Note: A lot of the below content may be new to you; don’t worry! We’ll continue to review and discuss throughout our meetings, with additional activities and assignments.

Copyright

Copyright is a form of protection granted by U.S. law to the creators of “original works of authorship” including scholarly and creative works. Creators do not have to register their work or attach a copyright notice in order for their copyright protection to apply to the work; the protection exists automatically from the time the work is created.

“Rights” protected under U.S. Copyright Law

Copyright holders have exclusive rights to:

- Reproduce their work

- Prepare derivative works

- Distribute copies of their work

- Perform their work publicly

- Display their work publicly

What does copyright not protect?

Copyright does not protect facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed. Check out some scenarios to clarify your understanding of what can be copyright protected and what can’t.

Limitations to copyright Holders

Copyright law impacts information production and dissemination. Since creators automatically retain five exclusive rights as copyright holders, the law limits how a work can be used and distributed. This can make it challenging to integrate intellectual materials into educational settings.

There are a couple limitations to exclusive copyrights worth mentioning, especially in an educational context.

Fair Use

Fair use is a limitation on the exclusive rights of a copyright holder. If a proposed use meets the “fair use” criteria, and the user hasn’t agreed to abide by other terms—such as through a license agreement or a website’s terms of use—a copyrighted work may be used (in our case, sharer with students) without permission from the copyright holder.

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

-

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

Considering a proposed “fair use”

You don’t have to be a copyright expert to determine if the use of copyrighted material is “fair.” Evaluations of fair use must include a consideration of these four factors:

- Purpose and character of the use

- Nature of the original work

- Amount and substantiality of portion used

- Effect on the potential marketplace

Analyze whether the use you have in mind is fair using this tool.

The Teach Act

The TEACH Act of 2002, expanded the scope of online educators’ rights to perform and display works and to make copies integral to such performances and displays, making the rights closer to those we have in face-to-face teaching.

But there is still a considerable gap between what the statute authorizes for face-to-face teaching and for online education. For example, an educator may show or perform any work related to the curriculum, regardless of the medium, face-to-face in the classroom. There are no limits and no permissions required. Under 110(2), however, the same educator would have to pare down some of those materials to show them to online students. The audiovisual works and dramatic musical works may only be shown as clips — “reasonable and limited portions”.

Fair Use vs. the Teach Act

Some educators have concluded that it’s more trouble than it’s worth to rely on the Teach Act. This statute’s complexity provides a new context within which to think about fair use: the four factor fair use test seems simple and elegant. Even if we rely on and find 110(2) helpful, fair use will still figure heavily in our exercise of performance rights because putting anything online requires making a copy of it.

Fair use also remains important because the in-classroom activities the TEACH Act authorizes (even if the classroom is virtual) are a small subset of the uses of online resources educators may wish to make. It only covers in class performances and displays, not, for example, supplemental online reading, viewing, or listening materials. For those activities, as well as many others, we’ll need to continue to rely on fair use.

Section 110’s role in the balance of interests has always been to permit educators to share works with their students and to show others’ works in class. However, Section 110(2) significantly limits who may display and perform materials and under what circumstances, including how much they may use. The TEACH Act checklist, summarizes the 22 (!) prerequisites.

Fair Use and OER

The context of OER is significantly different from other kinds of educational uses where materials are only distributed to a small selection of students (think photocopies in a classroom or an article you upload to a site that requires a login like Blackboard). Since OER are meant to be freely shared with students and other educators in and outside of City Tech, this changes the purpose and character of use significantly.

Instead of thinking about OER contexts as similar to other classroom contexts, for the purposes of copyright it might be more helpful to think about OER as similar to materials that you might integrate into your own published scholarship. For example, if you were including data or an image from another sources in an article, you would need to potentially obtain permission as well as attribute the original source.

While Fair Use and the Teach Act will not directly pertain to your course redesign, they are important to be informed about, especially for future course development.

