My Teaching Philosophy

My teaching philosophy is rooted in the recognition that I am an experimentally-minded instructor whose greatest classroom joy comes from working directly with students on their own ideas across a range of modalities and media. The components of this philosophy were seeded through two graduate degrees focused on writing and working with writers (see here for an early statement of teaching philosophy) and were developed across my publications. In these works, you will see me building my philosophy of how to create an effective community of learners through the praxis of theoretical knowledge and empirical testing of these ideas in the classroom. Whether it be the absolutely imperative role of reflection in learning (link), or the importance of active learning through low-stakes activities (link), or how to scaffold metacognition through student research in the classroom (link; link), or the importance of recognizing the substantial differences between the intersectional identities of classroom participants and institutional assumptions about learners (link), I have used my early career to create a nexus of interrelated ideas centered around the record of what has worked in my own teaching practice.

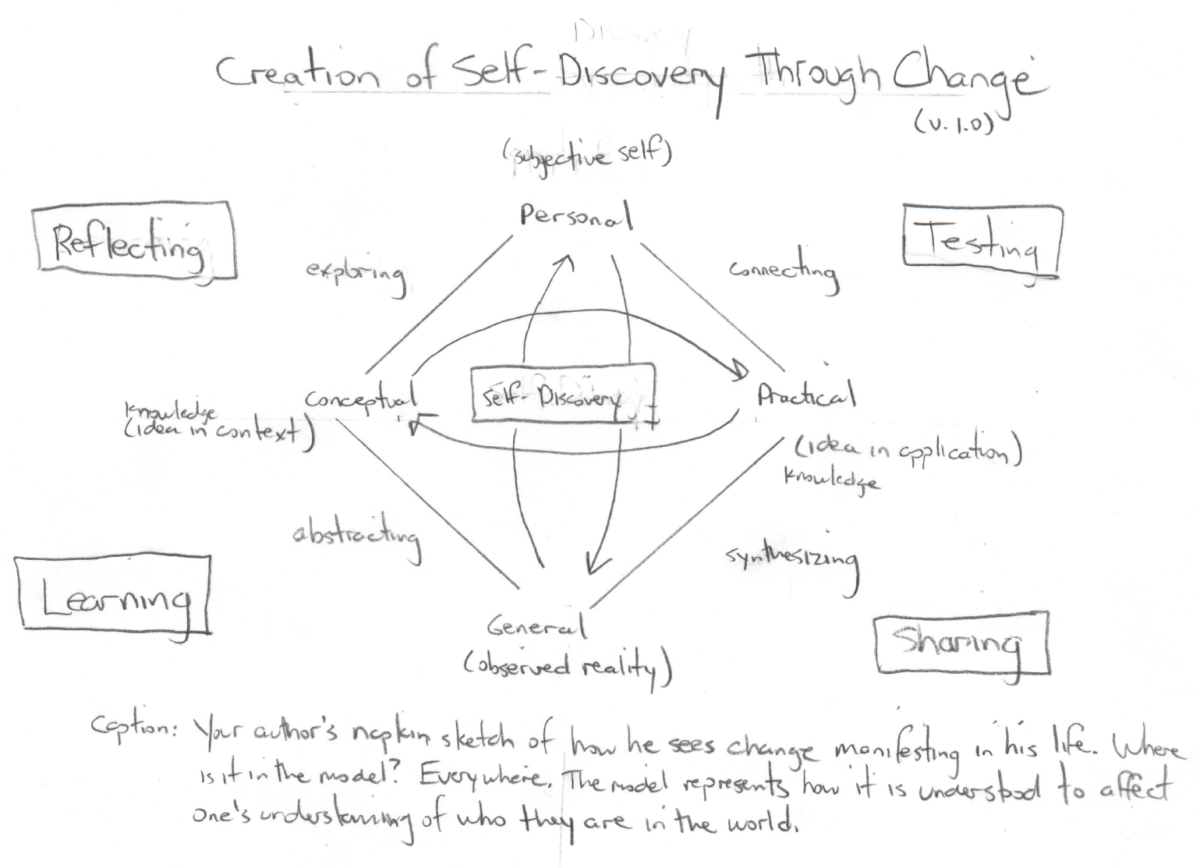

While publications are powerful touchstones corresponding to the instructor I was when I wrote them, and reflect how that past instructor informs the one I am now, my current teaching philosophy is the the product of the evolution of these ideas combined with the continuous refinement of my own understanding through learning new things, reflecting on what I have learned, testing my knowledge, and sharing the results. You can see a handy prototype graphic of this dynamic I’ve created below for a future publication.

At the root of my current philosophy is the relationship between learning and self-discovery through the growth that comes through failure. Many of my students have commented that my courses are object lessons in how to fail productively by taking well-measured risks, observing the results, and adapting their workflow to achieve better results.

I believe that learning is fundamentally enhanced by the experimental dynamic of productive failure among a diverse community of learners, and through the analysis of this failure and synthesis of new ways of thinking and doing as a result. At the core of my philosophy I believe that we learn because we hope to do, feel, believe, or see something new. The hope for new experience is the most powerful intrinsic motivation for learning I know, and my role in the classroom is to open this door for students and provide them with the necessary context that they may continue the journey whether it be in the next class or the next phase of their life.

