toward a cognitive psychology was not new. In the 1930s, British psychologist Frederic C. Bartlett (1886–1969) explored the idea of the constructive mind, recognizing that people use their past experiences to construct frameworks in which to understand new experiences. Some of the major pioneers in American cognitive psychology include Jerome Bruner (1915–), Roger Brown (1925–1997), and George Miller (1920–2012). In the 1950s, Bruner conducted pioneering studies on cognitive aspects of sensation and perception. Brown conducted original research on language and memory, coined the term “flashbulb memory,” and figured out how to study the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon (Benjamin, 2007). Miller’s research on working memory is legendary. His 1956 paper “The Magic Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information”is one of the most highly cited papers in psychology. A popular interpretation of Miller’s research was that the number of bits of information an average human can hold in working memory is 7 ± 2. Around the same time, the study of computer science was growing and was used as an analogy to explore and understand how the mind works. The work of Miller and others in the 1950s and 1960s has inspired tremendous interest in cognition and neuroscience, both of which dominate much of contemporary American psychology.

Applied Psychology in America

In America, there has always been an interest in the application of psychology to everyday life. Mental testing is an important example. Modern intelligence tests were developed by the French psychologist Alfred Binet (1857–1911). His goal was to develop a test that would identify schoolchildren in need of educational support. His test, which included tasks of reasoning and problem solving, was introduced in the United States by Henry Goddard (1866–1957) and later standardized by Lewis Terman (1877–1956) at Stanford University. The assessment and meaning of intelligence has fueled debates in American psychology and society for nearly 100 years. Much of this is captured in the nature-nurture debate that raises questions about the relative contributions of heredity and environment in determining intelligence (Fancher, 1987).

Applied psychology was not limited to mental testing. What psychologists were learning in their laboratories was applied in many settings including the military, business, industry, and education. The early 20th century was witness to rapid advances in applied psychology. Hugo Munsterberg (1863–1916) of Harvard University made contributions to such areas as employee selection, eyewitness testimony, and psychotherapy. Walter D. Scott (1869–1955) and Harry Hollingworth (1880–1956) produced original work on the psychology of advertising and marketing. Lillian Gilbreth (1878–1972) was a pioneer in industrial psychology and engineering psychology. Working with her husband, Frank, they promoted the use of time and motion studies to improve efficiency in industry. Lillian also brought the efficiency movement to the home, designing kitchens and appliances including the pop-up trashcan and refrigerator door shelving. Their psychology of efficiency also found plenty of applications at home with their 12 children. The experience served as the inspiration for the movie Cheaper by the Dozen (Benjamin, 2007).

Clinical psychology was also an early application of experimental psychology in America. Lightner Witmer (1867–1956) received his Ph.D. in experimental psychology with Wilhelm Wundt and returned to the University of Pennsylvania, where he opened a psychological clinic in 1896. Witmer believed that because psychology dealt with the study of sensation and perception, it should be of value in treating children with learning and behavioral problems. He is credited as the founder of both clinical and school psychology (Benjamin & Baker, 2004).

Psychology as a Profession

As the roles of psychologists and the needs of the public continued to change, it was necessary for psychology to begin to define itself as a profession. Without standards for training and practice, anyone could use the title psychologist and offer services to the public. As early as 1917, applied psychologists organized to create standards for education, training, and licensure. By the 1930s, these efforts led to the creation of the American Association for Applied Psychology (AAAP). While the American Psychological Association (APA) represented the interests of academic psychologists, AAAP served those in education, industry, consulting, and clinical work.

The advent of WWII changed everything. The psychiatric casualties of war were staggering, and there were simply not enough mental health professionals to meet the need. Recognizing the shortage, the federal government urged the AAAP and APA to work together to meet the mental health needs of the nation. The result was the merging of the AAAP and the APA and a focus on the training of professional psychologists. Through the provisions of National Mental Health Act of 1946, funding was made available that allowed the APA, the Veterans Administration, and the Public Health Service to work together to develop training programs that would produce clinical psychologists. These efforts led to the convening of the Boulder Conference on Graduate Education in Clinical Psychology in 1949 in Boulder, Colorado. The meeting launched doctoral training in psychology and gave us the scientist-practitioner model of training. Similar meetings also helped launch doctoral training programs in counseling and school psychology. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, alternatives to Boulder have been debated. In 1973, the Vail Conference on Professional Training in Psychology proposed the scholar-practitioner model and the Psy.D. degree (Doctor of Psychology). It is a training model that emphasizes clinical training and practice that has become more common (Cautin & Baker, in press).

