A “Design Thinking” Framework

I continuously recreate my courses through the iterative design process of data gathering, incremental change through assessment, and experimenting with change through the outcome of this process. Each time I deliver a course, it is designed directly out of the experiences and feedback from previous cohorts of students. This model of pedagogical change closely aligns with the problem-solving process popularly known as “design thinking.” The value of a design thinking approach to my own course design is that it provides a human-centered and data-informed method for prototyping and then implementing change with a “continuous improvement” ethic. More broadly, design thinking is a set of concepts and methods is used broadly to respond to persistent human problems that require innovation as well as expertise to address. Design thinking is used widely for organizational change and planning, product and service development, and systems implementation.

I have always approached the courses I teach with a focus on the experience of the course and how to improve that experience. When I wrote my master’s thesis on the impact of the “quality movement” on assessing writing, I saw my work as an act of resistance to the top-down enforcement of assessment standards. What I didn’t anticipate was just how deeply my own teaching practice would come to be influenced by self-adopted management philosophy and tools. While I refuse to see my students as consumers, or the classroom as a corporatized or transactional space, as a writing professor who teaches in a technical environment, I see myself as very much asking my students to do “work” that contributes to developing our learning community. To me, this means that I must conduct myself with the same degree of ethical responsibility that I would expect myself from someone who was responsible for directing my own work.

What this has come to look like is that I have slowly transformed the way I teach writing from a process-based pedagogy focused on producing effective texts to a course based on the role of iterative design in the creation of effective writing and learning. While I still teach a process-based course, the process itself is not procedural in that it is not focused on orthodoxy or correctness. It is conceptual and experimental. I have arrived at this point by treating my own courses in exactly the same way, as conceptual, experimental, and contingent on the results. Over the years, that has meant moving away from being student-centered toward student-empowered. For every student, I gather a great deal of linguistic, cultural, and educational background information that I pair with in-depth questions relevant to the particular courses’ content. Rather than finding this invasive, students feel recognized and acknowledged. I no longer rely on SET scores or ad hoc feedback from students to gauge my effectiveness. I engage in continuous 360-degree written assessment, where students and I both evaluate each other on an ongoing basis. If a student tells me that something isn’t working for them.

My goal for each course, beyond meeting the basic course outcomes, is to provide each student with an experience that is tangibly meaningful beyond the course itself. Since 2018, I have done this by beginning to incorporate design thinking principles and methods directly into the curriculum of my process-based writing courses. I lead students through the experience of iterating an idea they develop themselves into a concrete plan for future work that is informed by the disciplinary content of the course. This change-based approach has transformed my project-oriented courses, like ENG 2575 – Technical Writing, into entrepreneurial hotbeds where students feel as if they are not only actualizing their own interests, but also their own sense of who they are and what they are capable of as they pursue their projects. Many of these students keep in touch with me over the years as they move into their professional lives where they report learning this process in my course(s) is foundational to their workplace success.

Beginning with Empathy

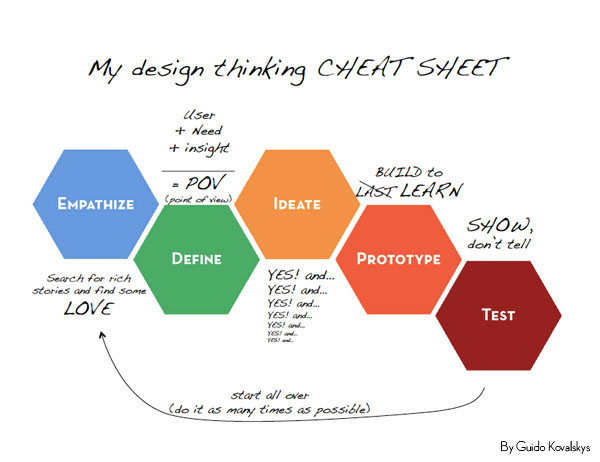

The essentialized process of design thinking as described by Stanford University’s d.school is well-represented in Guido Kovalskys’ (2013) blog post on The Whiteboard, which is the d.school student community website:

The design thinking pentad is above (with Kovalskys’ annotations) consists of the following qualities: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. Empathy is a quality that does not come naturally to me. Admittedly, I must practice it and do so mindfully to keep it at the forefront of my teaching practice. Yet, empathy is a core principle of design thinking and it is fundamental to making a human-centered design approach effective.

The most effective way I have to cultivate empathy for my students is to learn about them as people. To do so, I begin my writing courses with a significant amount of inventorying (i.e., inventio). Beyond a traditional search for arguments, as inventio is typically considered to be, I consider it in the same vein as Mary Carruthers in her powerful historiographic treatment of inventio in The Craft of Thought (1998) as a process related to “gathering up” and “drawing in” of resources for all semiotic, logical, and creative domains. The inventorying exercises I have designed allow students to create the materials that will be used to seed future writing work. At the same time, I use them myself to search for common and uncommon ground on which to build a foundation of mutual warmth and respect to develop a community of learners.

