The article’s title is “When You Hear the Margin of Error Is Plus or Minus 3 Percent, Think 7 Instead,” by DAVID ROTHSCHILD and SHARAD GOEL. This article is about that the common knowledge for the people who follow election polling (human research survey of public opinion from a particular sample) is that there is plus or minus three percentage points of margin of error when 1000 people are surveyed. This ±3% is coming from the following formula that is found in statistics textbooks; percentage points = 1/square-root(sample size).

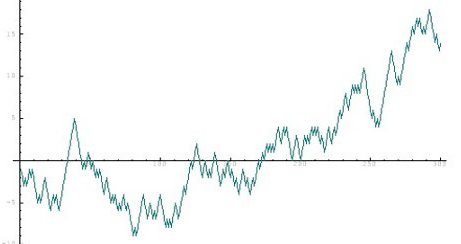

But the real margin of error –based on the history of campaign polls- is actually about six to seven percentage points; 4221 late-campaign polling averages (the result of synthesizing combined information, from many different polls that deal with the same issue, into a new set of numbers) were examined; “608 state-level presidential, Senate and governor’s races between 1998 and 2004.” The following graphs show “how the Republican candidate performed in races since 1998, compared with the average of all polls conducted in the final three weeks of the campaign.”

In other words, the results of these polling averages are just assumptions that are not accurate and can be reversed in any time as the elections progress. This is due to the errors that cause the big gap between both margins of error (±3% and ±7%), the 3% error covers the non-perfect representation of the full population even when the participants in the survey are selected randomly. But it doesn’t cover other errors such as frame error, nonresponse error, and the error in the analysis phase. These errors show up in two ways, one is that the variation between the polls is bigger than what’s in textbooks, second is that polls tend to overestimate or underestimate the true value.

The graphs above are used in this article as a reference to compare the average of all polls and the final election outcome which appear to be different. In other words, the margin of error of 3% is not correct; if the sampling variation was the only error, then the difference between the polling average and the election outcome would be smaller. Based on standard theory, averaging many polls will shrink this difference, but in reality, the difference persists in 2% and that is due to the similar assumptions made by survey organizations about who will vote.

In conclusion, the polls are just estimations about who will win the campaign, which are projected to changes any time before the election day, but only the election day will reveal either Mrs. Clinton or Mr. Trump for a president.

Reference: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/06/upshot/when-you-hear-the-margin-of-error-is-plus-or-minus-3-percent-think-7-instead.html?_r=0