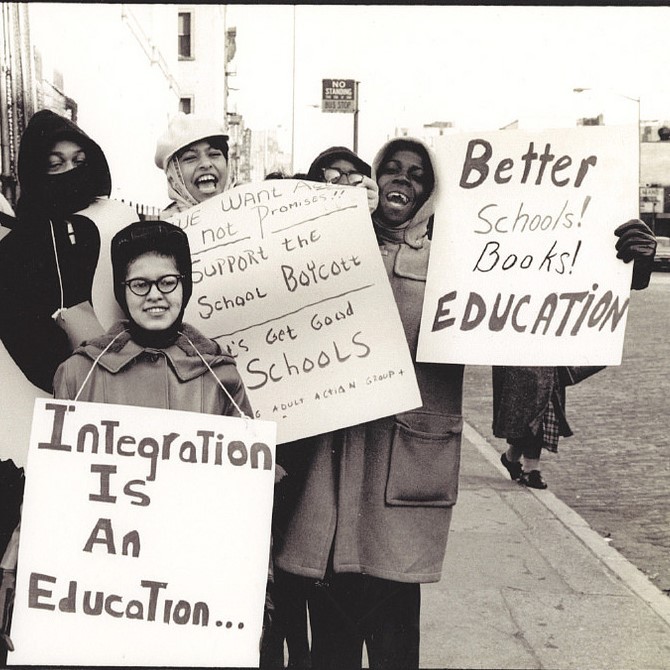

Psychology and Society

Given that psychology deals with the human condition, it is not surprising that psychologists would involve themselves in social issues. For more than a century, psychology and psychologists have been agents of social action and change. Using the methods and tools of science, psychologists have challenged assumptions, stereotypes, and stigma. Founded in 1936, the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) has supported research and action on a wide range of social issues. Individually, there have been many psychologists whose efforts have promoted social change. Helen Thompson Woolley (1874–1947) and Leta S. Hollingworth (1886–1939) were pioneers in research on the psychology of sex differences. Working in the early 20th century, when women’s rights were marginalized, Thompson examined the assumption that women were overemotional compared to men and found that emotion did not influence women’s decisions any more than it did men’s. Hollingworth found that menstruation did not negatively impact women’s cognitive or motor abilities. Such work combatted harmful stereotypes and showed that psychological research could contribute to social change (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987).

Among the first generation of African American psychologists, Mamie Phipps Clark (1917–1983) and her husband Kenneth Clark (1914–2005) studied the psychology of race and demonstrated the ways in which school segregation negatively impacted the self-esteem of African American children. Their research was influential in the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education,which ended school segregation (Guthrie, 2003). In psychology, greater advocacy for issues impacting the African American community were advanced by the creation of the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) in 1968.

In 1957, psychologist Evelyn Hooker (1907–1996) published the paper “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual,” reporting on her research that showed no significant differences in psychological adjustment between homosexual and heterosexual men. Her research helped to de-pathologize homosexuality and contributed to the decision by the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973 (Garnets & Kimmel, 2003).

Conclusions

The science of psychology is an exciting adventure. Whether you will become a scientific psychologist, an applied psychologist, or an educated person who knows about psychological research, this field can influence your life and provide fun, rewards, and understanding. My hope is that you learn a lot from the modules in this e-text, and also that you enjoy the experience! I love learning about psychology and neuroscience, and hope you will too!

Growth and expansion have been a constant in American psychology. In the latter part of the 20th century, areas such as social, developmental, and personality psychology made major contributions to our understanding of what it means to be human. Today neuroscience is enjoying tremendous interest and growth.