My Theory of Pedagogy

The foundation of my teaching philosophy is to create a community tolerant of, and filled with opportunities to learn by, embracing the fundamental relationship between productive failure and self-discovery. I want students to apply this model of resiliency in their own life. My theory of pedagogy that has pushed me to arrive at this bold focus of optimizing students’ learning through controlled failure based on my application of the works on learning, skill acquisition, and optimization of Lurian-school psychologist, Lev Vygotsky, and positive psychologist theorist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. I employ the models of learning and creativity using theories and practices from the New London Group’s concept of multilitearcies and the design of social futures, coupled with socially transformative theories of pedagogy in literacy (Paulo Friere) performance (Augusto Boal), and play (Gonzolo Frasca). My influences on the drivers of youth identity formation (David Buckingham; Mimi Ito; Lisa Nakamura) and ideological positioning (James Gee; Colin Lankshear). Finally, within this framework, I’m deeply affected by the literacy and ethno-methods work of Jacqueline Jones Royster, Shirley Brice Heath, and Deborah Brandt.

While this may seem like a laundry list of critics, theorists, and practitioners, let me demonstrate how this theoretical underpinning influences my pedagogy in ENG 1101 – Introduction to College Composition and Communication. The traditional, if unwritten, view of this course is that it is an exercise in conformance to the expectations of genre, of format, and of evidence-supported reasoning. I hear this often from colleagues who complain this course “doesn’t teach students to write properly.” While I think “writing properly” is a reasonable outcome to interpret out of the experience of earning a college degree, it is not as relevant to the beginning of this process as a non-specialist would assume. Students arrive to our classrooms with a dysfunctional relationship between education, schooling, self-efficacy, and communication. Students see an untransversable barrier between the literacies they acquire outside of education and those demanded of them within school.

For many of our students, no amount of classroom-based instruction they encounter during their degrees will fully accomplish the communicative goals of an education because they don’t believe in the work. There is a subjectivity gap between who they believe they are and who the believe school asks them to be. I begin in a different place than the orthodoxy and correctness of “proper writing” and ask students to do a deep dive into the invention process with continuous low-stakes self-exploration through the written word. In the first month of my course, they write thousands of words without fear of judgement or failure. We treat writing as an act of developing and exercising voice to one’s own ends — a taking of ownership over writing, and in turn, taking ownership over the goals to which one applies their education. As we work, we treat the class as an experimental project where we use writing to continuously refine our understanding of ourselves, what we want out of the class, out of our schooling experience, how we will apply what we learn to impact the world, and the role that writing will play in that work. Rather than a conformance to orthodoxy, my students first experiences with writing in college are an epistemological exploration of knowledge, language, and self-discovery. They are learning to connect the tool (writing) to meaningful purpose (improving their lives and making the world a better place).

My Method of Pedagogy

All of my courses are inquiry-based, student-centered, inclusive and flexible, but demanding. To maintain a culture of openness and engagement that leads to learning, I only use quizzes and tests in one course, ENG 1161 – Language and Thinking. In that course alone I have found that a studied background in socio-linguistic concepts and terminology is necessary preparation for the experiential activities of the course, which involve data collection and analysis. In my other courses, we engage in dialectical learning through writing and discussion. The course content that students are tasked with learning become the material we work with through various forms, methods, and genres of text in different media and modalities. In ENG 1101, students do primarily personal writing, while in ENG 2400 – Films From Literature, the majority of writing students do for the course is in the form of visual essay and presentations and in the technically-oriented ENG 1133, ENG 2570, ENG 2575, and ENG 2700 courses – students engage in the process of iterative ideation and design-thinking culminating in projects presented as carefully designed documents written through an introduction to professional, not academic, workflows.

In each course, a deep and sustained reflection through writing is a key feature. This is work we all engage in, including myself, through the use of formative and summative 360-assessments of both students and my own performance. I survey students extensively at the beginning of the course through instruments I have developed over the years that provide me with robust data on who my students are as an audience of learners, as people who have come to education with particular goals and experiences, their preparation for the subject material, and their expectations for the course. I often have students begin classes with free-writing on new or traditionally problematic aspects of course content, my delivery, or their perception of their own progress in the course. All of these materials amount to hundreds of pages of data per course per semester. While one initially think this feels wasteful, the overwhelming response from students is that this experience is integral to the benefit they derive from my courses. Out of this surveying (mostly in the form of paragraph-sized answers), they think extensively about their interests, their educational goals and the challenges of achieving them, and begin the work of inventing a new subjective sense of who they are that aligns with the concepts and intellectual tenor of the course material. In short, the sustained focus on reflection allows students to continuously position and re-position themselves as learners in my courses, and each time presents an opportunity for perspective development and growth.

My Ethics of Pedagogy

An ethical focus has always guided my work with students. As a writing professor, one tends to live a bit more in the heads of students than in other subject areas. Students often disclose personal details in their writing that they would not in other otherwise, and if they need help, I am often a person to which they turn. Part of my teaching philosophy and practice is to always be unambiguous with students about the role I play in their lives. In each of my syllabi, I include a section on instructor responsibilities, which are a set of guarantees that I offer students about their interactions with me. Of course, these are shaped by the institutional nature and policies governing the instructional environment, but those are simply a baseline from which we negotiate the mutual expectations we hold for each other in the class.

I approach this practice from what can be referred to as a “pedagogy of charity” opposed to a “pedagogy of severity.” I recognize that the classroom often serves as a “contact zone” where assimilation to dominant cultural norms is expected to occur, and yet this form of colonization can be damaging to students’ existing sense of identity, family, and community. A pedagogy of charity allows students the ability to engage in transculturation, where they are able to retain their existing language features and identities, while engaging in the dialectical act of both assimilating features of education into their lives, while responding to those in critical ways. The goal of the ethical stance I take in my instruction is that the goals of the classroom learning environment, and my instruction, be overtly focused on both students’ learning needs, and how students perceive the role and value of their education in their lives. Their willingness to seriously consider the efficacy they wield in their own learning, and the agency to is resultant from dedication to the tasks I have set before them, depends on the covenant created between the students and myself through the realization of these ethics.