By Jennell Thomas / 15 November 2023

American advertising of the 1970s sparked a new era for the portrayal of African Americans. With the goal of expanding their consumer base, companies began moving away from the many negative historical depictions of African American subjects in advertisements for white audiences. One of the most profound launches into media diversification came with the McDonald’s “Get Down” ad campaign which featured images and language that were meant to be more representative of African Americans of the time. The advertisements relied heavily on a specific linguistic style to reach its targeted audience. While the “Get Down” campaign gave African-Americans a new sense of visibility in mainstream media, the reliance on stereotypes revealed the complexity of creating messages for specific ethnic groups.

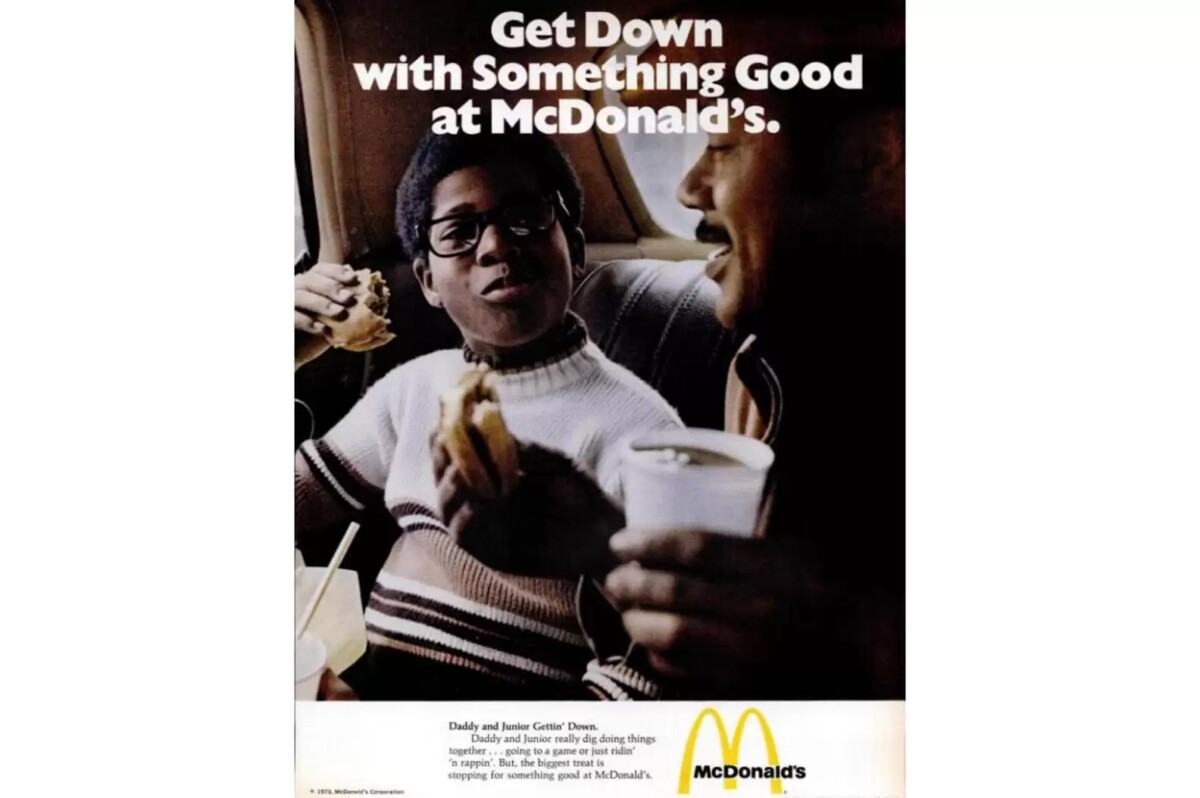

In advertising, consumers who see someone who looks like them using a product are more likely to purchase that product (Cruz). African-American graphic designers Tom Burrell and Emmett Mcbain, of the Burrell McBain Advertising agency, kept this in mind when creating magazine advertisements for the McDonald’s “Get Down” campaign (Cruz). One of the ads was featured in the February, 1973 issue of Ebony magazine, a magazine made specifically for a black audience (“About EBONY – EBONY”, “Emmett McBain: Pioneer in African American Advertising). The headline reads, “Get Down with Something Good at McDonald’s.”. The copy follows with, “Daddy and Junior Gettin’ Down”, “Daddy and Junior really dig doing things together…going to a game or just ridin’ ‘n rappin’. But, the biggest treat is stopping for something good at McDonald’s” (fig. 1). Both texts feature the use of vernacular that would be familiar to African American communities of the 70s. The phrase “Get Down” refers to a style of dancing that is energetic and free, symbolic of a good time (Wood). Telling the audience that having McDonald’s is a joyous occasion, an experience to be happy about. The copy sets the scene for the father-son duo on the advertisement and expands on the theme of enjoyment. Daddy and Junior “really dig” or really like spending time together (fig. 1). They ride around, “ridin”, rap to hip hop “rappin” and go to games. The copy drops the ‘g’ from words that end in -ing. While not specific to African American speech, it is often associated with casual conversation amongst African-Americans (Cran and Macneil). The final sentence and call to action declares that while the usual activities that the duo take part in are fun, they do not beat getting McDonald’s. The linguistic messages are further solidified by the imagery. The advertisement shows a photograph of Daddy and Junior sitting in the backseat of a car, having a burger and drink (fig.1). The relationship between the subjects is very normal: the son, with food in his mouth, looks over to his father who is in the middle of saying something. The son’s face is in full view while we only see the profile of the father’s face. The burgers are half eaten, they are actually enjoying the food. Junior’s cup is barely in frame and the father’s burger is out of focus, thus creating a very ‘typical’, natural scene. The imagery reflects the casualness that comes with getting fast food. It can be eaten anywhere, and for these two subjects, anyplace. For the targeted audience there’s an emphasis on reality which works well with a brand like McDonald’s.