As mentioned at the beginning of the module, it is a challenge to cover all the history of psychology in such a short space. Errors of omission and commission are likely in such a selective review. The history of psychology helps to set a stage upon which the story of psychology can be told. This brief summary provides some glimpse into the depth and rich content offered by the history of psychology. The learning modules in the Noba psychology collection are all elaborations on the foundation created by our shared past. It is hoped that you will be able to see these connections and have a greater understanding and appreciation for both the unity and diversity of the field of psychology.

Timeline

1600s – Rise of empiricism emphasizing centrality of human observer in acquiring knowledge

1850s – Helmholz measures neural impulse / Psychophysics studied by Weber & Fechner

1859 – Publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species

1879 – Wundt opens lab for experimental psychology

1883 – First psychology lab opens in the United States

1887 – First American psychology journal is published: American Journal of Psychology

1890 – James publishes Principles of Psychology

1892 – APA established

1894 – Margaret Floy Washburn is first U.S. woman to earn Ph.D. in psychology

1904 – Founding of Titchener’s experimentalists

1905 – Mary Whiton Calkins is first woman president of APA

1909 – Freud’s only visit to the United States

1913 – John Watson calls for a psychology of behavior

1920 – Francis Cecil Sumner is first African American to earn Ph.D. in psychology

1921 – Margaret Floy Washburn is second woman president of APA

1930s – Creation and growth of the American Association for Applied Psychology (AAAP) / Gestalt psychology comes to America

1936- Founding of The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues

1940s – Behaviorism dominates American psychology

1946 – National Mental Health Act

1949 – Boulder Conference on Graduate Education in Clinical Psychology

1950s – Cognitive psychology gains popularity

1954 – Brown v. Board of Education

1957 – Evelyn Hooker publishes The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual

1968 – Founding of the Association of Black Psychologists

1973 – Psy.D. proposed at the Vail Conference on Professional Training in Psychology

1988 – Founding of the American Psychological Society (now known as the Association for Psychological Science)

Outside Resources

- Web: Science Heroes- A celebration of people who have made lifesaving discoveries.

- http://www.scienceheroes.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=258&Itemid=27

- Podcast: History of Psychology Podcast Series

- http://www.yorku.ca/christo/podcasts/

- Web: Advances in the History of Psychology

- http://ahp.apps01.yorku.ca/

- Web: Center for the History of Psychology

- http://www.uakron.edu/chp

- Web: Classics in the History of Psychology

- http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/

- Web: Psychology’s Feminist Voices

- http://www.feministvoices.com/

- Web: This Week in the History of Psychology

- http://www.yorku.ca/christo/podcasts/

Vocabulary

- Empirical methods

- Approaches to inquiry that are tied to actual measurement and observation.

- Ethics

- Professional guidelines that offer researchers a template for making decisions that protect research participants from potential harm and that help steer scientists away from conflicts of interest or other situations that might compromise the integrity of their research.

- Hypotheses

- A logical idea that can be tested.

- Systematic observation

- The careful observation of the natural world with the aim of better understanding it. Observations provide the basic data that allow scientists to track, tally, or otherwise organize information about the natural world.

- Theories

- Groups of closely related phenomena or observations.

- Behaviorism

- The study of behavior.

- Cognitive psychology

- The study of mental processes.

- Consciousness

- Awareness of ourselves and our environment.

- Empiricism

- The belief that knowledge comes from experience.

- Eugenics

- The practice of selective breeding to promote desired traits.

- Flashbulb memory

- A highly detailed and vivid memory of an emotionally significant event.

- Functionalism

- A school of American psychology that focused on the utility of consciousness.

- Gestalt psychology

- An attempt to study the unity of experience.

- Individual differences

- Ways in which people differ in terms of their behavior, emotion, cognition, and development.

- Introspection

- A method of focusing on internal processes.

- Neural impulse

- An electro-chemical signal that enables neurons to communicate.

- Practitioner-Scholar Model

- A model of training of professional psychologists that emphasizes clinical practice.