Defining the Work

I find my writing students come to my class expecting to be able to succeed by filling out content worksheets or completing formulaic work predicated by a step-by-step guide on how to do so. These students lament how open-ended my assignments are. This is not to say that my assignments are ill-defined. They are highly structured, but they are done so in a way that requires students to learn how to construct a project workflow by making consequential choices about how to direct their attention and focus. For example, in an essay-based course, I would never assign an essay topic to a student. Instead, I assign a process (including consulting with me) for discovering a meaningful topic through creative application of writing and design principles. Next, I assign a process for encouraging the growth of their understanding of the topic, and change in perspective through topical research and reflective writing. These processes involve providing students with the background, rationales, relevant readings, working methods, and deliverables that track their progress. The key difference, however, is not the primacy of the outcome, or even adherence to the process.

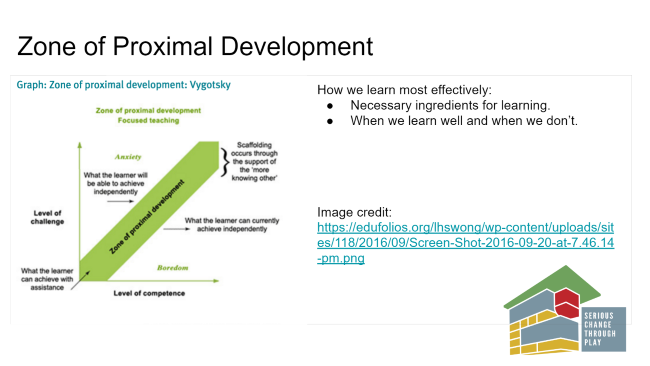

What I am looking for from my students for them to begin developing a mindset for learning and thinking that writing can support. To “define the work,” I lead students through an adaptation of the failure cycle of creative discovery articulated by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (the founder of “flow theory”) in his study of optimal performance, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. In his study of world-class talent in the domains of science, the arts, and business, Csikszentmihalyi found that four primary activities promoted long-term success: a productive relationship with failure, joining or creating a community of peers, introspection and procrastination at optimal moments, and the ability to iterate effectively on a difficult problem. The assignment sequences I design for students are intended to push them to the point of failure (hence their frustration) and then guide them through this within a Vygotskyian zone of proximal development to success through sharing their efforts, reflecting on them, and choosing an appropriately constrained iteration to test.

A Zone of Proximal Development graph I use in ENG 1101 to help explain to students my approach to course design.

Ideation through Inquiry

Creating a generative ideation process is a challenge even for sophisticated practitioners. We are constantly faced with the question of “what now?” as we progress towards a complex goal. Even when a process is clearly defined, or we are experienced with the methodology of practice, unexpected circumstances and results can throw our work product or our approach to it into question. This is doubly true for students, who are defined in part by their lack of experience. Coming up with good ideas requires a great deal of attention and focus, not just on the topic at hand, but to the conditions in which we work, who we include in the process, how we define the work, how we organize it, and what goals we set on the path of progress. One of the features of a sophisticated practitioner is an ability to work through these issues with some degree of automaticity. For a student, they become an object of inquiry themselves as the student learns how to create a productive context within which to work and what decisions go into doing so.

I often tell my students that my courses are not designed to teach them how to write the best text. Instead, we focus on how to ask the best questions to understand the problem we are facing and practice writing in a way that helps us make progress on this problem. What constitutes the best text is entirely dependent on the context, situation, and resources available. In typical schooling situations, those problems are already solved for students. In my courses, they become part of the program of study. As a result, my students must learn to ideate across the full framework of a problem, from defining the problem itself, through designing possible solutions (text-based or otherwise) and thinking about how they will prototype and test these . We do this in the spirit of inquiry, where learning to ask the right questions and what to do with the responses are critical tasks. Oftentimes, I ask students to do their ideation work combining more traditional writing methods and non-linear tools like the story canvas or simple heuristic diagrams.

Prototyping and Testing

In a 15-week writing class, we do not focus on solving big problems. Instead, I design my own courses to show students how to recognize a big problem that is meaningful to them and set to work on solving it. The projects that we engage, and the work product that results, tends to be preliminary in nature and contingent on students’ existing set of skills. Still, I am often amazed at how conceptually rich the prototypes that students’ deliver are. Whether these prototypes are proposal drafts, storyboards, visual essays, or something else entirely (like a LEGO model), they are entirely something that the student was not prepared to create when they entered the classroom. Even in introductory courses where students’ are not yet prepared to tackle tangible problems (e.g., seeking funding for an entrepreneurial idea), I encourage them to create a prototype that doesn’t solve a problem, but that they learn something important from the process and that they can test against what they didn’t know or could not do before.

I encourage students to think of their work as an ongoing process that stretches far beyond my course, or their college education. I remind students that they are practicing a set of conceptual and analytical skills that they can use along with their writing to make progress on any problem of their own choosing. I tell students that if they are able to complete one iteration of the design thinking process, they can complete it again and they can do so at their own direction. The result of this is a writing course that is no longer framed around writing in a particular genre to a schooling-defined standard that may or may not be applicable in their future work. Instead, students of my writing courses learn to integrate their writing into conceptual processes and a framework of discovery that is flexible, powerful, and immediate to their evolving needs as thinkers and doers in the world.