Creative Commons licenses

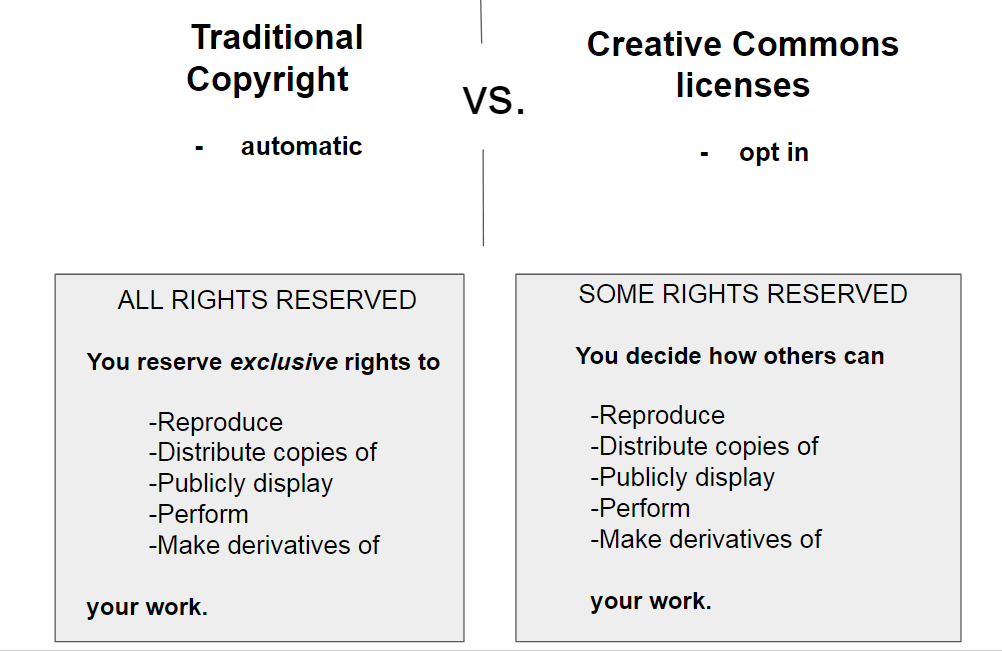

Since copyright is automatic whether a work has been published or not, the five exclusive rights that authors are entitled to under copyright, especially the ability to redistribute copies, impacts how a work can be used and distributed. Creative Commons licensing was developed as an intermediate between the traditional “All Rights Reserved” copyright and public domain works, which are not copyright protected at all.

So when did Creative Commons come onto the scene? The Creative Commons organization was founded in 2001 by legal scholars, artists, and activists to develop a legal framework that runs parallel to U.S. copyright law so that authors of creative and intellectual materials can retain their copyright, and decide how others use their work. They wanted to find some middle ground between the restrictions of traditional copyright and the ‘free wheeling’ public domain. This ethos is related to the free culture movement, the open source software movement, and the open access movement in scholarly publishing.

Read about the three layers (legal code, human readable, machine readable) of licenses on the Creative Commons website.

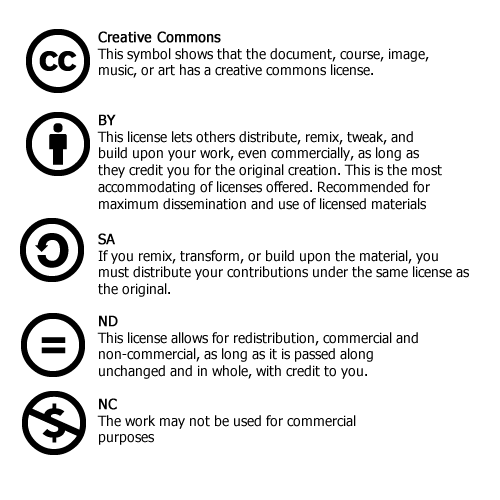

The image below shows the 5 icons that represent different components of CC licenses.

Credits:

Portions from the fair use section are adapted from the OER Copyright and Fair Use Module by Nora Almeida, licensed under a Creative Commons (CC BY) Attribution. Portions from the Teach Act sections are adapted from the Teach Act from University of Texas Libraries, licensed under a Creative Commons NonCommerical (CC BY-NC 2.0) Attribution.

Print this page