- Psychophysics

- Study of the relationships between physical stimuli and the perception of those stimuli.

- Realism

- A point of view that emphasizes the importance of the senses in providing knowledge of the external world.

- Scientist-practitioner model

- A model of training of professional psychologists that emphasizes the development of both research and clinical skills.

- Structuralism

- A school of American psychology that sought to describe the elements of conscious experience.

- Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon

- The inability to pull a word from memory even though there is the sensation that that word is available.

References

- Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31.

- Diener, E., & Crandall, R. (1978). Ethics in social and behavioral research. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Easterbrook, G. (2003). The progress paradox. New York, NY: Random House.

- Guzzo, R. A., Jette, R. D., & Katzell, R. A. (1985). The effects of psychologically based intervention programs on worker productivity: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 38, 275.291.

- Hoffman, S. G., & Smits, J. A. J. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 621–32.

- Lilienfeld, S. O. (2007). Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 53–70.

- Moore, D. (2003). Public lukewarm on animal rights. Gallup News Service, May 21. http://www.gallup.com/poll/8461/public-lukewarm-animal-rights.aspx

- Sales, B. D., & Folkman, S. (Eds.). (2000). Ethics in research with human participants. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Benjamin, L. T. (2007). A brief history of modern psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Benjamin, L. T. (2000). The psychology laboratory at the turn of the 20th century. American Psychologist, 55, 318–321.

- Benjamin, L. T., & Baker, D. B. (2004). From séance to science: A history of the profession of psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Cautin, R., & Baker, D. B. (in press). A history of education and training in professional psychology. In B. Johnson & N. Kaslow (Eds.), Oxford handbook of education and training in professional psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Evans, R. B. (1972). E. B. Titchener and his lost system. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 8, 168–180.

- Fancher, R. E. (1987). The intelligence men: Makers of the IQ controversy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Fancher, R. E., & Rutherford, A. (2011). Pioneers of psychology: A history (4th ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Fuchs, A. H. (2000). Contributions of American mental philosophers to psychology in the United States. History of Psychology, 3, 3–19.

- Garnets, L., & Kimmel, D. C. (2003). What a light it shed: The life of Evelyn Hooker. In L. Garnets & D. C. Kimmel (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on gay, lesbian, and bisexual experiences (2nd ed., pp. 31–49). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Goodwin, C. J. (2011). A history of modern psychology (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Goodwin, C. J. (1985). On the origins of Titchener’s experimentalists. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 21, 383–389.

- Guthrie, R. V. (2003). Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Leahey, T. H. (2012). A history of psychology: From antiquity to modernity (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Scarborough, E. & Furumoto, L. (1987). The untold lives: The first generation of American women psychologists. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Shultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2007). A history of modern psychology (9th ed.). Stanford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- Sokal, M. M. (1980). Science and James McKeen Cattell. Science, 209, 43–52.

- Titchener, E. B. (1909). A text-book of psychology. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Wertheimer, M. (1938). Gestalt theory. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of Gestalt psychology (1-11). New York, NY: Harcourt.

Authors

Edward Diener

Edward DienerEd Diener, Senior Scientist for the Gallup Organization and professor at the University of Virginia and University of Utah, received three of the highest honors in psychology (APA’s Distinguished Scientist Award, the APS William James Award, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences) for his groundbreaking research on happiness.

David B. Baker

David B. BakerDavid B. Baker is the Margaret Clark Morgan Executive Director of the Center for the History of Psychology and professor of psychology at the University of Akron. He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and the Association for Psychological Science. He teaches the history of psychology and does research and writing on the rise of professional psychology in America during the 20th century.

Heather Sperry

Heather SperryHeather A. Sperry, M.A. is currently a graduate student in the Counseling Psychology program at the University of Akron. She received her M.A. in Counseling Psychology from the University of Akron. Her research interests include multicultural and feminist issues.

Creative Commons License

Why Science? by Edward Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Why Science? by Edward Diener is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

History of Psychology by David B. Baker and Heather Sperry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

History of Psychology by David B. Baker and Heather Sperry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.