Tom Burrell and his peers coined the term, “positive realism”, meaning to depict “black people in a positive, realistic light”, in juxtaposition to black culture (Jones 11:02). For the “Get Down” advertisement, the dominant reading was for a black audience to see themselves in an unpretentious and tangible way. Designers made the conscious decisions of choosing language and imagery that best represented a typical father and son outing. The linguistic message is strong, the specific vernacular used would start a dialogue with its audience. The image shows a favorable relationship between a black father and son, something that would help improve preconceived notions of black family units. The 70s set out to change perceptions of black communities as well as include them into mainstream consumerism (Bristor et al. #44). But what the designers of the 70s may not have been privy to was just how the intended positive attributes of the branding led to modern day oppositional readings of the ad. Mainstream media has the ability to reach a lot of people, and not all of them will get ‘it’, or agree. For instance in a response to The Atlantic, “Selling the Seventies” articles about advertising, many readers saw the ad as “lame and stereotypical” (Bodenner). Concerning the language, people who took the advertisement at face value would be under the impression that all African-Americans spoke that way (Bodenner). There has been a naturalization that African-American Vernacular English is not ‘proper’ American English. As it has been associated with being wrong, incomplete, or used by people who are not educated. While this is further from the truth, some audiences may choose not to look beyond the advertisement. Additionally, associating Daddy and Junior with riding around in the car listening and rapping along to hip hop music has the ability to create the idea of a one dimensional African-American. In hindsight, Emmett McBain and Tom Burrell sought to open the doors for a more positive depiction of African- Americans in the “Get Down”, the evolution of opinion has called for the re-examination of its meaning.

Being one of the first of its kind, the “Get Down” campaign set the precedent for inclusion in media. Media in the 1970s saw a shift, the black consumer base was no longer an afterthought. This was seen across both advertising and film. The “Get Down” advertisement relied on elements of language and culture, to develop an image for African-Americans. The goal was to deliver a message that was recognizable, relatable, and positive. However, the reliance on stereotypes has warped its meaning overtime. I have a more negotiated reading of the advertisement. The subject matter as it stands for the 1970s was extremely important, this cannot be denied. However, I can understand how the choice of vernacular used can be seen as excessive. Now more than ever, the social responsibility of designers is vital. We must stay educated on societal biases and acknowledge the role that we play in creating media for all.

Works Cited

“About EBONY – EBONY.” Ebony Magazine, Ebony, https://www.ebony.com/about-ebony/.

Bodenner, Chris. “When Do Multicultural Ads Become Offensive? Your Thoughts.” The Atlantic, 22 June 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/06/advertising-race-1970s-stereotypes-offensive/395624/.

Bristor, Julia M., et al. “Race and Ideologu: African-American Images in Television Advertising.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, vol. 14, no. 1, 1995, pp. 44-59, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30000378.

Burn, David. “Tom Burrell, Ad Legend.” Adpulp, 18 October 2021, https://adpulp.com/tom-burrell-ad-legend/.

Cran, William, and Robert Macneil. “Do You Speak American . For Educators . Curriculum . College . AAE.” PBS, MACNEIL/LEHRER PRODUCTIONS, 2005, https://www.pbs.org/speak/education/curriculum/college/aae/#aaepro.

Cruz, Lenika. “’Dinnertimin’ and ‘No Tipping’: How Advertisers Targeted Black Consumers in the 1970s.” The Atlantic, 7 June 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/06/casual-racism-and-greater-diversity-in-70s-advertising/394958/.

“Emmett McBain: Pioneer in African American Advertising.” The American Academy of Art, 15 February 2023, https://www.aaart.edu/emmett-mcbain/.

Jones, Robert. “Thomas Burrell Tent Talk.” YouTube, 1 April 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DRwmi1nEXU.

Mcbain, Emett. “Emmett McBain Afro-American Advertising Poster Collection | Collection: NMAH.AC.0192.” Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives, 1985, https://sova.si.edu/record/NMAH.AC.0192.

Wood, Peter H. “Great Performances: Free To Dance – Behind The Dance – Gimme De Knee Bone Bent.” THIRTEEN.org, THIRTEEN, https://www.thirteen.org/freetodance/behind/behind_gimme2.html.